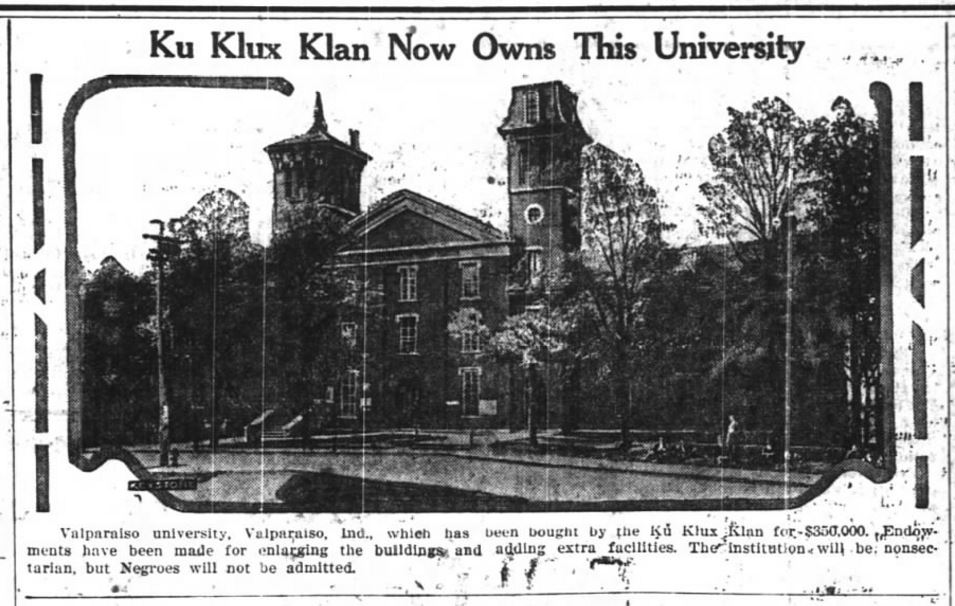

When the Hagerstown Exponent published this headline in October 1923, the editor had slightly exaggerated. The Ku Klux Klan’s powerful “Indiana Realm” had not literally bought itself a venerable institution of higher learning that summer– but it had come close. For a few weeks, Valparaiso University — sixty miles from downtown Chicago and formerly one of the largest private schools in the U.S. — teetered on the brink of becoming a “Ku Klux Kollege.” Once praised as the “Poor Man’s Harvard,” in 1923, many feared the university was about to become a “hooded Harvard.”

“Valpo” is a thriving university today, with some of the best programs in Indiana — and has no connections whatsoever to the KKK. Yet, a century ago, after its rapid rise to national fame, the highly-respected school experienced hard times that took many alumni and faculty by surprise.

Founded by Methodists in 1859, the original school — Valparaiso Male and Female College — took in students of all levels, from elementary to college age. The pioneer school was also one of the few co-educational institutions in America before the Civil War. That war wreaked havoc on enrollment, leading the college to close its doors in 1871. Two years later, it reopened as a teacher’s college. Until 1900, the school went by the name Northern Indiana Normal School and Business Institute.

Renowned for its economical tuition and low cost of living — as well as for admitting women and students from overseas — by 1905 “Old Valpo” enjoyed one of the highest enrollments of any private university in the U.S. With over 5,000 students that year, the school ranked just behind Harvard. Its affordability to working-class Americans led many to praise it as the aforementioned “Poor Man’s Harvard.”

Students from all over the U.S. and the world trained to be public school teachers there. Some were later busy teaching English to immigrants employed at Gary’s new steel mills. Valpo’s programs in law, engineering, medicine, and dentistry were well-regarded. Its College of Medicine and Surgery had been brought over from Northwestern University in Chicago. When the college moved back to the Windy City in 1926, it formed the nucleus of Loyola’s medical program.

Harvard and Yale might have been too good to take out ads in Chicago newspapers. But this ad from 1905 appeared next to one for another great school on the rise, the University of Notre Dame.

Yet, once enrollment peaked in 1907, venerable Valpo plunged into an unexpected, two-decade-long decline. After accreditation of American colleges and universities began at the turn of the century — partly driven by a desire to standardize high-school education and thereby “unify” the country — Valparaiso failed to win accreditation. Suddenly unable to transfer their credits, current and prospective students found the school a harder sell, especially as affordable new state universities, teachers’ colleges, and urban night schools entered the competition. Valpo’s lack of a football team and Greek life were another stumbling block, though it hurriedly scraped together a football program in the early 1920s and even played Harvard. (It lost 22-0 in its first game.)

World War I issued another blow. The famously affordable university had always attracted international students. (One of the more unusual of them was future Soviet Comintern agent Mikhail Borodin, “Stalin’s Man in China,” who would die in a Siberian gulag in 1951.) But after 1914, many of these students left to fight for their European homelands in WWI. When America entered the war against Germany in 1917, student military enlistment left Valpo’s academic and residence halls almost empty. Also, with plenty of war-related jobs now available to women, female students also tended to skip out on college for the duration of the war.

In 1919, Indiana passed a new law requiring private colleges to maintain a half-million dollar endowment. Cash-strapped Valparaiso University, burdened with a $350,000 debt (almost $5 million in today’s money) faced the real prospect of bankruptcy. The school’s trustees even tried to sell it to the state that year for use as a public teacher’s college, but the Indiana legislature declined the offer.

Holding on by a thread — and led by controversial president Daniel Russell Hodgdon, who turned out to hold fake medical degrees — desperate trustees and the equally-desperate citizens of Valparaiso sought new owners. That list of potential “saviors” grew to include the Presbyterian Church, the International Order of the Moose, and the owner of Cook Laboratories in Chicago, who wanted to turn the campus into a syringe factory and provide 1,000 jobs to townsfolk.

Then, in August 1923, a new bidder expressed interest. For some residents of Valparaiso — which hosted a parade of at least 6,000 Klansmen in May 1923 that attracted 50,000 visitors from around the Midwest — the offer from the Ku Klux Klan to take over the struggling school seemed like a God-send. Academics, alumni, and students thought differently, especially Catholics and Jews, and many were ready to pack up and leave. Yet, as far as the trustees were concerned, the question of selling Valparaiso University to the Ku Klux Klan mostly came down to whether that organization itself had the resources to made good on its own offer.

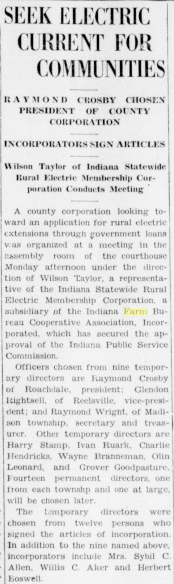

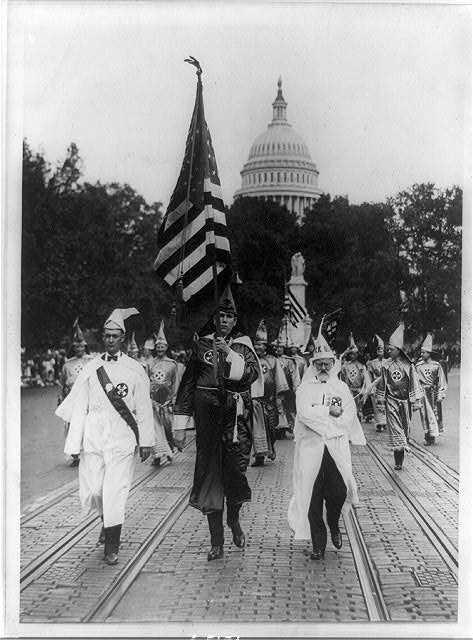

The efforts of the revived Klan proved more durable than that which had died out in the 1870s. Klan rallies and parades occurred all over the North and West, from Chicago and L.A. to Oregon and Maine. KKK membership in those years peaked in Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio, “ground zero” for some of the biggest Klan activity. D.C. Stephenson, the Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan in 23 states, operated mostly out of his headquarters in Indianapolis, a city that was almost taken over by Klansmen and Klanswomen; It was also a city that fought a valiant battle in the press, courts, and churches to discredit the “Invisible Empire.”

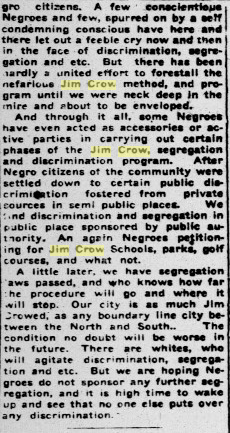

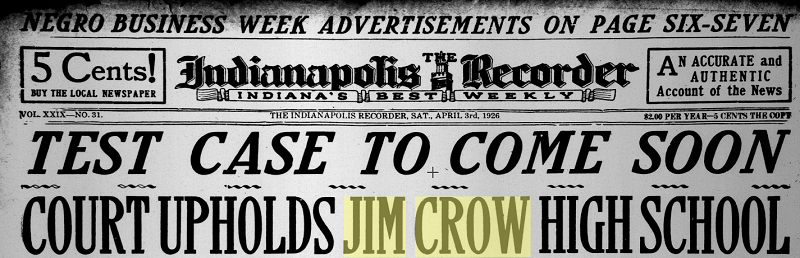

The “second wave” of the Klan defined itself as a hyper-patriotic organization of white Protestant Americans and was more mainstream than at any other point in its history. Instead of waving the Confederate flag at rallies and parades as had previous iterations of the Klan, they flew the red, white, and blue. During the 1920s, the Klan was less concerned with suppressing African Americans than with stemming the tide of new immigration coming from Southern and Eastern Europe — including to heavily-industrial towns like Gary, just thirty miles from Valparaiso. The Klan sought to cripple an imaginary conspiracy contending that Catholics wanted to destroy American public schools and hand the U.S. government over to the Pope. It also warned of the activities of “Jewish Communists” and anarchists in the wake of the Russian Revolution and the 1919 Red Scare. Prohibition of alcohol, another cause taken up by the KKK, was a barely concealed way to crack down on immigrant culture.

These views were shared by thousands of Americans who didn’t belong to the Klan. The “Invisible Empire” even found strange bedfellows in the Progressive movement, including women’s suffrage advocates, who espoused some of the same “reform” ideals promoted by the Klan, albeit with different objectives. They also got involved in public health. In 1925, the organization helped fund a hospital in Logansport that catered only to Protestants. Alongside these initiatives, acquiring a university would have helped the Klan project a more legitimate image. Since Valparaiso was a teacher’s college, the Klan could also propagandize American children from within schools.

By July of 1923, the trustees of Valparaiso University and the Klan were talking. Representing the Klan was Milt Elrod, whom Stephenson had recently made editor of the Fiery Cross, the major KKK newspaper, printed at the Century Building on South Pennsylvania Street in downtown Indianapolis.

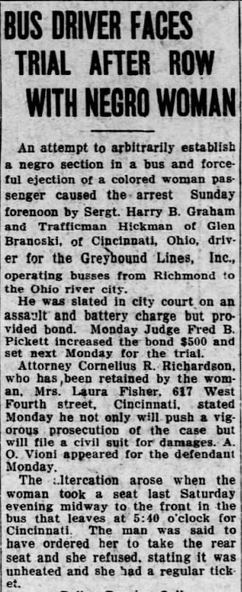

When encountering obvious concern from much of the faculty and student body, Elrod assured the press that a Ku Klux takeover of the school would change nothing except the trustee board, which was to be filled with Klan appointees. The school would remain open to women and would be non-sectarian, Elrod insisted — though Catholic students were already beginning to drop out and enroll elsewhere. Ludicrously, Elrod initially claimed that the Klan would admit any applicant who met the proper educational requirements, including African Americans, though he later admitted that the school would not have adequate facilities for them. (The sad irony is that Valparaiso University did not admit African Americans even before the Klan tried to buy it.)

Few people (trustees excepted, it seems) took Elrod at his word when he said that nothing else would change at the university, except skyrocketing enrollment and the return of its once prestigious reputation. Yet Elrod’s enemies had already come out. In the Fiery Cross on August 24, 1923, he was busy singling out “un-American” and “alien forces” as his opponents. Elrod may have been quick to pick up on campus rumors that Catholic priests from Notre Dame had visited town, spurring the Klan to act soon and not be outbid by the “agents of Rome.”

Heavy opposition came from the press. Even in Indiana, major urban newspapers tended to be anti-Klan, including the Indianapolis Star, Indianapolis News and most famously the Indianapolis Times, which won a Pulitzer for its battle against the group. Some of the sharpest criticism, however, came from George R. Dale, the wildly colorful and energetic editor of the Muncie Post Democrat. Dale, who endured death threats and assaults on his life and that of his family, ran a paper that was virtually one long, rambunctious op-ed piece, employing a folksy humor to give sucker-punches to the powerful “Indiana Realm.” Dale went on to become mayor of Muncie in 1930.

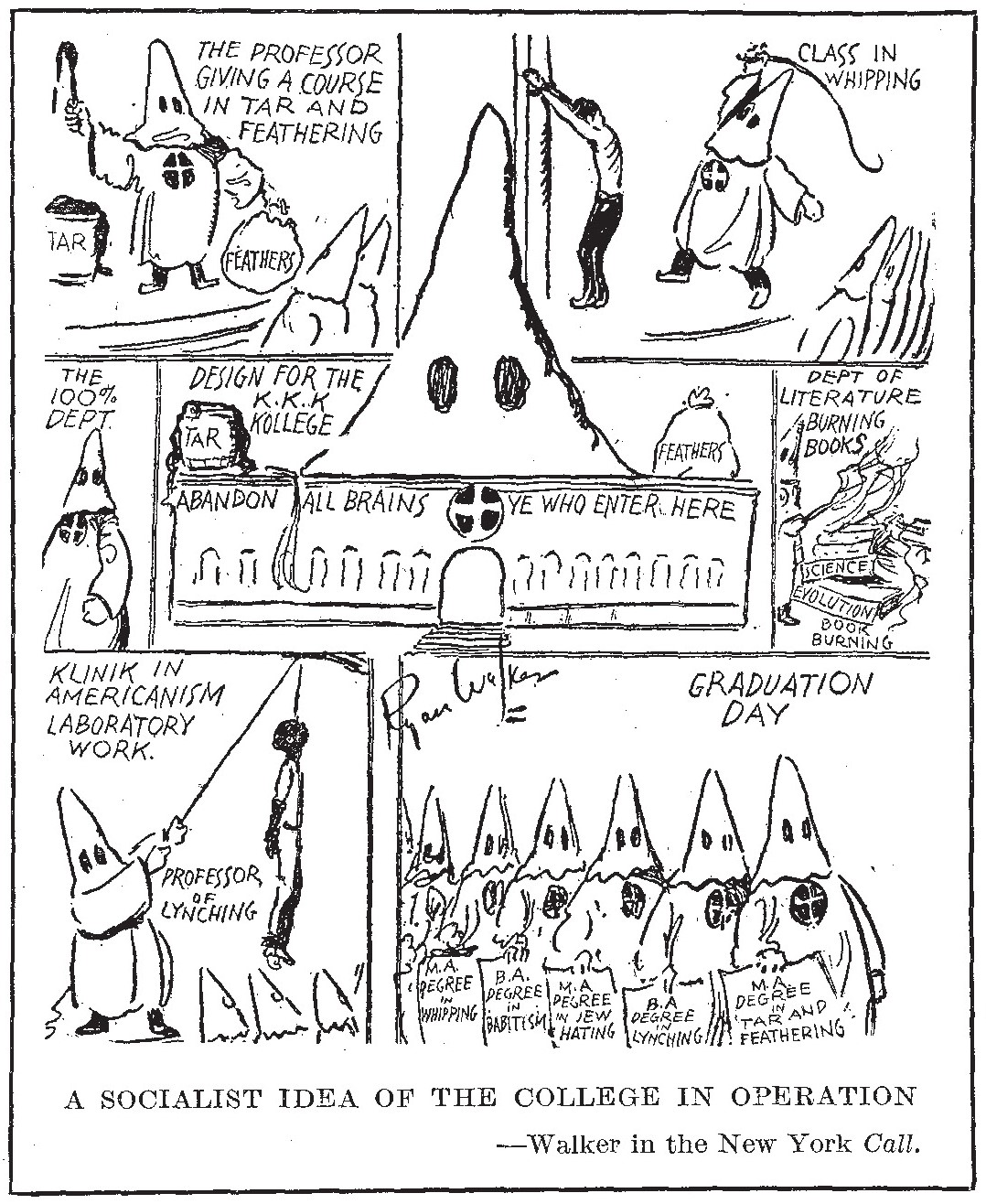

Editors and cartoonists nationwide– including E.H. Pomeroy, an illustrator for the Valparaiso Vidette — tore into Elrod’s proposal once it came out that he might, in fact, get hold of the $350,000 in cash needed to bail the school out of debt. (Elrod also promised that the Klan would set it up on a million-dollar endowment, twice the amount required by Indiana law.) As the story spread across the U.S., an illustrator in the New York Call went straight for the jugular, publishing a parody of Dante’s Inferno — “Abandon All Brains Ye Who Enter Here.” The cartoon depicts book-burning, classes in whipping and tar-and-feathering, a “Klinik” to teach “100% Americanism,” and a commencement day ceremony where students sport an unconventional new style of cap and gown.

Another critical broadside came from Helena, Montana. The writer in Helena’s Independent Record thought that a bout of education for those in the Klan might at least have a few “salutary” side-effects.

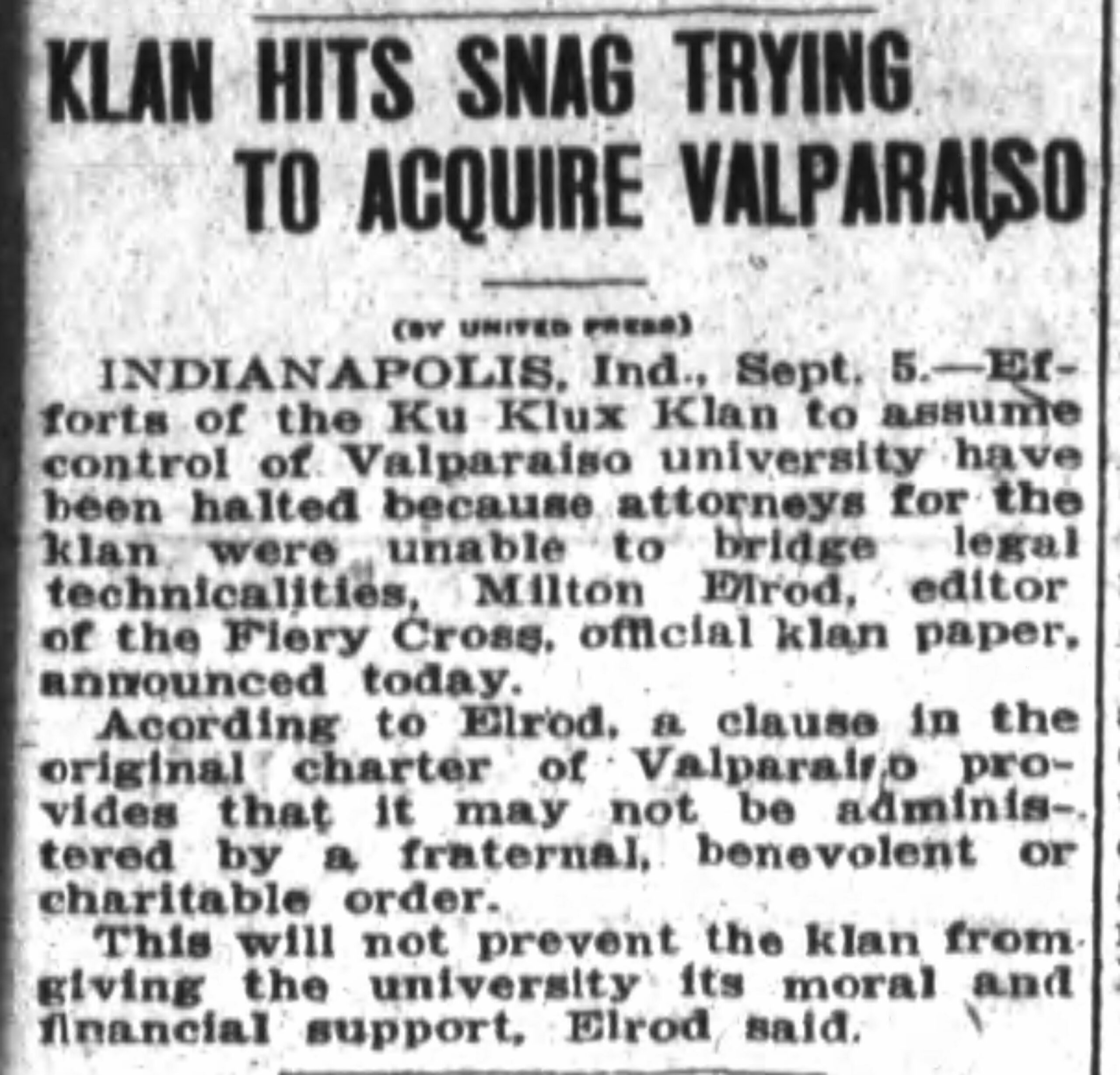

One editorial, “Ku Klux and Kolleges”, appeared in Robert W. Bingham’s Louisville Courier-Journal. It asks if there is no provision in the Indiana school’s original charter to prevent the sale to the Klan. The Courier-Journal also pointed out that many teachers in Kentucky had been trained at Valparaiso in its better days, and that Kentuckians should be concerned about its ultimate fate.

Though excitement among some Valparaiso citizens allegedly ran high, Milt Elrod was probably too quick to make blustery promises about the Klan’s own financial strength. His proposal to buy the school wasn’t completely baseless, but Elrod was a notorious booster and propagandist.

Through the sale of thousands of robes, newspaper subscriptions, and membership fees, the leadership of the Klan had amassed huge fortunes for itself. D.C. Stephenson had gone from being a poor coal dealer in Evansville to a wealthy man by age 33, but he squandered Klan money on liquor, women, cars, and a yacht. Even the $350,000 needed to buy the Valparaiso campus — not to mention the $1,000,000 offered as an endowment — was apparently beyond the ability of the Klan to come up with (or hang onto).

The American press and higher education breathed a sigh of relief when, after just a few weeks, Elrod feebly announced that the Klan had changed its mind due to “legal technicalities.” Some papers reported that — true to the Louisville Courier-Journal’s suggestion — a clause in the school’s original charter had been discovered, preventing control by any “fraternal, benevolent or charitable order” (an inaccurate description of the Klan, at any rate).

“Legal technicalities” caused by the school’s charter might have been a myth, a clever way for both the university and the Klan to save face after the embarrassing episode. Most newspapers ran with it, but there seems to be little evidence that university trustees would have called off the sale if enough cash had been put down in front of them.

Fortunately, Valparaiso University never fell into KKK hands. With the corrupt Klan itself in disarray by 1925, and with Stephenson headed to the nearby state prison at Michigan City for rape and murder, any future Klan bids were out of the question.

In the summer of 1925, the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod rescued the run-down, almost abandoned school. Lutherans at that time had several colleges and seminaries around the U.S., but no university. They announced vague plans to use it as a theology school or teachers’ college. Securing the deal was assisted by Reverend John C. Baur, a Lutheran minister and noted opponent of the Ku Klux Klan in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Under Lutheran guidance, Valparaiso University’s fortunes gradually turned around, though it barely survived the Great Depression. By the 1950s, “Old Valpo” once again ranked among Indiana’s and the nation’s best colleges, a reputation it still holds today.

Hoosier State Chronicles provides searchable access to several years of The Fiery Cross.

Other materials from the Indiana State Library on the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana can be found here.

Contact: staylor336 [AT] gmail.com