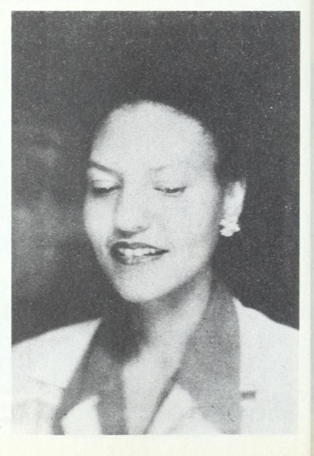

Gary American editor Edwina H. Whitlock wrote in the California Eagle in 1961, “I might perhaps be forgiven for posing as a political authority, but those who know Indiana must acknowledge that basketball and politics are monkeys on the backs of every Hoosier.”[1] The life of Edwina Whitlock, the first and only female editor of the Gary American, is a story that evokes critical insights into the most influential periods in Black history and showcases Black women’s dedication to the long Civil Rights Movement. Whitlock illuminated the rise of the “Black bourgeoisie” and their advocacy for equal rights between the 1920s and into the 1980s, herself having grown up among the small community of Black elites in Charleston, South Carolina. She witnessed the vibrancy of the Harlem Renaissance through her adopted father, strove to emulate W.E.B. DuBois’s ideals regarding Black excellence, and utilized her class privilege to advocate for civil rights and equality through journalism and activism.

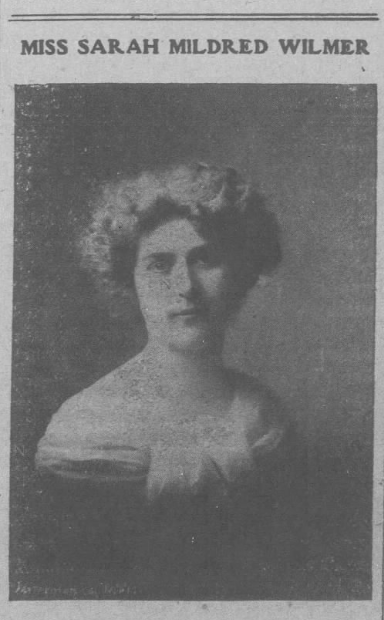

The Early Life of Edwina (Harleston) Whitlock

The Black side of the Harleston family held deep roots within the American South, which defined early on by issues of race and class. Edwina Harleston Whitlock’s ancestors were enslaved. Her maternal great-grandmother Kate Wilson lived in bondage and bore eight of the plantation owner’s children. Harleston never married, and upon his death in 1835, the mixed-race Harleston children, who were denied their inheritance, were pushed back into Black society, and refused inheritance from white relatives. Despite these circumstances, the Harleston’s blossomed in the Jim Crow South, utilizing their status as “mixed-race” in order to toe the line of segregation to make a name for themselves.[2] Together, the family integrated into the small, middle-class population of Black Elites in Charleston, South Carolina.

Originally named Gussie Harleston, Edwina was born in Charleston on September 28, 1916, to Kate Wilson’s grandson, Robert O. Harleston and his wife, Marie Forrest. When she was just two and half years old, Edwina and her sister Slyvia were sent to live with their uncle, Edwin A. “Teddy” Harleston, after their parent’s contracted tuberculosis.[3] However, after the passing of both their parents, the girls were adopted by Teddy and Elise so they could raise them as their own. Teddy Harleston proved to be an inspiring innovator to the girls. As a young boy at the Avery Normal Institute, Teddy developed an interest in painting portraiture and scenes associated with Southern Black culture, which would define his career for the remainder of his life. He went on to attend Atlanta University, where he studied under Black sociologist and activist W.E.B Du Bois.[4] Du Bois and Harleston became life-long friends, and he encouraged Teddy to use his elite social standing to precipitate equality.

Du Bois’s influence permeated the Harleston family. Later in adulthood, Edwina Harleston describes that the family reared their children according to Du Bois’s theory of the “talented tenth,” a concept that emphasized the necessity of higher education to develop the leadership skills among the “most able 10 percent of Black Americans.”[5] They also instilled a work ethic in their children, reflecting Booker T. Washington’s theory that “African-Americans must concentrate on educating themselves, learning useful trades, and investing in their own business.”[6] She contributed her success to these two ideologies, and what ultimately led to Harleston’s academic drive and early involvement in journalism and newspapers.

As a young girl, Gussie’s uncle, Reverend Daniel J. Jenkins, ensured that she was always working in some capacity at the orphanage that he ran in Charleston with his wife, Eloise “Ella” Harleston. She recalls that she had a choice: work on the orphanage farm and dig sweet potatoes, or work on the orphanage’s newsletter, The Messenger. She wrote local updates, which spearheaded her interest in journalism.[7] Harleston began calling up different people and groups– churches, community leaders, and businessmen – to ask them questions about their daily activities so she could write up reports regarding what was going on around town. Tragedy struck in 1931, when Edwin “Teddy” Harleston passed away at the young age of forty-nine.[8] To honor these men, fifteen-year-old Gussie Harleston changed her first name to Edwina.

As a high school student, Edwina Harleston remained a veteran writer for The Messenger.[9] During the height of the Great Depression, Harleston’s familial wealth offered her the rare opportunity to attend a university. In 1934, she went on to attend Talladega College, an HBCU, where nearly “all of the students came from light-skinned African American families in urban centers.”[10] Historian Joy Ann Williamson-Lott explained that, for many Black Americans at this time, advanced study at Black institutions remained rare. However, these environments provided a rich opportunity for Black scholars to educate themselves. Edwina was a part of an emerging generation of educated Black Americans, dubbed “The New Negro,” which celebrated Black history, life, and culture through educational advancement.[11] She majored in English literature, taking classes in Chaucer and Shakespeare, while becoming president of her sorority Delta Sigma Theta. She maintained an active social life in school, even forming a secret society with other young women called Sacred Order of Ancient Pigs (SOAP), where the members got together on slow school nights to

gossip.[12]

It was through this group that Harleston met A’Lelia Ransom, daughter of Indianapolis lawyer Freeman Briley Ransom (better known as F.B.).[13] Ransom’s father served as legal counsel to Madame C. J. Walker and her company. A’Lelia and Edwina became great friends, making their own secret club called “Ain’t-Got-Nothing Club.” Every week, A’Lelia’s father would send the girls newspaper clippings from Indianapolis, along with a dollar or two, and they would read the news and spend A’Lelia’s allowance.[14] A’Lelia Ransom would later become the last president of Walker Manufacturing in 1953.[15]

Harleston graduated from Talladega in 1939 and upon her mother’s suggestion applied to Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. By the fall of 1940, after spending her whole life in the South, she moved to Chicago to attend graduate school, working towards a master’s degree in journalism. Harleston reveals that this was her first time encountering real racism:

In Charleston, I had been sheltered from it, because the white world and the black world were parallel, never touching. Then I got to Northwestern, the so-called great Methodist Institution. Two things happened that surprised me. The star football player, who was black, was meeting the requirements of his major, but he was not allowed to swim in the university pool. . . . There was also the policy of this supposedly religious university that prevented black students from living in the dormitories on campus. . . . Once I was studying for finals with a friend who wasn’t black. I was invited to her dorm room, but at midnight was told by the matron I had to leave because I was colored. I was frightened and furious and had to stumble back across the railroad tracks to my room at the minister’s house.[16]

Northern racism became a constant obstacle and prominent topic of discussion in her work as a female journalist.

While working towards her master’s degree, Harleston worked as a reporter and editor for the Chicago Defender and the Negro Digest. Her experience in writing for newspapers would play a critical role in the next seventeen years of her life. After meeting Henry Oliver Whitlock at Northwestern, the couple married in April of 1945 and Whitlock found herself moving to the booming, deeply segregated City of Gary, Indiana. A year earlier, Henry had taken over operations of his father’s newspaper, the Gary American – one of the largest Black newspapers in Northwest Indiana. By 1947, Edwina Whitlock would appear on the masthead as Lead Editor as the couple oversaw the dissemination of the publication.

The Gary American: Northwest Indiana’s Early Guardian of Northern Equality

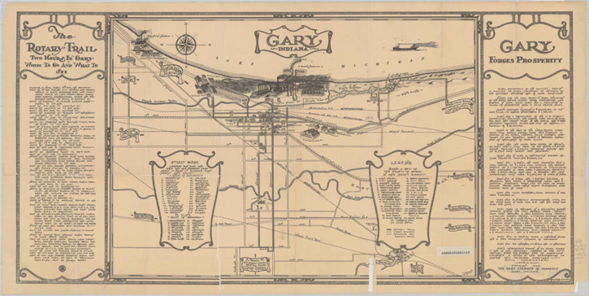

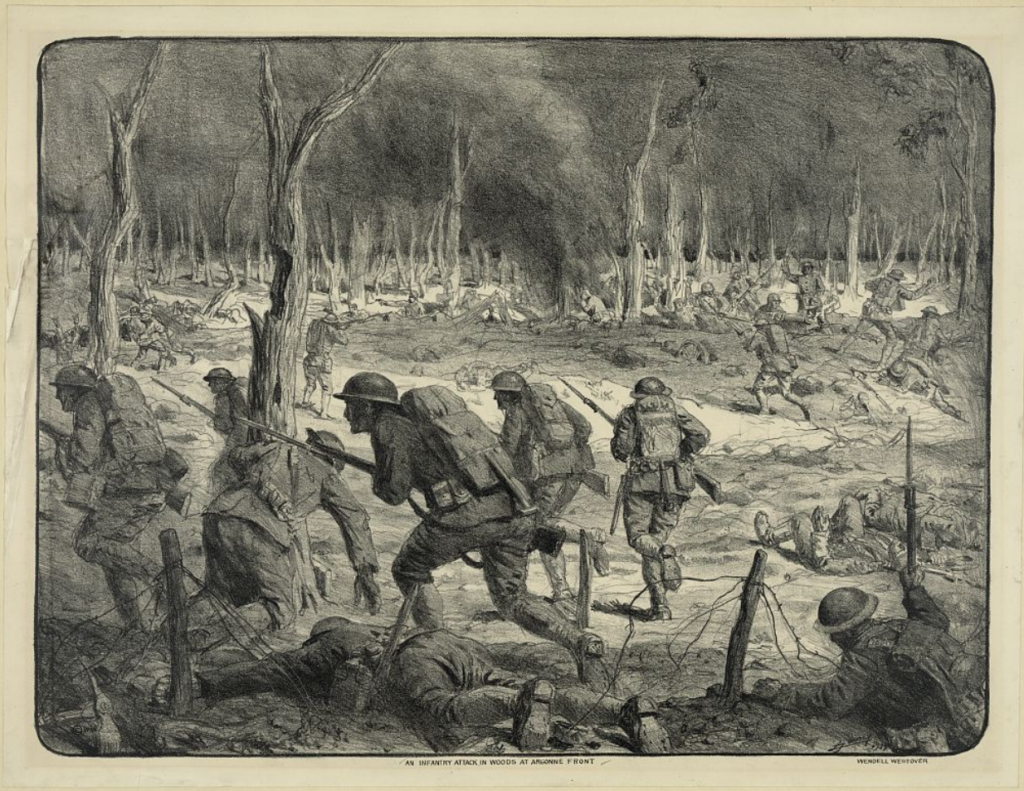

Forty-five minutes from the southside of Chicago and situated next the sandy beaches of Lake Michigan, the United States Steel Company built Gary’s foundations in 1906. Other businesses followed suit. Between 1910 and 1920, Gary’s population jumped from 16,802 to over 55,000.[17] Gary garnered attention, earning the nickname the “Magic City,” as Eastern and Southern Europeans flocked to the area for industrial jobs. However, World War I largely disrupted European migration, and steel companies turned to the Southern portion of the U.S. for labor. The resulting Great Migration drew Black Southerners to Gary’s mills, where they were paid disproportionately low wages.[18]

The influx of Black residents in Gary did not go unnoticed by whites, especially those returning home from World War I to find their jobs had been “taken over” by Black Southerners. In fact, 1920s Indiana was a hotbed for Ku Klux Klan activity, with approximately 300,000 members.[19] Valparaiso, Indiana – only 30 minutes from Gary – became a center for Klan activity in the Northwest region, with the Klan nearly purchasing Valparaiso University (then Valparaiso College). Racism and terror within the region, coupled with the growing Black population, culminated in the creation of the Gary’s own Black newspaper. The publication would disseminate Black news and highlight instances of inequality that did not appear in mainstream publications. In 1927, Arthur B. Whitlock, David E. Taylor, and Chauncey Townsend headed the formation of the Gary American Publishing Company. On November 10, 1927, the Gary Colored American began as a weekly African American paper, publishing its first issue with Townsend as editor and Whitlock as manager.

In its first year of publication, the Gary Colored American led reports on the 1927 Emerson School walkout, when white students and parents protested the integration of six Black students into the school. As a result, the school board decided to reinforce existing de facto segregation, transferring the children out of Emerson, and agreeing to build Roosevelt High School, an all-Black school in the Midtown neighborhood. Gary’s Black population remained divided on this issue, with some advocating for total desegregation and others celebrating the decision to create a new school. The Gary Colored American advocated for the construction of Roosevelt High School to serve Gary’s African American children, citing it as an achievement for Black excellence. [20]

In 1928, the Gary Colored American changed its name to the Gary American, quickly becoming one the city’s most prominent Black newspapers, paving the way for publications like the Gary Crusader. While initial circulation numbers are unavailable, in 1928, the Gary American claimed a readership of nearly 2,000 readers. In 1929, its masthead asserted that the Gary American was an “independent paper” devoted to Black interests in Northern Indiana.[21] The paper columns reflected the upsurge of white supremacy in the 1920s and 1930s, culminating in Jim Crow terrorism that plagued Black communities across the U.S. In 1934, the front page of the Gary American showcased an extensive article about the NAACP’s report that approximately 28 known lynchings occurred the previous year in the U.S. This marked nearly a 200% increase in white terror from 1932 to 1933.[22] By the end of that year, the Gary American published a message to readers, stating, “the Negroes of Gary can look only to The Gary American, their own and only newspaper, for all the news primarily of interest to them and concerning their activities,” claiming that they were the servant of Gary’s Negroes during this tumultuous time period.[23]

Editor Arthur Whitlock left the company in 1938 and attorney F. Louis Sperling was elected editor and acting manager. His legal influence filtered through the Gary American as a plethora of articles featured race and legal rulings within in the U.S. criminal justice system. The Gary American drew attention to a Richmond Times-dispatch editorial in 1937 about the federal Anti-Lynching Bill of 1937:

Now that the rest of the week is apparently available for debating the anti-lynching bill, is it too much to hope that the Southern senators will discuss this measure on its merits, instead of consuming days in flamboyant and bombastic posturing, in apostrophies to the fair name of Southern womanhood, in hysterical outbursts concerning the future of Southern civilization? [24]

The bill passed in the House of Representatives, but was held up in the Senate during a filibuster, where First Lady Elanor Roosevelt sat in the Senate Gallery to silently protest those participating in the blockade. Ultimately, the Anti-Lynching Bill failed to pass in the Senate, despite the Gallup poll revealing that nearly three in four Americans (72%) supported anti-lynching legislations and called for it to become a federal crime.[25]

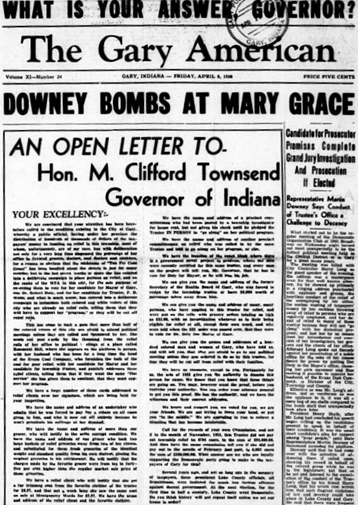

Additionally, in 1938, Editor Sperling released an open letter to Indiana Governor M. Clifford Townsend on the front page of the paper to draw his attention to corruption that was happening within the city. Sperling claimed that a public official, who was responsible for distributing “hundreds of thousands of dollars of the taxpayers’ money” to majority Black families receiving government assistance, was withholding funds to coerce them to vote for her candidate for mayor, Dr. Robert Doty, and for her trustee candidate, P. D. Wells. Sperling wrote, “and what is much worse, [she] has entered into a deliberate campaign to intimidate both colored and white voters of this city who are already on relief rolls, telling them that they will have to support her ‘program’ or be they will be cut off relief rolls.”[26]

Champion of Local Activism and the Civil Rights Movement

In the following decade, the Whitlock’s returned to the Gary American. Arthur’s son, Henry O. Whitlock, became manager in 1944 and his wife, Edwina, becoming editor in 1947. She was a mother and teacher at Froebel High School by day and a journalist by night. The family thrived under the post-war conditions that encouraged a growing middle-class, so much so that they hired a live-in nanny for their children and bought a vacation home in South Haven, Michigan.[27] She saw herself a part of the elusive “Black Bourgeoisie,” which highlighted the white American ideals – Black men worked professional jobs, while the women kept the home with the children. Along with running the Gary American, Henry Whitlock worked as an investigator in the Lake County prosecutor’s office.[28] Following in her adoptive father’s footsteps, Edwina exceeded the realities of Black life, promoting the middle-class lifestyle that many Black Americans lacked, because they did not share her fair skin or generational wealth. But the Gary American gave her unlimited access to disseminate her own ideas about family, Black excellence, and how in Gary’s Black community could fight for self-determination.

During the burgeoning Civil Rights Era, the Gary American focused on issues like discriminatory education funding, the creation of Gary’s first Black Taxicab Company, and the local boycott against Kroger Stores for refusing to hire minority employees.[29] Whitlock published her own column, First Person Singular, for many years. Her editorial topics varied, ranging from marriage and childrearing issues to discussions of race and education. One editorial, appearing in October of 1948, discussed her husband’s opinion that “women dress for other women.” She challenged her readers to question their own partners on the matter to determine if purchasing clothing was self-indulgent as society moved away from the wartime economy and the rationing system.[30] Another editorial, appearing in 1946, was simpler and to the point, “No brains, no hearts – is it any wonder that the Ku Kluxers are also stooges? Right now, they’re stooges for a few racketeers who are clipping them for ten spots or so for the privilege of going around with pillowcases on their heads.”[31] She tackled both the complexities of womanhood and race, offering an intersectional lens to the history of the growing Black population in Gary.

Following World War II, more Black Americans moved to the city, and as a result, they were forced into the central, downtown district, but the city’s boarders grew too slowly to keep up with the expanding population. Rents increased as investments in building repairs dropped, and landlords became virtually unresponsive to Black tenants. By 1940, the U.S. Census reported that only thirty percent of Black families lived in one-family homes, and the remainder lived in apartment houses or small homes converted into apartments, with multiple families living under one unit.[32] Additionally, the Gary Housing Authority – despite its role in maintaining segregated neighborhoods – reported that in 1950, 11,582 families were living in substandard homes or slums, approximately 1,000 more than existed ten years prior to the GHA organizing.[33]

In 1949, she gave birth to the first of four children, whom she raised during her editorial career. That summer, Whitlock addressed her concerns about congestion of the Central District and the strains it imposed on families via poor living conditions and warned about the urge to fall into consumerism rather than focusing on the preservation of the natural world. Her solution was simple – Whitlock proposed an eight-day living week and a thirty-hour work week. She suggested supermarkets offer prepared meals so breadwinners could save money on groceries and utilize the funds for the necessities, like owning a home. Whitlock saw the value in equal payment for all laborers, Black or white, and advocated for the spreading of wealth to relieve the crowded living quarters of the Gary’s Central District. These statements were made during the height of the McCarthy-era, in which rampant persecution of left-wing individuals took center stage of the American political scene. Whitlock did not care. “I sound like a Communist, you say? Well, if Communism means subscribing to a theory that every man’s labor is worth as much as every other man’s,” Whitlock wrote, “having the conviction that the color of a man’s skin should be no deterrent in selecting a place to live – then, come on Revolution. H. O., hand me your shotgun.”[34]

Towards the end of the 1950s, white residents fled to suburban areas like Merrillville due to the city’s increased Black population. Middle-class white families moved away from Gary’s downtown metropolitan center, depleting it of a tax base which thrusted Gary into a state of decline. Black residents, however, were barred from following suit. Once again, housing was featured prominently in Whitlock’s editorials. In 1959, Whitlock discusses her opinions on housing, and the refusal of banks to provide loans to Black locals. Edwina wrote:

Chatted a while today with one of the leading mortgage brokers and I suggested that he and his cohorts could clean up this whole mess with one broad sweep. Instead of refusing to lend money to Negroes who seek better accommodations for themselves by moving to late fringe areas, they should refuse to loan money to the whites who try to run away. If a white family has decent housing in a decent community and the broker suspects that they’re trying to run away from their colored neighbors just let the family do their own financing.[35]

As Edwina pointed out, Black residents struggled to secure access to well-built homes and a welcoming community. However, segregated housing projects were not new – the development could be seen in Gary during the 1930s, and the Gary Housing Authority, established in 1939, continued to segregate residents by placing Black families in the central district, and white families outside of the downtown area.

The Gary American also took a vested interest in the desegregation of the city’s parks, particularly Marquette Beach. Federal programs during the Depression years expanded Gary’s Park system and as a result, U.S. Steel provided the city with a lake-front area. The WPA transformed it into a large park, equipped with a beach, picnic area, and a pavilion. Early editorials reveal how Whitlock felt about lack of community beaches, saying: “But to be continually denied even the elementary right to take a dip in Lake Michigan without having to travel 15 miles to do so, strikes me as being a pretty rotten deal.”[36] In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the city took it’s time when it came to the construction of the new de-segregated section of the beachfront, and many Black residents grew frustrated. Whitlock offered another revolutionary solution: staging a sit-in picnic right on the whites-only beaches. “Getting a few heads bashed in would only be a small price to pay,” Whitlock urged, “for providing our youngsters with an example of forthright action on the part of real men and women.”[37]

Even after Marquette Beach came to fruition, white beachgoers used harassment and violence to keep the sand segregated. However, forced integration occurred only after an uproar in the late 1950s.[38] In fact, Marquette Beach had been a center of white terrorism against local Black beachgoers, with the Gary American reporting in 1949 that a peaceful protest for integration, known as “Beachhead for Democracy,” turned violent when “white hoodlums” hurled bricks, bats, and pipes against vehicles of those who were attending the protest. Police arrived twenty minutes later, closing the beach to demonstrators, which caused the white attackers to disperse.[39] However, the Gary American reported that the protest fueled KKK activity for the next three nights – with white residents burning crosses on the shores of Marquette beach, attacking the homes of “ring leaders” with rocks, bricks, and firing holes into windows with guns, even leaving notes telling residents to leave town.[40]

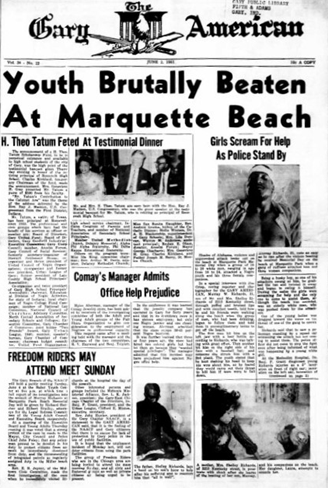

The protests led to the desegregation of Marquette Beach Marquette Beach remained a contentious site. In the summer of 1961, the Gary American produced extensive coverage over the beating of 21-year-old Murray W. Richards. On Memorial Day, Richards and three female friends were enjoying their time at the beach, when fifteen to twenty drunk white men approached the group and demanded that Murray and his friends leave the beach. After refusing, they attacked Richards unprovoked, hitting him in the jaw with a beer bottle, bashing his face with a baseball bat, and striking him with 2×4 plank. One of the young ladies was dragged toward the water under the threat that the gang of men would drown her. Richards explained to the American that “he feared they would carry out their threat to kill him if he were to fall down.” It was revealed that Richards saw one policeman, Officer George Stimple, standing by his squad car, watching the attack, but did nothing to stop it, even after being informed of what was happening by a young white girl.

Richards was left with lacerations on both ears and his scalp, fractures in his jaw and skull, and multiple contusions on his face, arms, chest and back which needed stitches.[41] Only one of his attackers was taken into custody and prosecuted. The beating fueled unrest across Gary, with the paper reporting that more than 500 citizens packed the Council Chambers on June 6, protesting the inaction of Officer Stimple. Charles Ross, First Vice President of the NAACP, stated that the police department had consciously and deliberately refused to provide the minimum protect to Gary’s Black citizens.[42] The protest led to an investigation into Officer Stimple, but on July 7, the Gary American reported that, after a five-hour hearing, Stimple was found innocent by the civil service commission on the charges that he failed to aid Murray Richards. Commission secretary Thomas G. Kennedy claimed, “The evidence presented in support of the charges was inconclusive.”[43] A little over a month later, the Gary American reported on another white attack against Black citizens at Marquette.[44]

Exposing and challenging racism in Northwest Indiana became the goal for Whitlock and her husband. In an interview with Edward Ball, an American author who focuses on history and biography, she recalled just how influential the Gary American was when it came to dismantling segregation in her community:

The American was a local paper, and we fought to get black bus drivers in Gary, when there were none. We fought the electric utility to hire black women because they didn’t have any. Henry’s father, who started the paper, was on the board of the Urban League, and tried to get certain jobs in the steel mills opened to Negroes, because not all of them were. All our circle and all our friends belonged to the NAACP and attended annual meetings.[45]

The Gary American never reached the status of the Chicago Defender, which was in production less than an hour away, but its influence within The Region was wholly felt.

Living History

Henry Whitlock died on May 5, 1960, and the Gary American announced his death on May 13, saying “Henry Oliver Whitlock . . . gave his all to the community. He was for modern, efficient government. He was for the complete integration of Negroes into all facets of American life.”[46] Edwina continued to run the Gary American by herself until February of 1961, when she sold the publication to Edward “Doc” James and James T. Harris, Jr. The Gary American continued to operate until the 1990s, and even expanded its publication beyond Gary into East Chicago/Indiana Harbor.[47]

That same year, Whitlock moved south of Los Angeles with her four children on the edge of Watts, a predominately Black neighborhood that had been isolated from white California. The area faced intense poverty and inequality. Whitlock took on a job in public relations at Watts Savings & Loans. But in August of 1965, Whitlock found her family thrusted into turmoil when the Watts Uprising gripped the neighborhood. Stepbrothers Marquette and Ronald Frye were pulled over right outside their house by a white California Highway Patrol officer while driving their mother’s car, where Marquette was arrested after failing a sobriety test. Back up was called from the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), and a crowd of Black locals formed and watched the arrest unfold, causing one officer to pull his gun out. As a result, Frye’s mother, who witnessed the event unfold outside her house, went to defend her son. All three were arrested, enraging the residents of Watts, who took to the streets to protest police profiling and the conditions of their neighborhood.[48]

Between August 11 and 16, Black residents engaged in a massive protest, confronting the LAPD and taking items from local stores to acquire the goods they were often unable to afford due to pay disparities. In the end, the United States dispatched in 14,000 National Guard troops to Watts, forcing protesters back into their homes. The movement took thirty-four lives and led to over 4,000 arrests. For Whitlock, however, the uprising only motivated her get back into the community, and she quit her banking job to train as a social worker. She told biographer Edward Ball, “I studied for the ‘War on Poverty,’ which is what the Lyndon Johnson administration called it. I guess I was one of those advanced soldiers in the war . . . they were idealists, and we all believed in what President Johnson promised about finding jobs for Blacks.”[49] After passing the civil service exam, Whitlock became a social worker, traveling throughout the city into both Black and white neighborhoods to help families less privileged than her. Along with her new career, she continued her work in journalism with articles appearing in publications like the California Eagle.[50]

By the end of Whitlock’s life, encountered her long-lost cousin, white author Edward Ball, that she finally got the opportunity to tell the world about her family’s contributions to Black history.[51] After an extensive interview process, combing through letters and photographs and outlining her family lore, Ball and Edwina worked together to publish The Sweet Hell Inside: The Rise of an Elite Black Family in the Segregated South in 2001. One year later, Edwina passed away Atlanta, Georgia in November of 2002, at the age of eight-six.[52] Edwina Whitlock’s dedication to highlighting issues of inequality illuminates many of the forgotten Black women at the heart of the long Civil Rights Movement. Through her work as a journalist and her continuous involvement in her community, she utilized her own privilege to promote and sustain equality. The Gary American will soon be digitized and incorporated into the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America database and IHB’s own Hoosier State Chronicles, to give historians the chance to uncover Northwest Indiana’s often discounted, but rich Black history and unveil more stories like Edwina Harleston Whitlock’s.

Notes:

[1] Edwina H. Whitlock, “Gary, Ind., Negroes Help Run City Gov’t,” California Eagle, October 19, 1961, accessed Newspapers.com.

[2] William’s and Kate’s son, Edwin G. “Captain” Harleston proved to be an American pioneer, establishing a successful funeral business that allowed his five children to thrive. His son, Edwin A. “Teddy” Harleston, became a successful painter and renowned portraitist. Another son ran an orphanage, whose young Black children became musical prodigies in the group Jenkins Orphanage Band.

[3] Robert Harleston and Edwin A. “Teddy” Harleston were two of Edwin “Captain” Harleston’s seven children. Captain Harleston was Kate Wilson’s fifth child with white plantation owner, William Harleston. In Charleston, Captain ran a profitable funeral business that serviced the Black community.

[4] E. Rudwick, “W.E.B. Du Bois,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed Brtannica.com.

[5] Edward Ball, The Sweet Hell Inside: The Rise of an Elite Black Family in the Segregated South, New York, HarperCollins Publishers, 2002, 297, accessed Internet Archive.

[6] “Booker T. Washington,” Teach Democracy, accessed crf-usa.org; Ball, The Sweet Hell Inside, 297.

[7] Ball, The Sweet Hell Inside, 297- 298.

[8] Teddy’s father, Captain Harleston, died in April of 1931, after catching pneumonia. A few days after his father’s funeral, Teddy caught pneumonia as well. Later in her life, Edwina recounted to Edward Ball that the doctor reported that Teddy had a good chance of recovery. However, the grief of losing his father superseded his will to fight the infection. Teddy Harleston passed one month later, on May 10th, 1931; [8] Ball, The Sweet Hell Inside, 286-287, accessed Internet Archive

[9] Edwina was also a singer in the Avery glee club and president of her high school class; Ibid, 298.

[10] Ibid, 303.

[11] Joy Ann Williamson-Lott, Jim Crow Campus: Higher Education and the Struggle for a New Southern Social Order (New York: Teachers College Press, 2018), p. 21-22, accessed Google Books.

[12] Ball, The Sweet Hell Inside, 308.

[13] “Freeman Briley Ransom,” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, accessed indyencyclopedia.org.

[14] Ball, The Sweet Hell Inside, 308-309.

[15] Douglas Martin, “A’Lelia Nelson, 92, President Of a Black Cosmetics Company,” The New York Times, February 14, 2001, accessed The New York Times; “Mrs. Nelson Heads Madam Walker Firm,” The Indianapolis News, February 10, 1951, accessed Newspapers.com.

[16] Ball, The Sweet Hell Inside, 319-320.

[17] “Indiana City/Town Census Counts, 1900 to 2020,” StatsIndiana: Indiana’s Public Data Utility, accessed https://www.stats.indiana.edu/population/PopTotals/historic_counts_cities.asp; Ball, The Sweet Hell Inside, 328.

[18] Neil Bretten and Raymond A. Mohl, “The Evolution of Racism in an Industrial City, 1906-1940: A Case Study of Gary Indiana,” The Journal of Negro History, 59, no. 1 (Jan 1974): 52, accessed https://doi.org/10.2307/2717140.

[19] Ball, The Sweet Hell Inside, 328.

[20] “Lay Foundation For First Unit to Roosevelt School, New Addition Will Be Ready Late in 1930,” The Gary American, July 2, 1929.

[21] The Gary American, April 5, 1929.

[22] “28 People Lynched in 1933, Says NAACP; One Freed by Jury,” The Gary American, January 5, 1934.

[23] “The Gary American Message,” The Gary American, November 30, 1934.

[24] Editorial: “Debating the Lynching Bill,” The Gary American, November 26, 1937.

[25] Justin McCarthy, “Gallup Vault: 72% Support for Anti-Lynching Bill in 1937,” May 11, 2018, accessed Gallup News.

[26] “An Open Letter to Hon. M. Clifford Townsend Governor of Indiana,” The Gary American, April 8, 1938.

[27] Ibid, 331.

[28] “Heart Attack Claims Publisher,” The Times, May 5, 1960, accessed Newspapers.com.

[29] “Pass Up Roosevelt High: Negro School to get No Funds for Facilities,” The Gary American, September 29, 1944; “Negro Taxi-Cab Company in Operation with 3 Cabs, Fleet of Five Cars Expected to be in Service Next Week,” The Gary American, November 23, 1945; “Continue Boycott of Kroger Stores, Attempts to Arbitrate Fail,” The Gary American, October 3, 1958.

[30] Edwina Whitlock, “First Person Singular,” The Gary American, October 8, 1948.

[31] Whitlock, “First Person Singular,” The Gary American, July 26, 1946.

[32] Bretten and Mohl, “The Evolution of Racism,” 59.

[33] Gary Housing Authority, The First Twenty Years: Report of the Gary Housing Authority, 1939-1959, n.d., 14, accessed HathiTrust.

[34] Whitlock, “First Person Singular,” The Gary American, July 1, 1949.

[35] Edwina Whitlock, “First Person Singular,” The Gary American, December 24, 1959.

[36] Whitlock, “First Person Singular,” The Gary American, July 19, 1946.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Gary Housing Authority, The First Twenty Years, 56.

[39] The Gary Post Tribune stated that the demonstration at Marquette Beach seemed “pointless” as there were no legal restrictions against Blacks utilizing the facilities there. This is just one example of the stark differences between white reporting and Black reporting within the city; The Terre Haute Star, August 31, 1949, accessed Newspapers.com.

[40] “Beach Project Leads to Violence: KKK Becomes Active,” The Gary American, September 4, 1949.

[41] “Youth Brutally Beaten at Marquette Beach, Girls Scream for Help as Police Stand By,” The Gary American, June 2, 1961.

[42] “500 Jam-Pack Council; Protest Actions of Police,” The Gary American, June 9, 1961.

[43] “Stimple Found Not Guilty,” The Gary American, July 7, 1961.

[44] “Hoodlums Attack Again At Marquette Park,” The Gary American, August 11, 1961.

[45] Ball, The Sweet Hell Inside, 329-330.

[46] “The Death of Henry Whitlock,” The Gary American, May 13, 1960.

[47] “An Open Letter to 9,000 People,” The Gary American, March 24, 1961.

[48] Casey Nichols, Watts Riot (August 1965), published October, 23, 2007, accessed BlackPast.org.

[49] Ball, The Sweet Hell Inside, 338.

[50] “President John Kennedy, Gov. Pat Brown Electrify 600 Attending Links Inc., Affair,” California Eagle, November 23, 1961, accessed Newspapers.com.

[51] Whitlock’s experience as a journalist spurred a desire to document her rich family history. In 1970, after her daughter Sylvia wrote a term paper on Teddy Harleston, Edwina’s interest in genealogy was re-ignited. She spent years going through the large collection of the Harleston family papers, photographs, and letters. While researching, she attended lectures at institutions like Mann-Simons Cottage to talk about her adoptive mother, Elise Forrest Harleston, one of the first Black female photographers in the US. Whitlock’s goal, however, was to publish her family history.

[52] “Whitlock,” The Atlanta Constitution, November 22, 2002, accessed Newspapers.com.

Many people are looking for ways to channel the anxiety of our current crisis into something healthy and productive. For those of us with green thumbs, this has meant more time in the garden. And there is no better place for us to get some sage advice than from those Hoosier gardeners who came before us. Luckily, some of them shared their wisdom in an early-twentieth century column in the Indianapolis News titled “Of Interest to Farmer and Gardner.”

Many people are looking for ways to channel the anxiety of our current crisis into something healthy and productive. For those of us with green thumbs, this has meant more time in the garden. And there is no better place for us to get some sage advice than from those Hoosier gardeners who came before us. Luckily, some of them shared their wisdom in an early-twentieth century column in the Indianapolis News titled “Of Interest to Farmer and Gardner.”