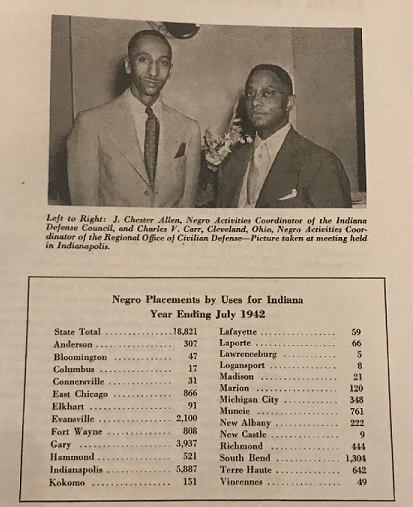

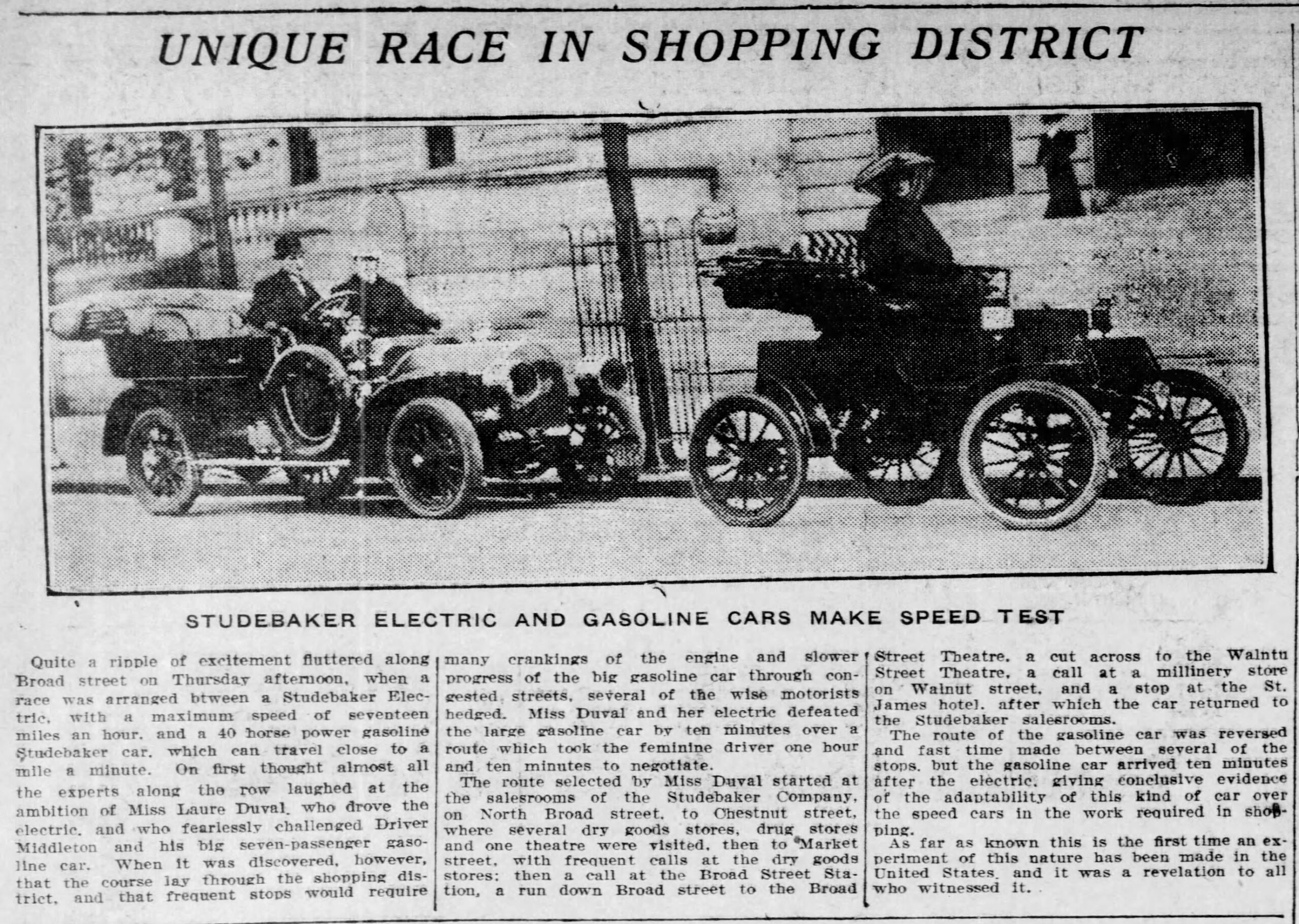

On a “fair, warmer” fall day in Philadelphia, a friendly competition on the city streets occurred. The test would determine whether a “40 horse power gasoline” car or a “runabout” electric car would perform better in the congested thoroughfares of the City of Brotherly Love. Behind the wheel of the gas-powered car sat “Tod” Middleton, described by newspapers as an “expert” driver, “thoroughly familiar with Philadelphia streets.” The electric vehicle’s driver was an “enthusiastic” booster of electric cars, who wanted to prove that they could take on tasks typically associated with gas-powered automobiles.

The rules of the competition were simple: each driver had to make twenty-five trips within Philadelphia’s shopping district, parking and shutting off their car each time they reached a destination. They would then restart their vehicle and travel to the next place on their itinerary. Some of the stops included “department stores, theaters, railroad stations” as well as “hair-dressers, and candy stores.” Whoever completed all their trips the fastest was the winner.

Both drivers started on North Broad Street, making all of the necessary stops within the city’s shopping district, and ending right back where they started. In a shocking twist, the electric car finished first, beating the gas car by ten whole minutes, providing what the Philadelphia Inquirer called “conclusive evidence of the adaptability of this kind of car over the speed cars in the work required in shopping.”

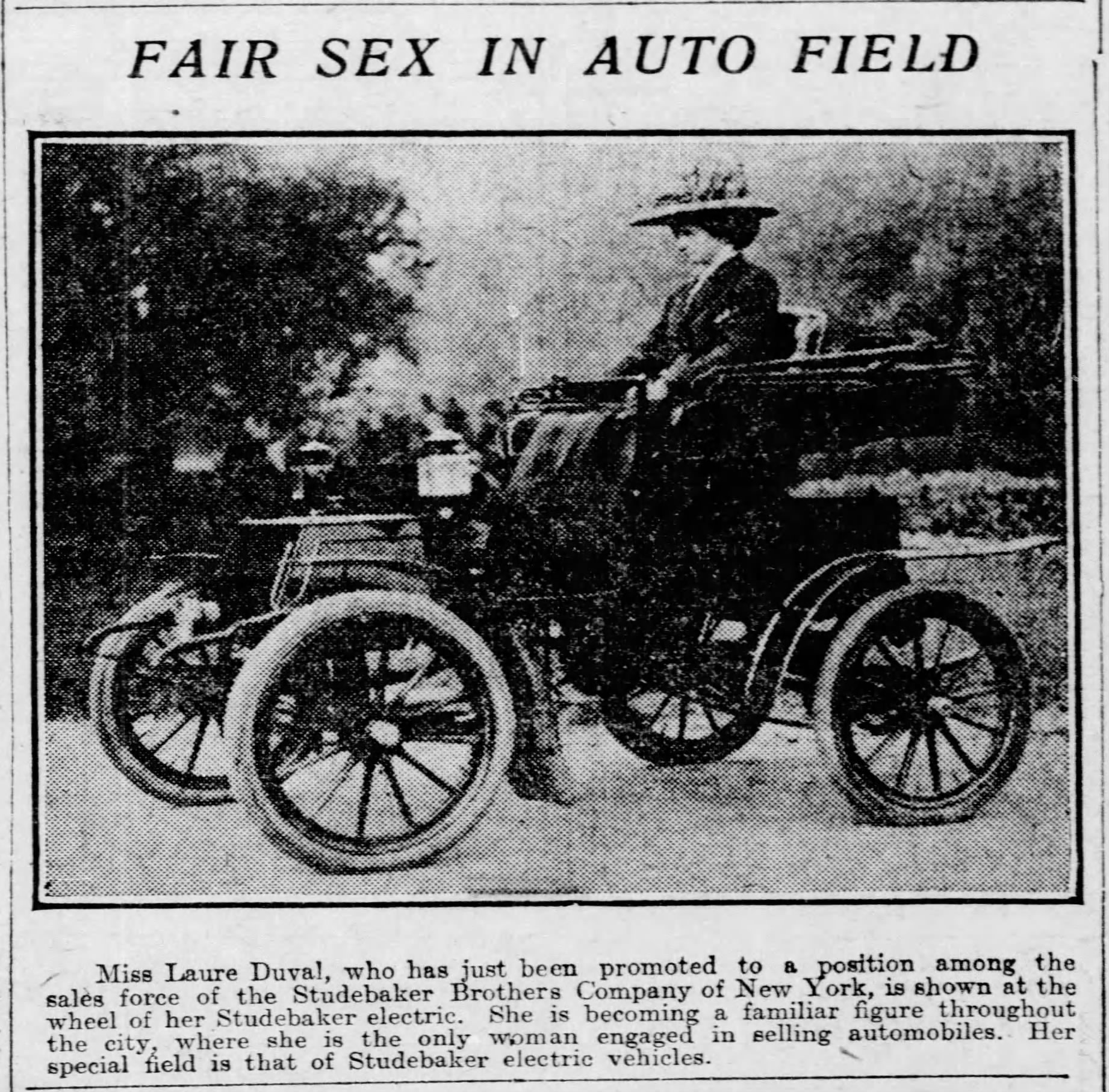

Curiously, this race didn’t happen last week or even last year, and the electric car wasn’t a Tesla or Rivian. It was a Studebaker, the South Bend-based company, and the year was 1908. And the driver of the electric car? Her name was Laure Duval, and she worked as a salesperson at the Studebaker Brothers Company of New York. She wanted to prove the durability, reliability, and efficiency of Studebaker’s electric vehicles. (Efficiency was especially important; since the gasoline car needed to be hand-cranked every time it was started, and the electric car didn’t, this key design component proved instrumental in the 10-minute lead the electric car achieved.) Her race with Tod Middleton received coverage by newspapers all over the country, from Kansas City to San Francisco.

Studebaker’s electric cars became a mainstay of the company during the early years of the 20th century, providing vehicles for personal use as well as transport. They were also marketed in a unique way. Studebaker focused on city businessmen, and especially society women, as the premier customers for electric cars, hence the 1908 Philadelphia car competition. While gas-powered cars became the company’s focus by 1912, Studebaker’s innovative designs and skillful presentation nevertheless made their electric cars more than a mere fad. They showed the country that electric cars could be made cost-effectively and provide customers with a reliable, affordable means of personal transportation.

*

By the time of Studebaker’s foray into electric cars, the company had already been a longstanding success. Founded as a blacksmith shop in the early 1850s by Henry and Clem Studebaker, the company originally specialized in the manufacture of horse-driven vehicles, both for personal transportation and for agriculture. Its fulfillment of military vehicle orders for the Union during the Civil War cemented its reputation, and in 1868, the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company was founded. The firm built a massive manufacturing plant in South Bend and employed well over a thousand people by the 1890s.

By 1897, Studebaker was “building and experimenting with a ‘horseless vehicle’,” according to company minutes. The Centralia Enterprise and Tribune published an article in their July 10, 1897 issue on a meeting of “forty-five Studebaker service men of the New York Metropolitan area . . . for a clinical demonstration and discussion on modern techniques in automobile repairs.” Studebaker employees, from district managers to branch service representatives, actively discussed how the company would build a car for commercial sale.

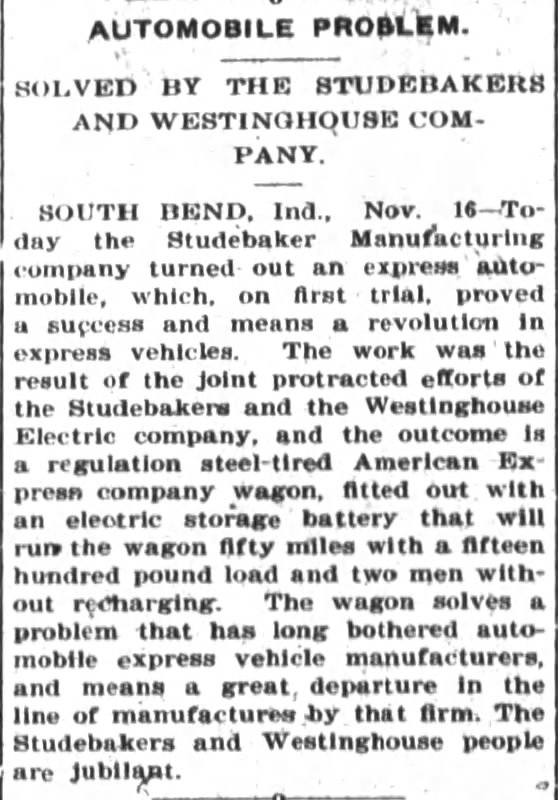

The company got closer to their vision by 1901, with help from two of America’s most visionary inventors. The South Bend Tribune reported that none other than Thomas A. Edison, the man behind the lightbulb and the motion picture camera, designed the battery for one of Studebaker’s two prototype automobile designs. “Mr. Edison has promised the Studebakers that they will have one of the first batteries for vehicle purposes,” the Tribune elaborated. The other vehicle prototype was developed with the assistance of Hiram P. Maxim of Westinghouse, Edison’s bitter corporate rival (and Nikola Tesla’s financial backer) in the legendary “electric current wars” of the 1890s. In the end, Westinghouse came out the victor in the “mini” electric current war, producing a battery that would “run the [electric] wagon fifty miles with a fifteen hundred pound load and two men without charging,” according to the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette in the fall of 1901.

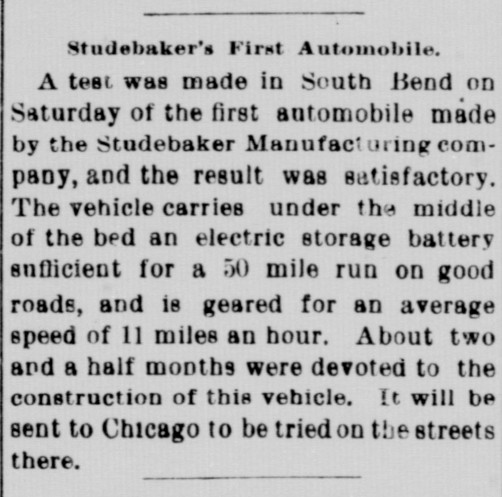

On November 16, 1901, Studebaker successfully tested its first electric automobile. The Marshall County Independent provided more detail on its specifications: “The vehicle carries under the middle of the bed an electric storage battery sufficient for a 50 mile run on good roads, and is geared for an average speed of 11 miles an hour.” The article also noted that Studebaker intended to test their electric car in the streets of Chicago, seven years before Laure Duval’s legendary test in Philadelphia.

Studebaker’s electric cars and trucks were quickly put into production and the company sold twenty by 1902. Studebaker executive Albert Russell Erskine, in his company history, wrote that “the first electric runabout was sold [on] February 12, 1902, to F. W. Blees of Macon, [Missouri].” Now part of this is true. F. W. Blees did, in fact, purchase a Studebaker electric runabout, but the date for his purchase is likely closer to October of 1902, according to a newspaper account in the Macon Times-Democrat. Colonel Blees, a onetime prospective candidate for Georgia Governor, ran a successful carriage business. He purchased the electric runabout while attending the Texas State Fair in Dallas, and according to the Houston Post, the state fair ran from September 27 to October 12, 1902. Blee’s purchase had to occur in this window of time and not in February, as Erskine recounted. Colonel Blees likely used his Studebaker electric car for at least ten years, driving it to “Studebaker Day” at the Georgia State Fair in 1912, as noted by the San Francisco Examiner.

With a Westinghouse motor, an Exide battery, and a body built by Studebaker, described by one advertisement as a “combination that speaks for itself,” the company’s electric runabouts sold for $975 in 1903 ($34,604.97 in 2024 dollars). While the price tag limited the car’s marketability to mostly middle- and upper-class Americans, Studebaker managed to sell them effectively. The company showed off its electric vehicle as a part of its 3,000 square foot exhibit at the 1904 St. Louis Fair, which the South Bend Tribune described as “one of the finest to be seen at the exposition. It is simple in construction, safe, easy to operate, and free from vibration and noise.” This exhibit proved successful, since the Washington Post reported in 1905 that, “the well-known Studebaker electric. . . is meeting with a steady sale, and there will be considerable number of them in evidence on the streets in Washington this season.”

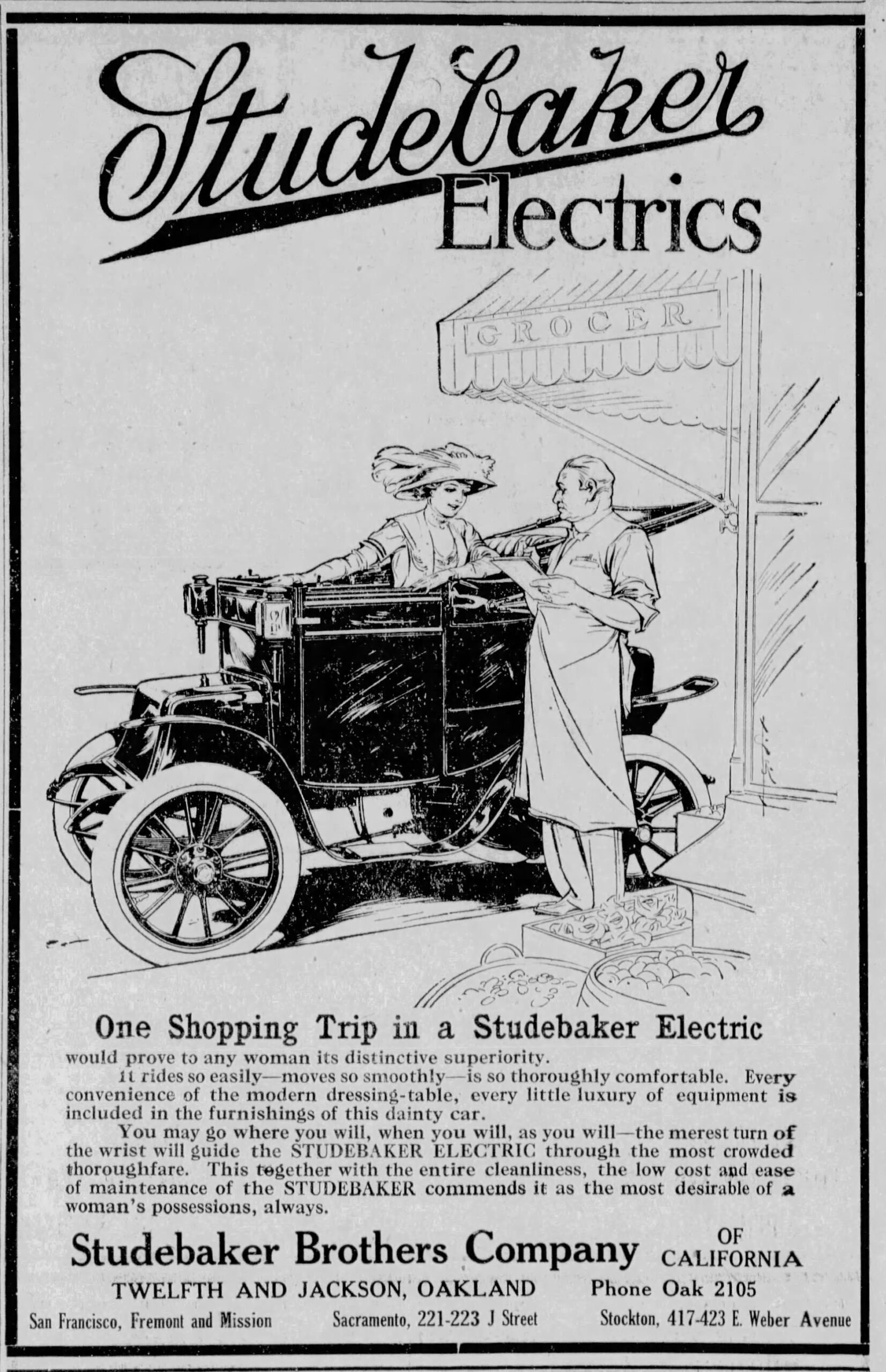

Studebaker’s marketing went beyond public exhibits; it also developed flashy newspaper advertisements to attract customers from two urban demographics: city businessmen and society women. As a 1908 ad in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle attested, “For the woman shopping, or for the business man [sic] to make hurried trips about town, it is the ideal and only vehicle.” As one prime example, John Mohler Studebaker, one of the original Studebaker brothers, can be seen in photographs driving the electric car. The Los Angeles Herald even printed a story about him escorting Wu Ting Fang, a government minister from China, in a Studebaker electric during the foreign leader’s trip to the United States. “Although the trip was a dizzy one,” the Herald wrote, “President Studebaker’s perfect control of the car seemed to inspire Minister Wu with confidence and enjoyed the very unusual trip.”

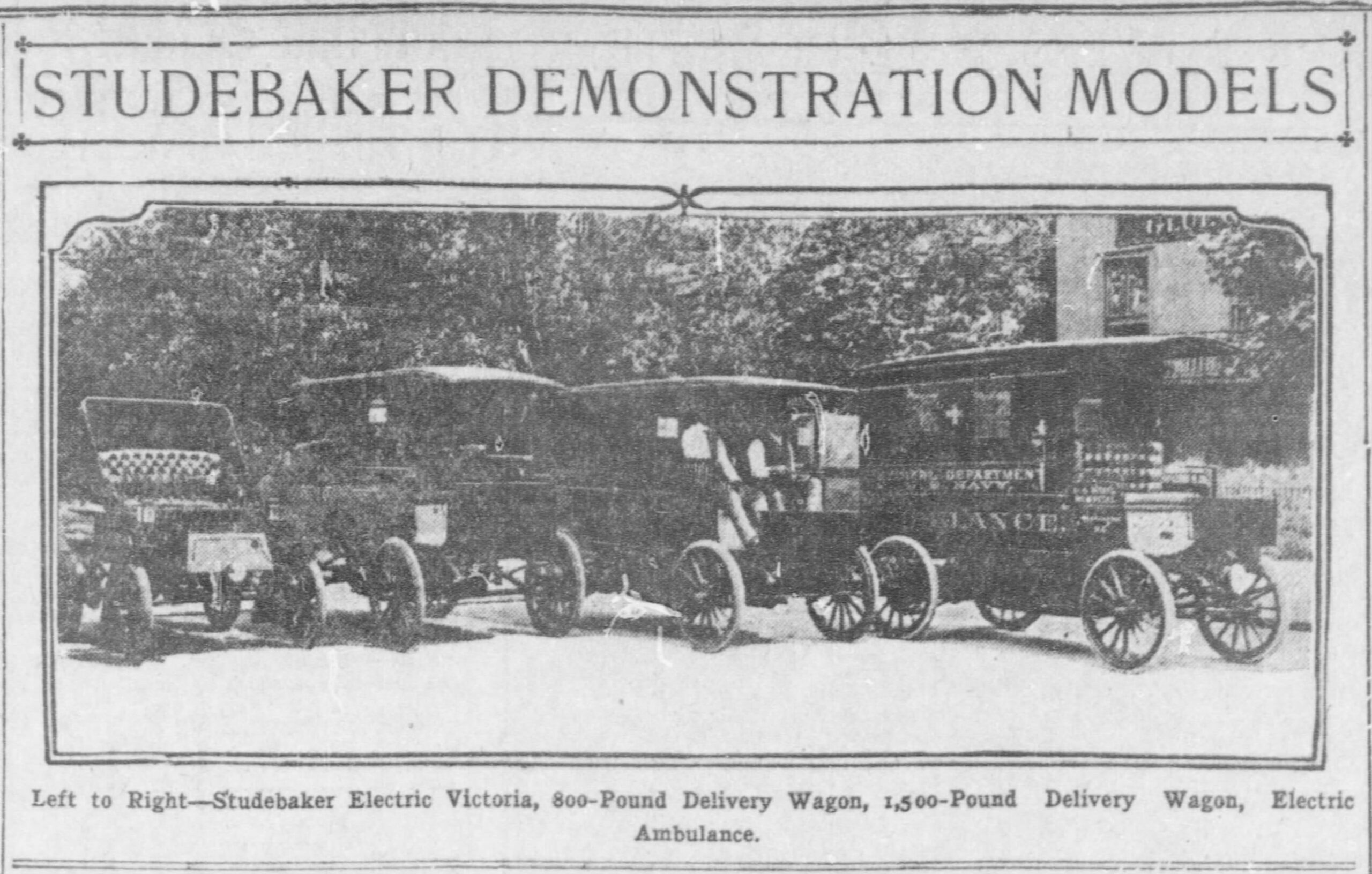

Urban professionals especially took to the Studebaker electric, enticed by ads displaying the ‘gentleman about town’ completing his social calls and articles attesting to its popularity with such men, as Chicago’s Inter Ocean reported. Dr. Jacob Frank, a physician who lived at 49 Pine Grove Avenue, “purchased a new Studebaker electric Victoria last week and uses it daily in calling on his patients,” the Inter Ocean wrote in 1908. Dr. Frank also provided a testimonial to the paper, saying, “I drove a gasoline car for the last two years . . . but for men of my profession it does not compare with the electric for city work. My new Victoria is no trouble whatever and I would not exchange it under any conditions for a gasoline car for around town work.” As a physician who made house calls, the easier starting process for the electric likely shortened time to get to patients and made trips from house to house a smoother experience, as it did for Laure Duval in her legendary race on the streets of Philadelphia.

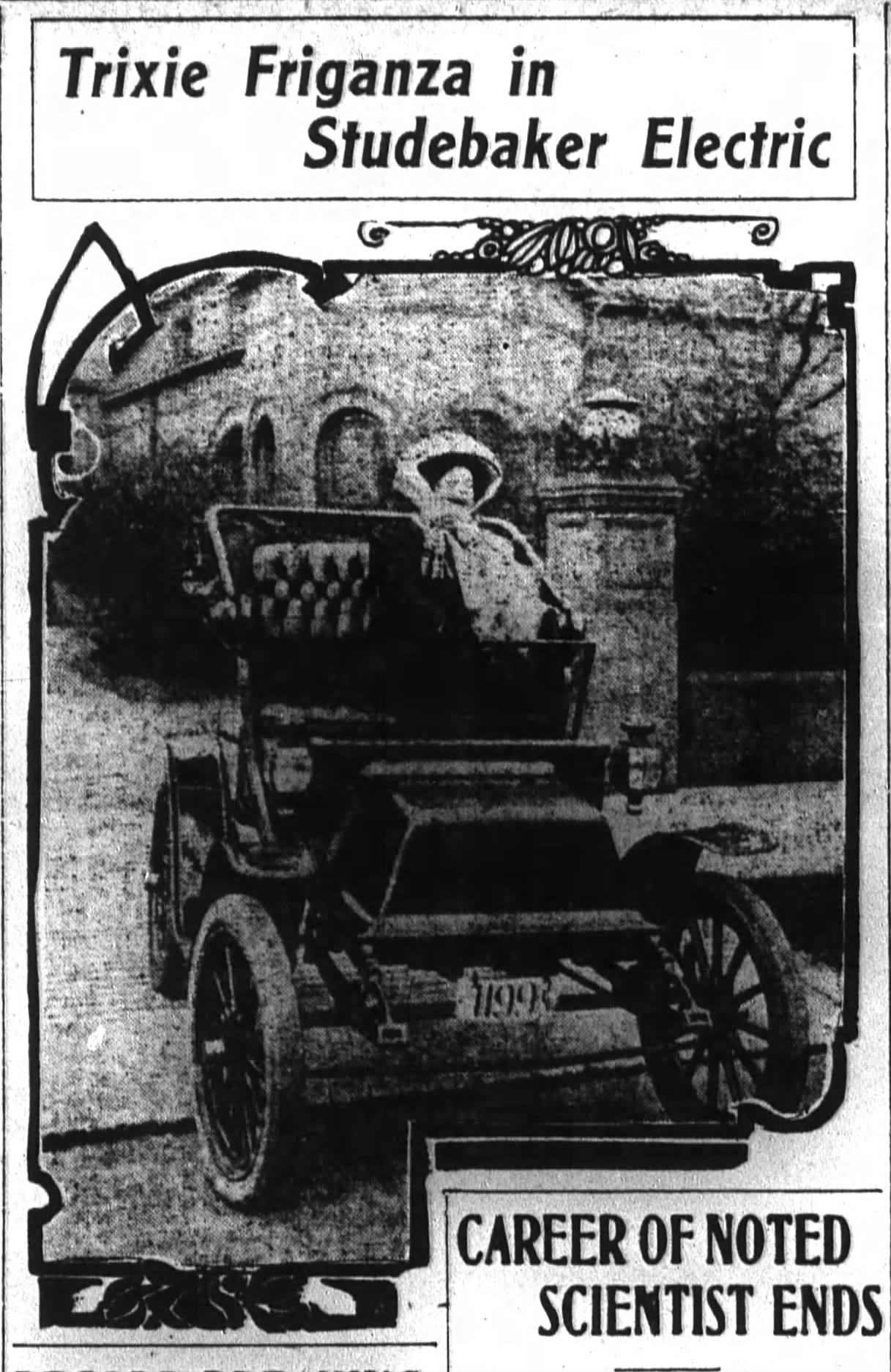

By 1907, the marketing to women, especially society women, become supercharged. The company ran ads proclaiming that “the woman whose social duties require the constant use of a carriage will appreciate that advantage of a Studebaker Electric.” That same year, a photograph in the San Francisco Chronicle showcased a Studebaker electric with none other than actress Trixie Friganza in the driver’s seat. A mainstay of stage and screen for decades, Friganza was also a suffragist and attended rallies in support of women’s rights. That Friganza was willing to be photographed driving a Studebaker electric car spoke to its popularity among successful women, something the company continually leaned into.

According to the city’s Press newspaper in 1910, “a notable number of ladies of Pittsburg’s elite have visited this [Studebaker] exhibition and their expressions of approval and delight are particularly gratifying to the company’s executives.” The Press elaborated on this theme with a society woman’s remarks. “There is an elegance of appearance in the Studebaker electric that easily distinguishes it from all other electric pleasure cars,” she said. Idahoan society women agreed. As the Boise-based Statesman noted, “Mrs. Scott Anderson set the pace with her new Studebaker electric and Mrs. O. P. Johnson has ordered a fine Studebaker electric coupe costing $2500. Mrs. Hall followed suit by ordering a Studebaker electric phaeton.” Additionally, owners could charge their cars at home and travel distances well over fifty miles away. All across the country, from Studebaker’s homebase in Indiana to the sunny coasts of California, the Studebaker electric’s brand became synonymous with simplicity, elegance, and cleanliness.

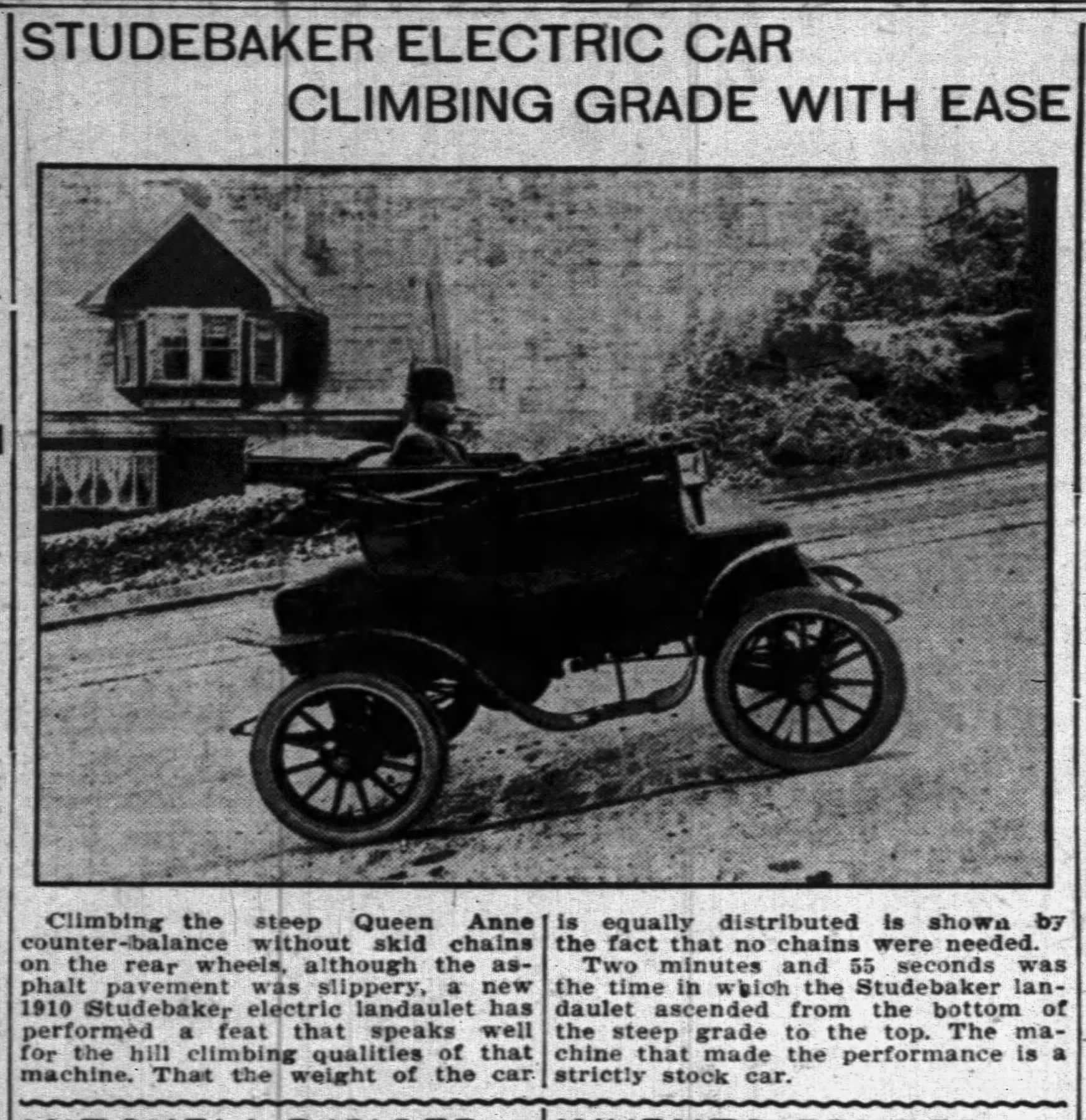

The brand cultivated a reputation for reliability and performance. Numerous newspaper articles documented many interesting experiments with Studebaker electric vehicles. For instance, traveling on rural routes was a concern with potential customers, as Studebaker often marketed its electric vehicles as city transportation. David Clem, a mail carrier in South Bend, tested a Studebaker electric on his rural mail route, with it performing quite well. As the South Bend Tribune reported on July 20, 1907, “the time generally consumed in making the round by Mr. Clem is eight hours, but the auto left the local office at seven in the morning and after completing the trip and delivering the mail, reached the office again at 10 o’clock, consuming only three hours.” Cutting five hours off a rural mail route was pretty impressive, which Mr. Clem likely appreciated. A series of tests in 1908 displayed a Model 22 Studebaker electric runabout expertly traveling from Kansas City, Missouri to Ottawa, Kansas, “in spite of the fact that the roads were very rough in places and a number of steep hills proved to be a severe test for some of the contestants,” the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote. Drivers also received a helping hand from local farmers, “who turned out in force with scrapers and spades and did their best to get the roads in good condition for the tests.”

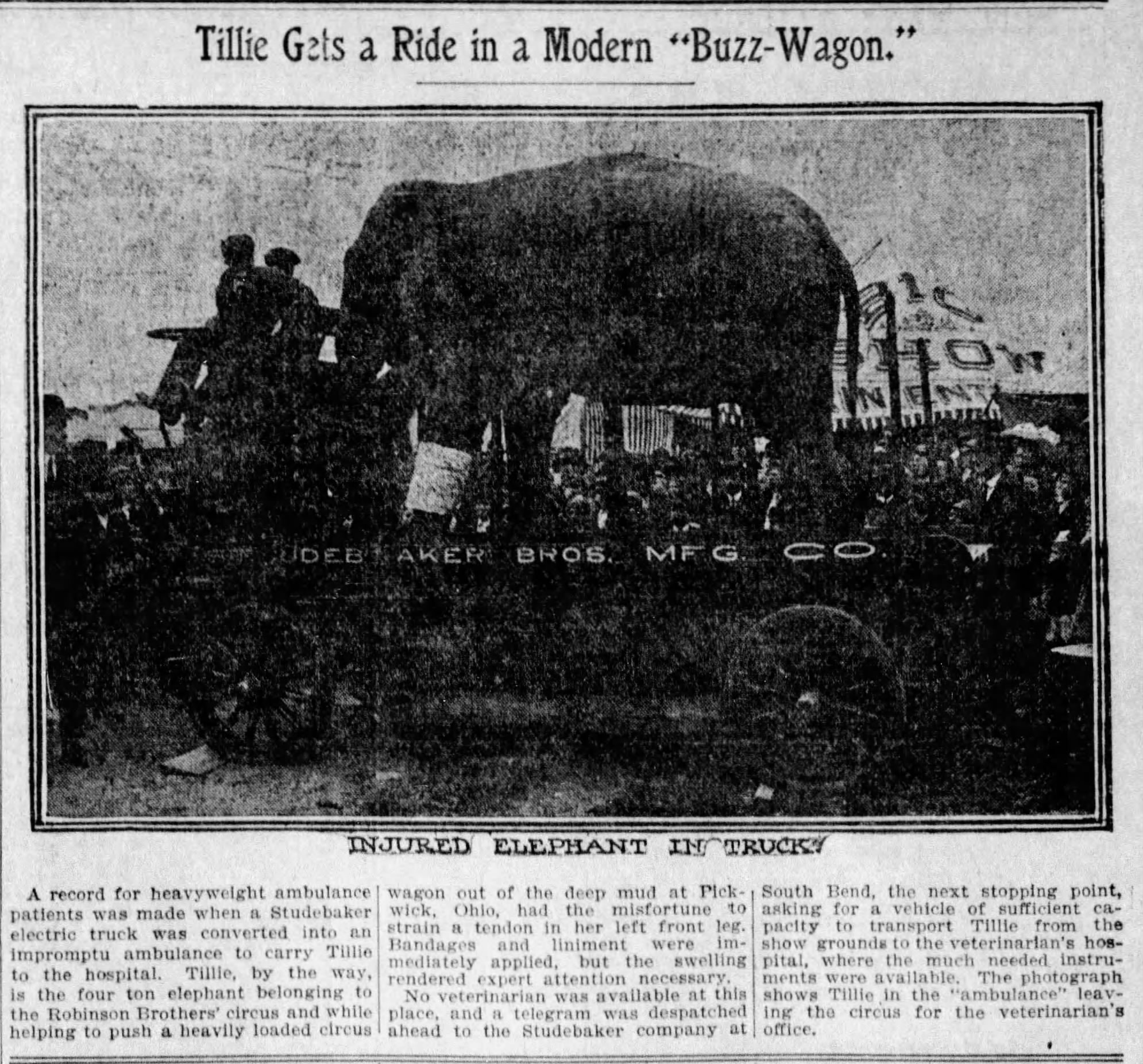

Studebaker also manufactured electric trucks and delivery wagons, with prominent companies such as American Express and Gimbel Brothers using them consistently. The U.S. Census Bureau also purchased “a 1,500-pound Studebaker electric. . . for hauling mail, supplies, and publications,” according to a 1912 issue of San Francisco Examiner. The paper noted that “the machine has been in service practically a year and has given perfect satisfaction.” Likely the most newsworthy cargo a Studebaker electric truck ever carried was Tillie, an injured elephant from the Robinson Brothers’ circus, who was transported to a veterinarian in South Bend (the circus’s latest stop) by a truck converted into an ambulance. The Oshkosh, Wisconsin-based Northwestern published a striking photograph of Tillie, with a bandaged left front leg, standing aloft an electric truck with “Studebaker Bros. Mfg. Co.” on the side. From transporting letters and telegraphs to industrial machinery and even elephants, Studebaker electric trucks and wagons played a vital role in those early years of the twentieth century.

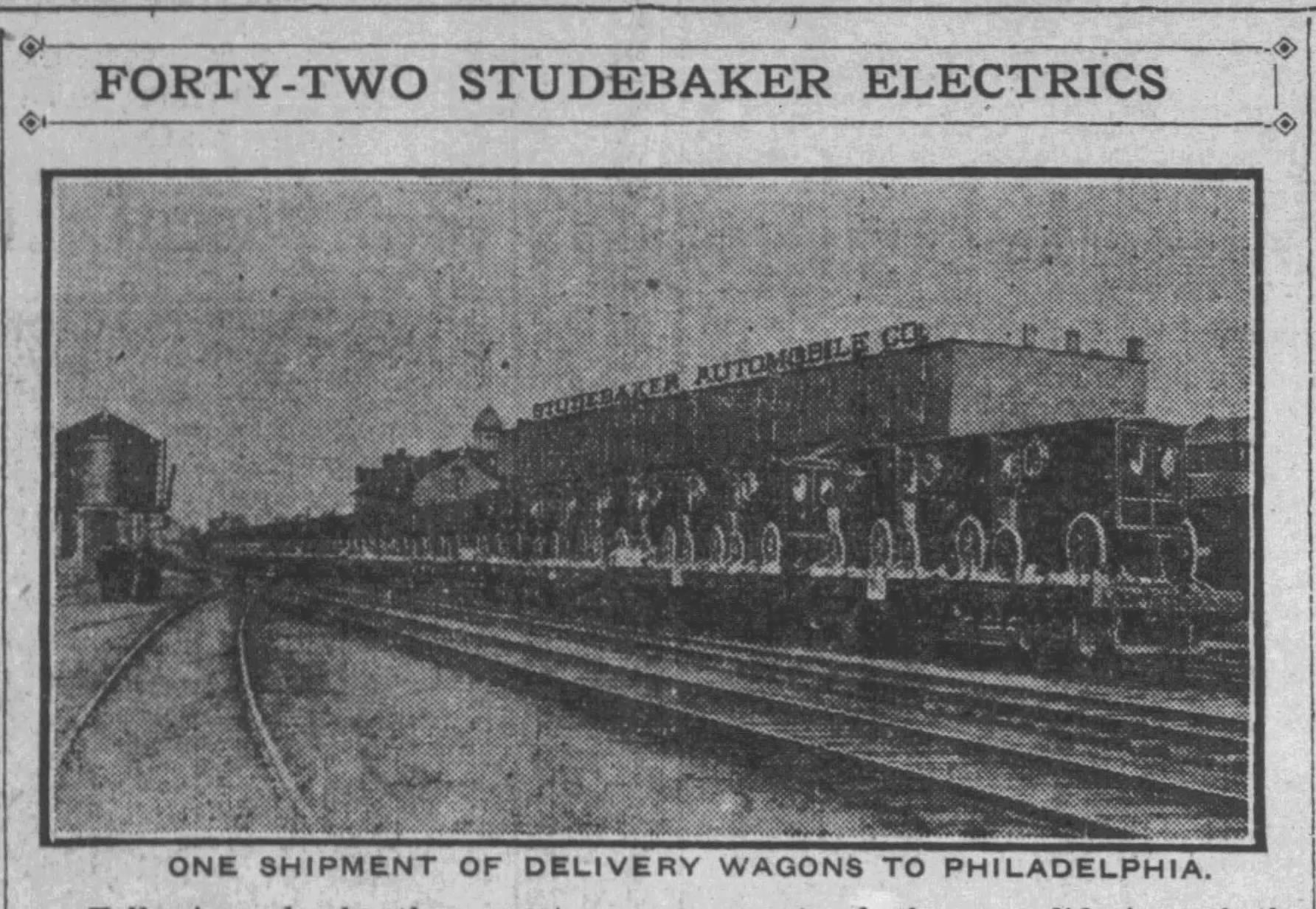

All of this leads us to a pivotal question: why did Studebaker stop manufacturing electric vehicles? The sources tell us a conflicting tale. As late as 1910, newspapers documented “heavy demand [for electrics] . . . at Studebaker’s branches in New York, Chicago, Boston, Kansas City, Pittsburg, Cleveland, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, Denver,” and the company made plans to expand its factories to accommodate the demand. However, sometime between 1911-1912, Studebaker halted production of electric vehicles. One possible explanation might have been the merger of Studebaker with the Everett-Metzger-Flanders (E-M-F) automobile company in Detroit, subsequently creating the Studebaker Corporation. Since E-M-F produced gasoline-powered automobiles, Studebaker may have seen it as more efficient to double down on existing automobile plants for its corporate expansion. As Stephen Longstreet wrote in his history of Studebaker, “there was no real future in such a slow car depending on batteries. Gasoline-powered cars were the talk in smart engineering circles.” Albert R. Erskine recorded that Studebaker discontinued production of electric vehicles in 1912, after selling 1,841 in ten years.

Furthermore, the history of automobiles indicated a significant shift towards gasoline-powered vehicles and “electric vehicles were pretty much irrelevant by the mid-1930s and would remain so for decades,” according to automotive historian Kevin A. Wilson. Significant technical challenges stalled the wider adoption of electrics, as many early vehicles were slower overall than gasoline-powered cars. “The relatively poor energy density of affordable batteries, however, kept electrics in the shade,” Wilson noted, and “advances in electric propulsion came slowly while limitations of speed and range came to look even greater in the world as it was remade by the gasoline automobile and consumers grew accustomed to long-distance highway travel at increasing velocities.”

Today, this has all changed. With the success of companies like Tesla, Rivian, and BYD, electric vehicles genuinely compete for both customers and road space, since they are just as fast, reliable, and elegant as any gas-powered vehicle. In a sense, the pioneering spirit of Studebaker and many other companies lives on in these new manifestations of electric cars.

For roughly a decade, Studebaker stood at the forefront of an electric vehicle revolution that provided affordable, durable, and reliable cars to the public. The company constantly sought to improve its vehicles through rigorous testing and innovative technological advancements, such as home charging and extended trip times. Studebaker also marketed their cars to a wide swath of consumers, from the city businessman to the society woman. And behind it all was a company based in South Bend, Indiana, that would go on to make gasoline-powered cars for decades until its dissolution in 1966.

One senses that John Mohler Studebaker, one of the original brothers who built the company from the ground up, would be pleased to see electric cars having a dramatic resurgence. Who knows? Maybe he would’ve been photographed driving a Cybertruck if he was around today. Now that would’ve been something for the newspapers.