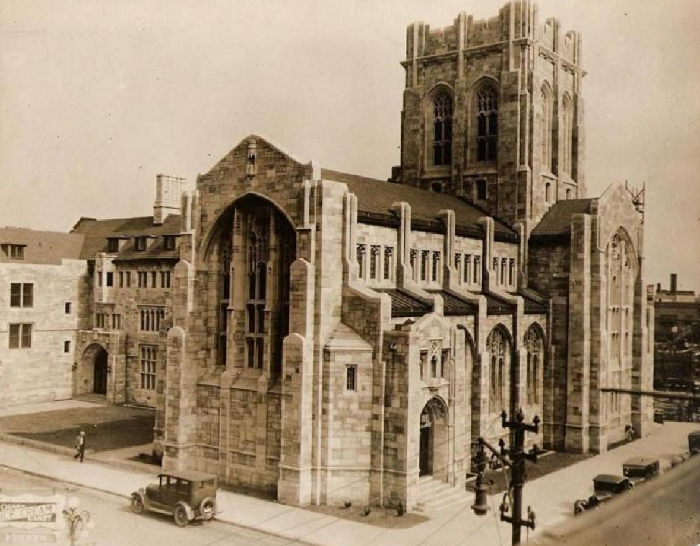

On the corner of Sixth Avenue and Washington Street stands a complex forged out of Indiana limestone. Plants creep through shattered windows, “UR MOM” is spray-painted across a balcony, and the scorched roof opens up into the heavens. The remains of Gary’s City Church represent very different things to onlookers. For some, they symbolize the unfulfilled promise of industrial utopia. For others like Olon Dotson, professor of Architecture and Planning at Ball State University and a Ph.D. candidate in Purdue University’s American Studies Program, “The remains of the structure serve as a monument to racism and segregation.” For most, it is simply the backdrop for a scene in Transformers 3. Few would disagree, however, that City Church embodies the rise and fall of Steel City.

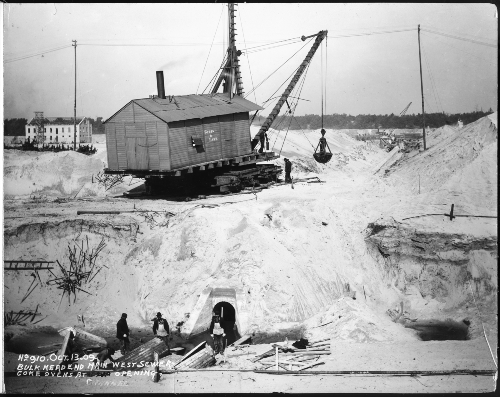

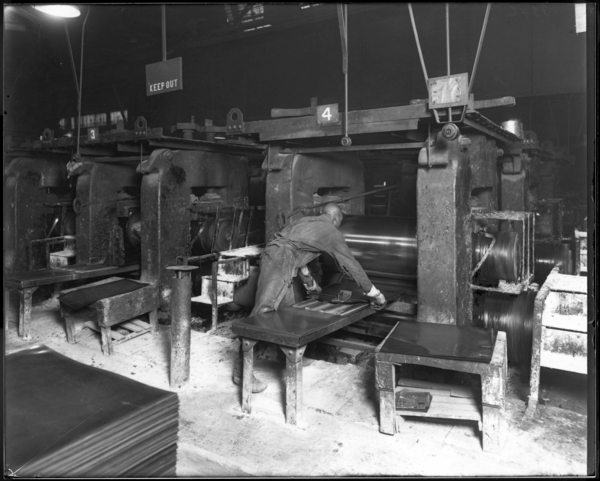

The church’s history is as nuanced as the feelings its remains inspire. The First Methodist Episcopal Church of Gary, was established in 1906, the same year the United States Steel Corporation gave birth to the city. The company converted acres of swampland and sand dunes, and soon Gary—named after U.S. Steel founding chairman Elbert Henry Gary—found itself dominated by steel mills. The expanding market for steel shaped the city’s built environment and encouraged population growth there. Between 1906 and 1930, increasing numbers of European immigrants, Black Southerners, Mexicans, and white migrants flocked to the region looking for work in the steel industry.

Historian James B. Lane contended that “Because of U.S. Steel’s limited concept of town planning, two strikingly different Gary’s emerged: one neat and scenic, the other chaotic and squalid.” Businessmen, as well as skilled plant operators and managers, settled North of the Wabash Railroad tracks. They resided in Gary Land Company’s subdivisions among paved streets, quaint homes, and lush rows of trees. Northsiders relaxed in limestone restaurants and club rooms after a long day of work. The cost to live in this area precluded many newcomers, primarily African Americans and immigrants, from settling there. They instead lived on the Southside, often in tarpaper shacks, tents, and barracks that lacked ventilation. Lane noted that because the Gary Land Company largely neglected this area, landlords “took advantage of the housing shortage and absence of health regulations or building codes by charging inflated rents and selling property under fraudulent liens.” This marshy region, deemed the “Patch,” attracted “mosquitos, and the pestilential outhouses, unpaved alleys, damp cellars, and overcrowded dwellings were breeding grounds for typhoid, malaria, and tuberculosis.”

Lane noted that immigrant families on the Southside organized into “shanty” communities, where they “stuck together but adjusted their old-world lifestyles to new circumstances.” Sometimes various ethnic and racial groups socialized, and even learned from one another, as Black residents taught immigrants English and vice versa. Lacking access to the opportunities and amenities of the Northside, rampant crime and vice arose as “laborers entered the omnipresent bars armed and ready to squeeze a few hours of action into their grim lives.” Segregated from its inception, Gary’s social construction ultimately resulted in its implosion.

In the burgeoning metropolis, the aforementioned First Methodist congregation met in local schools, businesses, and an abandoned factory before constructing a church on the corner of Adams Street and Seventh Avenue in 1912. With rapid socioeconomic and demographic change taking place in Gary, the church, under the vision of white pastor William Grant Seaman, initiated plans in 1917 to move into the heart of the city. A native of Wakarusa, Indiana, Seaman earned his B.A. from DePauw University and his Ph.D. from Boston University. After ministering and teaching in various states, the pragmatic pastor relocated to Steel City in 1916 at the request of Chicago Bishop Thomas Nicholson.

Seaman, nicknamed “Sunny Jim” for his disposition, contended that Gary’s Methodist church had an obligation to ease the challenges faced by the:

industrial worker . . . often suffering injustice;

the foreigners within our boundaries . . . They represent some fifty different race and language groups;

our brothers in black, coming from the Southland in a continuous stream;

our own white Americans, who come in large numbers from the village and the farm.

He noted that this ministry was especially important, given that many urban churches had relocated to Gary’s outskirts as the city grew more congested. According to historian James W. Lewis, Reverend Seaman felt “the modern city was plagued by a breakdown of traditional community and social control, resulting in an anonymous, mobile, materialistic, hedonistic population.” He therefore believed that it was the church’s responsibility “to develop programs which would provide some of the support, guidance, and satisfaction characteristic of traditional communities.”

Compassionate and industrious, Seaman felt called to meet the “religious and creature-comfort need[s]” of the laborers and their families who poured “in great human streams through the gates of these mills.” However, his beliefs about the city’s newcomers, particularly the African American population, are problematic by today’s standards. He felt that white church leaders were best qualified to uplift the growing Black population, writing in 1920 that “colored people are very ignorant, and to a surprising degree morally undeveloped, and this fact is true of a very large number of their preachers.” Seaman justified the need for white leadership by citing rumors that Black-led denominations “are cultivating in their people a sense of being wronged.” Like Gary’s Stewart Settlement House (on which he served as a board member), Seaman’s intentions seem two-fold: to implement social control in a diversifying city and to provide humanitarian aid.

Lewis noted of Seaman and other white leaders:

Although their perception of the cause was often flawed and their service of it often mixed with other motives, their actions revealed their conviction that the church should be a prominent force for good, even in the modern city.

While Seaman held a paternalistic view of the Black community, his efforts to combat racism drew the ire of the Ku Klux Klan. Seaman opposed showing the film Birth of a Nation, which reinforced stereotypes about the supposed inherent savagery of African Americans. He also tried unsuccessfully to convince the Methodist Hospital to admit Black patients.

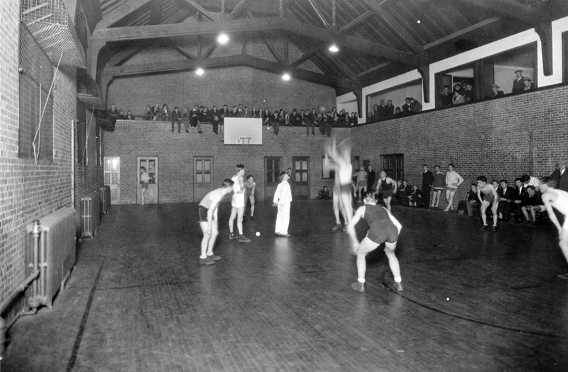

The ambitious pastor quickly got to work, meeting with leaders of the Centenary of Methodist Missions and the U.S. Steel Corporation to drum up support for a downtown church. His lobbying paid off and both groups donated approximately $350,000 to build an “oasis” that would be open seven days a week. In October 1926, Seaman’s vision was realized when City Church—as the First Methodist Episcopal’s downtown church came to be called—opened to much fanfare. Reporters marveled at the ornate cathedral, which boasted of a social-educational unit, gymnasium, rooftop garden, tennis court, and community hall equipped with a “moving picture outfit” and modern stage. It also contained retail stores and a commercial cafeteria, which generated income for church expenses. This was necessary, Seaman said, because the downtown church ministered to groups having fewer resources with which to support the sanctuary.

Although Sunny Jim sought inclusivity, records indicate that the congregation remained white until the church’s closing. Conspicuously absent from photographs of pews lined with worshippers—hair bobbed and suits pressed—were members of color. While Black residents did not bow their heads in prayer beside white congregants (who likely did not welcome their presence), they did utilize City Church’s amenities. According to Lewis, Seaman was fairly successful in promoting the community hall “‘as a religiously neutral ground for artistic and civic events,’” although “there was little mixing of cultures.”

City Church tried to navigate race relations in a polarized city, to some degree, opening its doors to civic, social, and spiritual gatherings. In 1927, the church hosted a race relations service, in which members and pastors of African American churches Trinity M. E. and First Baptist shared in services. Reverend Seaman delivered the principle address, stating “We shall make no progress toward race union . . . until we view each other as God views us, children of the same Father and brothers all.” After toiling in factories, Swedes, Mexicans, and Croatians gathered at City Church to study, worship, and play. Romanian children, “Americanized” at schools like Froebel, congregated in the church gym to socialize and shoot hoops.

When Reverend Seaman left in 1929 under unclear circumstances, the church turned inward and ministered less frequently to Gary’s immigrant and Black populations, especially during the demanding years of the Great Depression and World War II. Unfortunately, Gary’s Negro YMCA closed and African Americans were the first to be let go at the mills, making churches and relief organizations more crucial than ever. Resentment built among Gary residents as they competed for government support, resulting in the voluntary and forced repatriation of Mexican workers on relief rolls. The church did offer programs where weary (likely white) residents could momentarily forget their troubles, hosting Gary Civic Theater plays and an opera by a renowned singer.

Church records from the early Atomic Era denote renewed interest in ministering to the church’s diverse neighbors. The degree to which the church took action is unclear, although advertisements for Race Relations Sunday indicate some walking of the talk.* City Church photographs document an immunization clinic, which served both African American and white children, as well as cooking classes for Spanish girls. It is clear, however, that, despite the efforts of some City Church pastors, members of the white congregation largely did not support, and sometimes opposed, integrated Sunday mornings. With Steel City’s influx of African Americans and immigrants in the 1950s and 1960s, Gary’s white population fled to the suburbs, depleting the urban core of tax revenue. City Church members belonged to this exodus. Tellingly, on a 1964 survey, Rev. Allen D. Byrne appears to have checked, only to erase, a box noting that the church ministered to racial groups.

This changed temporarily with the leadership of Reverend S. Walton Cole, who perhaps came closest to fulfilling Reverend Seaman’s mission, with his 1964 appointment. Cole wrote frequently in City Church’s newsletter, Tower Talk, about confronting one’s personal prejudices and the role of the church in integrating minority groups. Unafraid to confront social issues, Cole argued at a Methodist Federation meeting, “We are not socialists and communists when we talk about moral problems in our nation. Wouldn’t Jesus talk about poverty if he walked among us today?” Under Cole’s pastorship, the church hired Aurora Del Pozo to work with Gary’s Spanish-speaking population. Such efforts, Tower Talk reported, went a long way in understanding their Hispanic neighbors, noting “we were introduced to the viewpoints and attitudes held by these Spanish speaking people that were a surprise to most of us.”

Cole, addressing the trend of church members to “shut their ears and eyes” and move out of the city, noted in 1966:

Hate is the strongest of all. We hate the Negroes, the Puerto Ricans, the Mexicans, the Irish, the English, the Germans, the French. We hate the Jews, the Catholics, the Baptists, the Methodists, the Presbyterians, the Republicans, the Democrats, the Socialists. We hate everybody, including ourselves. This is the way of the world, the secular world.

He countered that the Christian way centered around demonstrating love and hope for all. The NAACP awarded Reverend Cole with the first Roy Wilkins award for his work in civil rights. During his pastorship, the church worked to redevelop the downtown area, striving to “maintain a peaceful and developing community by improving race relations.” But this same year, fugitive James Earl Ray assassinated Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, setting off a string of riots across the country. Riots in Gary’s Midtown section, formerly the Patch, that summer resulted in gunfire, looting, and burning. Gary’s first African American mayor, Richard Hatcher, contended “‘slum conditions in the city and inequalities in education and employment have fostered the tenseness'” that led to the riots.

Some of Gary’s African American residents got involved in the Black Power Movement, which arose after decades of educational, political, and housing discrimination. The movement espoused racial pride, social equality, and political representation through artistic expression and social (and sometimes violent) protest. In 1972, Gary hosted the National Black Political Convention, which drew over 10,000 Americans of color. State delegates and attendees—comprised of Black Panthers, Socialists, Democrats, Republicans, and Nationalists—hoped to craft a cohesive political strategy to advance Black civil rights. This event highlighted Gary’s polarization along racial lines, which became so profound that City Church reported in the 1970s: “Evening sessions are difficult without police protection. Most folks are afraid to come downtown.” This schism was perhaps inevitable, given that city planners constructed Gary around the color of residents’ skin. As City Church membership sharply declined, church leaders realized they needed to build meaningful relationships with the local community.

It became apparent they had waited too long. The 1973 Pastor’s Report to the Administrative Board noted:

Most residents in the immediate area will already have found a convenient church where they are welcome . . . Furthermore Blacks are not likely to come to a church which they ‘feel’ has excluded them for several years. The neighborhood may have continued to change from one social class group to another, so that there is an almost unbridgeable gap between the white congregation and the persons living in the community.

A survey of urban church leaders cautioned in 1966 that, regardless of resources or mission, a white church in a Black neighborhood could only carry on for so long, that the “ultimate end is the same. THE CHURCH DIES!” City Church leaders considered merging with a local Black church, but when community interviews revealed that minority groups did not trust the church, leaders decided to close in 1975. Die it DID.

After decades of decomposition, philanthropic organizations and city leaders have turned their attention to redeveloping the building. After all, as Professor Dotson warns, Gary is in jeopardy of the “eminent collapse under the weight of its own history.” As of now, the most likely outcome involves stabilizing the building and converting it into a ruins garden. A supporter of the ruins concept, Knight Foundation’s Lilly Weinberg, seemingly invokes Reverend Seaman with her statement that “Creating spaces for Gary’s residents to meet and connect across backgrounds and income levels is essential to community building.” Some in Gary oppose this plan, arguing that if the city receives funding it should be allocated to existing African American churches that need structural support, rather than one that ultimately abandoned the Black community.

Regardless of City Church’s fate, Ball State Professor Olon Dotson argues it is crucial that Gary’s legacy of segregation is incorporated into its story “for the sake of the young children, attending 21st Century Charter School at Gary, who look out their classroom windows, or wait for their parents every day, in front of the abandoned ruins of a church, in the midst of abandoned Fourth World space.” If the ruins embody Gary’s past, what is done with them now could signify Steel City’s future.

For a list of sources used and historical marker text for City Church, click here.

* Without the digitization of Gary newspapers, and given the lack of documentation of Gary’s Black residents during the period, it is difficult to give voice to those City Church attempted to reach. Pastor Floyd Blake noted in 1973 that the church conducted over 100 interviews with Black, white, and Spanish-speaking residents regarding their perception of City Church. Although we have been unable to uncover them, they could provide great insight. Please contact npoletika@library.in.gov if you are aware of their location.