“Someone once suggested that the black man pull himself up by his bootstraps.”

“The black man agreed that it was a good idea, but he wasn’t exactly sure of how to go about it. First of all, he had no boots, and secondly, he considered himself lucky to be wearing shoes.”

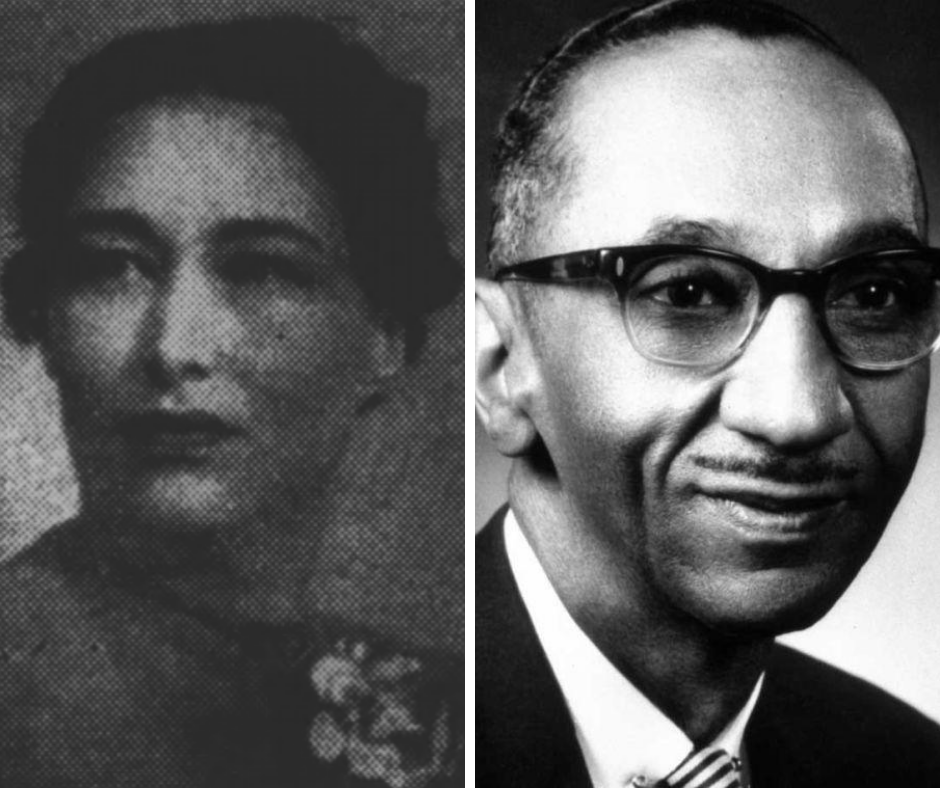

Andrew “Bo” Foster perhaps related to the figurative Black man described by Skip Hess in his 1968 Indianapolis News article.[1] Foster’s adolescence was marked by hardship and instability. Despite this, he became a prominent entrepreneur and civic leader in Indianapolis. Not only did he manage to procure “boots,” but went on to ensure that others in the community had a pair. In doing so, he created opportunities for socioeconomic advancement.

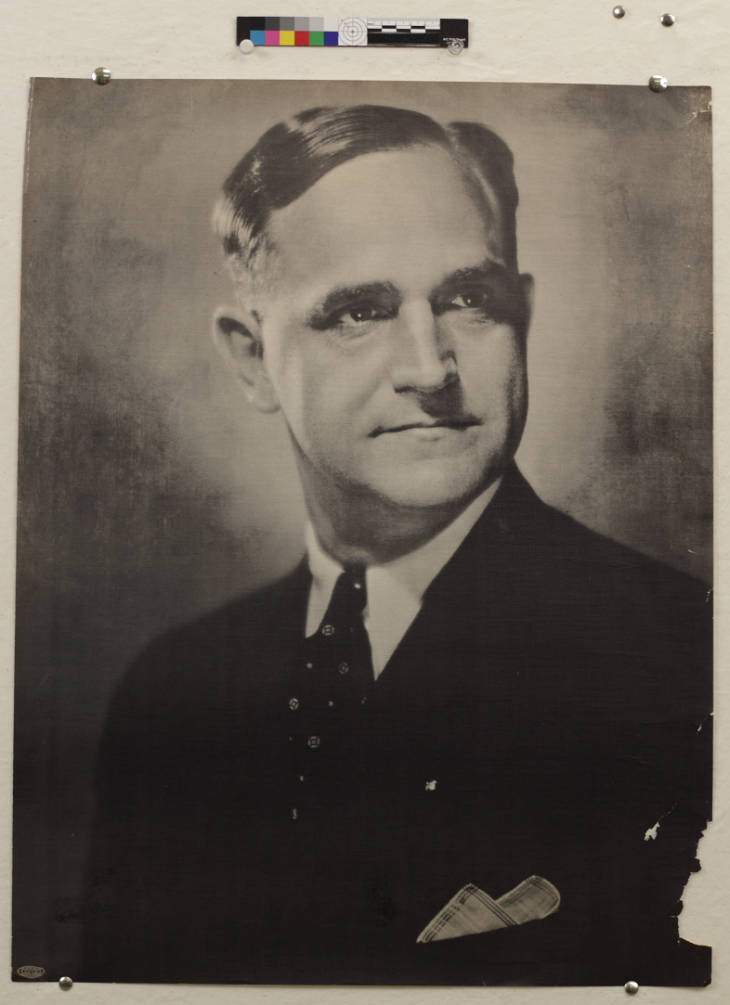

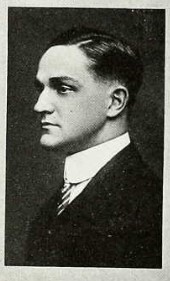

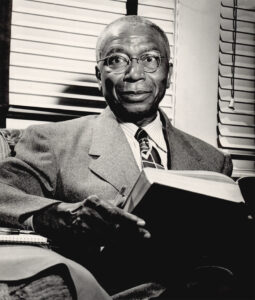

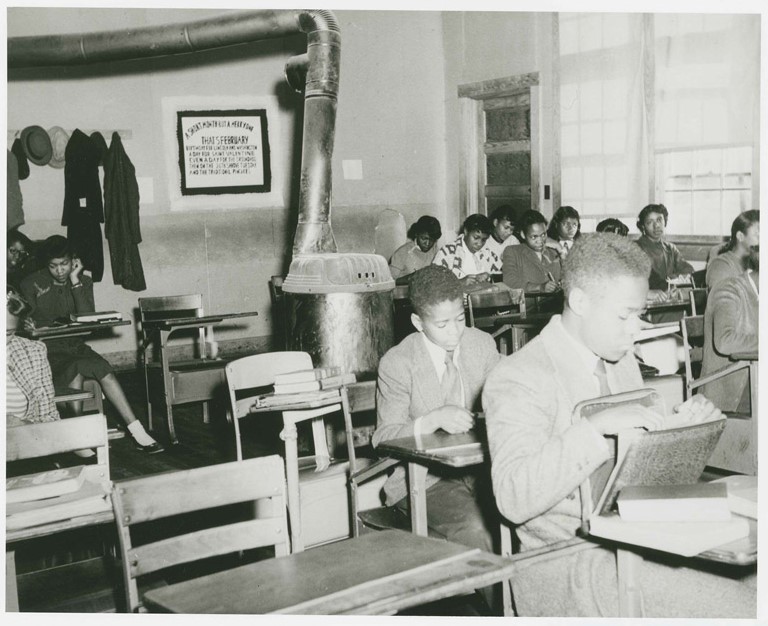

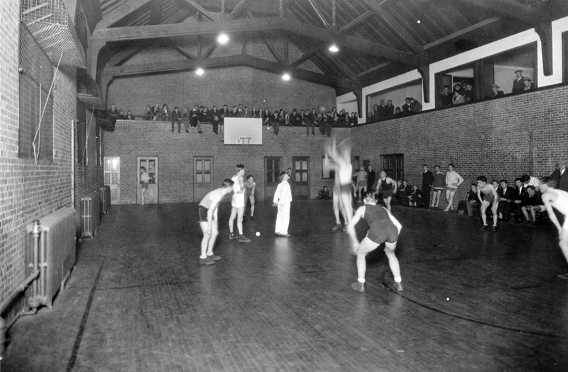

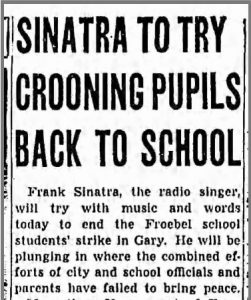

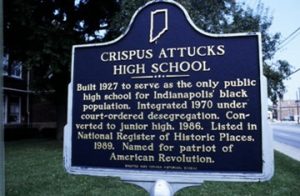

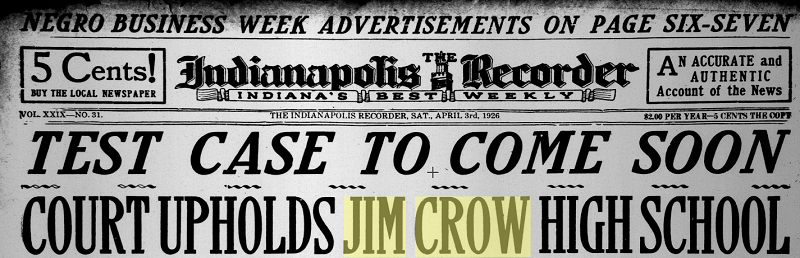

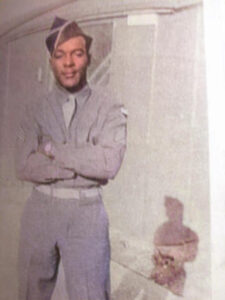

According to his grandson, Charles Foster Jolivette, Foster was born along an alley near Riley Towers in 1919.[2] His father, Edward, died when Foster was a young child. For reasons that are unclear, he was not raised primarily by his mother, Eva. When not staying with father figure William W. Hyde, a local Black attorney, he spent his childhood in the Indianapolis Asylum for Friendless Colored Children, which had a history of corporal punishment and unsanitary conditions.[3] Nevertheless, Foster kept up with his education, graduating from Crispus Attucks High School in 1938.[4]

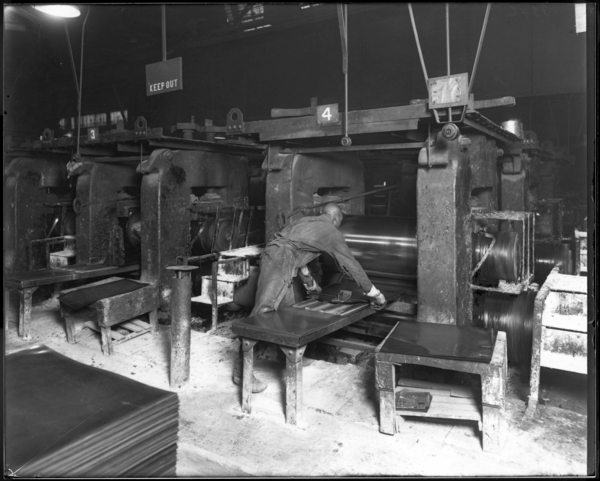

The Indianapolis News reported that after graduation he “hauled scrap iron on a tonnage basis.”[5] Shortly before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Foster was sent to Camp Wolters, an infantry replacement training center in Texas.[6] By 1943, he had graduated as a second lieutenant from officer candidate school at Camp Hood and went on to serve on a tank destroyer unit.

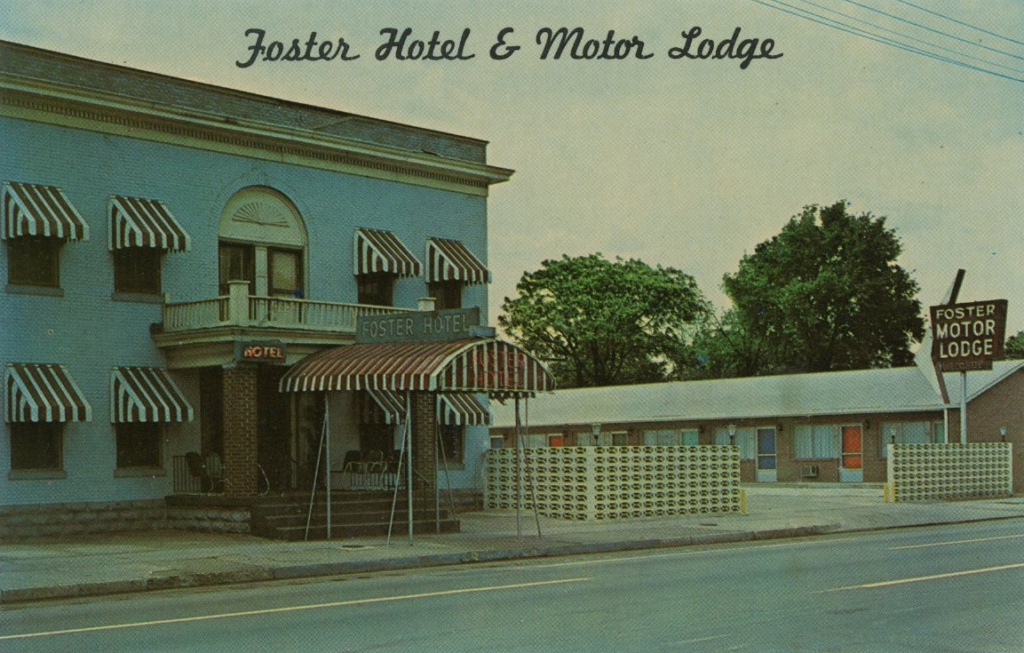

After Foster’s service, he established a lucrative Indianapolis trucking company, enabling him to open and manage several businesses that served Black patrons in the segregated city.[7] His work ethic was second to none, as he worked most holidays, and reportedly said “You must be willing to work 26 hours a day if you want to be in business.”[8] Reflecting on his prolific career in 1983, Foster told the Indianapolis Recorder that he had no formal training, “just high school, the Army and common sense. I came out of the Army and started hauling trash. I saw a need for a black hotel, then added a motel three years later in order to survive.”[9]

By 1949, he opened Foster Hotel and the Guest House at North Illinois Street.[10] Both were listed in The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, which published the names of safe, welcoming businesses and accommodations across the country.[11] At a time when Black Americans were turned away from hotels, Foster’s were one of the only in Indianapolis to serve them. In addition to Foster Hotel and Guest House, he opened the Manor House, Motor Lodge, Carrollton Hotel, and private rooming houses.[12] These businesses accommodated tourists, “permanent guests,” and famed customers, such as Muhammad Ali, LaWanda Page, Lionel Hampton, Nat King Cole, and Redd Foxx.[13] Unless these celebrities had friends or family in the city, they all stayed at a Foster establishment.

Patrons praised the facilities for their cleanliness, modern features, and hospitable staff. Foster opted against “frills” because “Negroes travel on a pretty tight budget” and he chose not to build a pool because of the liability insurance fees.[14] The Recorder attributed his “steady rise in the scale of fortune” to his “integrity, foresight, business acumen and high sense of fair play in his dealing with others.”[15] His bachelor pad reflected this burgeoning fortune. According to a 1954 Jet magazine profile, it was outfitted with “walls of black glass, a full-mirrored ceiling, monogrammed glass-enclosed tub and shower, and double lavatories in pink. The floor is pink and black marble and Foster had a lifelike nude painted on one wall.”[16]

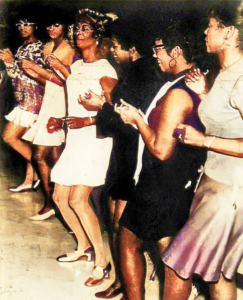

In addition to financial success, Foster founded his businesses to meet the need for a communal space in which to socialize, politically organize, and host civic and philanthropic events. According to the Recorder, Foster “saw blacks holding meetings at white-owned establishments ‘where they couldn’t always speak their peace’” and sought to provide a venue where they could.[17] Pearl’s Lounge, opened by 1970, did just that. Named for his wife, whom he married in 1962, the cocktail lounge at 118 West McLean Place (adjoining Foster Hotel). Foster later told the Recorder, “‘Many a black group has gotten its start here.”[18]

The Recorder considered the new addition “just about the most beautiful eating and drinking emporium in the Hoosier capital,” praising its “dim lighted lovers’ rooms of oriental design” and “beautiful mahogany bar with electronic stereo component for continuous music.” In a word, Pearl’s was “fantabulous.”[19]

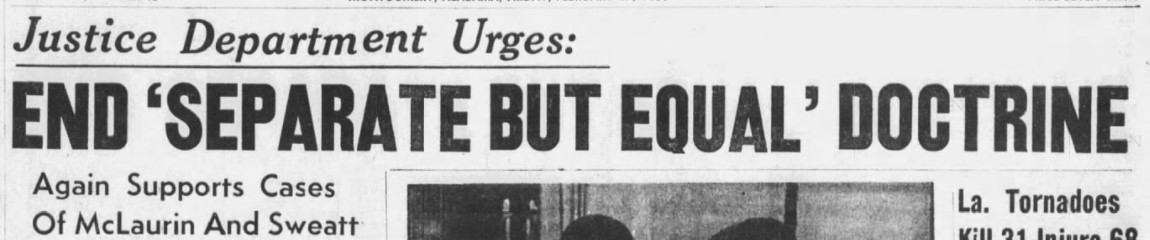

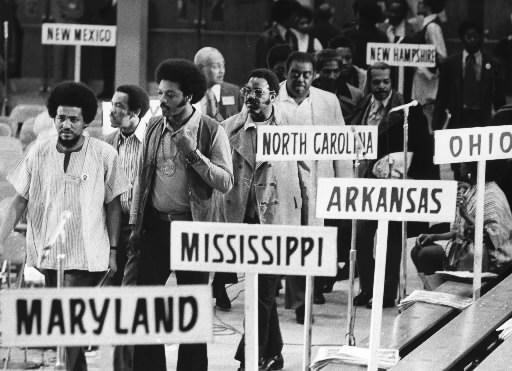

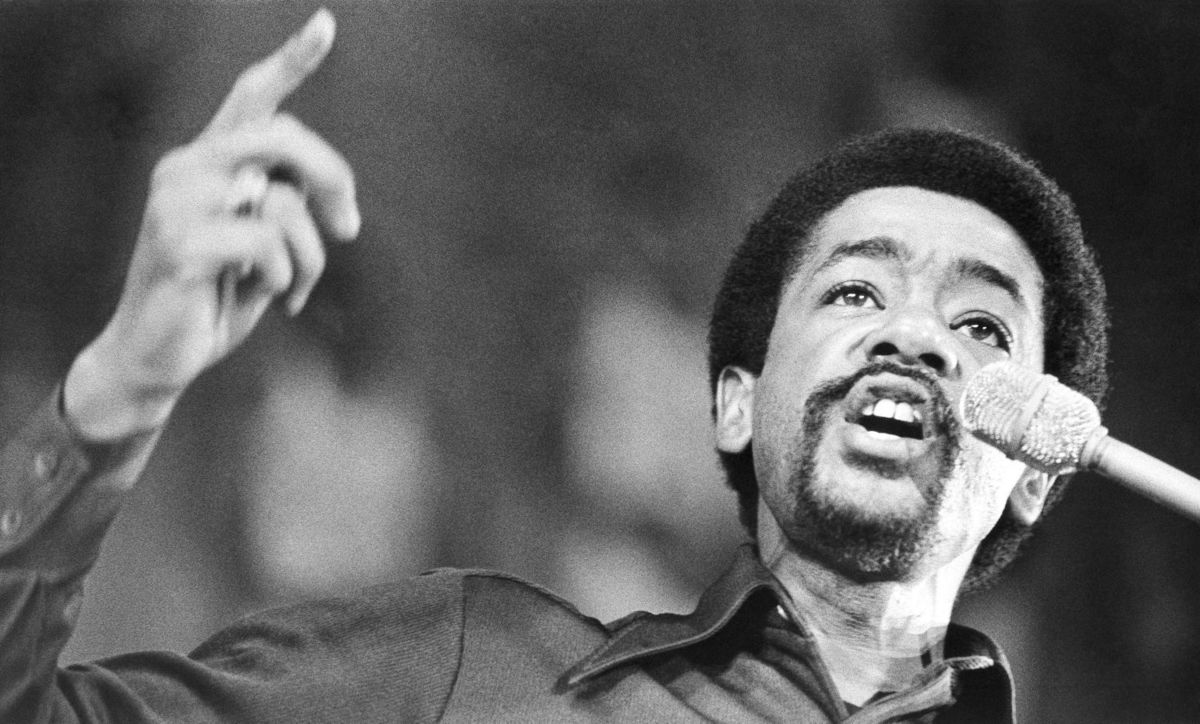

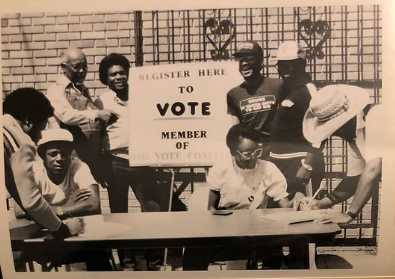

Pearl’s banquet hall and ballroom facilitated numerous events. These included a fashion show, voter registration program, and IU alumni meeting regarding how to best serve Black students. Pearl’s also hosted numerous NAACP events, including a businessmen’s luncheon, at which executive director Roy Wilkins spoke in favor of busing as a means to educational equality.[20] Pearl’s also served as a venue for furthering race relations. For example, the Recorder reported in 1975, “In their first major attempt to acquaint the owners, coaches and players with the black community, the Indiana Pacers will host a reception and a buffet dinner” at the lounge.[21]

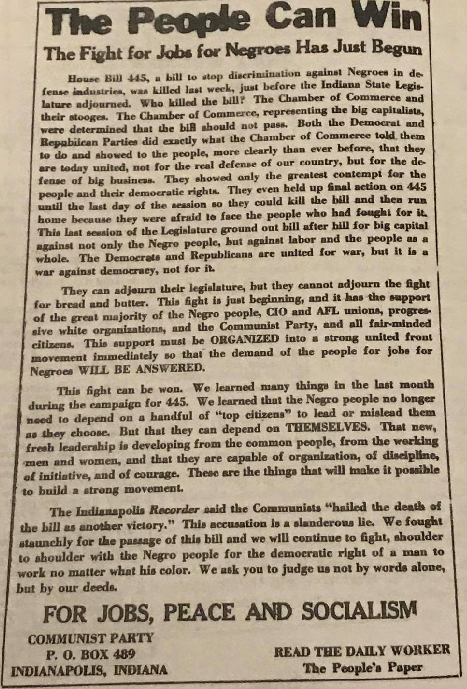

Pearl’s lounge hosted numerous political campaign events and debates—including those of Mayor William Hudnut, Judge Rufus C. Kuykendall, Senator Julia Carson, and Senator Richard Lugar.[22] It accommodated events for groups across the political spectrum, including Indiana Black Republican Council meetings and a Socialist Workers Party rally.[23]

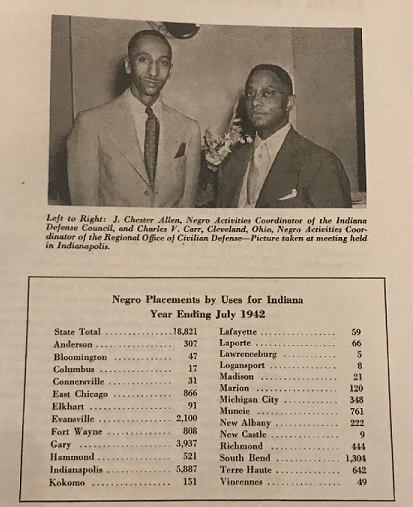

Foster not only uplifted the community through his businesses, but also as president of the Indianapolis chapter of the National Business League (NBL) in the 1960s and 70s. Through the NBL—described as the “chamber of commerce of Negro enterprise” and a “type of professional group therapy”—Foster mentored Black business owners.[24] He helped them obtain grants and matched minority-owned businesses with “established corporate buyers.” Under Foster’s leadership, the NBL worked with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Operation Breadbasket to provide entrepreneurs with seminars about topics like accounting trends and business law.

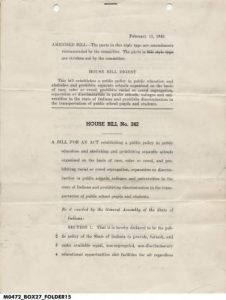

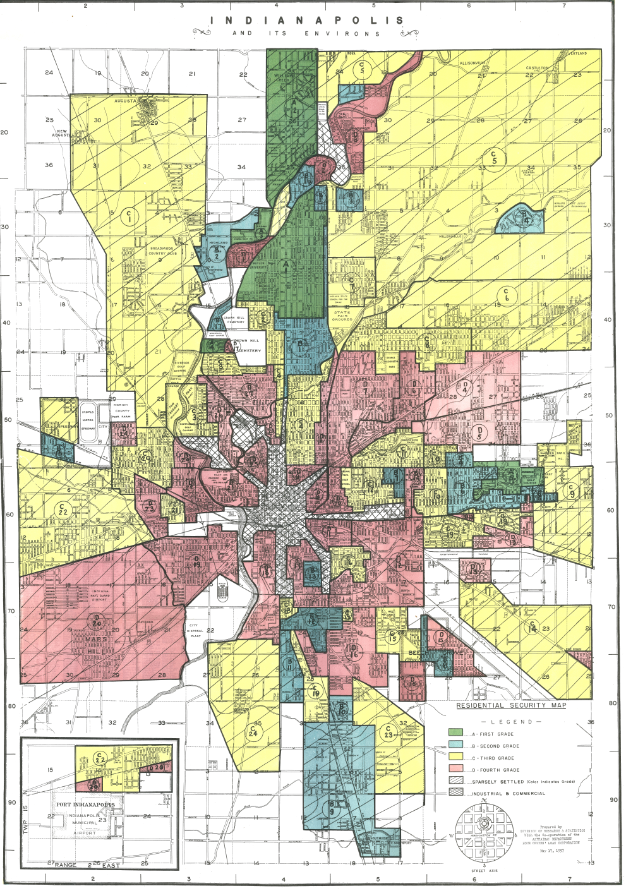

Of this work, Foster said “We’re living in a new day and working with a new Negro who is more professionally and economically mature . . . Negro businessmen today realize that they can not stand a chance individually. They must unite and mobilize their resources for a stronger voice and larger economic base.”[25] He also worked to increase capital for minorities by co-founding the Midwest National Bank in 1972. The bank publicly objected to redlining practices, issued “inner-city” loans, and appointed women to several leadership positions.[26]

Despite cultivating a small empire and a reputation as a civic-minded leader, Foster’s proverbial boots were nearly confiscated. In 1974, he was arrested for allegedly operating an interstate heroin ring.[27] His arrest followed a “‘super secret'” investigation conducted by the FDA and Indianapolis Police Department narcotic squad, which purported that he violated the Indiana Controlled Substances Act. The following year, the Indianapolis Star reported that a Marion County grand jury exonerated Foster, claiming in an eight-page report that his arrest was “‘politically motivated.'”[28] The report concluded that he was arrested because two informants were promised leniency in other cases against them if they would implicate Foster. Jurors opined, “‘We believe Andrew Foster has personally suffered a great deal as a result of these indictments.'”

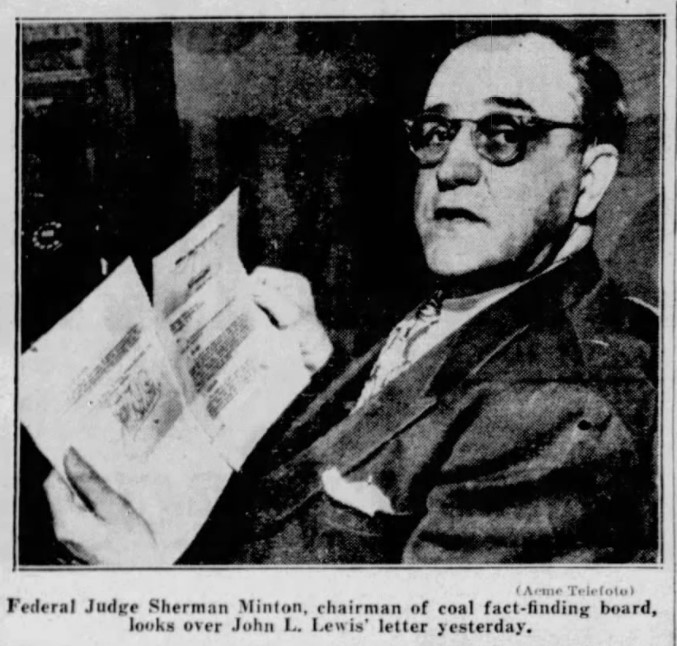

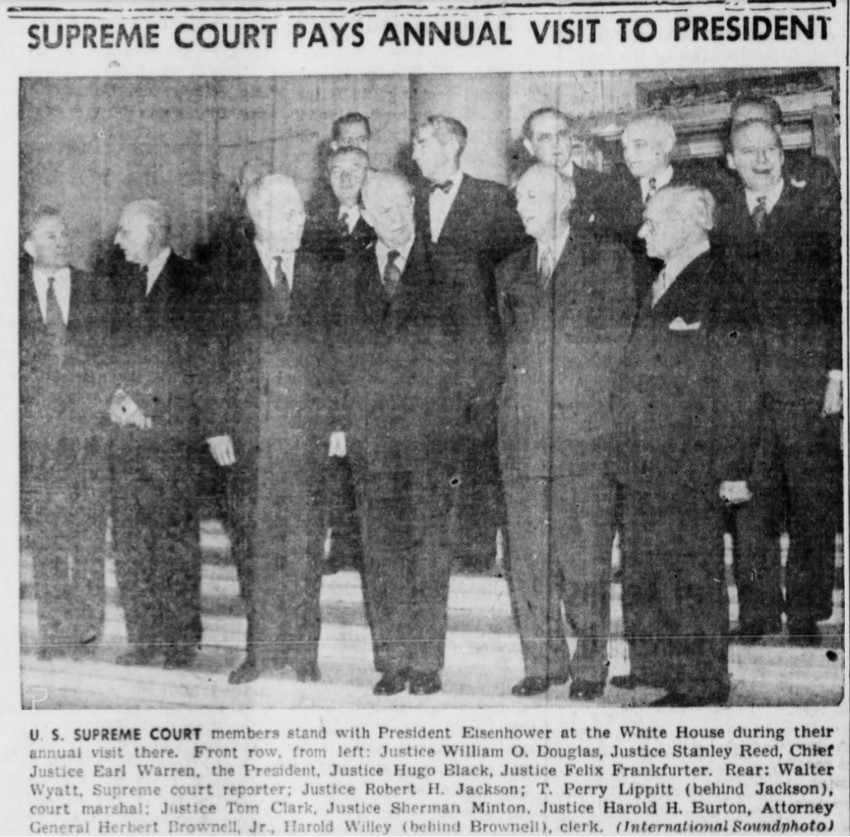

Foster elaborated on this suffering. He told the Indianapolis Star that his wife was afraid to stay at home, fearing that the allegations would induce individuals in the drug trade to “‘kidnap one of our children or break into our home to rob us.'”[29] Another ramification of the indictment was Foster’s resignation from the board of the Midwest National Bank. He told the Star, “‘I was a successful black businessman and the younger blacks could look up to me and see a model for success,'” but after the arrest and prosecutors’ statements “some of the younger blacks felt I was discredited.'”[30] In his pursuit of accountability, Foster filed suit against Marion County Prosecutor Noble Pearcy and Chief Trial Deputy Leroy New for defamation.[31] Over the course of years and various appeals, the state ruled against Foster, concluding that “‘the prosecutor and his assistant were immune from being sued for anything they said in their official capacity.'”[32] The U.S. Supreme Court sided with the state.

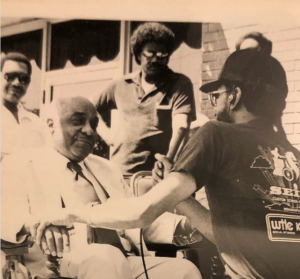

The arrest ultimately failed to tarnish his reputation, which he went to various length to defend, including voluntarily taking a lie detector test.[33] He certainly felt a sense of gratification when hundreds gathered to celebrate “Bo Foster Day” on August 24, 1982.[34] At the event, the Marion County Sherriff’s Department presented him with a plaque, and Joe Slash, the city’s first Black deputy mayor, presented him with a letter from Mayor William Hudnut. Foster was also bestowed with the prestigious Sagamore of the Wabash, which Governor Robert Orr awarded in recognition of his civic contributions.[35] The Indianapolis Recorder profiled the event and predicted “In the years to come the children and grandchildren of Mr. and Mrs. Foster will remember him as a man who contributed endlessly to the well being of the Hoosier state and of his admiring contemporaries . . . a man who lived the American Dream.”[36]

Andrew “Bo” Foster passed away in 1987, having increased capital and equity for Indianapolis’s Black community.[37] In the 1990s, Foster Motor Lodge and adjoining Pearl’s Lounge were demolished.[38] Fittingly, the site was replaced with the Hamilton Center, a non-profit mental health organization. This would be the location of a historical marker installed in 2023 to commemorate Foster. His family shares his sense of stewardship. His grandson, Charles, applied for the marker and manages a robust Instagram account documenting Foster’s life to ensure his legacy endures.

The marker dedication was a joyous occasion, one that resembled a family reunion. Relatives flew from across the country to commemorate the patriarch and learn about the Indianapolis of his time. Also in attendance was Joe Slash, who was effusive in his praise of Foster and his enduring impact. He and family members passed around a microphone, sharing memories and anecdotes that affirmed the Recorder‘s prediction.

Notes:

[1] Skip Hess, “No ‘Bootstraps,’ So NBL Evolves,” Indianapolis News, June 27, 1968, 56, accessed Newspapers.com.

[2] Andrew Foster Legacy Inc. Instagram account, managed by Charles Foster Jolivette. The account includes several primary sources, including newspaper clippings and images.

[3] Robert Corya, “Dust Nothing New to Andrew Foster,” Indianapolis News, August 26, 1969, 24, accessed Newspapers.com; “Success Hasn’t Spoiled Bo,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 22, 1983, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[4] Photograph, Andrew Foster, January 1, 1938, Crispus Attucks High School Collection, accessed Indianapolis Public Library Digital Collections; Photograph, Crispus Attucks Alumni, December 9, 1983, accessed Indiana Historical Society Digital Image Collections.

[5] Robert Corya, “Dust Nothing New to Andrew Foster,” Indianapolis News, August 26, 1969, 24, accessed Newspapers.com.

[6] “Andrew Daniel Foster,” U.S. World War II Draft Cards, Young Men, 1940-1947, Registration Date: October 16, 1940, accessed Ancestry Library; “Service Roll: Inductions and Enlistments into U. S. Forces,” Indianapolis News, October 21, 1941, 8, accessed Newspapers.com; Indianapolis Star, March 2, 1943, 22, accessed Newspapers.com; Corya, “Dust Nothing New to Andrew Foster,” Indianapolis News, 24.

[7] The Saint, “The Avenoo,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 27, 1957, 12, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Corya, “Dust Nothing New to Andrew Foster,” Indianapolis News, 24; “Andrew D. Foster, Owned Motor Lodge,” Indianapolis News, June 25, 1987, 39, accessed Newspapers.com; “The ‘New’ Pearl’s Management is Sponsoring Andrew ‘Bo’ Foster Memorial/Appreciation Day May 28,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 21, 1988, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[8] “Andrew Foster,” 1950 United States Federal Census, accessed Ancestry Library; George Vecsey, “For Many, It was Just Another Weekend,” New York Times, February 15, 1971, 13, accessed timesmachine.nytimes.com; Andrew Foster Legacy Inc. Instagram account.

[9] “Success Hasn’t Spoiled Bo,” Indianapolis Recorder, 1.

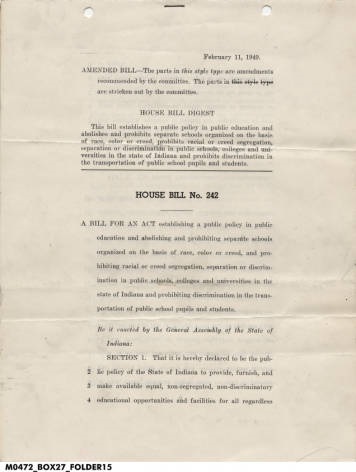

[10] Indianapolis Recorder, February 5, 1949, 7, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “’House of Strangers’ at Walker Sunday,” Indianapolis Recorder, October 8, 1949, 12, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[11] “Indianapolis,” The Negro Travelers’ Green Book: The Guide to Travel and Vacations (1955 Edition): 20, accessed New York Public Library Digital Collections; “Indianapolis,” Travelers’ Greek Book (New York City: Victor H. Green & Co., 1966-1967): 24, accessed New York Public Library Digital Collections; Alexandria Burris, “How the ‘Great Book’ Helped Black Motorists Travel across Indiana,” IndyStar, February 16, 2022, accessed indystar.com. (Foster Hotel and Guest House were printed in issues from 1955 to 1977).

[12] “Foster Opens Hotel in Downtown Section,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 22, 1955, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; Indianapolis Recorder, August 13, 1955, 7, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; The Saint, “The Avenoo,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 27, 1957, 12, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; The Saint, “The Avenoo,” Indianapolis Recorder, June 29, 1963, 12, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Ad, Indianapolis Recorder, July 8, 1967, 6, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[13] Ad, “Welcome Permanent Guest,” Indianapolis Recorder, February 6, 1954, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; The Saint, “The Avenoo,” Indianapolis Recorder, September 24, 1966, 10, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Corya, “Dust Nothing New to Andrew Foster,” Indianapolis News, 24; “Success Hasn’t Spoiled Bo,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 22, 1983, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[14] Robert Corya, “Dust Nothing New to Andrew Foster,” Indianapolis News, August 26, 1969, 24, accessed Newspapers.com.

[15] “Foster Opens Hotel in Downtown Section,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 22, 1955, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[16] Jet (November 11, 19540): 46, submitted by marker applicant.

[17] “Marriage Licenses,” Indianapolis Star, May 1, 1962, 30, accessed Newspapers.com; Ad, “Pearl’s Cocktail Lounge,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 9, 1970, 11, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Success Hasn’t Spoiled Bo,” Indianapolis Recorder, 1; “The ‘New’ Pearl’s Management is Sponsoring Andrew ‘Bo’ Foster Memorial/Appreciation Day May 28,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 21, 1988, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[18] “Success Hasn’t Spoiled Bo,” Indianapolis Recorder, 1.

[19] Indianapolis Recorder, October 17, 1970, submitted by marker applicant.

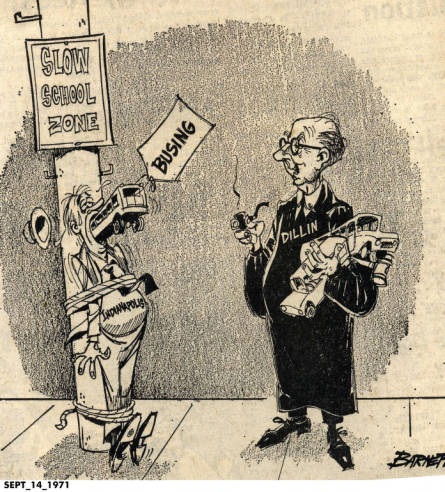

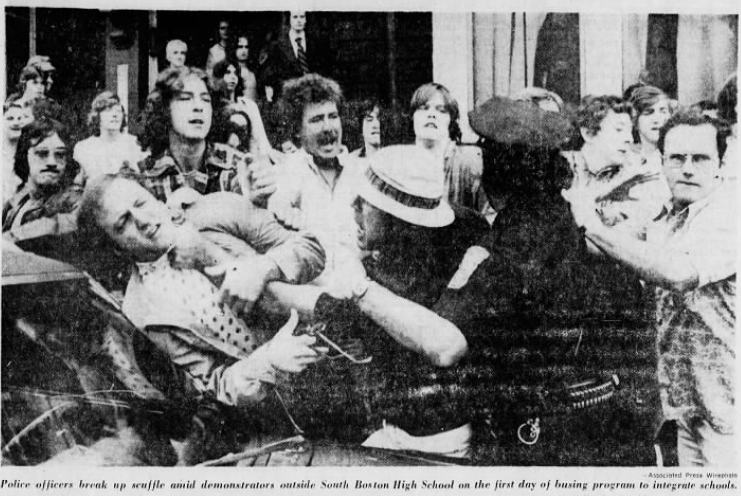

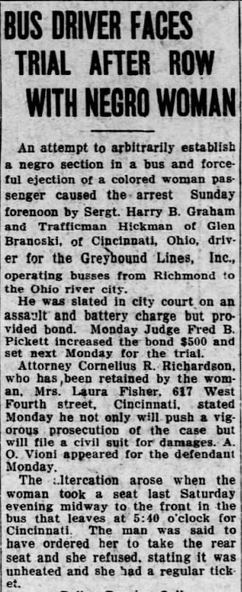

[20] Renee Ferguson, “NAACP Leader Denounces Bills Prohibiting Busing,” Indianapolis News, February 23, 1972, 10, accessed Newspapers.com; “Women’s Luncheon Every Monday at Pearl’s Lounge,” Indianapolis Recorder, August 17, 1974, 5, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Indianapolis Recorder, October 9, 1976, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Let’s Go: Leisure Time Calendar,” Indianapolis Star, February 27, 1983, 83, accessed Newspapers.com; “Special Notices,” Indianapolis News, October 26, 1984, 33, accessed Newspapers.com.

[21] “Pacers Get-Acquainted Buffet at Pearl’s Nov. 3,” Indianapolis Recorder, October 25, 1975, 4, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[22] “Black Republicans Enjoy Reception,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 2, 1971, 4, accessed Newspapers.com; “One Man in Life,” Indianapolis Recorder, October 6, 1973, 15, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Group Raises $67,075 for Lugar Campaign,” Indianapolis News, March 13, 1974, 20, accessed Newspapers.com; “Hudnut, GOP Mayoral Candidate, Plans Active Recruitment Program for Blacks,” Indianapolis Recorder, October 4, 1975, 1, 17, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Black Republicans Cite Kuykendall, Ms. Holland,” Indianapolis Recorder, February 28, 1976, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “C. Delores Tucker Arranges Series of Weekend Talks,” Indianapolis Star, October 10, 1976, 86, accessed Newspapers.com; William J. Sedivy, “Socialist Workers Vice Presidential Candidate in City,” Indianapolis Star, September 15, 1984, 22, accessed Newspapers.com.

[23] “Black Republicans Enjoy Reception,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 2, 1971, 4, accessed Newspapers.com; Sedivy, “Socialist Workers Vice Presidential Candidate in City,” Indianapolis Star, 22, accessed Newspapers.com.

[24] Pat W. Stewart, “Operation Breadbasket Ministers Outline Broad Program for Action in the City,” Indianapolis Recorder, December 30, 1967, 1, 14, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; John H. Lyst, “Negro Firms to Get Push,” Indianapolis Star, May 2, 1968, 73, accessed Newspapers.com; L. J. Banks, “NBL Ready to Aid Negro Businessmen,” Indianapolis News, December 4, 1968, 78, accessed Newspapers.com; “Opportunity Fair to Aid Minorities,” Indianapolis News, July 29, 1970, 25, accessed Newspapers.com.

[25] Banks, “NBL Ready to Aid Negro Businessmen,” Indianapolis News, 78.

[26] Robert Corya, “80,000 Shares OK’d for Newest City Bank,” Indianapolis News, April 20, 1971, 5, accessed Newspapers.com; “New Midwest National Bank Gets Approval to Sell Common Stock,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 24, 1971, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “The Best Kept Secret in Town: Midwest National Bank,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 28, 1981, 22, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[27] “Health Board Member Among 7 Arrested on Drug Indictments,” Indianapolis Star, September 7, 1974, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

[28] Joseph Gelarden, “Jury Calls Indictment ‘Politics,'” Indianapolis Star, May 24, 1975, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] “Judge is Ordered to Consider Suit,” The Herald [Jasper, MI], June 21, 1978, 18, accessed Newspapers.com.

[32] “From Libel Suit: Court,” The Times [Munster, IN], April 4, 1979, 9, accessed Newspapers.com; “High Court Denies Hoosier’s Appeal,” Daily Reporter [Greenfield, IN], April 15, 1980, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[33] Andrew Foster Legacy Inc. Instagram account.

[34] “Bo Foster’s Day,” Indianapolis Recorder, September 4, 1982, 1, 8, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[35] William “Skinny” Alexander, “Time for Talk,” Indianapolis Recorder, September 4, 1982, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[36] “Bo Foster’s Day,” Indianapolis Recorder, 1, 8.

[37] “Andrew Daniel Foster, Sr.,” Indiana State Board of Health Medical Certificate of Death, June 23, 1987, Indiana, U.S., Death Certificates, 1899-2011, accessed Ancestry Library; “Andrew D. Foster, Owned Motor Lodge,” Indianapolis News, June 25, 1987, 39, accessed Newspapers.

[38] Mary Francis, “McLean Place was Truly Foster’s Place, and Now It’s Official,” Indianapolis Star, November 16, 1994, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; Howard M. Smulevitz, “New Mental Health Center will Stand on Site of Historic Lounge and Lodge,” Indianapolis Star, September 7, 1996, 16, accessed Newspapers.com.