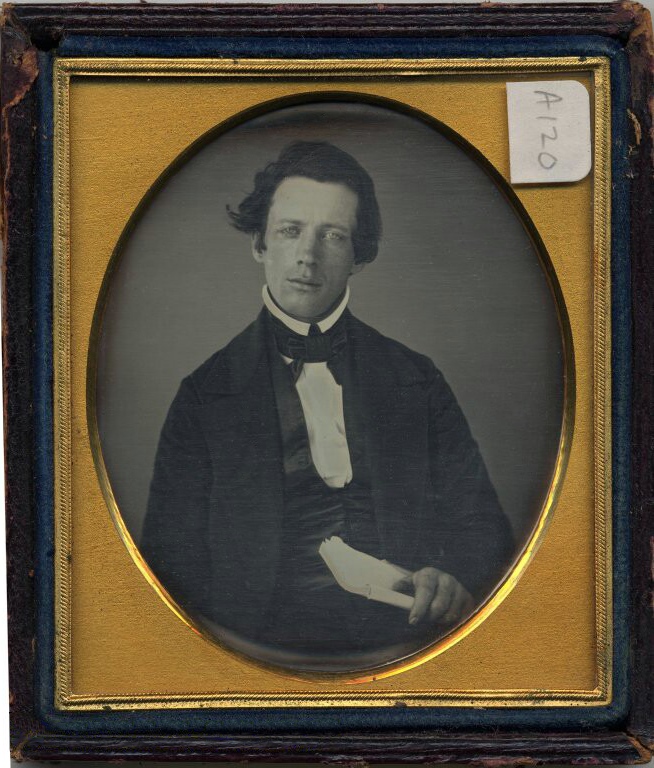

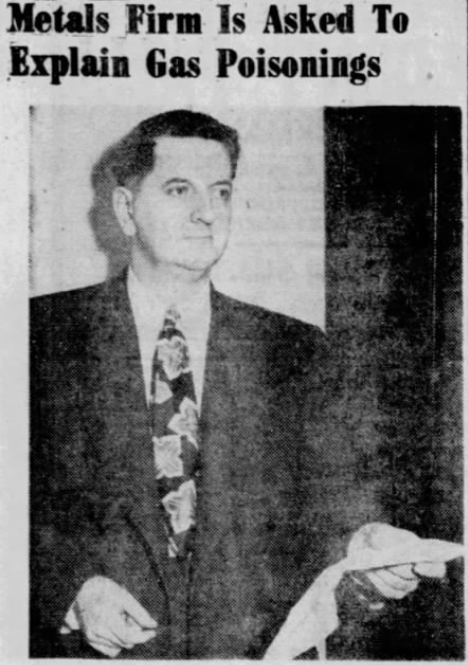

For all of human history, natural disasters have plagued the citizens of villages, towns, and nations. One such incident, the volcanic eruptions on Martinique and St. Vincent in 1902, displayed the immense destruction left in the wake of such a tragedy. As one of the few journalists allowed back to the islands after the eruptions, James P. Hornaday, Washington correspondent for the Indianapolis News, witnessed the devastation first-hand and wrote detailed articles about his experiences. In doing so, Hornaday chronicled one of the world’s most violent natural disasters and provided future scholars with a thorough rough draft of what came after.

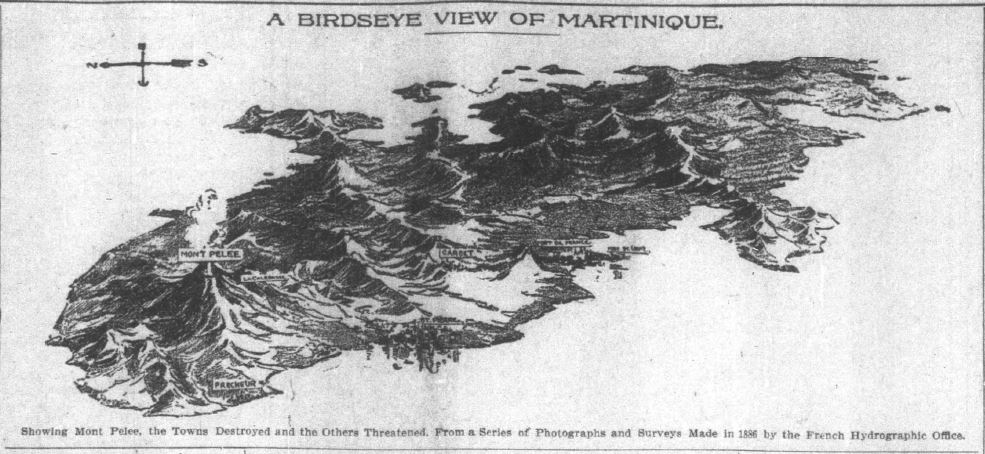

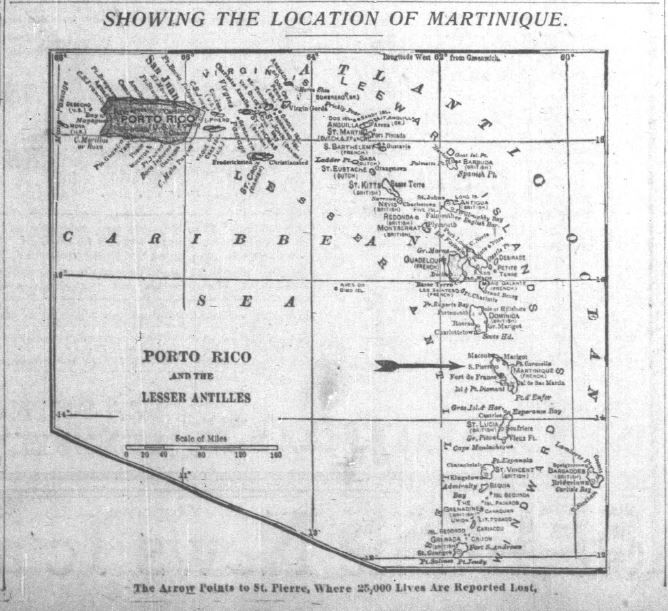

The islands of Martinique and St. Vincent served as colonial outposts in the Caribbean; the former belonged to the French and the latter belonged to the English. In particular, the Indianapolis News described Martinique as “one of the West Indies, belonging to the chain of the Lesser Antilles. . . . thirty-three miles south of Dominica and twenty-two north of St. Lucia.” St. Vincent, the largest of a chain of islands collectively known as the Grenadines, sits within miles of Martinique. Both islands contained valuable natural resources, agriculture, and industry, especially sugar. Being the creations of tectonic shifts and volcanic activity, Martinique and St. Vincent always faced the potential threat of violent eruptions. However, nearly no one in 1902 expected what carnage awaited them.

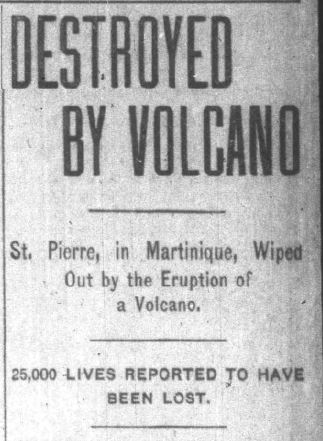

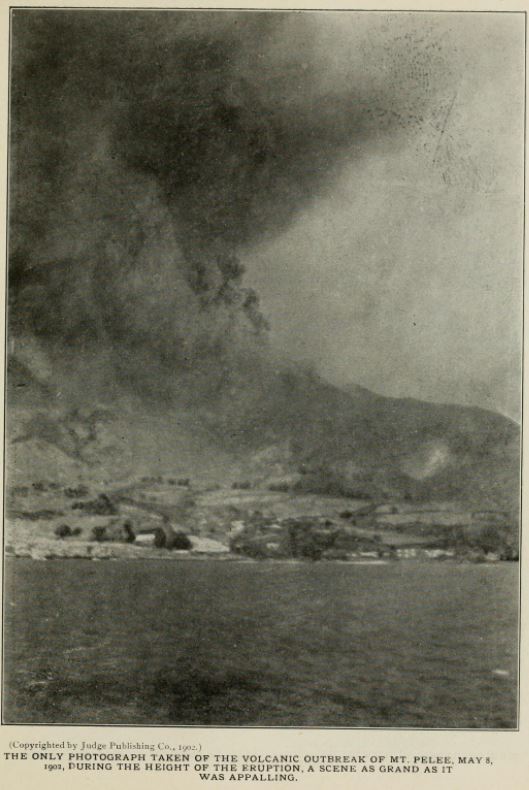

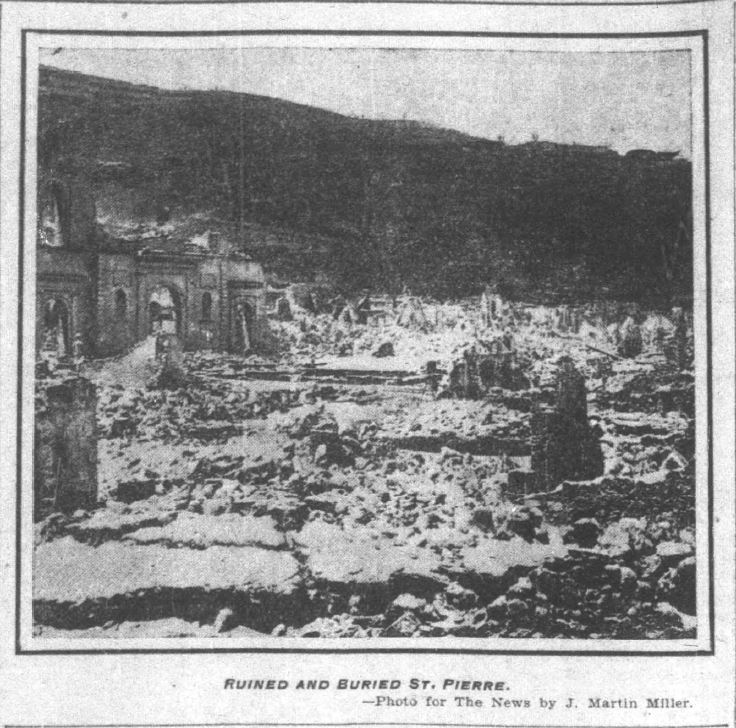

On May 8, 1902, after a few days of growing volcanic pressure, Mount Pelée spewed forth ash, rocks, and steam that completely covered the city of St. Pierre, Martinique’s population center. The News reported that St. Pierre was “totally destroyed by earthquakes and volcanic disturbances” and that “almost all the inhabitants—more than 25,000—are said to have been killed.” This left the thousands who survived “without food or shelter.” Across the way, St. Vincent’s Soufrière volcano also gained momentum, with “a big cloud of steam” lingering over the island and startling its inhabitants. The trouble for both of these islands was only beginning.

Within days, the news of Martinique’s destruction reached the ears of two prominent Indiana legislators, U.S. Senators Albert J. Beveridge and Charles W. Fairbanks. They started crafting legislation that would send relief supplies to the island, originally calling for an appropriation of $100,000. Upping the ante, President Theodore Roosevelt asked for $500,000 from Congress. They eventually settled on a compromise of $200,000 (over $5.6 million in 2016 dollars) after further negotiations in the appropriations committee led by Indiana Congressman James A. Hemenway. The president also offered his condolences to the French president, Emile Loubet. “I pray your excellency,” President Roosevelt wrote, “to accept the profound sympathy of the American people in the appalling calamity which has come upon the people of Martinique.” Additionally, his message to Congress stressed the importance of a swift relief effort. “I have directed the departments of the Treasury, of the War and of the Navy to take such measures for the relief of those stricken people as lies within the executive discretion,” he declared.

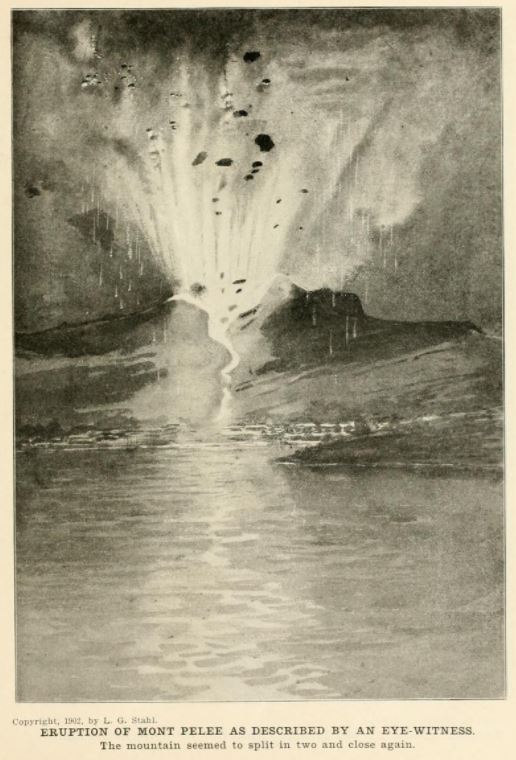

By May 12, the death toll on Martinique grew to 30,000 and the island was engulfed in “almost total darkness.” Among the living, some 50,000 people were without homes, ample food, and supplies. Nearby islands began taking in refugees, but that also came with difficulties. As one Guadeloupe civil servant said, “I do not believe Gaudeloupe [sic] can adequately relieve the stupendous distress.” The next day, the News reported that 1,600 people perished in the eruptions on St. Vincent. James Taylor, an officer on the Quebec shipping liner Roraima, shared his encounter with Mount Pelée:

Suddenly I heard a tremendous explosion. Ashes began to fall thicker upon the deck, and I could see a black cloud sweeping down upon us. I dived below, and, dragging with me Samuel Thomas, a gangway man and fellow-countryman, sprang into a room, shutting the door to keep out the heat that was already unbearable.

He also shared, in painful detail, the aftermath of the destruction:

All about were lying the dead and the dying. Little children were moaning for water. I did what I could for them. I obtained water, but when it was held to their swollen lips they were unable to swallow, because of the ashes which clogged their throats.

The Reverend William A. Maher, an Indianapolis native who frequently visited Martinique, also expressed his thoughts on the tragedy that fell upon the island. “The horror of this destruction in Martinique is appalling to me,” Maher noted, “It may be that it comes to me more strongly for the reason that some of the persons I have known may have been among the victims.”

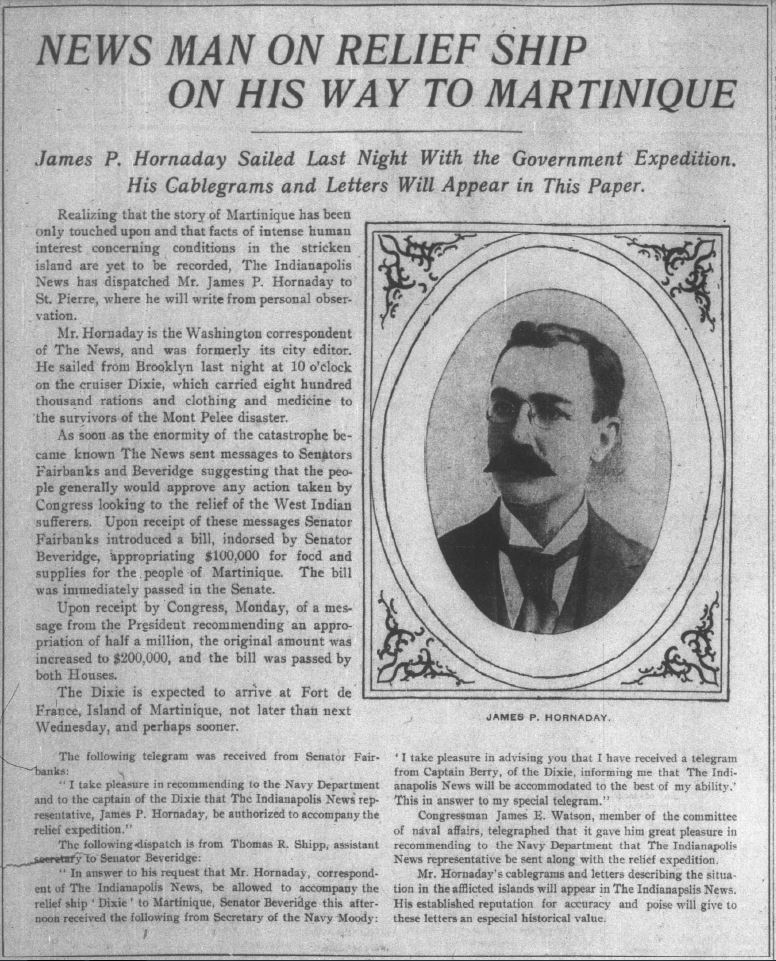

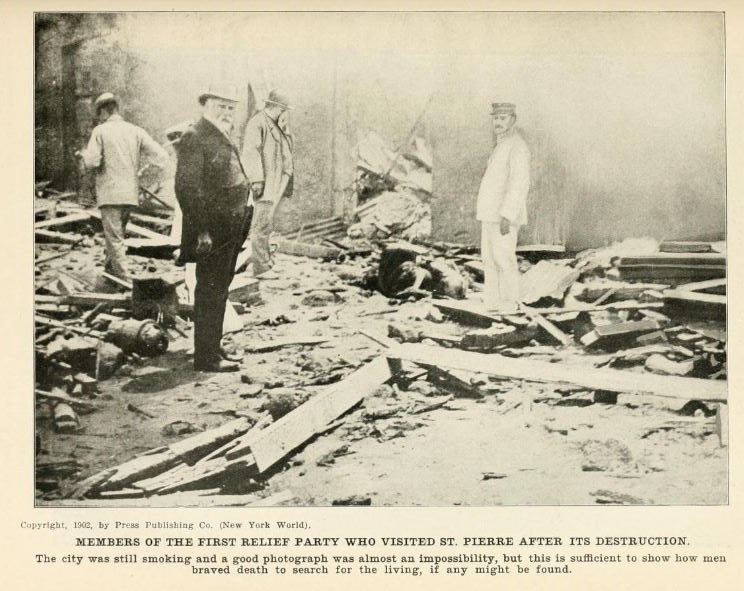

As soon as the ink was dry on the appropriations, relief ships sailed for Martinique. One such ship was the Dixie, which left from New York City on May 14, 1902. It carried thousands of pounds of food, clothing, shelter materials, and medicines. The stores were desperately needed; nearly 100,000 inhabitants of Martinique were without a steady source of food and supplies. The crew included three army surgeons, thirteen army officers, and 14 civilians, among which were geologists, explorers, volcanologists, and a small handful of press. Among the select journalists included in the crew was Indianapolis’s James P. Hornaday, Washington correspondent for the News. His inclusion came after Senator Beveridge, Senator Fairbanks, and Congressman James Eli Watson sent an appeal to the ship’s captain, Robert Mallory Berry, who allowed Hornaday to join the crew.

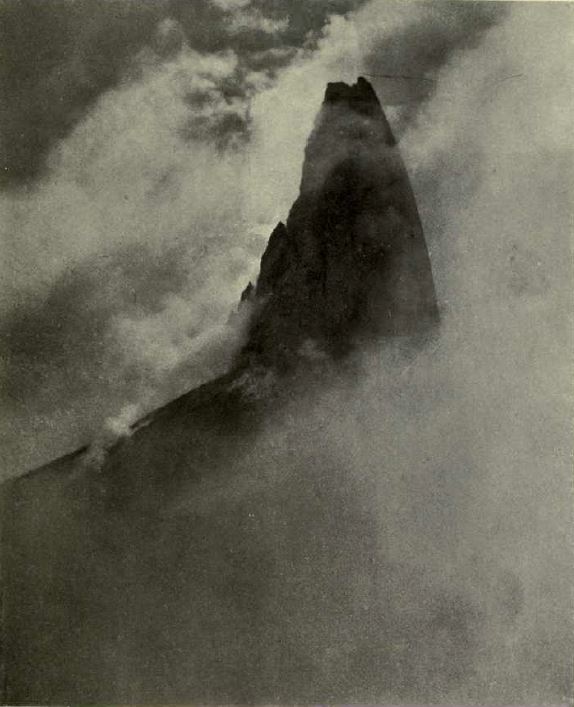

Over the next month, Hornaday wrote about his experiences aboard the Dixie and on the islands of Martinique and St. Vincent. The News ran these stories as front page features for over a week. The first article appeared on June 5, 1902, under the title, “With the Relief Boat Dixie: First Story of Uncle Sam’s Work.” Hornaday described his time on the relief vessel, learning from the eminent scientists and military personnel as well as his first glimpses of the Mount Pelée and the island. “In a little while the clouds that surrounded and obscured the volcano on the island shifted, and the crater came into full view,” wrote the newsman, “The island, containing only five square miles, looked like a great heap of volcanic debris piled up—as it really is.”

As he went ashore, Hornaday saw some of the refugees for the first time:

Thousands of refugees, with faces almost expressionless, crowded the sea line in the town of Fort-de-France. Many of them implored the strangers to take them away. To stay, they said, meant certain death.

Two small steamboats, plying the Caribbean waters, were being loaded with such refugees as could raise money enough to get away. Families carried on their heads all their earthly possessions and dumped them into these boats

As for those who stayed on Martinique, he noted their reluctance to use electricity, which resulted in the city of Fort-de-France switching from “electric lights to candles.” “The sensibilities of the natives,” wrote Hornaday, “seemed to be so paralyzed that grief could not manifest itself.”

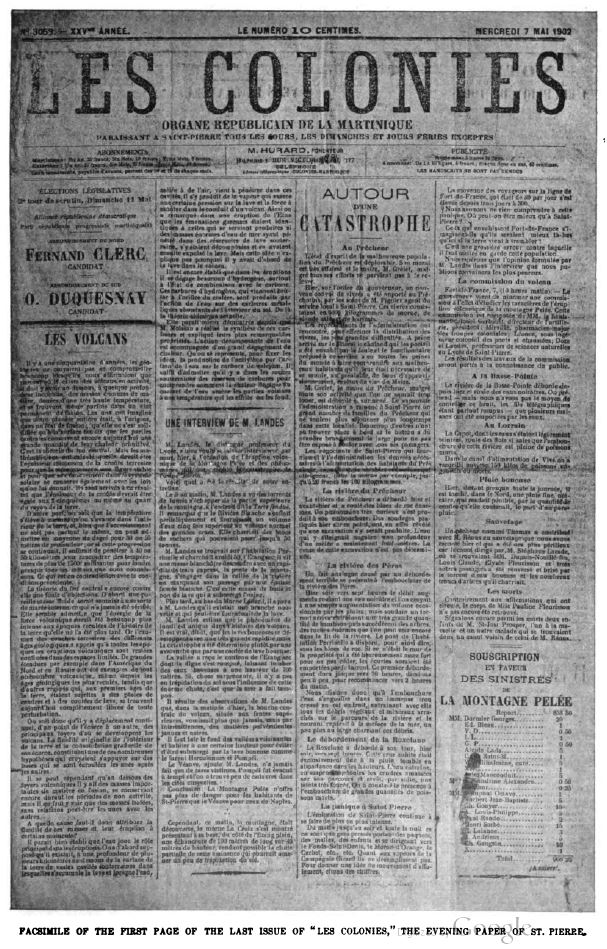

In his next article, Hornaday pieced together a rough outline of the events that resulted in the destruction of St. Pierre. Les Colonies, Martinique’s premier newspaper, served as a guide for some of his conclusions. One of the first indications of volcanic activity was reported on April 25, a full 12 days before the eruption. A “picnic guide” named Julian Romain saw what he described as “a boiling mass of what be called ‘bituminous stuff’” around the volcano. “In the cauldron of the crater I saw a boiling, black mixture of bituminous stuff, it rose up, popped, and allowed jets of steam to escape,” Romain said of his encounter with Mount Pelée. Showers of ashes emerged from the sky by May 1, which “did not reach St. Pierre, but guides returning to the summit reported that the ground was well covered high up on the side of the mountain.” May 5 brought on more steam, ash, and eventually boiling water that “formed a good river, and rushed down the mountain side.” The watery onslaught “engulfed several large sugar-cane mills and killed many persons—how many will never be known, for no record had been made up before the great disaster came.”

Two days later, a government commission published a report arguing that “Mont Pelée [sic] offers no more danger to the people of St. Pierre than Vesuvius offer to those of Naples.” The editor and publisher of Les Colonies sided with the government in an attempt to calm the island. “Since the day Jules Romain looked over into the boiling cauldron no one knows what has happened on Pelée,” the editor opined, “We only know we have been getting ashes. What has to-morrow in store for us?” As Hornaday solemnly noted, “the next morning the man who penned those lines was smothered by the escaping gas and buried beneath the ruins of his little printing office.”

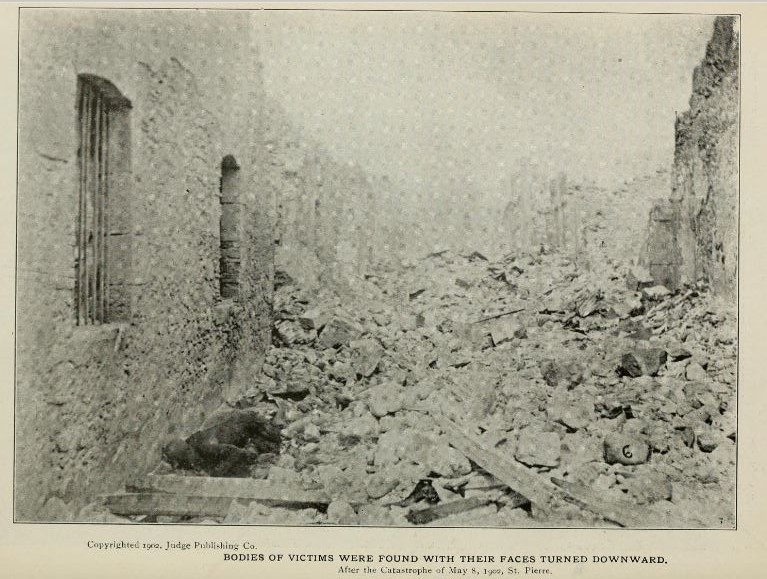

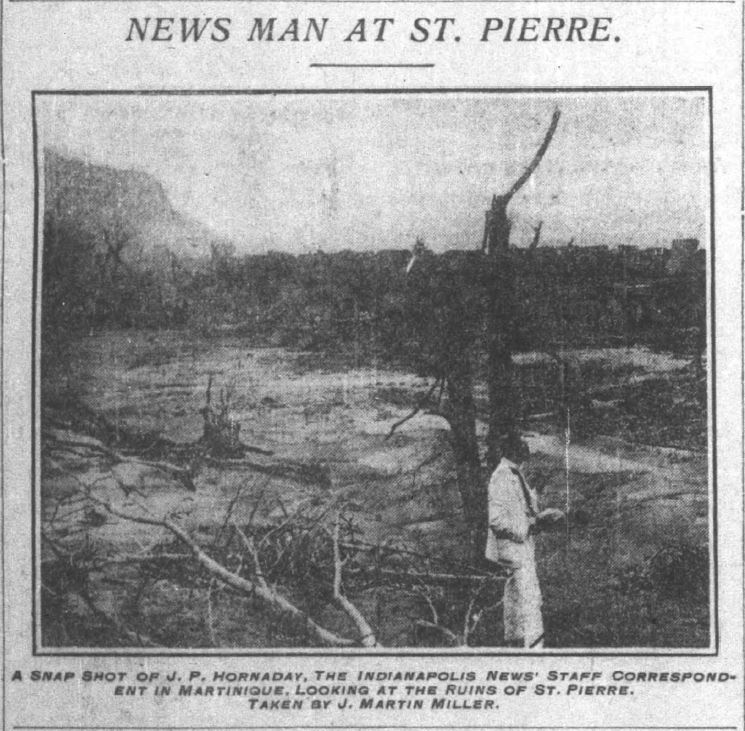

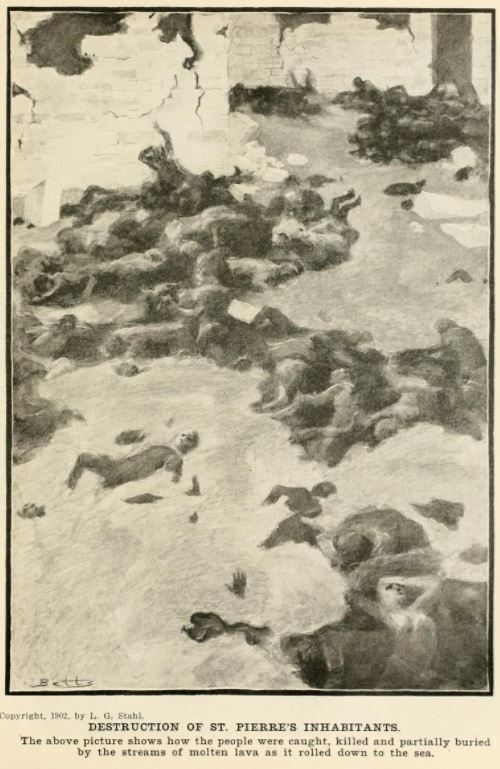

Hornaday surveyed the ruins of St. Pierre on May 22, with his reporting appearing in the News on June 7. “In a land area ten miles wide and twelve miles long every living thing was destroyed. . . . the dead were buried by the same force that destroyed the life,” he reported. As he walked around, he would eventually see Pelée and the outline of the former city. Here are some of his details:

Pelée, rising to the northeast of the city, was cloaked in gray ashes from base to summit. Here and there up the side of the mountain could be seen jets of steam issuing forth. The whole scene was one of desolation. Not a sprig of green came within the range of sight. As we drew a little nearer the beach off St. Pierre the details of the ruins stood out before us.

As for those “details,” Hornaday wrote of city buildings ravaged like “children’s blocks tumbled over” and ashes that “buried the dead to a considerable depth.” The island’s governor was reported lost in the wreckage and no attempt was made to recover his body “which, from the general appearance of the place, was buried in ten feet of debris from the building and the ashes from the volcano.” Hornaday stared death in the eyes and he and his crew left the island “happy…to put the picture behind us.”

From there, the coverage shifted from the destruction to the relief efforts. Hornaday’s article from June 9 outlined the efforts of relief workers and the response from the natives. “A whole dozen steamers had emptied their cargoes on the island within ten days after the disaster” when the Dixie and its crew arrived to deliver its supplies. During Pelée’s active eruption on May 8, a vast majority of citizens scrambled towards the north end of the island towards the city of St. Pierre. As Hornaday discovered, “practically every life in the north half of the island had been sacrificed.” Despite the seemingly good intentions of those offering help, the thousands who survived apparently saw the relief efforts in a different light. “The population, almost entirely colored, showed no appreciation of the donation of food and clothing by the United States,” Hornaday opined. By contrast, “the government and city officials, of course, did appreciate the act.”

Now, it is safe to assume that a statement such as this could be seen as prejudiced, as he singled out the natives of color from the government. In that light, Hornaday’s view on the situation is rather myopic. The people who survived had just gone through the worst disaster of their lives, one the government promised just days before would not happen. Perhaps the natives did not feel like trusting the outsiders and the governments who support them as a result. The island also suffered through an additional eruption on May 20 that reached parts of Fort-de-France, although no one died. Additionally, Hornaday reported that many of the natives felt “numb” from the entire experience, so it’s reasonable to suggest that while Martinique’s government appreciated the good intentions of relief effort, the natives had good reasons to be weary of the whole thing.

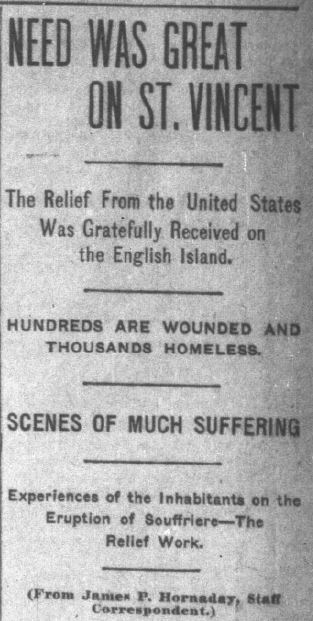

The attitude of St. Vincent could not have been more different. As Hornaday pointed out in his article from June 10, “the cruiser [Dixie] was received by the governor and the officers of the British cruisers as a friend in need, and arrangements were made at once to receive the stores.” While many died on Martinique, St. Vincent had far more injured survivors and thousands “made penniless and homeless.” While St. Vincent’s government appeared just as grateful as Martinique’s, the natives also appreciated the American relief efforts. “Everywhere one heard expressions of good will toward America for having so promptly come to the relief of the stricken people,” Hornaday highlighted. Again, this is one reporter’s view of the situation, but it is worth noting that the British island (St. Vincent) received the Americans more favorably than the French Island (Martinique). As political scientist Sidney Milkis noted, the Roosevelt administration’s relations with France did not strengthen until the second term.

After four intense days of investigation, James P. Hornaday left the island of St. Vincent on May 25, 1902 aboard the Madiana, while the Dixie stayed behind and unloaded the relief supplies. The Madiana also carried “as many wealthy refugees as she can carry,” which were described by Hornaday as “well-to-do whites.” He further noted that “the opinion was expressed by the refugees brought away that within a year many of the islands would be entirely left to the negroes.” As with his many pontifications, Hornaday comes off as wildly obtuse, if not prejudiced. Regardless, this passage is telling for one clear reason. Martinique and St. Vincent were colonial outposts, which gave their respective French and British transplants easy access off the island while the natives were left to fend for themselves. It is a case study, among many others, that documents the problematic practices of colonialism and imperialism at the turn of the century. While many non-natives perished, like the US consulate and his family, they had the easiest access to food, shelter, medical treatment, and transportation. The natives were not so lucky.

In his final article, dated June 14, 1902, Hornaday makes some tentative conclusions about the entire ordeal. He praised the “promptness with which the United States came to the relief of the needy in Martinique and St. Vincent” and that the “act touched the people of the colonies and they will not soon forget it.” That is, except those who were uneasy about American aid; this is Hornaday slightly reversing his previous conclusions, unless he is talking solely about the islands’ governments. He also praised the work of the scientific community whose initial investigations concluded “that there was ample warning from both Pelée and Soufrière” and “it is nearly always possible to foretell an eruption in time to save life.” Finally, he honored those who died in the destruction, especially American service members:

If the names of the officers and the sailors of the ships who went down could be ascertained and their families sought out wherever they may be there would be undoubtedly be an opportunity to spend wisely the relief fund which the United States holds a reserve. And since the names of most of the ships are known, it ought not to be a task beyond performance.

Once all of his articles were released, the Indianapolis News published Hornaday’s work in a pamphlet, known as the Martinique Letters, on June 19, 1902. It sold for 10 cents a copy and hailed as “a connected and comprehensive account for the great volcanic disasters.”

Sadly, Martinique suffered another volcanic upset on August 30, 1902, killing several hundred people near the towns of Carbet and Morne Rouge. One of the fatalities was Father Père Marie, who aided the scientific teams and journalists during the initial destruction on Martinique. Hornaday wrote an obituary for Mare that appeared in the News. “If the cable report be true,” he wrote, “his parishioners have perished.” Hornaday praised the priest for his kind assistance on the island during his investigations the previous May.

Martinique and St. Vincent eventually recovered from the tragedies of 1902 and the latter became an independent nation in 1979. Martinique is still a part of France but is no longer a colony; it became an “overseas department” in 1946 that grants its citizens full rights under the French government. Fort-de-France, the major city that survived the eruptions, became the capital. Their towns, villages, and economies all bounced back and both have become viable producers of sugar as well as prime tourist destinations. They have faced volcanic activity since their 1902 disasters but have always found a way to endure.

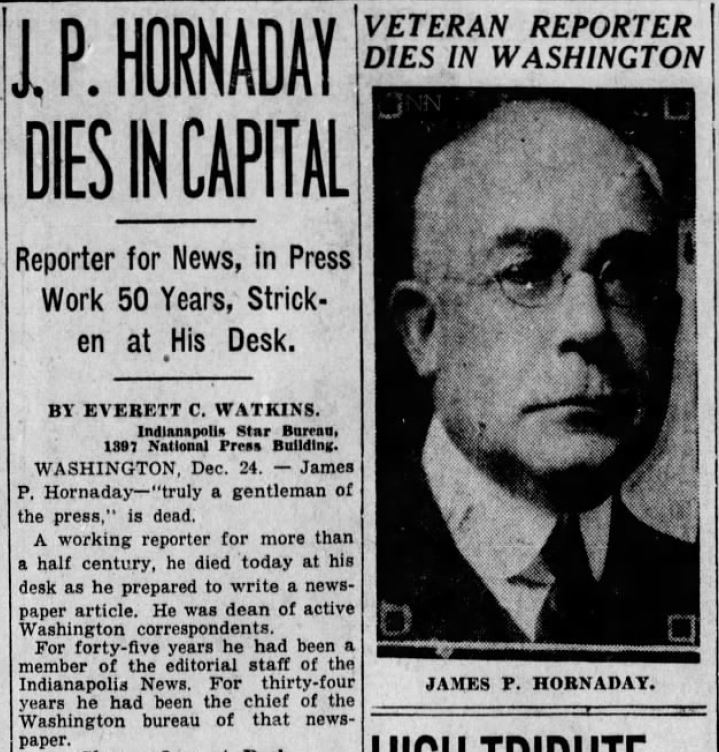

As for James Hornaday, he worked as the White House Correspondent for the Indianapolis News for another 33 years and became the Dean of White House Correspondents. He died on December 24, 1935 at his desk in Washington, writing up new stories about President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. The president released an official statement the next day:

I share with his legion of friends the grief which the passing of James P. Hornaday has brought to all of us at this Christmas time. Dean of White House Correspondents, he had through long years faithfully chronicled national events, not less admired for his talents as a newspaperman than he was beloved because of the beauty and strength of his personal character. There was, there is, among Washington newspapermen no gentler, truer soul than Jim Hornaday. We shall long remember him, and miss him, and mourn him, and be thankful that we were permitted to know him and love him.

The obituary in the Indianapolis Star also lauded the legendary newsman. Reporter Gavin Payne wrote, “I have never known a man who, in my opinion, outranked him in the sterling qualities of manhood. . . . few men have attained a higher reputation in Washington correspondence.” The article also noted his love for Indiana, saying, “He a was a true Hoosier, and though living in Washington for much more than a quarter of a century, never lost his attachment for the folks back home.”

James P. Hornaday’s articles about Martinique and St. Vincent stand among some of the Indianapolis News’ finest reporting from the period. It was also rather unique; a veteran Hoosier reporter traveled across a continent to vividly chronicle the destruction of some of the Caribbean’s most treasured islands. He helped readers then and now understand the immense geographic, political, economic, and personal struggles these islands faced in the wake of such a disaster. While some of his conclusions about the natives are out of touch with our modern sensibilities, which should be acknowledged, he nonetheless created a portrait of the event that resonates even today. He shows us what journalists will often go through to get their story, even when the world is on fire.