This has been adapted from its original August 22, 2019 publication in the Weekly View.

Was a Hoosier the inspiration behind the book that sold more copies in the 19th century than any other book except the Bible—Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1851 Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly? It’s a distinct possibility. Stowe penned the novel during a fearful time in America for persons of color. Fleeing intolerable conditions wrought by enslavement, many risked a perilous journey to the North. This was America after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which mandated that residents of free states return fleeing slaves to their masters or face imprisonment or fines. The country was at odds over the issue of slavery and as to the responsibility of individuals in protecting the peculiar institution. It appeared America was edging ever closer to being torn in two.

Moved by these events, young abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe put pen to paper and wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, hoping to appeal to the heart and conscience of the nation. The National Era serialized the narrative, with the first of forty chapters appearing on June 5, 1851. A year later it was published in book form and quickly became the most widely-read book in the U.S., selling 300,000 copies in 1852 alone. Stowe’s realistic depiction of American slavery through the character of “Uncle Tom” mobilized support for abolition, particularly in the North.

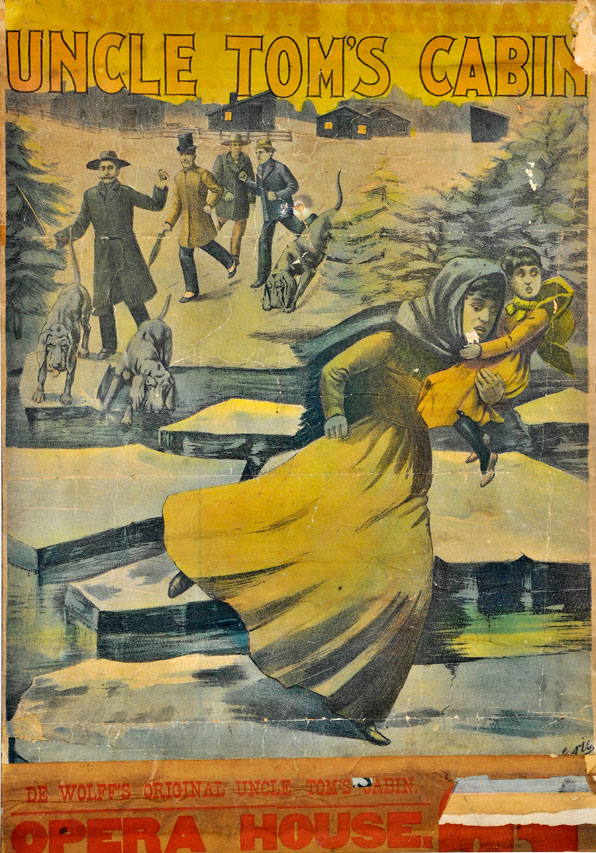

Playwrights adapted the popular story for the stage, but in doing so distorted Stowe’s original depiction of Tom in order to attract bigger audiences. Readers encountered a benevolent, but deeply convicted character, who would rather lose his life than reveal the location of two enslaved women hiding from their abusive master. The stage version depicts Tom as a doddering, ignorant man, so eager to please his master that he would sell out fellow persons of color. Dr. David Pilgrim, Professor of Sociology at Ferris State University, notes that because of the “perversion” of Stowe’s portrayal, today “in many African American communities ‘Uncle Tom’ is a slur used to disparage a black person who is humiliatingly subservient or deferential to white people.” Despite the modern implications of the term “Uncle Tom,” the Antebellum stage productions further propelled Americans to take action against the plight of enslaved people in the mid-19th century.

While Stowe acknowledged that the inspiration for Uncle Tom’s Cabin came from an 1849 autobiography, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, she’d had personal interactions with former slaves who she had met while living in Cincinnati. She was also familiar with Quaker settlements, which “have always been refuges for the oppressed and outlawed slave.” [1] In a companion book, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe documented “the truth of the work,” [2] writing that the novel was “a collection and arrangement of real incidents . . . grouped together . . . in the same manner that the mosaic artist groups his fragments of various stones into one general picture.” [3]

Although Stowe does not mention him by name, Indianapolis residents and newspapers credited a local man with influencing her book: Thomas “Uncle Tom” Magruder. Tom had been enslaved by the Noble family. Dr. Thomas Noble gave up his medical practice and became a planter in Frederick County, Virginia when his brother gave him a plantation sometime after 1782. Tom Magruder was probably one of the slaves on this plantation who, in 1795, were forced to move with Dr. Noble to Boone County, Kentucky, where he established “Bellevue” farm.

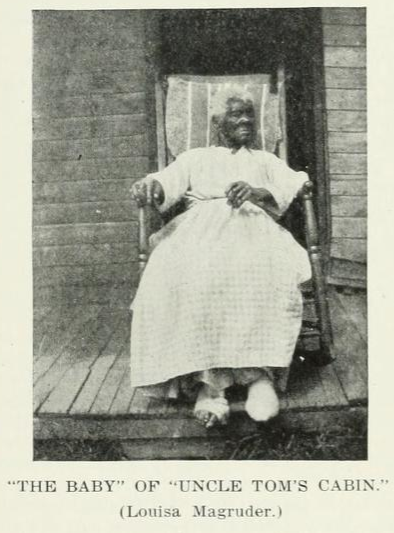

Tom managed the farm during his enslavement until 1830, when both Dr. Noble and Elizabeth Noble had passed away. He was “permitted to go free” [4] and he moved his family to Lawrenceburg, Indiana, likely to a free slave settlement. In 1831, Dr. Noble’s son, Indiana Governor Noah Noble, brought the aged Tom and his wife, Sarah, to Indianapolis. There, he had a cabin built for them on a portion of a large tract of land that he had acquired east of the city. The dwelling that became known as “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” was located on the northeast corner of Noble (now College Avenue) and Market Street. Eventually Tom and Sarah Magruder’s daughter, Louisa Magruder, and granddaughter Martha, known as “Topsy,” joined the household. Tom was a member of Roberts Park Methodist Church and was an “enthusiastic worshipper—his ‘amens,’ ‘hallelujahs,’ and ‘glorys’ being . . . frequent and fervent.” [5]

Living a few blocks from Tom at the southwest corner of Ohio and New Jersey in the 1840s was Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, white pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church. [6] He was “a constant visitor of Uncle Tom’s, well acquainted with his history, and a sincere admirer of his virtues.” [7] Like the main character in Stowe’s novel, Tom Magruder was a “very religious old Negro;” [8] of commanding appearance, his “open, gentle, manly countenance made him warm friends of all persons, white and black, who became acquainted with him.” [9]

It is known that Rev. Beecher mentioned the venerable gentleman in a sermon, which may have been when he preached on slavery on May 34, 1846. [10] Harriet Beecher Stowe visited her brother in Indianapolis that summer and may have accompanied him on one of his frequent visits to “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” It is possible that she left the city with the future title of her novel and its main character in mind. It is likely that the names of the Magruder sons—Moses and Peter—and the name of their granddaughter Topsy remained with Stowe to later find their way into her tale of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. [11]

Tom Magruder died on February 22, 1857 at about 110 years old. He was buried in the Noble family lot at the city’s Greenlawn Cemetery. At the time of his death, there was a universal belief in Indianapolis that “there are some circumstances which give it an air of probability” [12] that “Old Tom” is “Stowe’s celebrated hero.” [13] Among other things, “‘Uncle Tom’s cabin’ . . . was a familiar phrase here long before Mrs. Stowe immortalized it.” [14] Local papers “stood up for the claim” [15] in the immediate years after Tom’s death. The Daily Citizen wrote in April 1858, “It is believed here that Thomas Magruder . . . was the ‘veritable Uncle Tom,’” [16] and the Indianapolis News in March 1875 bluntly stated, “[Josiah Henson] is a fraud. The original Uncle Tom lived in this city and his old cabin was near the corner of Market and Noble Street.” [17]

In his 1910 book Greater Indianapolis, historian Jacob Piatt Dunn thought it unlikely that Tom Magruder would ever be confirmed as the inspiration behind Stowe’s legendary fictional character. However, he noted that “it is passing strange that none of the numerous friends and admirers of the Beechers in this city received any denial of it, which would necessarily have broken the uniform faith in the tradition.” [18] What Dunn was certain about is that nearly everyone in Indianapolis at the time knew Tom Magruder, “‘for he was noted as an exemplary and religious man and was generally respected.'” [19]

SOURCES USED:

[1] Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (John P. Jewett & Co, Boston, 1858), Part I, Chapter XIII: The Quakers, p. 54.

[2] Ibid., title page.

[3] Ibid., Part I, Chapter I, p. 5.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Jacob Piatt Dunn, Greater Indianapolis, vol. 1 (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co., 1910), p. 243.

[6] The Diary of Calvin Fletcher, vol II, 1838-1842 (Indiana Historical Society Press, 1973), p. 164, p. 340.

[7] “An Old Resident Dead,” The Indianapolis Journal, February 24, 1857, 3:1.

[8] Jacob P. Dunn, “Indiana’s Part in the Making of the Story ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin,’” The Indiana Quarterly Magazine of History 7, no. 3 (September 1911), 115.

[9] “Early Recollections. Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” Daily State Sentinel, December 31, 1862, 2:4.

[10] The Diary of Calvin Fletcher, vol. III, 1844-1847, (Indiana Historical Society Press, 1974), p. 62, p. 259.

[11] Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Life Among the Lowly (Boston: John P. Jewett & Co., 1852), title page.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Jacob Piatt Dunn, Greater Indianapolis, vol. I (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co., 1910), p. 244.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “Scraps,” The Indianapolis News, March 27, 1875, 2:3.

[18] “‘Uncle Tom’ Was Resident of City,” The Indianapolis Star, July 22, 1912, 19.

[19] Ibid.