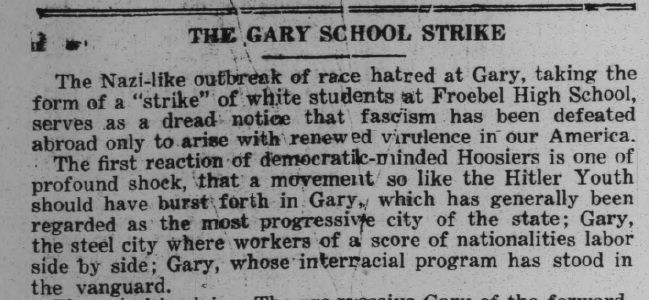

On September 18, 1945, hundreds of white students at Froebel School walked out of their classes to protest African American students at the institution. According to the Gary Post-Tribune, the striking students “urged that Froebel school be reserved for whites only” or that they be transferred to other schools themselves.

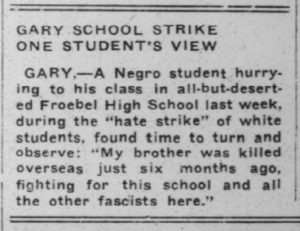

While the conflict between segregation and integration was far from new, the student strike in Gary would call into question the very values the United States fought to uphold during World War II, which had formally ended just two weeks before the “hate strike.” The Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance, composed of black ministers, made this point clear when it issued its “appeal to reason” to the citizens of Gary, Indiana:

It is indeed regrettable to note that after the nation has spent approximately 190 billion dollars, the colored citizens of Gary have sent about 4,000 of their sons, brothers, and husbands to battlefields around the world and have supported every war effort that our government has called upon us to support, in a united effort to destroy nazism and to banish from the face of the earth all that Hitler, Mussolini, and Tojo stood for; to find in our midst those who are endeavoring to spread disunity, race-hatred, and Hitlerism in our community.

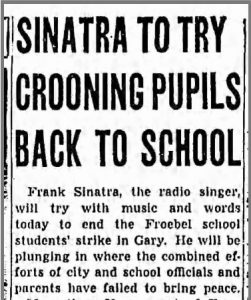

Gary Post-Tribune, September 20, 1945, 3

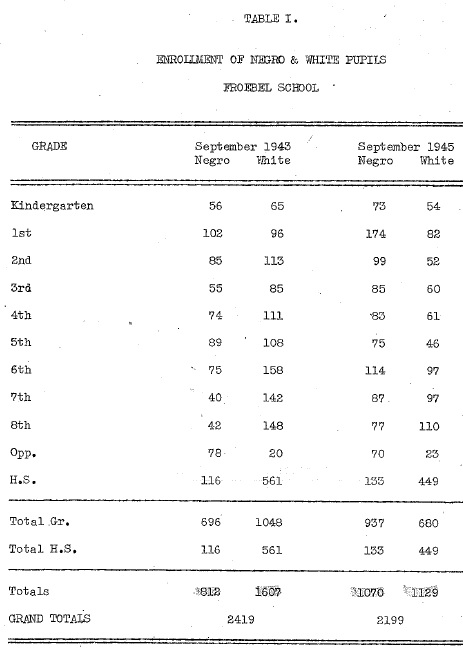

Integration was not a recent development at Froebel when much of the white student body went on strike in the fall of 1945. In fact, Froebel was Gary’s only “integrated” school throughout the first half of the 20th century, though the term warrants further explanation. When the K-12 school opened in 1912, Gary school officials recognized that African American students should not be denied the opportunities available to white students at the new school and established two separate rooms at Froebel for black students. By 1914, a report published by the United States Bureau of Education indicated that there were approximately seventy black students attending the school, but that “the other patrons of the school, most of whom are foreigners, strenuously object to mixing colored children with the others; so they are placed in separate classes in charge of two colored teachers. . .” Thus, despite integration, Froebel remained internally segregated.

A 1944 study conducted by the National Urban League showed that Froebel’s black students were “welcomed as athletes, but not as participants in cultural and social affairs.” They could not use the swimming pools on the same days as white students, were barred from the school band, and were discriminated against in many other extracurricular activities.

Conditions at Froebel improved slightly during the 1940s, due in part to Principal Richard Nuzum. He created a biracial Parent-Teachers’ Association, integrated the student council and boys’ swimming pool, and enabled black students to try out for the orchestra. Unfortunately, his efforts towards further integration angered many of Froebel’s white students and their parents, who would later criticize Nuzum of giving preferential treatment to African American students. These feelings, paired with a rising fear among many of Gary’s white, foreign-born inhabitants about increases in the black population in the city, largely contributed to the 1945 school strike.

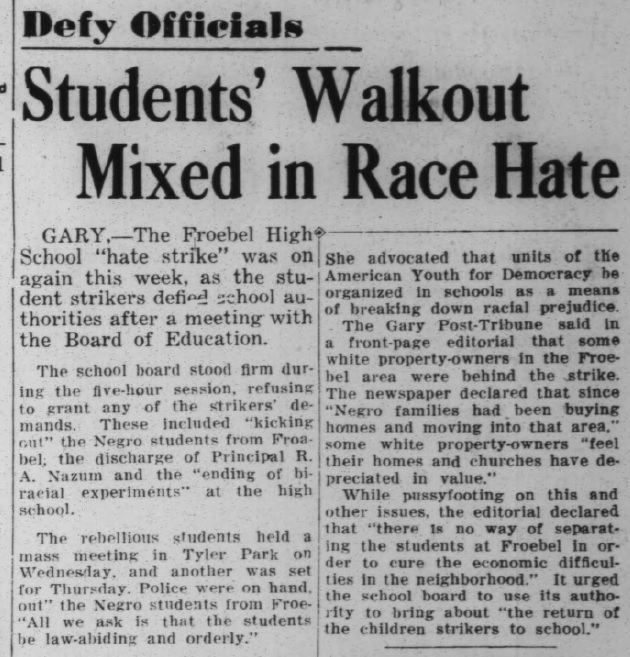

Newspapers across the state covered the strike(s) extensively throughout the fall, and the story quickly made national headlines. By September 20, the strike spread to Gary’s Tolleston School, where approximately 200 additional students skipped classes. On September 21, 1945, the Gary Post-Tribune reported that between the two schools, well over 1,000 students had participated in the walkouts up to this point.

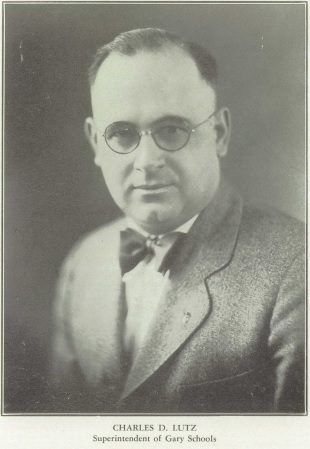

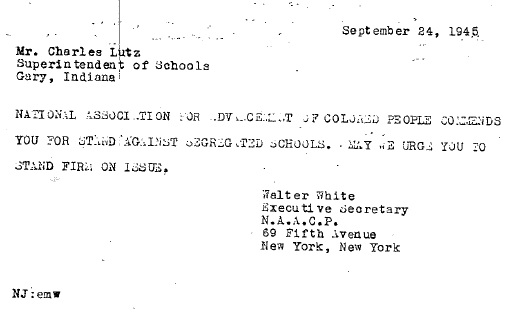

Eager to see an end to the strike, to avoid potential violence, and to get students back to school, Superintendent Charles D. Lutz and the board of education issued a formal statement on Friday, September 21, demanding that students return to classes on Monday. The school board threatened to take legal action against parents of students under age sixteen if they continued to strike, while those over age sixteen risked expulsion.

The school board was not alone in its hopes of ending the strike. Gary Mayor Joseph E. Finerty, the Gary Council of Churches, and the school PTA all issued appeals hoping to bring an end to the walkouts. Other opponents of the strike included the NAACP and CIO United Steel Workers Union. Many blamed parents of the striking students for the racial tension existent in the school, stating that racial hatred was not inherent, but learned at home. A September 26, 1945 editorial in the Gary Post-Tribune also noted:

Fundamentally this is not a school problem. It has developed out of the changing population in the Froebel area. . . As a result of this influx of Negro families some white property owners feel their homes and churches have depreciated in value.

While students at Tolleston agreed to return to classes by the school board’s stated deadline, those leading the strike at Froebel refused to return until Wednesday, and only on the condition that the school board meet with them beforehand and comply with their demands.

These demands, which the Gary Post-Tribune published on September 21, were three-fold: 1) the removal of all 800 black students from Froebel; 2) the ousting of Principal Richard Nuzum, whom they believed gave preferential treatment to black students; and 3) that school officials stop using Froebel students as “guinea pigs” in race relation experiments (Froebel was the only high school in Gary with a racially mixed attendance at the time).

The Gary school board met with the striking committee on September 25, and when it refused to give in to the students’ demands, the strike continued. Leonard Levenda, spokesman for the striking committee, was quoted in the Gary Post-Tribune on September 26, stating that the walkout was the result of “a long series of episodes provoked by the behavior of Negro students.” Levenda continued by blaming Nuzum for not taking action against African American students after these reported “episodes.” The strike continued until October 1, when students finally returned to classes after the school board agreed to formally investigate the charges against Principal Nuzum.

In response to the incidents at Froebel, Mayor Finerty urged the formation of an inter-organization racial unity committee to help improve race relations in the “Steel City.” Finerty, as quoted in the Indianapolis Recorder on October 20, stated “we in Gary must take positive steps in learning to live together in unity in our own city. Now, more than ever, there is need for unity within our city and the nation.”

Another article in the Recorder that day examined the reaction of white leaders in Chicago, who did little to conceal their disgust for the strike and criticism of the strikers:

These racist demonstrations have been an insult to democracy and to the hundreds of thousands of whites and Negroes who deplore this American form of Hitlerism. . . We further pledge not to walk out on democracy and on this problem which has its roots principally in the attitude and actions of the white man, not the colored.

In early October, the Gary school board appointed a special investigating committee and temporarily relieved Nuzum of his duties as principal. By October 21, the investigation came to a close and a report regarding conditions at Froebel was issued. Nuzum was exonerated and returned as principal and the report called for the school to return to the status it had before the strike. Angered by these results, students staged another walkout on October 29. Levenda and other striking students argued that they were not going on strike, but rather “being forced out by the actions of Mr. Nuzum.”

Searching for a way to bring a final end to the strike, Anselm Forum, a Gary-based community organization dedicated to social harmony, helped bring Frank Sinatra to the school to perform and talk with the students about racial tension in the city. While many students appeared attentive and understanding of Sinatra’s calls for peace and an end to racial discrimination, the striking committee refused to back down.

It was not until November 12, when State Superintendent of Public Instruction Clement T. Malan agreed to study conditions at Froebel that the striking students returned to classes. Even then, some mothers of the parents’ committee continued to oppose the students’ return.

Racial tension continued even after the strikes ended in November 1945. By the spring of 1946, students at Froebel threatened to go on strike again, but were stopped by the Gary school board and Froebel student council. Newspapers reported that the leaders of the previous strikes, in union with Froebel’s black students, issued an anti-strike statement in March 1946. In this statement, they encouraged the Gary school board to issue a policy to end discrimination in all of Gary’s public schools.

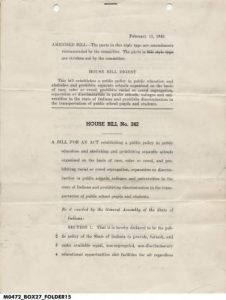

Due in large part to the “hate strikes” at Froebel, the Gary Board of Education adopted a policy on August 27, 1946, to end segregation and discrimination in the city’s public schools. Scheduled to go into full effect by September 1, 1947, the policy read:

Children under the jurisdiction of the Gary public schools shall not be discriminated against in the school districts in which they live, or within the school which they attend, because of race, color or religion.

In accordance with the policy, Gary’s public schoolchildren would attend the school nearest them and would be given equal opportunity “in the classroom and in all other school activities.” According to historian Ronald Cohen, the decision made Gary “one of the first northern cities to officially integrate its schools.” In 1949, the Indiana General Assembly passed a law to abolish segregation in the state’s public schools. The law required that schools discontinue enrollment on the basis of race, creed, or color of students.

Despite these measures however, discrimination in the Gary public school system did not disappear. Because of segregated residential patterns, few black students transferred to previously all-white institutions. The 1950s saw a resurgence in de facto segregation in the city as the black population there continued to grow and fill already overcrowded black schools.