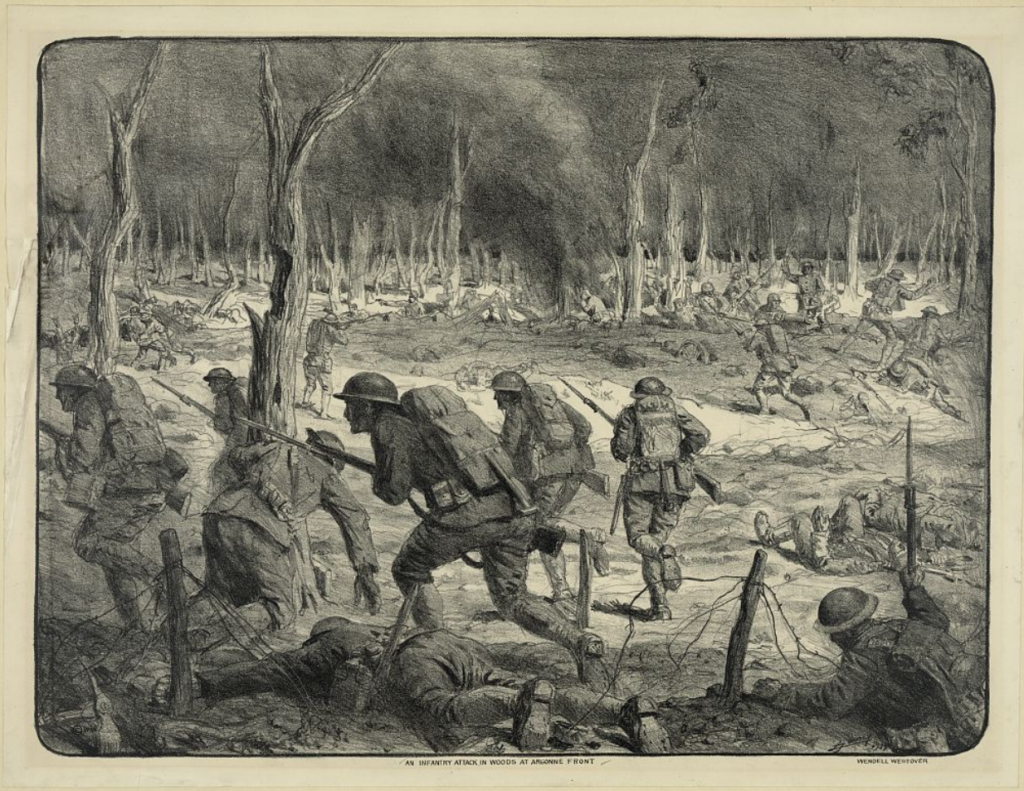

As many Hoosiers begin scheduling their vaccines, one cannot help but consider the similarities between the COVID-19 pandemic and the 1918 influenza outbreak, which spread through the state barely more than 100 years ago. The 1918 pandemic was initially confined to soldiers in Indiana bunking together in close quarters as they received training and prepared for deployment during World War I. The flu quickly spread beyond those confines and, in a turn of events eerily similar to the COVID-19 pandemic, touched almost every aspect of Hoosier lives. At the beginning of both pandemics, what was once thought to be only a minor respiratory infection quickly spiraled out of the control of even the most dedicated public health officials.

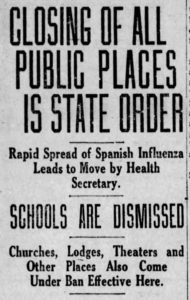

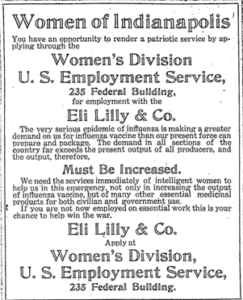

On September 19, 1918, Surgeon General Rupert Blue from the United States Public Health Service requested a report on the prevalence of influenza in Indiana.[1] Two weeks later, on October 8, known civilian and military cases within Indianapolis had already exceeded 2,000. The rapid spread of influenza prompted closures of public spaces while factories stayed open to support the war effort. Local pharmaceutical business Eli Lilly & Company also remained open, with approximately 100 employees working tirelessly, if ultimately unsuccessfully, to produce an influenza vaccine to help combat the infection and prevent its spread.[2] To meet the staffing demands needed to continue production, the U.S. Employment Service published various advertisements to recruit women who could assist with the preparation and packaging of the influenza vaccine, as well as other medicinal products produced by the company.[3]

In late 1919, Eli Lilly & Company began production of a saline vaccine that was purported to treat both influenza and pneumonia. This combination vaccine was initially created by Dr. Edward C. Rosenow from the Mayo Foundation in 1918, and he put it to use extensively that year. The formula created by Dr. Rosenow was considered a “mixed, polyvalent” vaccine because it combined various types of pneumococci, streptococci, staphylococci, and influenza bacilli, all of which had been isolated from individuals with cases of influenza as well as associated complications.[4] Drawing from Rosenow’s success in combining various bacterial strains, Eli Lilly produced their vaccine using his same methods and formula. The company hoped to create an unlimited supply for distribution to the public as prophylaxis prior to each successive year’s flu epidemic.[5]

Unfortunately, the World Health Organization concluded that Dr. Rosenow, researchers at Eli Lilly, and countless others across the United States and Europe were targeting the wrong pathogens. At the time of the pandemic, influenza was believed to result from a bacterial pathogen. It was not until 1933, when researchers at London’s National Institute for Medical Research isolated the influenza virus, that scientists realized why earlier attempts to develop an influenza vaccine had failed.[6] With the identification of the causative virus and U.S. Army soldiers participating in the clinical testing, the first influenza vaccine was developed at the University of Michigan by Thomas Francis and Jonas Salk and was licensed for public use in 1945.[7]

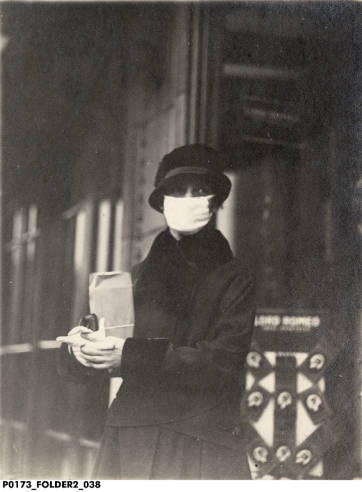

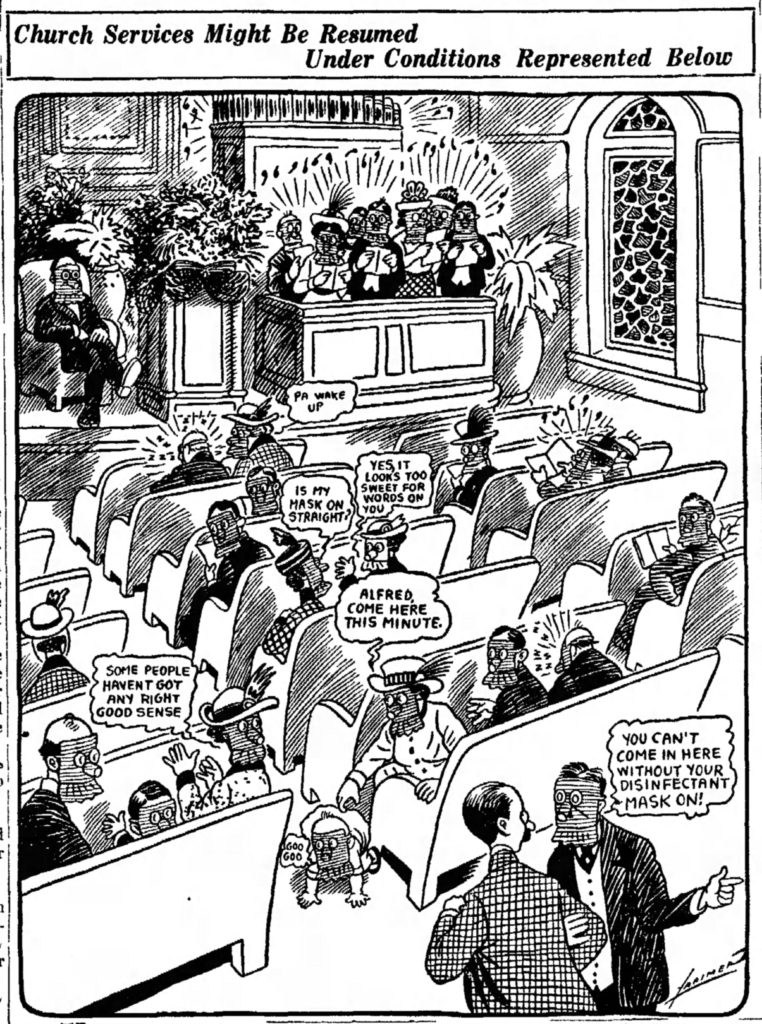

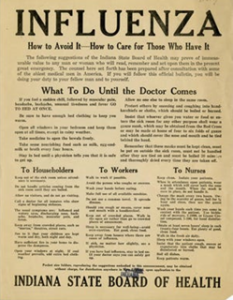

Despite the lack of a vaccine, city-wide closures kept cases within Indianapolis low. Red Cross volunteer nurses were able to be sent elsewhere in the state to assist other communities. When minor surges of influenza recurred, Indianapolis Board of Health Secretary Dr. Herman G. Morgan advocated for masking mandates and for individuals with symptoms of colds or influenza to be barred from public transportation and public spaces. He argued that mask requirements would “permit the business and social activities to continue with as little hindrance as possible.”[8]

As with the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Morgan was forced to issue a statement explaining that while he understood the masks were restrictive and bothersome, which led to much of the public outcry against them, they allowed the city to maintain as close to normal operations as possible without requiring significant closures as had been ordered months earlier. As cases decreased dramatically following these orders, the mask mandate was rescinded after only a month, and businesses were able to reopen to the public. However, the Board of Health recommended “that every care and precaution should be taken by individuals to protect their health, as the danger of infection is by no means passed.”[9]

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that approximately 50 million people worldwide and 675,000 people in the United States died due to the 1918 influenza pandemic, Indianapolis reported one of the lowest death rates in the nation, with only 290 per 100,000 people.[10] Indiana reported 3,266 total deaths, primarily among people 20 to 40 years of age, which is unusual compared to modern influenza mortality, with the highest mortality rates among young children and the elderly.[11] It is argued that such success was due to the coordinated efforts of city officials, who presented a united front for controlling the disease and explaining their positions clearly and persuasively to the public, even in the face of challenges from local business owners.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Indianapolis’s fight against the flu pandemic was the relative lack of knowledge regarding appropriate treatments for the condition. While in 2023, vaccines, antivirals against influenza, and antibiotics to treat opportunistic bacterial infections are standard practice, individuals during the 1918 influenza pandemic sought help wherever it could be found, whether from a physician, homeopath, naturopath, practitioners of traditional medicine, or others.[12]

In the early 1900s, there was far less distinction between traditional practices and medical science, and the most significant concern was to prevent or treat the illness by drawing on known characteristics of components used in formulations to treat other conditions. However, these treatments, such as mercury, arsenic, and strychnine, were not always safe or effective and often bordered on dangerous or even fatal. Medical professionals today advise a very different course of action, arguing that simple hydration, supportive care, and staying in quarantine are the best remedies against the infecting influenza virus and preventing its spread to others.

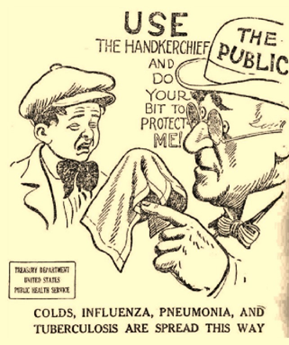

Although Surgeon General Blue mentioned some successes in other countries regarding the use of “salts of quinine and aspirin” to treat acute attacks, he and Dr. Morgan encouraged individuals to follow “ordinary rules of good health” and cover their noses and mouths when coughing or sneezing rather than making any recommendation in favor of a specific medication or pharmaceutical remedy.[13] He, along with Dr. John Hurty, Secretary of the Indiana State Board of Health, also warned against alleged manufactured or homemade “cures” for the disease, recommending that individuals be aware of potential scams and instead focus efforts on avoiding people exhibiting signs or symptoms of infection.[14]

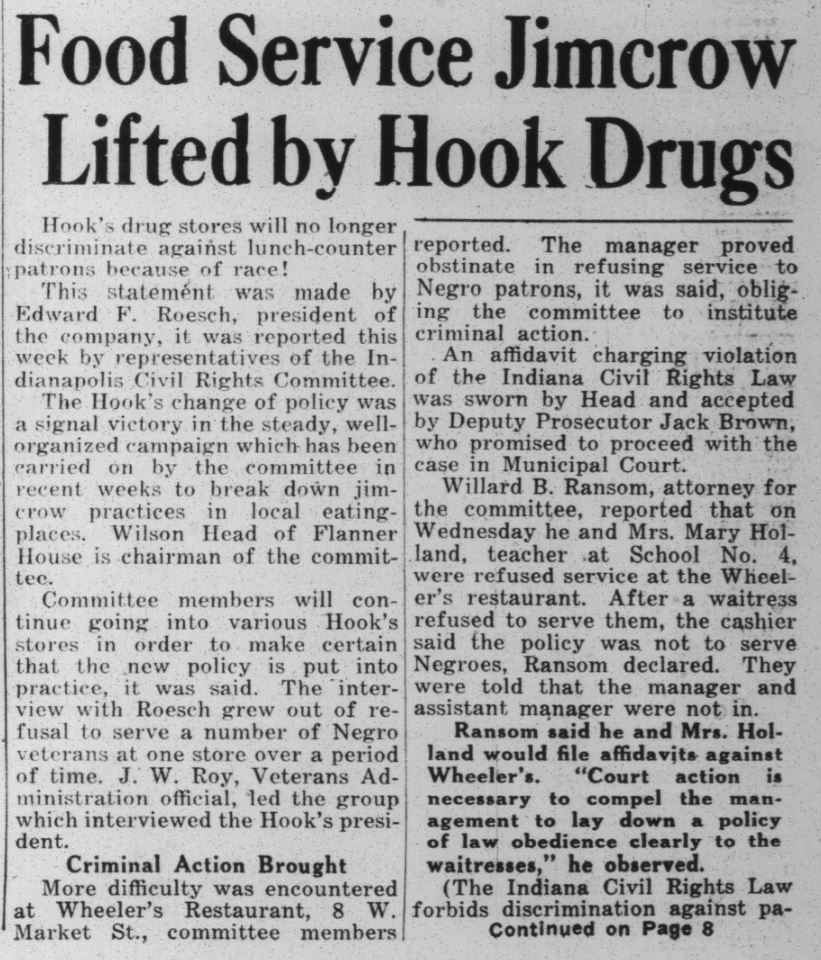

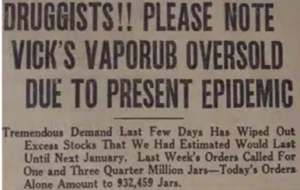

One “treatment” that gained popularity in Indiana during the 1918 influenza pandemic was Wilson’s Solution or “Anti-Flu,” developed as a preventative treatment for the Spanish Influenza. This product was developed by Robert C. Wilson, a college professor and head of the department of pharmacy at a southern university in Georgia. Consumers were encouraged to use a couple of drops of Wilson’s Solution on a handkerchief, which could then be carried with them and inhaled “when entering crowds or public places.”[15] It was believed that the antiseptic properties of the Solution’s vapors would kill the influenza germs in the nose and throat. Wilson’s Solution was sold by local drug stores in Indiana and distributed by Kiefer-Stewart, a wholesale drug firm in Indiana. Local druggists reported that this drug was difficult to keep on shelves due to high demand. Although the exact components of the Wilson’s Solution are unknown, Wilson’s Solution still in use today as a sinus rinse to treat sinusitis and chronic rhinosinusitis.[16] Regardless of what the product contained, it was marketed only as a preventative therapy and not as a cure for influenza. Consumers who contracted the flu were advised to contact their doctor immediately.

One such treatment that has gained attention for its potential role in increasing mortality during the 1918 influenza pandemic is one that many Americans today regularly take for its cardiovascular benefits – the seemingly benign aspirin. As a licensed pharmacist, I was trained in school about the concerns associated with administering aspirin to children for whom there is a suspicion of a viral illness, such as chicken pox or influenza, due to a risk of Reye syndrome. This can initially manifest as personality changes or recurrent vomiting before progressing to coma or death with associated brain swelling and fat accumulation in the liver. For adults, toxicity usually presents as abnormal consciousness and respiratory distress.

Recommendations for limiting dosing and frequency of aspirin were lacking in 1918, which likely contributed to otherwise healthy young adults succumbing to influenza.[17] Given the lack of sophisticated medical knowledge at the time to distinguish drug toxicities from general illness, it is therefore unsurprising that aspirin overdose was not linked to influenza as a contributing factor in the deaths of individuals in Western countries.

As medical science advances, new knowledge of diseases and safe and effective treatments emerge. The hope is that medical professionals and the public learn from the past and continue to seek answers to questions that once seemed to have no possible solution. In 2020, Eli Lilly was once again at the forefront of a pandemic, undertaking the “world’s first study of a potential COVID-19 antibody treatment in humans” by early June. The company was also integral in early Covid testing, piloting a drive-through program in Indiana.

While the 1918 flu pandemic will likely never be traced to a definitive cause for why it was one of the deadliest the world had seen until the COVID-19 pandemic, research into factors that contributed to the increased mortality is a promising avenue for building an understanding of how we might approach treatment options in the future.

For a bibliography of sources used in this post, click here.

Notes:

[1] “Indianapolis, Indiana,” The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: A Digital Encyclopedia, accessed https://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-indianapolis.html#.

[2] “Indianapolis, Indiana,” The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: A Digital Encyclopedia.

[3] “Classified Ad 11 — no Title,” Indianapolis Star, October 20, 1918.

[4] “Influenza-Pneumonia Vaccine,” (1919), American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record (1893-1922), 67 (12), 86, accessed https://www.proquest.com/docview/189108336?parentSessionId=5cr0scJFezskdS2R9pRBAIv8OzA959Vs3Dl%2FgtRdhd0%3D&accountid=7398#.

[5] “Influenza-Pneumonia Vaccine,” (1919).

[6] “History of the Influenza Vaccine: A Year-Round Disease Affecting Everyone,” World Health Organization, accessed https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/history-of-influenza-vaccination.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Flu Mask Order Stands; Option is Permissible,” Indianapolis Star, November 24, 1918, 1, accessed https://www.proquest.com/docview/374979130?accountid=7398.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “1918 Pandemic (H1N1) Virus,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, accessed https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html; Terry Housholder, “Flu Pandemic a Century Ago Hit Northeast Indiana Hard,” KPCnews.com, March 29, 2020, accessed https://www.kpcnews.com/columnists/article_3eaae40e-bfca-5b02-b7bd-4e641e452daf.html; “Indianapolis, Indiana,” The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: A Digital Encyclopedia.

[11] Housholder, “Flu Pandemic;” Jill Weiss Simins, “War, Plague, and Courage: Spanish Influenza at Fort Benjamin Harrison & Indianapolis,” Untold Indiana, July 11, 2017, accessed https://blog.history.in.gov/tag/spanish-flu/.

[12] Laura Spinney, Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World (New York: PublicAffairs, 2017).

[13] Celeste H. Jaffe, “The Spanish Influenza Epidemic in Indianapolis in 1918: A Study of Civic and Community Responses,” (Master’s Thesis, Indiana University, 1994), 44.

[14] Jaffe, 45.

[15] “Thousands Now Using Anti-Flu Treatment: New Solution Discovered By Georgia College Professor Designed To Kill Deadly ‘Flu’ Germ–First Used It To Protect Own Family–Just A Few Drops Inhaled From Pocked Handkerchief Disinfects Nose And Throat,” Indianapolis Star (1907-1922), Nov 20, 1918, accessed https://www.proquest.com/docview/751674358?parentSessionId=lfB6tV2GiV4OxiNGjM82VWZLbWGhtpwmeqKdm8Hb8bo%3D&accountid=7398.

[16] Ravneet R. Verma and Ravinder Verma, “Sinonasal Irrigation After Endoscopic Sinus Surgery – Past to Present and Future,” Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery 75, no. 3 (2023): 2694.

[17] Starko, 1407.