*This is Part One in a series about the Allens.

Marriage is complicated enough. Add in opposing political views, routinely confronting systemic racism and sexism, and coping with the hardships of the Great Depression and World War II, and it’s even more challenging. African American attorneys Elizabeth and J. Chester Allen experienced these struggles and, while theirs was not a perfect marriage, through compromise, mutual respect, shared obstacles and goals, and love, they enjoyed 55 years together as man and wife. The South Bend couple dedicated themselves to each other and to uplifting the Black community by crafting legislation, organizing social programs, creating jobs, and demanding educational equality. The opportunities the Allens created for marginalized Hoosiers long outlived them.

On his way to Indianapolis in the late 1920s, J. Chester’s car broke down in South Bend and, after staying with a family on Linden Street, liked the city so much he decided to make it his home. Or so the story goes. Elizabeth Fletcher Allen, whom he met at Boston University and married in 1928, was likely working towards her law degree back in Massachusetts when J. Chester made that fateful trip. She would eventually join her husband in Indiana, but in the meantime J. Chester quickly got to work serving South Bend’s Black community. In 1930, J. Chester was admitted to the bar and the following year was appointed County Poor Attorney for St. Joseph County.

His arrival was perhaps serendipitous, as the Great Depression had begun rendering African Americans, who were already disenfranchised, destitute. J. Chester served as management committee chairman of the Hering House, which he described as “‘the clearing house of most of the social activities of the colored people as well as the point of contact between the white and colored groups of South Bend. . . . Its activities in the three fields of spiritual, mental and physical training make it indeed a character building institution.'” Through the organization, J. Chester helped provide 4,678 meals to unemployed African Americans, along with clothes, lodging, and medical aid to others in the Black community in 1931.

In addition to providing basic necessities during those lean years, J. Chester took on various anti-discrimination lawsuits in South Bend. In 1935, he helped prosecute a case against a white restaurant owner, who refused to serve Charles H. Wills, Justice of the Peace, in a section designated only for white patrons. That same year, J. Chester served as attorney for the Citizens Committee, formed in protest to the “unwarranted shooting” of Arthur Owens, a Black 18 year-old man, by white police officer Fred Miller. The Indianapolis Recorder, an African American newspaper, noted that eleven eyewitnesses recounted that “the youth was shot by Officer Miller as he stepped from a car with hands raised, after having been commanded by the officer and his companion, Samuel Koco Zrowski, to halt.” The officers had been pursuing the car with the belief it had been stolen.

Elizabeth Allen-likely back in town temporarily-and other Black leaders organized a mass meeting to protest the “wanton, brutal and unwarranted” shooting. Despite boycotts, a benefit ball to raise prosecutorial funds, and protests by the Black community and white communists, a grand jury did not return an indictment against Officer Miller for voluntary and involuntary manslaughter. This, J. Chester said, was due to “blind prejudice on the part of the prosecutor.”

Despite a disheartening outcome, J. Chester continued to lend his legal expertise to combating local discrimination. The following year, he and a team of lawyers challenged Engman Public Natatorium’s ban on African Americans from using the facilities. The team presented a petition, likely prepared by Elizabeth, to the state board of tax commission demanding Engman remove all restrictions. Allen and other NAACP representatives had tried this in 1931, arguing that the natatorium was “supported in whole or in part by taxes paid by residents of the city,” including African Americans. Without access to the pool, they would be relegated to unsafe swimming holes, one of which led to the death of a Black youth the previous summer. While they had no luck in 1931, the 1936 appeal convinced commissioners to provide African American residents access to the pool, but only on the first Monday of every month and on a segregated basis. This was just one victory in the decades-long fight to fully desegregate the natatorium.

While it appears that Elizabeth lent her aid to certain events in South Bend, like protesting the shooting of Owen, it is tough to discern Elizabeth’s activities at this time. This is perhaps due to scant documentation for African Americans, particularly women, during this period. Likely, she was working towards her law degree at Boston University, despite being told by an admissions officer “there was not need to come and advised she get married.” Proving the officer wrong, Elizabeth not only got married, but gave birth to two children while pursuing her law degree. She attributed this tenacity to the confidence her father instilled in her during childhood and later said “’To be a woman lawyer you have to have the hide of a rhinoceros.’”

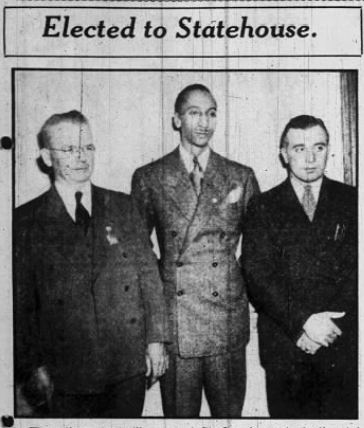

Her persistence paid off and after joining J. Chester in South Bend, she was admitted to the bar in 1938. Perhaps her presence inspired in him a sense of security and conviction, resulting in a run for the Indiana General Assembly. That year, voters elected J. Chester (D) the first African American to represent St. Joseph County. Rep. Allen introduced and supported bills that would eliminate racial discrimination in sports, the judicial system, and public spaces. The new lawmaker also endorsed bills that would require Indianapolis’s City Hospital to employ Black personnel and that would mandate appointing at least one African American to the State Board of Public Instruction, telling his colleagues “the legislature should see to it that these children had a spokesman of their own racial group to assure their obtaining a measure of equal accommodation and facilities in the segregated public school system” (Indianapolis Recorder, March 11, 1939). Writer L.J. Martin praised Allen’s unwavering commitment to serving Black Hoosiers while in public office, noting in the Indianapolis Recorder,

Hon. J. Chester Allen said he had stayed up late at night reading bills for such ‘racial traps.’ He found them, he eliminated them, one hotel sponsored bill in particular would have been a slap at the race. Mr. Allen astonishes me, in the forcible argument for racial progress.

While J. Chester walked the halls of the statehouse, championing bills that furthered racial equality, Elizabeth was able to make a difference as a lawyer. The couple opened “Allen and Allen” in 1939—the same year she gave birth to their third child. One of the first Black female lawyers in the city, and likely state, Elizabeth quickly forged a reputation as an articulate and ambitious woman. She did not hesitate to express her convictions, not even to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Elizabeth sent her a letter expressing the need to integrate housing and provide African Americans with the same government-funded housing white Americans received. Elizabeth’s son, Dr. Irving Allen, told an interviewer that Roosevelt’s response resulted in his mother’s “angry departure” from the Democratic Party. Allegedly, Roosevelt “sent back this long-winded pretentious letter rationalizing the situation . . . that the races couldn’t live together.” Both idealistic, Dr. Allen recalled that his parents’ political discourse over the dinner table “could blow up at any time.”

Elizabeth’s editorial for the South Bend Tribune, entitled “Negro and 1940,” also provides insight into her views. She lauded the “new Negro,” who:

is fearless and motivated by confidence in his belief that he owes to his race the duty of guiding those members whose minds have not been trained to clear thinking, his knowledge that the able members of his race have always from the beginning of this country contributed to the civic upbuilding and a conviction that it is up to him to keep the gains which have been made.

By this definition, Elizabeth exemplified the “new Negro,” dedicating her life to uplifting South Bend’s Black community through her work with the NAACP’s Legal Redress Committee and by organizing drives to improve housing for minorities. According to her son, Dr. Irving Allen, Elizabeth embodied the Black empowerment she wrote about, challenging oppression and advocating for those “being cheated out of a decent life.” Dr. Allen suspected that his mother also wanted to effect change as a legislator, but sacrificed her political aspirations to support her husband’s career.

Although Elizabeth felt she had to shelve her political aspirations, she complemented her husband’s legislative work, particularly regarding World War II defense employment. The outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 created an immediate need for the manufacture of ordnance. While U.S. government war contracts lifted many Americans out of the poverty wrought by the Depression, many manufacturers refused to hire African Americans. This further disenfranchised them as, according to W. Chester Hibbitt, Chairman of the Citizens’ Defense Council, an estimated 54% of African Americans living in Indiana were on relief by 1941.

And while the federal government complained of a labor shortage, J. Chester contended that “Negro workers, skilled and semi-skilled, by the thousands are walking the streets or working on W. P. A. projects, because they happen to have been endowed with a dark skin by the Creator of all men'” (“The Story of House Bill No. 445, p.15). He argued that it was the responsibility of lawmakers to prohibit employment discrimination, not only to eliminate poverty, but to safeguard democracy. Echoing the Double V campaign, Rep. Allen stated that “our first line of defense should be the preservation of the belief in the hearts of all men, black and white alike, that Democracy exists for all of us; that we are all entitled to a home, a job and the expectancy of better things to come for our children.” The continued denial of American minorities’ rights undermined the fight for freedom abroad.

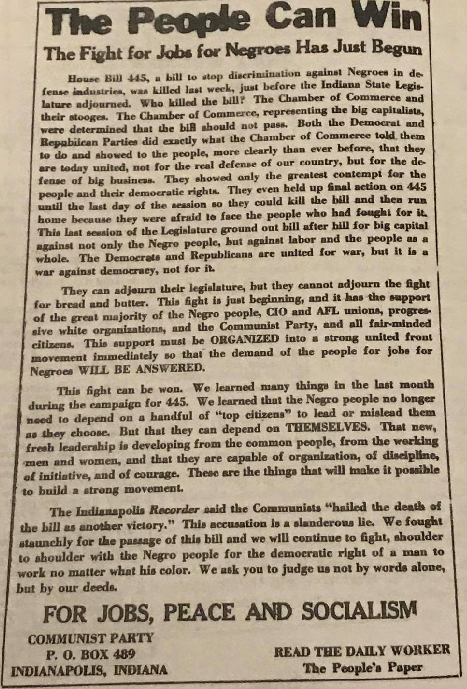

Elected to a second term in 1940, J. Chester led the call for anti-discrimination legislation. Months before President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, Rep. Allen and Rep. Evans introduced House Bill No. 445. If enacted, it would make it illegal for Indiana companies benefiting from federal defense contracts “to discriminate against employing any person on account of race, color or creed.” So popular was the bill that after the Indiana Senate passed it, delegations of African Americans and their children filled statehouse corridors and galleries, carrying “placards advocating passage of the bill, describing the measure as the only thing necessary to provide Negroes with jobs” (“The Story of House Bill No. 445”, p.7).

Despite the bill’s promising fate, on the last day of session the House kicked it over to the Committee on Military Affairs, where it essentially died. In an article for the Indianapolis Recorder, J. Chester noted that although the bill was defeated,

such state-wide attention had been drawn to the sad economic plight of the Negro workers of Indiana and its attendant dangers that people of both races agreed that the alleviation of the Negro unemployment problem was the number one job of the preparations for war of Indiana and proceeded in for right home-rule manner to do something about it.

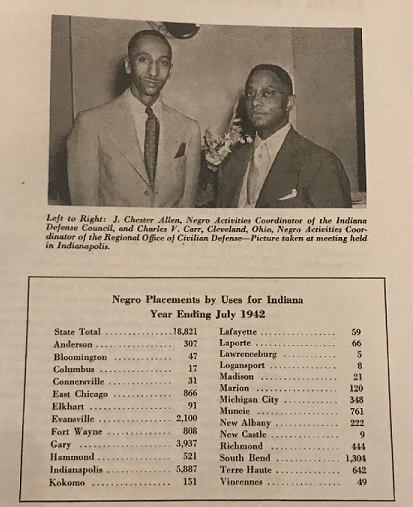

On June 1, 1941, Governor Schricker answered the call to “do something about it,” appointing J. Chester the Coordinator of Negro Affairs to the Indiana State Council of Defense. As part of the Indiana Plan of Bi-Racial Cooperation, Allen traveled throughout the state, appealing to groups like the A.F.L., C.I.O., and the Indiana State Medical, Dental and Pharmaceutical Association, which all formally pledged to employ African Americans. Through intensive groundwork, Allen established bi-racial committees in at least twenty Indiana cities.

Based on the “mutual cooperation between the employer, labor and the Negro,” the Recorder reported that these local committees would “go into action whenever and wherever Negro industrial employment presents a problem.” Although his persuasive skills often convinced employers to hire Black employees, historian Emma Lou Thornbrough noted that “Allen sometimes invoked Order 8802 and threats of federal investigation to persuade management to employ and upgrade black workers.”

Allen and the bi-racial committees also served as a sort of “middlemen” for white employers who wanted to hire African Americans, but were unsure how to recruit those best-suited for the job. Allen and the committees distributed “mimieographed questionnaires,” which provided” more valuable information with respect to Negro labor supplies, skills, etc. This information was then used with great effect in the mobilization and cataloguing of types of dependable Negro workers for local defense industries.”

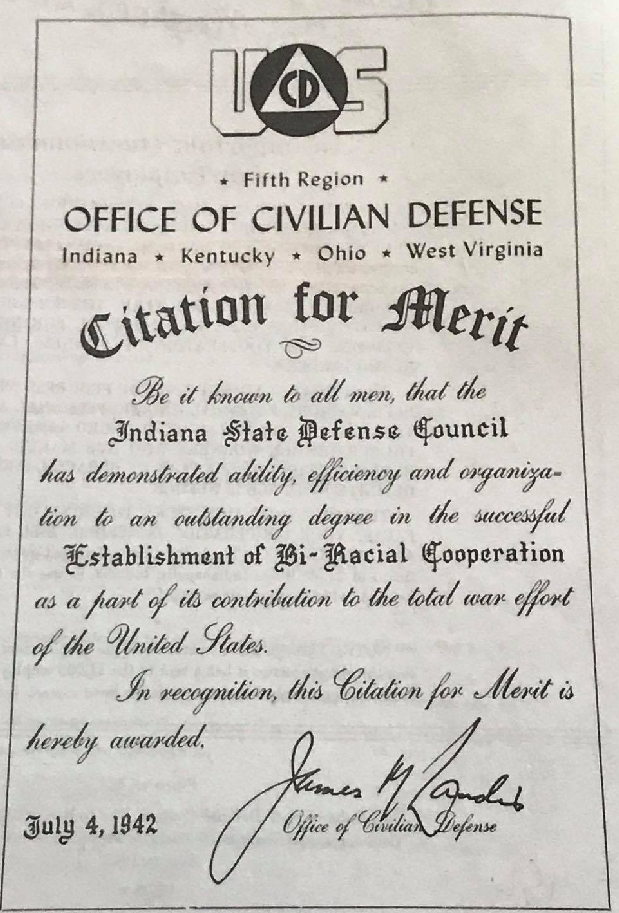

Under Allen’s leadership, the Indiana Plan proved incredibly successful, providing employment to those, in Allen’s words, “whose record of loyalty and services dates in an unbroken chain back to the year 1620” (“The Indiana Plan of Bi-Racial Cooperation,” p.5). According to the “Job Opportunities for Negroes” pamphlet, between July 1, 1941 and July 1, 1942, there “was a net increase of 82% Negro employment, most of which was in manufacturing. . . . working conditions also improved” (p.2). (It should be noted that employers continued to deny African Americans jobs in “skilled capacities.”) In fact, Indiana was awarded the “Citation of Merit” by the National Director of Civilian Defense for “outstanding work in the field of race relations.” So efficiently organized and implemented, other states used the plan as a model to bring African Americans into the workforce.

The Bi-Racial Cooperation Plan’s significance endured long after World War II ended. White employers could no longer claim that Black Hoosiers lacked the skills or competence required of the workplace or that it was “unnatural” for white and Black employees to work alongside each other. Reflecting on the program, Allen wrote in 1945, “Time was when a Negro interested in securing better employment opportunities for his people could not even obtain an audience with those able to grant such favors.” But the Bi-Racial Cooperation plan “has accomplished more for the Negro’s permanent economic improvement than had been done in the preceding history of the state.”

While African Americans were often the first to be let go from defense jobs with the conclusion of war, Allen’s work permanently wedged the door open to employment for Black Hoosiers. Allen, perhaps at the encouragement of Elizabeth, emphasized the importance of creating job opportunities for Black women and in his 1945 article noted that thousands of female laborers “have been upgraded from traditional domestic jobs, to which all colored women had previously been assigned irrespective of training or ability, to defense plants as receptionists, power-sewing machine operators, line operators and other better paying positions where their training can be utilized.”

Like her husband, Elizabeth refused to accept that Black Hoosiers would be excluded from the economic boon created by defense jobs. In the early 1940s, she established a nurse’s aid training and placement program for Black women in St. Joseph County. Of her WWII work, Elizabeth’s son said that she opened professional doors for Black women and that she saw herself as helping people who were oppressed. Like J. Chester, Elizabeth helped select local men for placement in defense jobs and, according to an October 11, 1941 Indianapolis Recorder article

used the utmost care in selecting the men to go into the factory realizing that future opportunities were dependent upon the foundation which these pioneers laid both in building good will among the fellow employes, and proving to the management that colored are reliable, trustworthy, hard-working and capable of advancing.

While J. Chester traveled the state, Elizabeth tended to the needs of the local community, chairing a drive in 1942 at Hering House for “community betterment in housing[,] social and industrial fields.” In the 1940s, Elizabeth organized various meetings to improve local housing for the Black community, emphasizing the link between substandard residences and crime rates, delinquency, and health. Deeply committed to ensuring quality education for African American children, Elizabeth founded Educational Service, Inc. in 1943, which encouraged youth to pursue social and economic advancement, provided financial aid to “worthy” students, offered individual counseling, and fostered good citizens. All of this while caring for three young children and likely manning the couple’s law office, as J. Chester fulfilled his duties with the Indiana State Council of Defense. Fortunately, Elizabeth later told the South Bend Tribune, “I want to keep busy constantly. I have to be about something all the time.”

When the war clouds cleared, the Allens achieved many of their professional and philanthropic goals. But they also experienced immense personal loss that appeared to test their marriage. Their post-war journey is explored in Part II.

Sources:

The majority of this post is based on state historical marker notes, in addition to the following:

“11,605 Helped by Hering House,” South Bend Tribune, April 22, 1931, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

“11 Witnesses Charge Police Shot too Soon,” South Bend Tribune, April 10, 1935, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Seek to Avenge Youth’s Death,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 25, 1935, 1, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

“Public Angered at Whitewash,’” Indianapolis Recorder, June 1, 1935, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

Elizabeth F. Allen, “Negro and 1940,” South Bend Tribune, October 1, 1939, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

The Indiana State Chamber of Commerce, “The Story of House Bill No. 445 . . . A Bill That Failed to Pass,” (Indianapolis, 1941?), Indiana State Library pamphlet.

The Indiana State Defense Council and The Indiana State Chamber of Commerce, “The Indiana Plan of Bi-Racial Cooperation,” Pamphlet No. 3, (April 1942), Indiana State Library pamphlet.

Mary Butler, “Mrs. Elizabeth Allen Lays Down Law to Family,” South Bend Tribune, July 30, 1950, 39, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Adult Award Winner,” South Bend Urban League and Hering House, Annual Report, 1960, p. 5, accessed Michiana Memory.

“Area Women Lawyers Tell It ‘Like It Is,’” South Bend Tribune, March 9, 1975, 69, accessed Newspapers.com.

Marilyn Klimek, “Couple Led in Area Racial Integration,” South Bend Tribune, November 30, 1997, 15, accessed Newspapers.com.

Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), p. 207.

Oral History Interview with Dr. Irving Allen, conducted by Dr. Les Lamon, IU South Bend Professor Emeritus, David Healey, and John Charles Bryant, Part 1 and Part 2, August 11, 2004, Civil Rights Heritage Center, courtesy of St. Joseph County Public Library, accessed Michiana Memory Digital Collection.