On January 11, 1898, a special meeting occurred of the South Side Turnverein, one of Indianapolis’ premier social clubs for German Americans. It was the sixtieth birthday of the organization’s president, Henry Victor. The group heaped “tokens of esteem” on their beloved leader, according to the Indianapolis Journal, which further wrote, “the occasion had the effect of bringing Mr. Victor to tears.” The esteem afforded to Victor was no faint praise; in many respects, he was the main reason the South Side Turnverein met that night, and many others, at all.

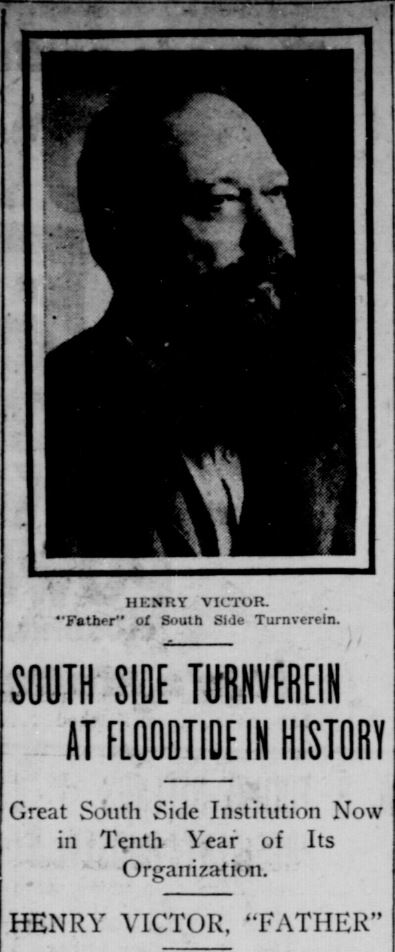

Only a few years earlier, previous leadership had barely gotten the organization off the ground. It wasn’t until Henry Victor took over in 1894 that the South Side Turnverein expanded and flourished, providing its members with athletic activities, social functions, and cultural events. Years later in a glowing article, the Journal noted Victor’s work for the organization, calling him the “‘Father’ of the South Side Turnverein” and writing, “to Henry Victor is due the success the club has attained.”

A German immigrant with a passion of business, Victor epitomized the promise that America held for so many newcomers in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. His successful management of Mozart Hall, one for Indianapolis’s top bars and restaurants, the growth of the South Side Turnverein, and his involvement in numerous civic organizations spoke to his energy and talent for bringing people together to build vibrant communities. As such, the impact he left on the people he served, both at his businesses and with his leadership, provides us with a compelling example of the German American experience in Indiana.

Victor was born on January 11, 1838, in Pommern, Germany, which today sits between Eastern Poland and Western Germany. He lived in Europe for most of his life, becoming “a successful businessman, dealing in silks and dress goods, [and] was also connected with a private bank and was worth considerable money,” noted the Indianapolis News. He likely immigrated to the United States and moved to Indianapolis sometime between 1887 and 1891, as a relatively older man. What would spur a successful businessman in his native land to come to the U.S.? Like a major reversal of fortune. As the News added, “he was stricken with an affliction of the eyes which threatened him with total blindness. He was taken to a hospital, where he remained for several months, during which time losses occurred in his business, and he left Germany practically a broken man.” Like so many who left for the shores of America during that age, he left to restart, and hopefully improve, his life.

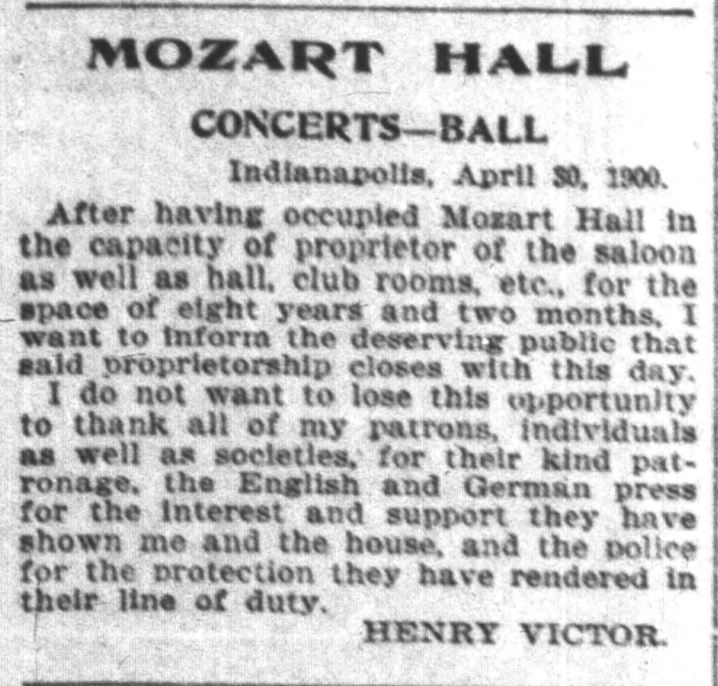

Once in Indianapolis, he got involved in the brewery business, working as a collector for the Terre Haute Brewing Company, which led to his entry into the saloon business. It was in this field that he made his name in the Circle City, with his management of Mozart Hall. In 1892, Victor took over as manager of the decades-old Indianapolis bar and restaurant at 37 South Delaware Street. It didn’t take long for the press to sing his praises. The Indianapolis Journal wrote, “Mr. Victor is one of those whole souled persons who makes friends with everyone he meets, and will not lack in entertaining his customers in that inimitable way he was in conferring with his fellow citizens.” Of Mozart Hall, the article further noted that “none will find a more congenial place in the city to spend a few minutes to pass away the idle moments of the day.”

Upon assuming management of Mozart Hall, Victor placed ads in Indianapolis’s premier German-language newspaper, the Indiana Tribüne, which described for his community what patrons could expect.

The ad read, roughly translated:

Mozart Hall!

Henry Victor.

The biggest, prettiest and oldest beer-style eatery in town. The spacious and beautifully furnished hall is available for clubs, lodges and private individuals to hold balls, concerts and meetings under liberal conditions.

As the ad declared, Mozart Hall not only served individual customers, but became a meeting place for many organizations, such as unions and benevolent associations. In today’s language, Mozart Hall would be called a “maker space,” a congenial, well-furnished building for work, philanthropy, and entertainment.

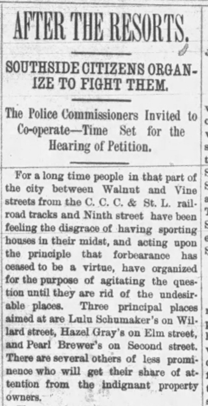

When he wasn’t hosting civil society, Henry Victor actively participated in it. In 1894, he served as the secretary of the Indiana Liquor Dealer’s Association, which met at Mozart Hall. The association advocated policies they believed would “clean up” the liquor business, including regulations on liquor licenses. As the Indianapolis News reported, “a feeling is growing that only decent people should be granted liquor licenses, and that a protest will be entered against granting liquor licenses to ex-convicts, gamblers, violators of the law, and immoral characters.” Additionally, Victor advocated for policies that would make it easier for breweries to start up and provide its product to local businesses, something that clearly benefitted the German immigrant community he was a part of.

However, his involvement in organizations didn’t always go smoothly. In 1895, he very publicly resigned from the Saloon Keeper’s Union, over disagreements about the implementation of a new liquor law, called the “Nicholson Law,” which placed limitations on gambling, saloons, and underage drinking. Before the national experiment of Prohibition, many state and local laws were implemented in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth centuries, as a way to control the ill effects of the liquor trade. However, fierce debates ensued as to how these laws should be followed. In his resignation letter, Victor argued that he was in favor of following these laws and challenging his critics. He wrote:

Many of you members have seen fit to criticize myself and others who have constantly labored for the interest and elevation of the retail trade; and such criticisms have practically gone in public print, and I do not want to be further annoyed this way as in the past, so I will in the future use what influence I possibly have to elevate and regulate the retail business according to my own way.

Former union colleague William G. Weiss, in the Indianapolis Journal, shot back at Victor, arguing that he withdrew because “Mr. Victor is not in sympathy with the union in regard to obeying the law.” Who was right? In the murky territory of pre-Prohibition liquor law, it was often difficult to effectively determine the letter of the law, which led to fierce debates like Victor’s with the Saloon Union. Nevertheless, Victor successfully ran Mozart Hall for many years, earning a reputation as an honest and friendly businessman.

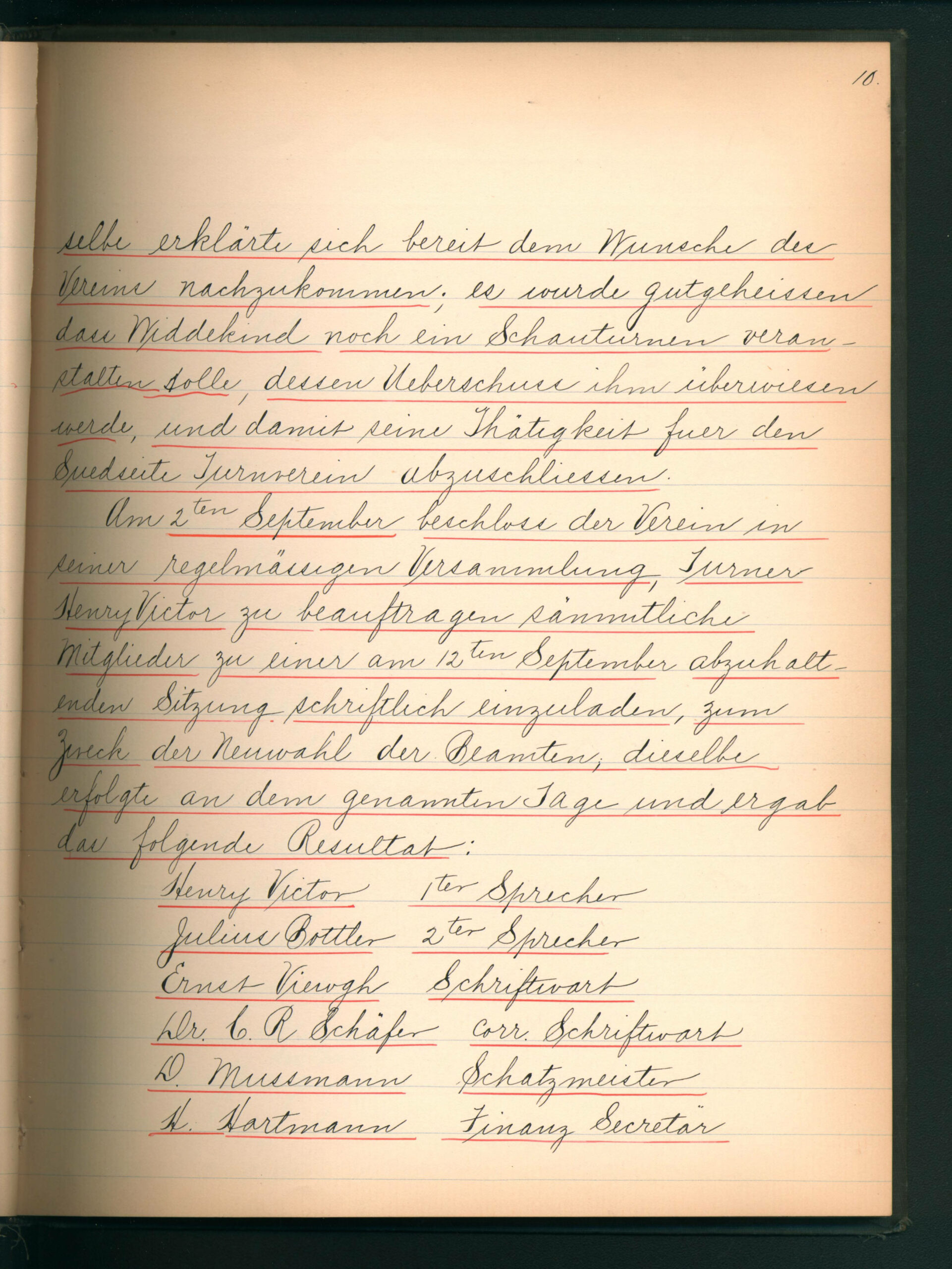

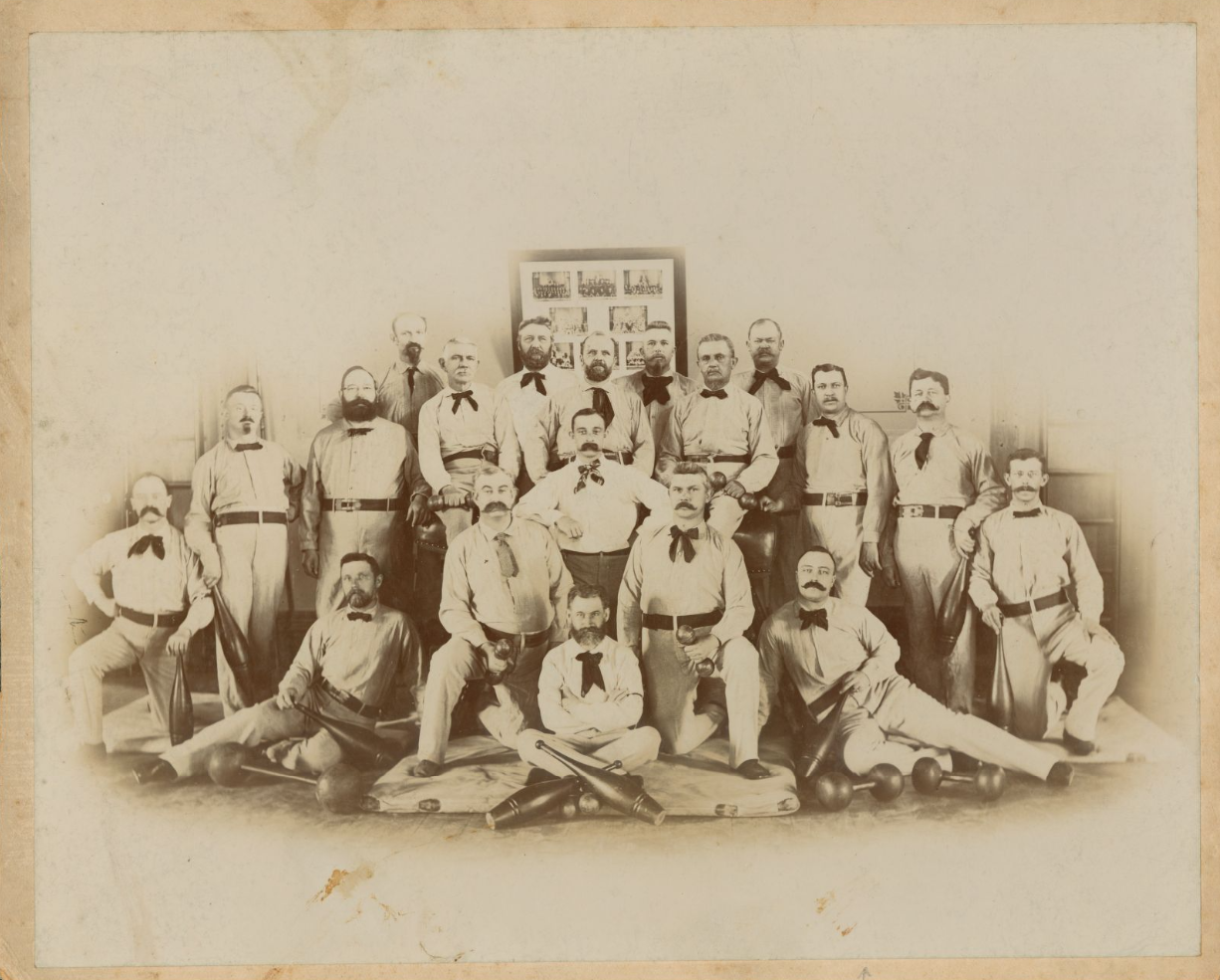

As his stature in the community grew, so did his involvement in a variety of organizations, the most important of which was the South Side Turnverein. Turnvereins, or Turner Clubs, were a mainstay of German American life during the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth centuries. Founded on the principle of “sound body and mind,” the Turnverein movement was spearheaded by German educator Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, who believed physical exercise and cultural activities led to a healthy life. The South Side Turnverein in Indianapolis, founded on September 24, 1893, began as an offshoot of another organization when about 200 German Americans left the Socialer Turnverein to form their own gymnastics club on the south side. During its first few months, the South Side Turnverein and its members experienced challenges growing the group. That all changed when the membership elected Henry Victor as President, or “First Speaker,” of the organization in September of 1894. He threw himself into the role, rapidly expanding the club’s memberships and activities.

As the Indianapolis Journal wrote of Victor:

Mr. Victor took charge of the work in the spring of 1894, when all efforts to complete the organization and make it a success had failed, and at a time when those supporting the society were losing faith in the undertaking. The enthusiasm and the effectiveness with which he assumed control of the work inspired those interested, and at once new life was put into the organization, and in less than a year a membership of had been secured.

In the next few years, the South Side Turnverein participated in a wide variety of athletic and cultural events. In 1894 alone, the Turnverein hosted a “gymnastic entertainment” at English’s Opera House, produced a “two-act play” called “He Lost His Gloves,” and participated in Indianapolis “Wald-Fest” or “forest festival.” The club was also heavily involved in the larger German community, supporting other Turnvereins and social clubs. In 1898, members of the South Side Turnverein attended a “kommers,” or “students’ entertainment” at the newly opened German House in Indianapolis and some of its members served on the leadership committee of the North American Turnerbund, which decided to move its national headquarters from St. Louis to Indianapolis. Leading by example, Victor’s energy and dedication to the club galvanized the South Side Turnverein and its members.

Arguably his greatest accomplishment as South Side Turnverein president was overseeing the building of its hall, serving as one of the South Side Turnverein Hall Association’s directors. Leading such a large financial endeavor proved natural to Victor, as his experience with Mozart Hall as well as the German Mutual Insurance Company prepared him for the task. Plans to build the hall started on February 20, 1900, when the South Side Turnverein decided to purchase 150 feet of property on Prospect Street at a cost of $5,000. On March 7, Victor and others filed articles of incorporation for the South Side Turnverein Hall Association, whose charge was to “purchase real estate and to sell the same and particularly to construct and erect for the South Side Turnverein a suitable gymnasium.”

The Association chose Vonnegut & Bohn, one of Indianapolis’s best architecture firms, to design and build their hall, and by June 1900, the Association held the groundbreaking ceremony. Victor, the man responsible for so much of the organization’s success, “dug the first spade of full of dirt and in his speech wished the building progress,” according to the Indianapolis Journal. An illustration of the prospective building appeared in the Indianapolis News on June 7, 1900, with further details on its facilities:

The interior will be arranged with all the appointments of a modern club house. The basement, which will be a full story in hight [sic], will contain the kneipe [bar], bowling alleys, dining-room, women’s parlor, women’s and men’s dressing rooms and shower baths. The main floor will be almost entirely taken up by the large hall, which is also to be used as a gymnasium. This hall will seat, together with gallery, about 700 people. At the east end of the hall there will be a large and well equipped stage. Stretching along the other end of the hall will be a large foyer, with stairways leading to the basement and gallery.

After months of intense work, the South Side Turnverein Hall was completed, and on December 2, the club opened its hall to the public, on the organization’s eight-year anniversary. “In the afternoon the new building was thrown open to the public,” the News reported, “and it was inspected by a large number of visitors.”

The South Side Turnverein formally dedicated its new hall on January 20, 1901, with 3,000 people in attendance. Victor christened the new building along with Fred Mark, chairman of the building committee, Herman Lieber, president of the North American Turnerbund, and Charles E. Emmerich, superintendent of the Manual Training School, among others. The building and grounds had a cumulative cost of $25,000, raised through its members by the association. A banquet for around 400 people was held the night after the dedication, with the News writing, “Henry Victor, as master of ceremonies, welcomed the representatives of the various German societies at the ‘kommers,’ [or students’ entertainment] with which the South Side Turnverein last night closed the dedicatory services of its new hall. Many women were among the 400 guests and the evening was enjoyable.” In only a a few years, Henry Victor transformed the South Side Turnverein from a small but promising organization into one of Indianapolis’ leading social clubs for the German American community.

The membership of the South Side Turnverein reelected Henry Victor to President many times and he continued to serve with distinction until 1905. However, towards the end of this life, he shifted gears to help organize a singing society. A long-time singer with the Fourth Christian Church with a “good voice,” as described by the Indianapolis News, Victor helped incorporate the “The Suedsite Liedertafel,” or “South Side Singing Society” in 1910. He served as the president and the organization performed regularly at the South Side Turnverein. Boasting over 200 members and nearly fifty active members, the organization maintained a men’s chorus, a women’s chorus, and a children’s chorus. The society served as more than just an outlet for those who loved to sing; it also wanted to preserve German culture. As the News reported, “in addition to the singing, the society endeavors to conserve a correct use of the German language.”

Unfortunately, his work with the South Side Singing Society was tragically cut short when he died on September 24, 1910, after a week in the hospital following a stroke. Many German American societies attended his funeral at the South Side Turnverein Hall, and some sang music in tribute, something he likely would have appreciated. The Indianapolis Star wrote in his obituary that “Mr. Victor was interested in the South Side Turnverein and the flourishing condition of the society is attributed largely to his efforts.” In addition to the South Side Turnverein, he belonged to the Columbia Lodge, the Knights of Pythias, and the German Heritage Society, to name a few. Newspaper accounts noted that he was a “marked personality among Germans of city” and “a man of mystery, and it was not known what were his family relations previous to coming to this city [Indianapolis].” He left behind a $60,000 estate, a testament to his acumen for business.

The life of Henry Victor is but one extraordinary story among the annals of the German American experience in Indiana. A man whose former home left him nearly destitute, he set out for the United States to build a better life, and his decades in Indianapolis served as a prime example of his ability and devotion to the community he called his own. From his successful management of Mozart Hall to his trailblazing leadership of the South Side Turnverein, Victor left a large impression wherever he went in Indianapolis, gaining a reputation for hard work and honest entrepreneurialism. He also dedicated himself to the preservation of German culture through his South Side Singing Society, another fruitful organization he helped found merely months away from his death. In all that he was, Henry Victor personified not only German Americans, but German Hoosiers, an immigrant community that profoundly shaped the history of the State of Indiana.

![Instep-arch support patent [marketed as Foot-Eazer], Publication date April 25, 1911, accessed Google Patents](http://blog.newspapers.library.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/1911-Instep-Patent.png)

![Elevated Railroad Station at East Madison Boulevard and Wells Street [near Scholl's building] November 1, 1913, Chicago Daily News Photograph, Chicago History Museum, accessed Explore Chicago Collections, explore.chicagocollections.org/image/chicagohistory/71/qr4p14f/](http://blog.newspapers.library.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/train-station-at-Wells-and-Madison-CHicaho-History-Museum-300x243.png)