When we look at statues and oil paintings of Civil War leaders today, it’s easy to see them all as career military men trained in strategy and combat tactics with a lifetime of professional experience. But most of those who served in the Civil War were just regular people, not trained soldiers. They were farmers and laborers, trying to make ends meet and provide for their families. And yet when President Lincoln called for volunteers at the outbreak of the conflict in 1861, hundreds of thousands answered, prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice. Why? What would inspire a Hoosier farmer to leave his wife, children, and homestead to fight an ideological war from which he might never return?

While some have argued that the average soldier did not understand the causes of the Civil War, leading scholars, notably including the Pulitzer-Prize winning historian James McPherson, have shown otherwise. With literacy rates and newspaper circulation on the rise, Americans were tapped into current events and politics, including ideological clashes over slavery. They formed debating groups and joined political clubs. They had strong opinions about the democratic experiment and preserving the Union. Indiana residents volunteered in great numbers and encouraged their neighbors and family members to do the same. Many expressed a patriotic duty to serve their country, but some also explicitly fought to end slavery. The battlefield letters of one Hoosier farmer, William A. Swaim of Wells County, provide insight into why one such man served and sacrificed.[1]

William Achsah Swaim was born in New Jersey in 1819. He married Hannah Toy in 1844 and the couple moved to Ohio. There, he worked as a blacksmith and, for a time, manufactured steel plows. In the late 1850s, Swaim moved to a farm just north of Ossian in Wells County, Indiana. From his personal letters it is clear that he was a loving husband and father of five children and that he managed a successful farm, growing corn, rye, wheat, apples, and clover, and raising cows and pigs. He was leading a peaceable, simple, and secure life. But the nation was in turmoil.[2]

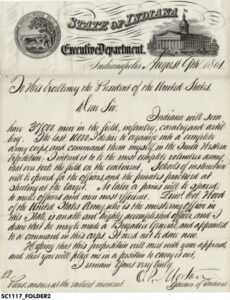

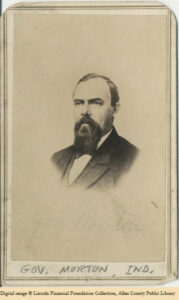

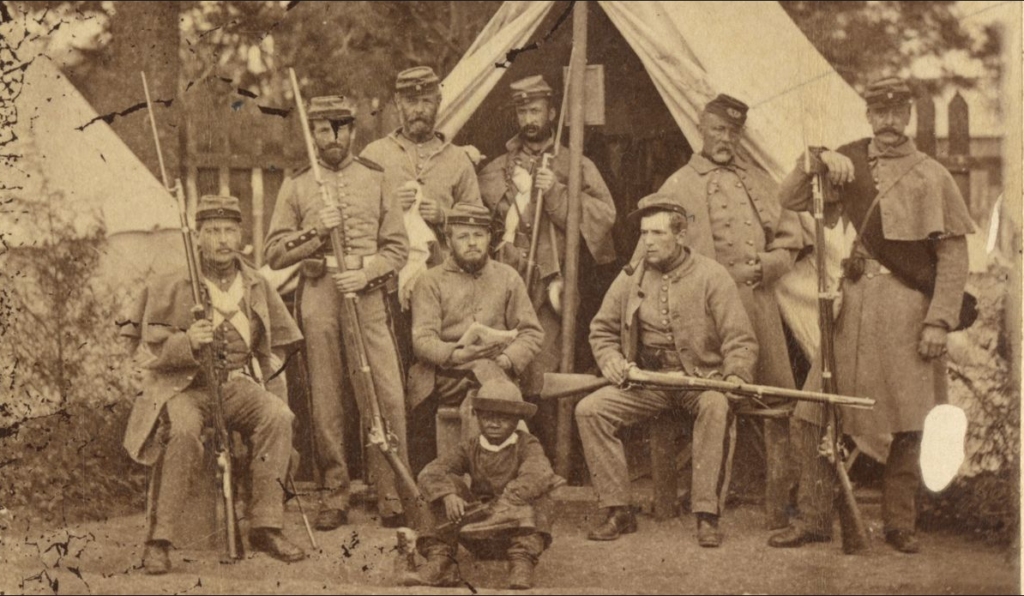

In the summer of 1861, just days after Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton wrote to President Abraham Lincoln promising to send tens of thousands of Indiana troops, William Swaim enlisted in the Union Army. Swaim also helped raise a company of volunteers from Wells County, mainly from the small towns of Ossian, Murray, and Bluffton. His ability to inspire these men to enlist attests to his prominence in the community. Among the men who formed Company A of the 34th Regiment Indiana Volunteers was Swaim’s son James who was only sixteen years old.[3]

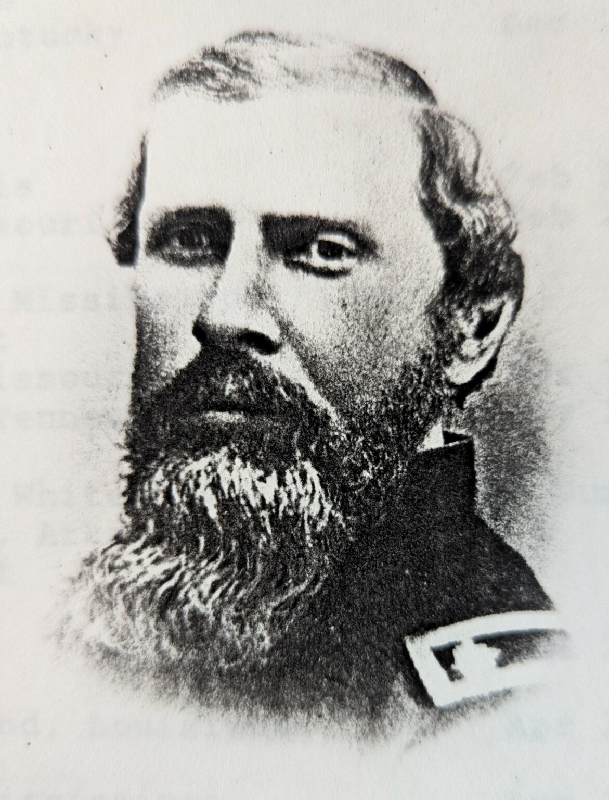

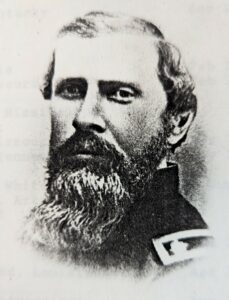

Recognizing his natural capacity for leadership, the men of the 34th Regiment elected William Swaim as their captain. The regiment mustered in Anderson in September 1861. Almost immediately Swaim identified issues with the camp and areas in which the men needed to improve and he stepped into a leadership position – even above his official rank – to make the necessary changes. With a dearth of experienced military leaders in the Army at the time, this is something that he would do throughout his service.

He often wrote about serving in such leadership roles in letters home to his wife Hannah. (Modern readers will have to excuse Swaim’s spelling and try to absorb the crux of his words.) Upon arriving at Anderson, he began ordering soldiers to clean up their clothing and belongings. He wrote, “I yesterday acted as comander of the camp[.] You better believe I feelt some what awkerd but I done the best I could have.” He continued, “One consulation, there is plently as green as I am and worse than myself.” His words demonstrate that Swaim was one of many average citizens who would have to rise to the occasion and become military leaders.[4]

Swaim and the 34th soon travelled to Indianapolis before setting up at Camp Jo Holt in Jeffersonville, just across the Ohio River from Louisville. Here, they waited for rifles and orders. He wrote, “We expect to go to Kentucky soon as we get our guns and in all probility will find something to do and that is what we all want.” It was important to Swaim to prove his bravery and he wanted to see action. He continued:

In [skirmishes] all places of honor are the most dangerous but that is just the place for me[.] If I come out of this war let me come out honorable.[5]

While commendable, this bravery was not uncommon during the war, largely because of the bonds the men built together. Historian James McPherson argued that because regiments were composed of men from the same region, they were motivated to uphold the reputation of themselves, their families, and their hometowns. This was certainly true for Swaim who instructed his wife to tell the folks back home in Ossian that the company was anxious to join the fight and that when they hear about the regiment “you will hear that [we] maintained our honour.”[6]

By November 1861, the weather had turned cold with three inches of snow. The 34th still hadn’t seen any action but remained in good spirits and eager to serve. The Indiana Herald (Huntington) published “The Hoosier Thirty-Fourth,” a poem, or perhaps song, composed by the men. Among the stanzas was this ode to Swaim:

Capt. Swaim will meet them on the field,

And show them that we fear

No Southerner when they fight

The Hoosier Volunteers.[7]

Ostendorf Collection, Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Allen County Public Library, accessed Indiana Memory.

The 34th also expressed their devotion to Governor Morton and became known as the “Morton Rifles.” They even appealed to the Indiana General Assembly, encouraging their legislators to provide Morton with whatever manpower and resources needed for the war effort. They wrote:

Then we ask of you that you work earnestly and unitedly to do what you can to crush this rebellion, furnishing all the means necessary, and looking at no expense, so that it may save our country and give our children an undivided inheritance and a permanent peace. Especially we do ask that you would sustain our present worthy Governor, who, since the commencement of this struggle, has devoted himself entirely to the great work of preserving intact the greatest and best republic that ever existed.

They asked their legislators to earmark money for Governor Morton to call up more troops and create hospitals for sick and wounded soldiers and they asked for a “resolution of thanks” to Morton, whom they called “the soldier’s friend.” Swaim wrote that “the document was Signed by Every officer and nearly every man in the Regt.”[8]

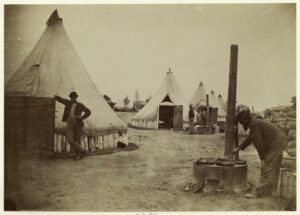

The 34th finally crossed over into New Haven, Kentucky in late November 1861, marching to Camp Wickliffe in December and remaining until February 1862. During this stay, it rained often, camp was muddy, and many men caught colds. Swaim and his son James, whom he referred to as Jim, made the best of it, sharing a Sibley tent, eating well, and writing home. Swaim often answered his other children’s questions about camp life, giving detailed descriptions of their dinner – bean soup, crackers, pickles, and black coffee with sugar.[9]

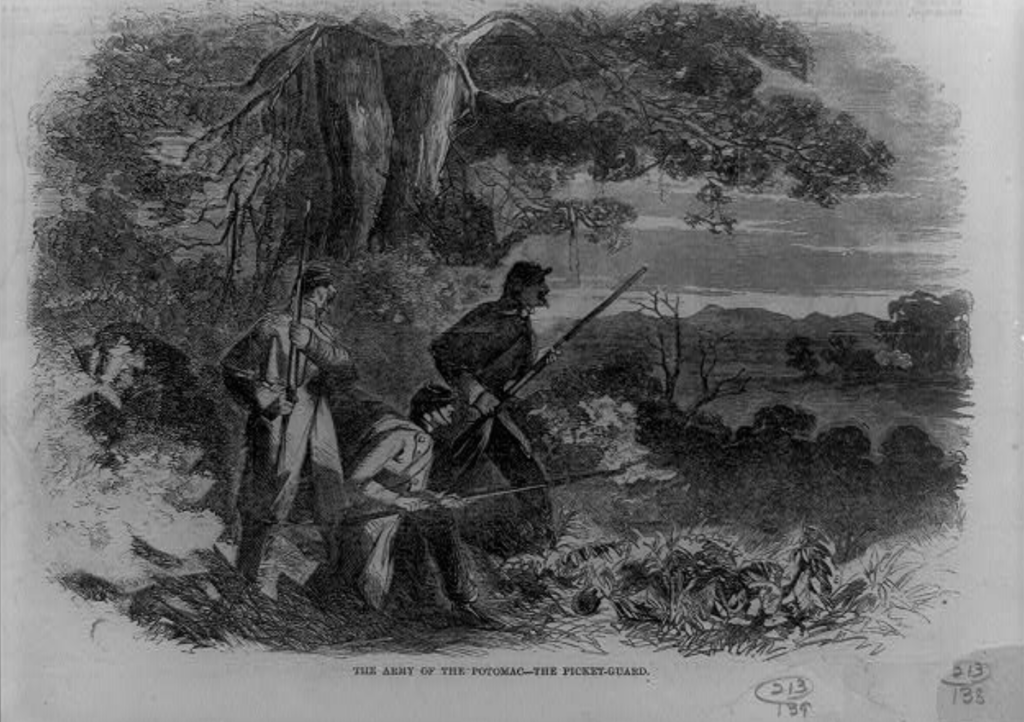

While stationed at Camp Wickliffe, the Wells County men of Company A often performed picket duty, surveilling the enemy lines for any movement. Swaim also rode out to evaluate the men of other companies on picket duty, moving or replacing them as he saw fit. Sometimes this travel allowed him to stay and eat at the home of a local woman. He made sure to write and let Hannah know that he found his host to have a “homely” appearance. Swaim sent Hannah such assurances on several occasions, a sign of his ongoing affection for his wife. He also wrote that he was sure it seemed like the regiment was moving slowly, but that they were indeed preparing for a battle that would be “a grand Sight and one that I have long wished to see.” He explained that he knew “many men will have to be left buryed in the Solders grave but it will be a gloryious death if we conqurer in the end.”[10]

As various leaders of the 34th resigned, moved to other regiments, or fell ill, Swaim again acted in positions above his rank as captain at Camp Wickliffe. On January 19, 1862, he told Hannah that he had been acting as colonel for the past week, drilling the regiments and meeting with the “Brass.” And a week later, he wrote that he was acting as “Captain, Major and Colonel and shall have to till the staff is filled.” He stated that he would not be surprised if Governor Morton approved a higher appointment for him very soon. He was correct. On February 16, Swaim was commissioned the rank of Major.[11]

Meanwhile, Hannah Swaim ran the farm, cared for the children, and arranged business deals – selling corn and grain and making payments on their house. She often wrote to William for his advice, but never asked him to come home. He praised her for this support and told her how much he wished he could see her and “the little ones,” but stood firm in his desire to do his duty to his country.[12]

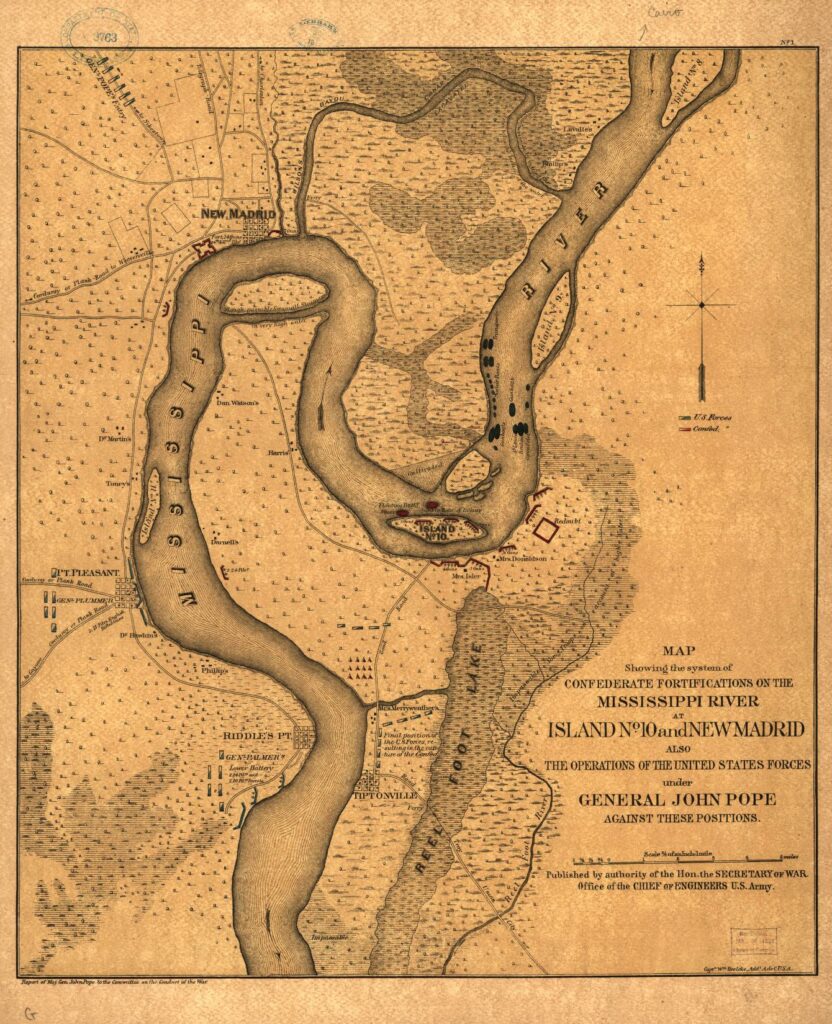

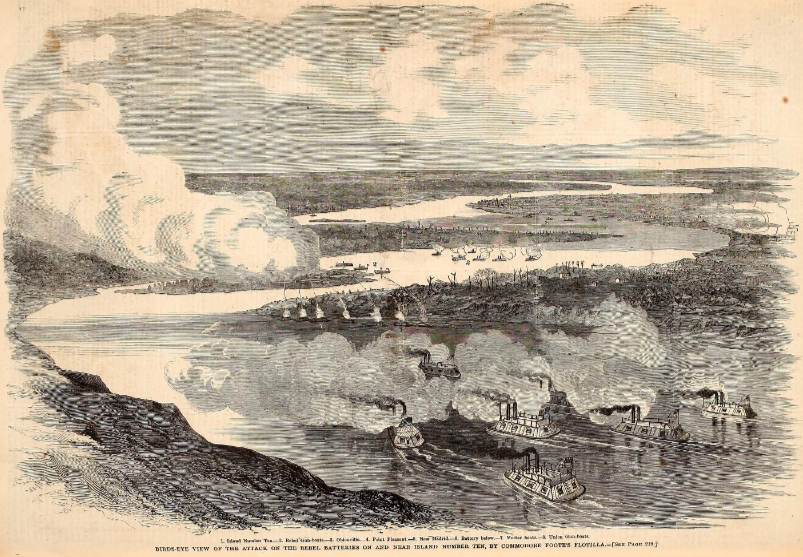

In March 1862, the 34th Regiment finally saw action, joining the Siege of New Madrid (Battle of Island Number 10) on the Mississippi River at the border between Tennessee and Missouri. The 34th joined the siege, but Swaim reported that their field guns were too light compared to the Confederate gun boats firing on them from the river. He wrote to Hannah about shells passing over their heads in their wooded position three-quarters of a mile from the main action, where they were stationed to protect a battery of field guns. He said that as the shells “howeled pass they make a screaming noise” until they “burst in pieces and fly in every direction.” He reported that while some of the boys turned pale, “give them a chance and they will fight to all distruction.” Before signing off, he told Hannah: “If we shall fall in battle it would be a gloryious death and an honorable one.”[13]

Larger artillery soon arrived and Union forces took New Madrid before combined Army and Navy operations led to the capture of Island Number 10. (Learn more about how “Union Army and Navy commanders maneuvered their forces to capture the most formidable Confederate river strongpoint north of Vicksburg” from the U.S. Naval Institute). With the capture of strategic Confederate positions along a bend in the Mississippi River at New Madrid, Missouri and the small nearby island, the Union gained control of the river all the way to Fort Pillow in Tennessee. Swaim had proved his leadership in battle and was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel June 15, 1862.[14]

As the 34th continued South, they saw action at Grand Prairie near Aberdeen, Arkansas before serving on garrison duty in Helena, Arkansas. Swaim described the changing scenery as they marched by abandoned fields of corn and blooming cotton. He and his son James experienced bouts of dysentery, but were able to recover fairly quickly. He complained about inaccurate reports of troop movements in the newspapers. He often wrote about the new draft and hoped that the numbers would fill the places of those in his regiment who had been killed, injured, or fallen ill.

And he seemed puzzled and indifferent to a sick Black man attempting to travel with the regiment. He wrote in dehumanizing language about this ill man, potentially a self-emancipated formerly enslaved person looking for protection.[15] But while he likely held prejudices against Black southerners, or Black people more generally, Swaim was also vehemently opposed to slavery. He believed not simply that it should not be extended into new territories, like many anti-slavery advocates at the time, but that it should be abolished. And he was ready to give life for this ideological belief.

In August 1862, he wrote to Hannah about a letter he received from Han Platt, a relative of the Swaims. Platt had written of news from home but also that she was encouraging her family not to enlist. She called it “a Negro war” and said “the Abalitionest and Negros ought to fight it out.” Swaim was livid. He told his wife:

I answered her by saying that I had been an Abalitionist for nearly thirty years and Gloryed in it . . . I told her that I had one Son with me in the Armey with me and if he either died by Sickness or by bullets from the Enemey it would be a great consolation to me to know that I had one relation who had curage enough to face Danger with me in Defence of our Countrey.[16]

In a September 1862 letter home, he praised the “splendid” cooking of two Black women, a mother and daughter, who had self-emancipated from enslavement as “house servants” and were travelling with the camp as cooks. He wrote of their desire to return North with the regiment and that the colonel was going to employ them in his home after the war. Before closing, Swaim expressed his “contempt for such men as bye [buy] and sell and abuse” Black women. It is possible that as he got to know more Black people, his empathy and understanding increased. When he wrote to Hannah again in December (after she had come in person for a visit) and reported on everyone’s health, he made sure to include: “We are all well in our Mess including the 3 Negro[s].”[17] [Learn more about Black freedom seekers in Union camps through the National Archives.]

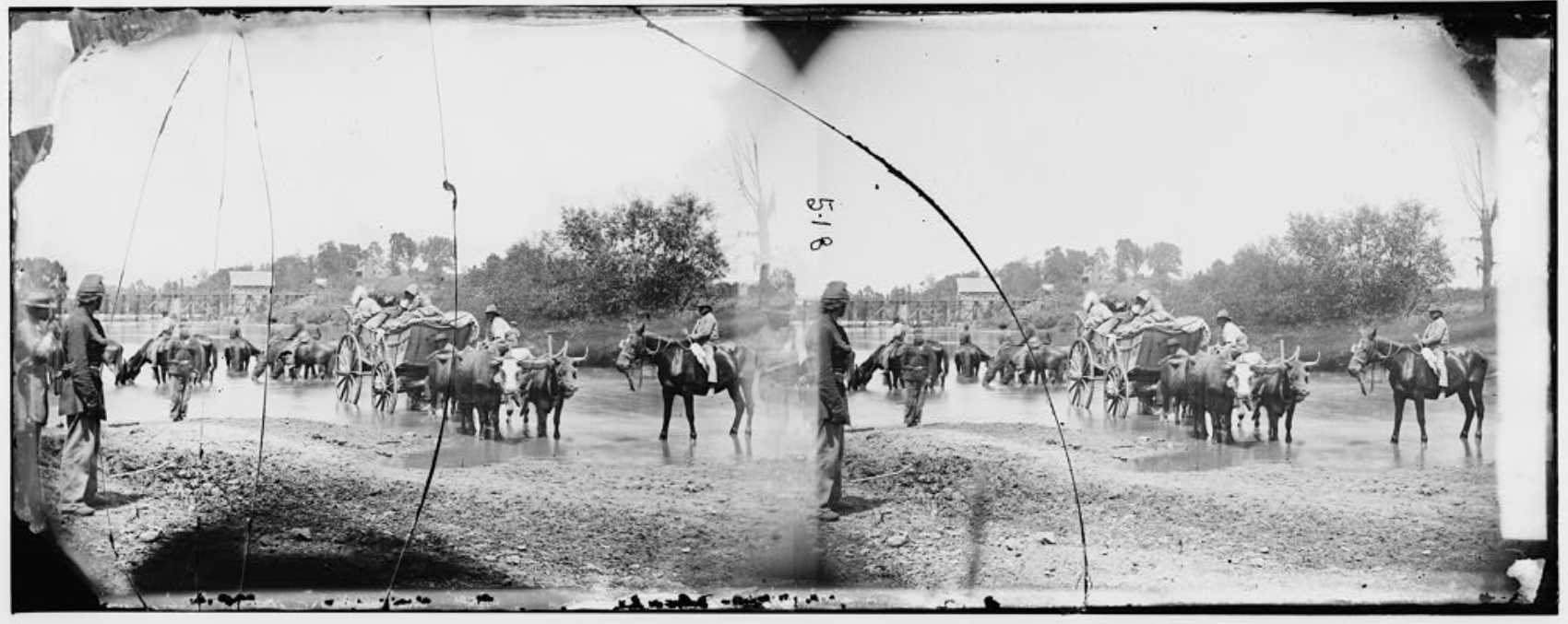

When the 34th left Helena in January 1863, Swaim told Hannah that a “Black boy Gorge” (likely George) continued to travel with them. But a Black man named “Corneleous” (likely Cornelius) had to stay behind because he had a wife and General Sherman was not allowing and women or citizens south of Helena as he prepared for a major offensive at Vicksburg. Swaim paid Cornelius thirty dollars in some sort of business transaction and “told him to take his money and with it find a place of Freedom . . . he said that was his intentions.”[18]

In another letter, Swaim expressed concern over leaving so many freedom seekers behind, worried about what would happen to them, and hoping that the war would end their plight. He wrote in a February letter:

We think at this time we have a fair prospect of victory ahead . . . over that monster Slavery, which has cost us So meny lives and so much truble[.] Every Senciable man and well wisher of his countrey now admits that it must be distroyed to insure us a lasting piece.[19]

In April 1863, the 34th joined the Vicksburg Campaign as part of Brig. Gen Alvin Hovey’s Division. (A native of Mount Vernon, Indiana, Hovey would go on to serve as the 21st Governor of Indiana). Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign would cut supply lines and destroy manufacturing centers before marching on the Confederate stronghold at Vicksburg. As the 34th headed towards Vicksburg, the greatest danger they had yet faced, Swaim told Hannah:

I feel that we are in the most Righteous war that ever any body was in and if we fall we fall in a good cause — if we get into fight I expect to do my Duty as an officer and leave no stain upon my Character or disgrace upon you or my children[.] I wish you to act the part of a Soldiers wife take things as they come and be redy for the Worst.[20]

Indeed the worst was yet to come.

On April 30, 1863, the 34th Regiment crossed the Mississippi at Bruinsburg and then “marched all night and engaged the enemy at daylight” during the Battle of Port Gibson. The regiment made “a charge during the battle . . . capturing two field pieces and forty-nine prisoners.” They suffered heavy losses.[21]

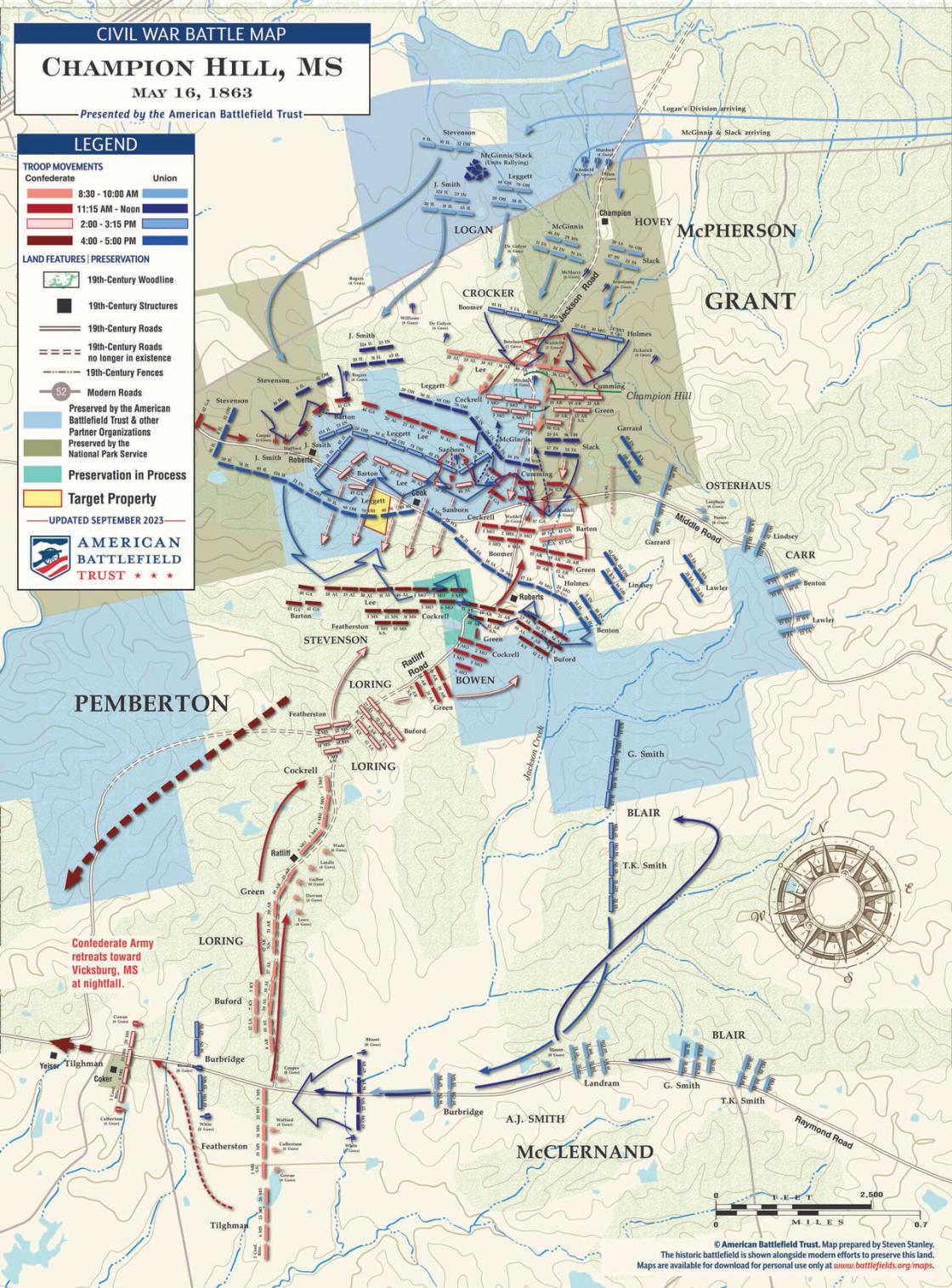

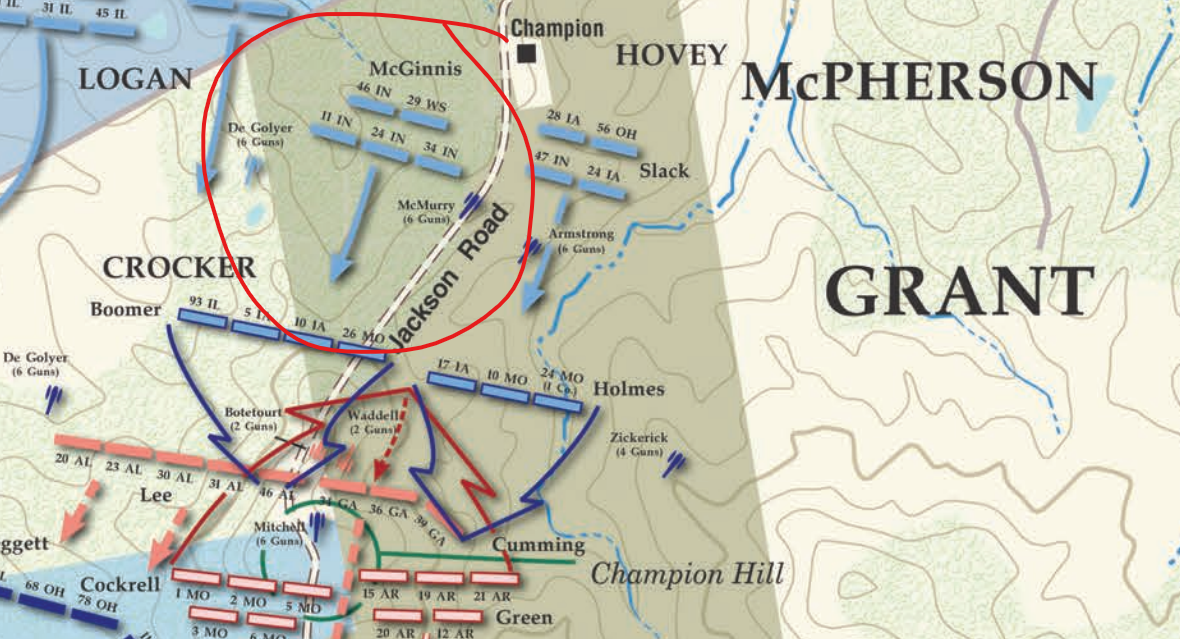

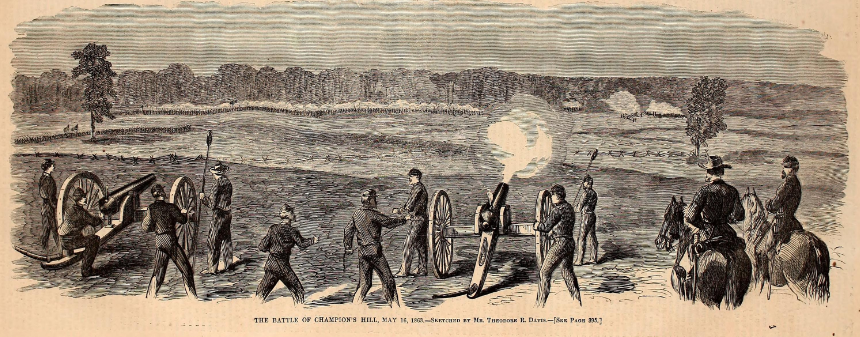

Major General Grant moved his forces towards Vicksburg, which Jefferson Davis described as the “nailhead” holding the Confederacy together. Taking Vicksburg would give the Union control of the Mississippi and split the Confederacy in half, isolating both sides from reinforcements and supplies. On May 16, 1863, Swaim and the 34th were among Maj. Gen. Grant’s Union forces who engaged Gen. John Pemberton’s Confederate forces in the Battle of Champion Hill, the bloodiest and most significant conflict of the Vicksburg Campaign.[22]

According to the American Battlefield Trust, Maj. Gen. Grant ordered and attack on Pemberton’s defensive line at around 10:00 a.m. This attack was led by divisions under Maj. Gen John A. Logan and Brig. Gen. Hovey, which included the 34th. By 11:30, these two Union brigades reached the main Confederate defensive line and by 1:00 had pushed the Confederates back from the hill and captured the main roads.[23]

In a furious counterattack, the Confederates pushed Union forces back and nearly retook control of Champion Hill, but were outnumbered. Pemberton’s troops were forced to retreat towards Vicksburg. After a 47-day siege, Union troops would also take Vicksburg, turning the tide of the war in their favor.[24]

Lieut. Col. Swain [sic], 34th Indiana, was severely wounded whilst cherring his men and encouraging them in the performance of their duty.[25]

As the rest of the 34th marched on to Vicksburg, Swaim was moved to a nearby hospital, accompanied by his son Jim who helped care for him. While many newspapers reported that Swaim had died on the battlefield, he actually seemed to improve for several weeks. Jim wrote to Hannah:

I received a letter from you today when on the 31 of May you said that you had seen in the papers that pop had been killed at Champion Hills[.] It is all a mistake[.] [26]

Jim reported that while William was severely wounded, he had left the morning of June 12 with a doctor first to Memphis to secure a medical leave of absence and then move to Ossian. Jim concluded, “I expect that he will get home before this letter does.”[27]

But Swaim never made it home. On June 16 or 17, 1863, on his long journey home, Lt. Col. William Swaim died from the wound he sustained at Champion Hill.[28] It is hard to fathom what it must have been like for Hannah having to lose him twice—first, in the conflicting newspaper reports, and then, the tragic arrival of the fallen citizen soldier. But she would have to be strong for her other children. Jim survived the war, continuing on with the 34th Indiana Regiment, which fought in the very last conflict of the Civil War at the Battle of Palmito Ranch, Texas.[29]

Swaim was buried in the Ossian Cemetery (and later moved to nearby Oak Lawn cemetery). The 34th Regiment wrote to Hannah in July signing a unanimous resolution stating:

That in his death the regiment has siffered [sic] the irreparable loss of a brave, efficient, and faithful officer; the country a high minded unwavering patriot [to] the cause of liberty – a mighty, uncompromising champion, and to society – a jewel of sterling worth whose unswerving integrity – and dauntless courage stood out boldly as an example of imutation [sic].”[30]

Lt. Col. William Swaim was willing to risk his life for his country, for the honor of his family and his hometown, and for the preservation of the Union. But those who claim that Indiana soldiers did not understand and/or care about the underlying cause of the war—ending slavery—do a disservice to the sacrifices of men like Swaim. In his own words to his beloved wife, he expressed his dedication to abolishing “that monster Slavery” and was prepared to die for that cause. In the end, Swaim did just that. He gave his life in “the most Righteous war” to make the United States a more perfect union, one without the abomination of slavery.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to Larry Heckber for introducing me to Swaim’s story through his ongoing commitment to the history of Wells County and the preservation of the Ossian Cemetery. And thank you to UIndy student and IHB intern Sam Elder for his help in researching this project.

Notes:

[1] James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988); Thomas E. Rodgers, “Hoosier Soldiers in the Civil War,” Civil War 150th, Indiana Historical Bureau, accessed in.gov/history.

[2] William Swaim and Hannah Taeg (Toy), Mariage Record, December 28, 1844, Burlington New Jersey, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; 1850 U.S. Federal Census, Troy, Miami County, Ohio, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; 1860 U.S. Federal Census, Jefferson Township, Wells County, Indiana, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Tyndall and Lesh, Standard History of Adams and Wells Counties Indiana, vol. 1 (Lewis Pub Co., 1918): 366-67, accessed Archive.org.

[3] Oliver P. Morton to Abraham Lincoln, August 9, 1861, Oliver Morton Papers, Indiana Historical Society; Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana, vol. 2 (Indianapolis: W. R. Holloway, State Printers, 1865), p. 333-343, accessed Internet Archive.

[4] William A. Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, September 15, 1861 in The Civil War Letters of Lieutenant Colonel William Swaim, transcribed by Kent D. Koons (March 1993), Indiana Collections, Indiana State Library; Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana, vol. 2, p. 333-343.

[5] William A. Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, October 16, 1861.

[6] William A. Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, October 22, 1861.

[7] William A. Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, November 4, 1861; “The Hoosier Thirty-Fourth,” Indiana Herald (Huntington), November 27, 1861, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[8] “The Hoosier Thirty-Fourth,” Indiana Herald (Huntington), November 27, 1861, 1; “The Morton Rifles Rallying Song,” Indiana Herald, January 28, 1863, 4; “John Thompson Letter,” Steuben Republican, April 11, 1863, 2; “The Morton Rifles,” New-Orleans Times, June 5, 1864, 4; Document 148: Memorial of the Thirty-Fourth Indiana Volunteers – “Morton Rifles,” in William H. H. Terrell, Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana, vol. 1 (Indianapolis: W. R. Holloway, State Printer, 1869), p. 354-355; Swaim to Toy Swaim, February 6, 1863.

[9] William A. Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, January 9-12, 1862.

[10] Ibid.

[11] William A. Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, January 19, 1862; William A. Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, January 27, 1862.

[12] William A. Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, passim.

[13] William A. Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, March 8, 1862.

[14] Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana, vol. 2, p. 333-343; Lieutenant Commander J. J. Murawski, “Checkmate at New Madrid Bend,” Naval History, April 2018, accessed U.S. Naval Institute.

[15] William Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, August 7, 1862 and August 13, 1862.

[16] William Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, August 13, 1862.

[17] William Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, September 14, 1862.

[18] William Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, January 11, 1863.

[19] William Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, February 6, 1863.

[20] William Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, April 15, 1863.

[21] Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana, vol. 2, p. 342-343.

[22] “Vicksburg,” American Battlefield Trust, accessed https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/vicksburg.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Evansville Daily Journal, June 18, 1863, 4, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[26] James “Jim” Swaim to Hannah Toy Swaim, June 12, 1863 in The Civil War Letters of Private James Swaim, transcribed by Kent D. Koons (March 1993), Indiana Collection, Indiana State Library.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana, vol. 2, p. 333. Sources conflict on the exact date of Swaim’s death. Military records claim June 17 while his headstone reads June 16.

[29] Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana, vol. 2, p. 342-343.

[30] Resolution of the 34th Regiment Indiana, June 30, 1863 enclosed in Col. R. A. Cameron to Hannah Toy Swaim, July 2, 1863.