Central Indiana abounds in the sites of small towns that have disappeared over the years but still are important to a county’s history. Many of these places only had a rural post office, a railroad stops, and a cluster of houses surrounding a mill or general store. Towns became lost for a variety of reasons. In most cases, the economic activity that supported the town stopped or shifted elsewhere. Perhaps residents abandoned a village because the settlement ceased to offer the same amenities as a nearby community. Sometimes a major transportation avenue, like a railroad, bypassed the town, effectively closing it to the outside. Other towns grew around a post office and when the post office closed, so did the town.

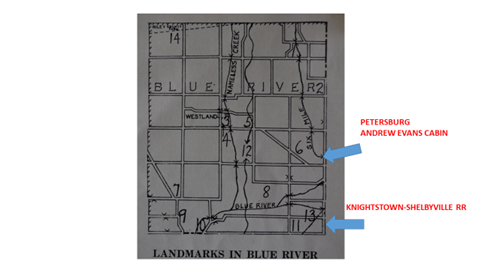

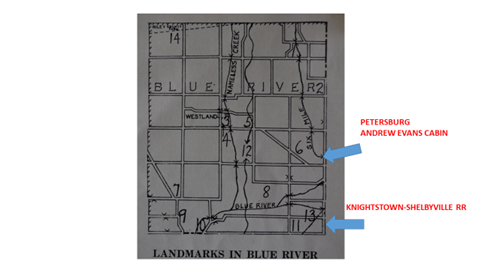

The area that is now called Hancock County was first settled around 1818. Andrew Evans, John Montgomery, and Montgomery McCall came to the area with their families and settled on the Blue River. Evans built the first crude log cabin in 1818 and two years later Elijah Tyner, Harmon Warrum, Joshua Wilson, and John Foster homesteaded on the Blue River. In 1822, Solomon Tyner, John Osborn, and George Penwell with their families also made their home on this historic stream. These families were in the Hancock County before it was organized.

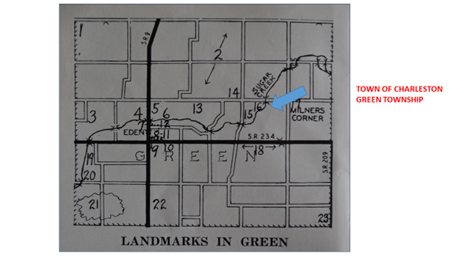

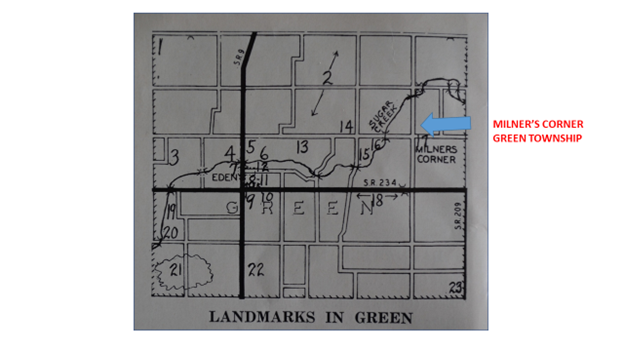

Many early settlers arrived in the Hancock area on the Napoleon Trace, which was an old buffalo trail used by the Delaware and Shawnee. It extended through the current townships of Blue River, Jackson, and Green. The trail crossed the Blue River near Warrum’s old home and Sugar Creek near Squire Hatfield’s at a place known as Stover’s Ford. In the current Green Township, the Napoleon Trace ran close to the proposed Charleston and Milner’s Corner.

According to the Binford History of Hancock County:

When the early settlers came to the Blue River it was a dense wilderness for miles and miles; one save the rustling of the leaves, the moaning of the wind, and the angry voices of storm clouds; no music broke the calm stillness of the summers air save the buzzing of the mosquitoes, the howling of ravenous wolves, or the fierce yell of the prowling panther; no noisy hum of laboring factories; no clanking of hammers in dusty shops.

Settlers had to go as far away as the White River to mill grain at Connersville about 40 miles away. The first blacksmith in the county was in Blue River, Thomas Phillips. Elijah Tyner, on the Blue River, had the first store and orchard in the county.

Small communities in these townships were platted and set up at rural crossroads or streams. They supplied essential goods and services to the settlers like blacksmiths, grain elevators, churches, schools, lawyers, taverns, doctors, post offices, and transportation. Some communities were platted or named on maps but never existed. Others existed and failed because of competition of other nearby settlements, roads that bypassed the community, or the removal of an essential service like the post office. These are the lost towns of Hancock County.

Petersburg

The Knightstown and Shelbyville railroad maintained one stop in Hancock County in Blue River Township called Petersburg. It was located on the county line east of the Handy school house.[1] Petersburg was named for Peter Binford, who erected a log cabin around the station area. The cabin of Andrew Evans, the first settler in Hancock County, was near the vicinity.

Notes on Petersburg appear in the Hancock Democrat newspaper as early as the 1880s, written by an agricultural worker known as “Plow Boy.” The paper reported:

Isaac T. Davis is visiting here. He reports things lively in Blue-River Township. Charles Nibarger is the champion jumper of this place.” In 1895, the paper also delivered the sad news that “A small daughter of Mr. Derring of Petersburg was buried on Tuesday. Services by the Rev. Beckett at the Universal church.

Silas Haskett sold a small lot at Petersburg to John Young for the purpose of running a store and an eating house, which he did for several years. Young sold it to Daniel Haskett who kept a general store at the site until after the railroad went out. The Petersburg Station was a large platform for loading across the county line to Rush County. Captain P.A. Card also ran a store in the Blue River Township after 1872 for several years.[2]

The Knightstown and Shelbyville Railroad accommodated passengers, who could stop the train anywhere along the line by waving a handkerchief. Beginning operation in the 1840s, it crossed the southeast corner of Blue River Township, following the south valley of the Blue River. According to an earlier publication of the Hancock County Historical Society, “This steam railroad said to have been first west of the Alleghenies, ran with a crude wood-burning locomotive and two cars both open. Whenever things went well, the railroad made one trip a day between its terminals. The railroad ran until 1855, after which time, was shut down, the iron rails were salvaged for use in the Civil War.” The old grade still can be seen at some places, such as the current Tyner Pond farm.

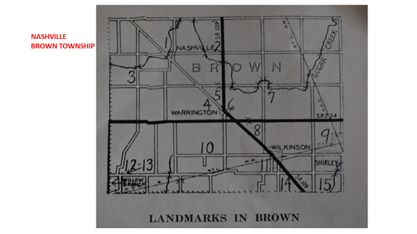

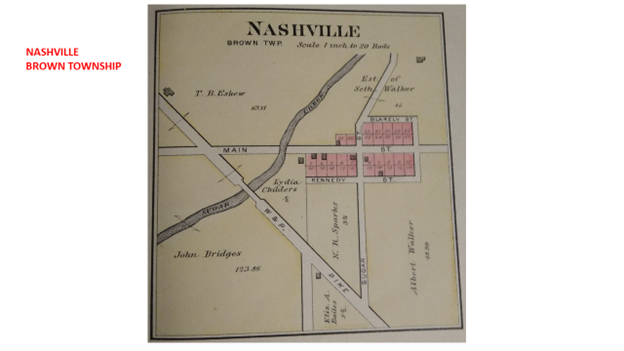

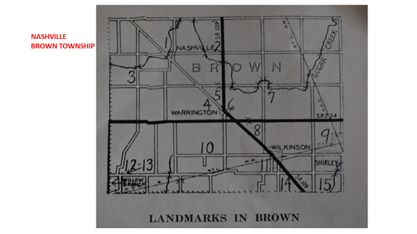

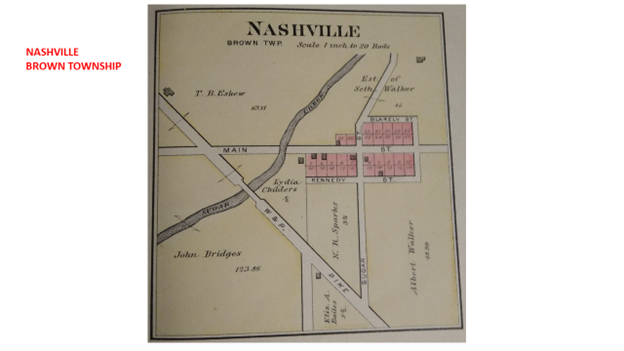

Nashville

Nashville, located in Brown Township, was originally platted by John Kennedy and David Blakely on December 30, 1834.[3] The town was named after the ancestral home of one of the founders. Nashville was located on the Knightstown Pendleton Road, where it crosses the Sugar Creek. Stores and blacksmith shops had long been maintained at the site. Among the early business owners were Elijah Thornburgh and Allen White. By March 1847, the Board of Commissioners granted William L. Davis a license to run a tavern at Nashville. The eventually stores disappeared but the blacksmith shops outlasted the stores for several years. A church which is now a residence, and a few old houses are standing at the site.[4]

The Hancock Democrat reported the following events:

An administrator’s sale on the property of Samuel Griffith’s of Nashville was conducted on December 23, 1870, for all his personal property of 1 horse, cattle, hogs, corn in the fields, wheat, farming tools, household furniture, &c. Terms of the sale was cash.

In February 1891, “Taylor Garriett of Nashville was in our midst last week. He is much improved in health and will be able to do justice to a square meal before long.”

John W. Smith, near Nashville, found a stray hog in November 1891. “Sometime last week I took up a stray hog which the owner can have by describing the same and paying a fair price for his care and this advertisement.”

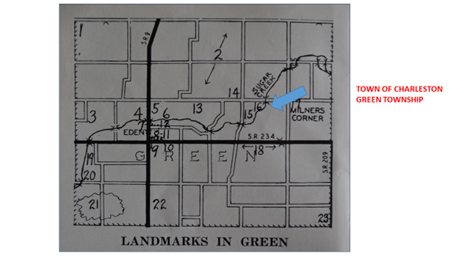

Charleston

Charlestown in Green Township was laid out on the west bank of the Sugar Creek. Charleston appeared in the County Commissioners records in connection with road construction. It was platted but likely never came into existence. Supposedly nothing was ever built at the site. In 1959 local historian Jake Hite says that longtime residents would turn up pieces of dishes, glass and other items when plowing on the Dave Rash Farm north of the old Cook Cemetery. Perhaps in the early days there were a few dwellings erected on the town site.

Berlin

Berlin was platted but never constructed. Located in Center Township, Berlin was laid out by William Curry during the 1830s.[5] It was platted to a gristmill which was running at the time. A note appeared in the Hancock Democrat in February 1885 requesting information on a lost town. Mary Bragg found a note in the county deed records with a reference to the Town of Berlin, but the exact location was not noted. “The town has 51 lots arranged on various sides of a large public square. The man that platted the town evidently believed in education as in every other square is a lot marked ‘school.’

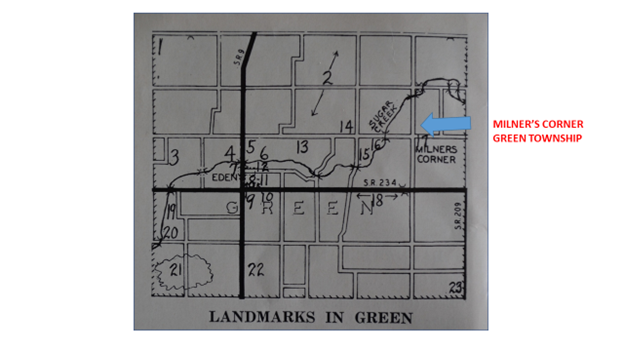

Milner’s Corner

Milner’s Corner was located in Green Township and consisted of one or two dwellings, a store and a blacksmith shop.[6] Beginning in the 1850s, business was conducted at the site for more than one half of a century. Milner’s Corners was named after either James Milner or Henry Milner in 1850. The community was never platted. The first store was kept by David Mckensey, who was a former schoolteacher.[7] The post office was set up in 1868 with the first postmaster being Nimrod Davis. When the post office was set up in the 1860s, it delivered to a population of forty.

The Hancock Democrat reported on the activities of Milner’s Corner frequently. In February 1881, it noted:

A new debating society is in successful operation. Champion debaters were John G. Davis and Oliver Collins; regular jurors were John Collier, Wright Marion, and Asa Carmichael.

The following year, editors reported exciting news, noting:

Among the many enterprises and improvements in our County will be the construction of a telephone from Milner’s Corner to Willow Branch for the accommodation of Drs. Troy and Ryon.

Several Civil War veterans and widows lived in Milner’s Corner, such as Jonathon Baldwin, who suffered a gunshot wound in the right thigh. The paper reported in April 1890 that he “received a monthly pension of $4. Joel Manning, gunshot wound in the face, $18 pension. Eliza A. Williamson, widow, pension of $8.”[8]

In January 1903, the paper reported “A bobsled party of fifteen attend Church at Milner’s Corner one night last week.”

According to the Hancock County Democrat, you could get a piece of President Andrew Jackson’s “Ole Hickory Democratic Timber” at Joel Manning’s shop. Milner’s Corner was democratic enclave. Dr. Troy was a candidate for state representative.

Milner’s Corner citizens formed a Citizens Band on April 4, 1913, for a social past time and musical entertainment.[9] Nothing is left at the crossroads except a 1920s cement block building, a house, and barn.

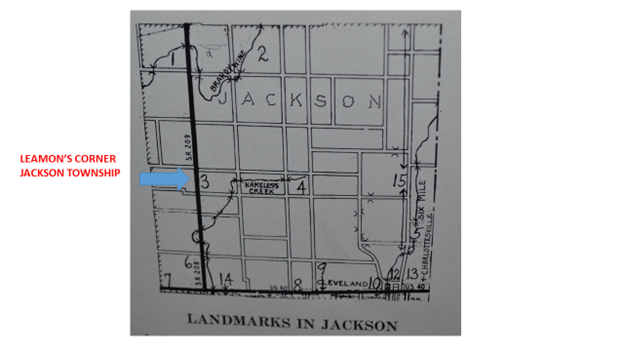

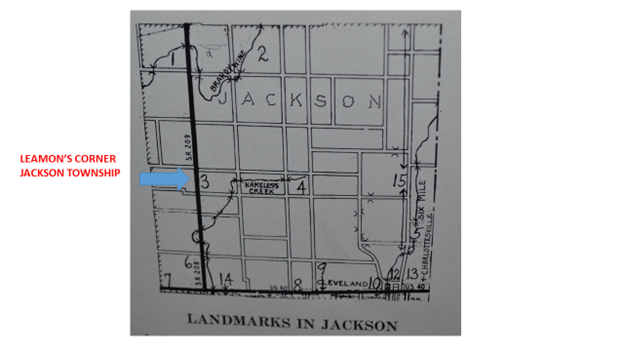

Leamon’s Corner

Leamon’s Corner, named for post office operator Cyrus Leamon, was in Jackson Township. It housed a little store, blacksmith shop, and sawmill. The Missionary Baptist Church was set up in 1878 and Leamon’s Corner Center Friends was erected the following year.[10]

After the post office closed in 1881, George Tague installed a post office in a little grocery he owned the post office, known as Binwood, distributed mail until the late 1880s. The blacksmith shop in Leamon’s Corner was run by Bud Phillips’s son of Thomas Phillips in 1906. Leamon’s Corner Ball Club defeated the Shamrock’s of Greenfield that same year. The Leamon’s Corner Telephone Company was incorporated April 1, 1902, with $140 in capital.

The Hancock County Democrat on July 29, 1879, reported on entertainment provided by Leamon’s Corner’s Literary Society, noting:

The entertainment promises to be the best ever given in the County, consisting of declarations, orations, poems, addresses, comic recitations, songs, plays and &c. Let every lover of education attend. There will be good music and ample refreshments. The county teachers are all invited to attend.

The first public school in Jackson Township was at Leamon’s Corner, known as District 4. Seats were cut from slabs of wood and rubbed as smooth as possible. Wooden legs were bored into the seats. Water came from a nearby stream and all the students drank from the same bucket. Teachers employed corporeal punishment, using a boot jack and some switches. Holes and pins in the wall served as hat and coat rack.

These lost towns of Hancock County like other counties are important to the study of the community and local history. Small towns changed gradually before WW I, some disappeared, and some never got started. Author Thomas Schlereth gives interesting insight and definition into the study of these communities, local history, and possibly lost towns, which he labels “landscape history.” As a matter of explanation, Schlereth defines archaeology as the work of researchers “who usually excavated the material remains of past cultures and through such evidence, attempt to recreate the history of a community from the earliest past.” Schlereth goes to tell us:

Above ground archaeologists, unlike their below ground colleagues, dig into the past but usually on the surface; they examine what they find before it is buried by time and chance. Above ground archaeologists can be called landscape historians. Landscape historians are intent at looking at objects, be they pot chards or service stations with an intense symptomatic and precise scrutiny that ultimately yields specific cultural information from single artifacts as well as braided cultural patterns.

But like tree rings, the evidence of the past comes easily enough to hand but we need to see it, read it and explain it before it can be used to further tell the story of the lost towns of Hancock County.

* Mark Sullivan also contributed to this post. He is a native of Schoharie, New York. He retired as a Command Sergeant Major from the US Army in 2009, having served for 25 years, and currently works as a Department of the Army Civilian at the Finance Center on Fort Harrison, Indianapolis, Indiana. He is a frequent contributor to the Log Chain, the historical magazine of the Hancock County Historical Society.

Sources:

Richman History of Hancock County

Binford History of Hancock County

Glimpses of the Past, Hancock County Historical Society

Interview John Milburn Hancock County GIS Coordinator

Interview Tom Vanduyn Upper White River Archaeological Association

Interview Michael Kester, President of the Hancock County Historical Society

Interview Steve Jackson, Madison County Historian

Interview Steve Barnett, Marion County Historian

Graphics by Mark Sullivan

Notes:

[1] It was located on the northeast corner of the southwest corner of section 33, township 15, range 8.

[2] The store was about a half mile west of the southeast corner of the Blue River Township.

[3] The original survey consisted of 32 lots.

[4] There was never a post office at Nashville.

[5] It was on the east bluffs of the Brandywine.

[6] The red barn on the NW Corner of 900N was built in the 1840’s. Some of the beams in the barn were marked with the date 07-1849 and signed by Henry Milner in red paint. The barn has had a section added to the original structure. Some of the cross beams in the barn are hewed from standing timber. These beams are marked from timber working tools of the period. There are also racks to hang harnesses and collars from the beams. The barn is now protected with sheet metal covering and concrete pillars.

[7] Other storekeepers included John Dawson, Henry Milner, Nimrod Davis, Joseph DeCamp, Caldwell & Keller, William and Joseph Bills, S. A. Troy, Tague & Brother, and W. Vanzant. Merchants included David McKinsey, Nimrod Davis, Charles H. Troy, Charles Albea, Sanford Cable, Frank Pritchard, who also conducted a store. Milner’s Corner had its blacksmith Shops and sawmills. Cyrus Manning and his son conducted a blacksmith shop at the site. Vandyke was another blacksmith. Wood workers include Josiah Long and Joel. Manning. There was a steam sawmill owned by L. Tucker. It had a capacity of five thousand feet per day.

[8] Among the physicians who were located there including D.H. Myers, George Williams, Charles Pratt, and S.A.Troy. Dr. Troy served the community for several years.

[9] Noble H. Troy was the manager; Aubery Thomas, director; Ralph Fisk, C.H. Jackson, Roy Hassler and Glen Johns, cornetists; Robert Troy and James Barnard, baritones; Dale Troy and Luther Barnard, trombones, Lon Godby alto; Chester Alford tenor; Jess Hayes, tuba; Edward Jones and Robert Dorman, drummers.

[10] On June 15, 1905, a meeting was held near Leamon’s Corner. Evangelist John Hatfield and Rev. Williamson presiding. In July 1905 there was a holiness meeting at Leamon’s Corner with the Rev. Worth presiding.