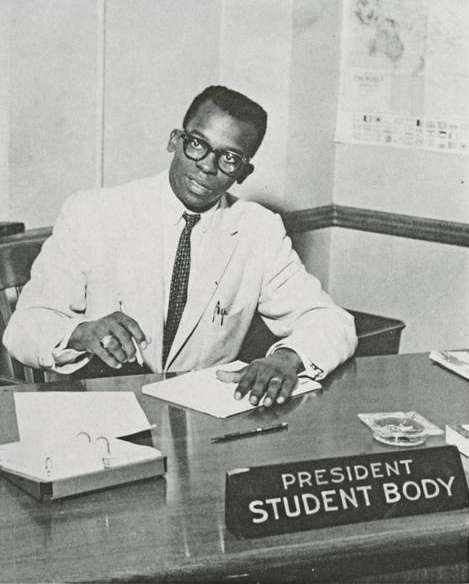

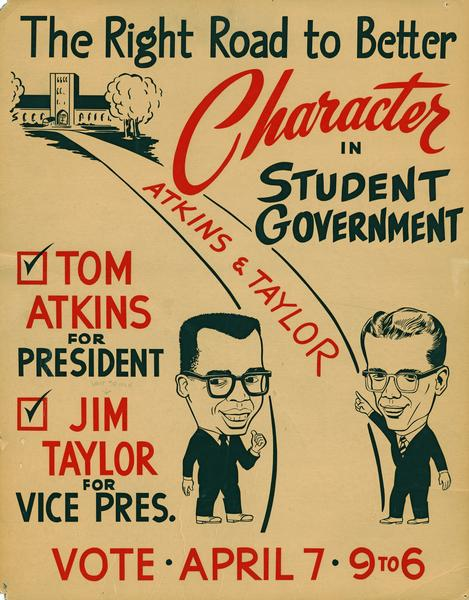

Residents at Smithwood Hall, a racially-integrated women’s dormitory at Indiana University, pelted objects from their windows on April 8, 1960. This did little to drive away the students who surrounded the building, singing segregation songs with lyrics like “Glory, glory Governor Faubus, the South shall rise again” and “Let’s all go to n****r haven.” Not until campus police arrived did the emboldened protesters finally disperse. The reason for their ire? The university had just elected its first African American student body president, Elkhart native Thomas I. Atkins. In fact, he was the first Black student to serve as president of a Big Ten school.

Protesters apparently targeted the dorm “commonly regarded as the key housing unit in campus elections” because residents voted narrowly in favor of Atkins, 388-372. As Thursday night crept into Friday morning, sisters at Alpha Phi discovered a burning cross—a signature of the Ku Klux Klan—on the white sorority’s lawn. It was rumored that some felt the sisters’ voting apathy resulted in Atkin’s victory. Under the cloak of darkness, approximately 400 students congregated at the center of campus, some waving Confederate flags and others shouting that “a bunch of beatniks” had engineered the victory. Before they could hang an effigy of Atkins, campus police broke up the protesters. The hate-filled demonstrations resumed Friday evening, when another fiery cross was found near housing for married students. Leo Downing, dean of students, noted wryly, “‘Our so-called ‘Klan element’ was really stymied in this election. . . . They either had to vote for Atkins, who is a Negro, or for [Mike] Dann, who is Jewish.'”

Atkins, described by the Indianapolis Recorder as a “mild-mannered honor student and speaker pro tem of the student senate,” responded graciously, stating he would ignore the protests as “‘not representing the Indiana University student body.'”[1] The backlash he experienced would follow him throughout his prolific civil rights law career, but his time in Bloomington helped him learn how to withstand it.

No stranger to adversity, Atkins recalled that after contracting polio at the age of five, doctors told him he would need to use crutches his entire life. Three years later, he was walking unassisted and in 1982 told the Boston Globe “‘One thing [polio] did was convince me that nothing was impossible.'” Developing tenacity at a young age served him well when Elkhart’s elementary schools “accidentally” integrated after the Black school collapsed and the town could not afford to rebuild it. Fearing for his safety, the third grader lined his pockets with rocks the first days he attended the desegregated elementary school. As a teenager at Elkhart High School, he accomplished what he would at IU: being elected as the school’s first Black student body president.

* * *

The backlash at Indiana University failed to tamp Atkins’s ambitions and the following month, the Muncie Evening Press announced he was the school’s first student to receive the U.S. Experiment in International Living grant. This allowed him to temporarily live in Turkey, where he gained insights for his thesis, “The Role of the Military in Turkish Society.” The Senior, who stayed with an Istanbul family of three, returned home in October and concluded that Turks “cannot see how the United States can propose to lead the free world and still have racial prejudice at home.” The following month he was one of three IU students nominated for a Rhodes Scholarship, which would fund three years of study at England’s Oxford University. So esteemed was Atkins that he was selected as one of twelve Board of Aeons students to advise university president Herman B Wells. In one instance, President Wells called upon him to convince discriminatory Bloomington barbers to cut Black students’ hair. Wells and Atkins convened a meeting with the barbers and, through compromise, got the barbers to agree to cut students’ hair regardless of their race.[2]

While setting himself up for professional success, Atkins made a significant and controversial decision in his personal life. Seven years before the landmark Loving v. Virginia case, in which the Supreme Court ended bans on interracial marriage, Atkins married white South Bend native Sharon Soash. Reportedly, the couple met playing with the Indiana all-state high school orchestra, and in college carpooled to the South Bend-Elkhart area from Bloomington during holiday breaks. Soash had served as Atkins’s student body campaign manger and recently graduated from IU with a history major.

So taboo was their romance, that just before the wedding one photographer staked out at Thomas’s mother’s house in an attempt to snap a picture of the couple; he was quickly rebuffed. While Soash’s father considered Atkins to be a gentleman, he tried to talk her out of the marriage. Unable to be dissuaded, they tied the knot in Cassopolis, Michigan because, according to the Boston Globe, interracial marriage was illegal in Indiana. The newlyweds planned to return to Bloomington and live in a married housing unit, where they no doubt experienced their share of harassment. Now with a spouse to consider, Atkins decided to withdraw from the Rhodes scholarship nomination process.

The South Bend Tribune reported that both Atkins planned to pursue careers in national diplomacy, a field undoubtedly in-demand during the early Cold War years.[3] Thomas was well on his way to this goal after earning a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, which enabled him to pursue graduate studies at Harvard University. While there, a Ford Foundation fellowship allowed him to train in Arabic and Middle Eastern studies and earn his Masters in 1963. In fact, the Indianapolis Star reported that Atkins earned an astonishing twelve educational fellowships, five of which were from Harvard. Despite his international ambitions, he ultimately chose to fight on the “homefront” while working towards his law degree at the Ivy League school.

That homefront was Boston, where Black parents’ charges of de facto segregation in its public school system had routinely fallen on deaf ears. Atkins turned up the volume as the local NAACP branch’s executive secretary. His knowledge of the law, appreciation of educational opportunities, and ability to withstand racially-charged backlash, made the 25-year-old an ideal advocate for the city’s Black youth. Atkins and other NAACP leaders organized a series of protests beginning in the spring of 1963, like the June 18 “Stay Out for Freedom.” In lieu of school, approximately 8,000 junior and high school students met at ten designated “Freedom Centers,” like St. Mark’s Social Center, where they discussed the Black liberation movement and learned about citizenship. The organizers’ goal was simple: get the Boston School Committee to admit that de facto segregation was present in the district. Atkins summarized “We have not asked the committee to sign away its soul in blood, but merely admit that such a condition exists.” However, the committee refused to concede this fact—and would continue to do so for years.

The assassination of Medgar Evers, a Black WWII veteran and Mississippi NAACP Field Secretary, just days prior to the “Stay Out for Freedom” event underlined the need to fight for racial equality. Atkins served as master of ceremonies at a June 26th memorial service for the slain activist at Parkman Bandstand. Over 15,000 Bostonians turned out to pay their respects and march against injustice. Recognizing that protest must be coupled with policy in order to be effective, Atkins and other leaders hosted a voter registration drive at the memorial service.

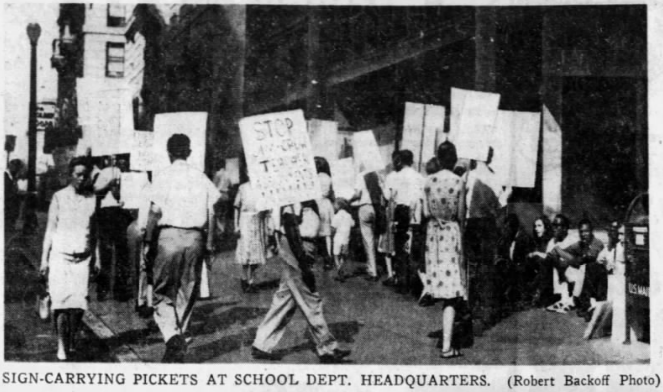

Adding to their tactical repertoire, on July 29 Atkins and other activists blocked School Committee members from entering committee headquarters, threatening to do so every day until members agree to meet with NAACP’s Education Committee. Picketers handed out pamphlets to passersby about the “deplorable conditions of the Roxbury schools” and marched carrying signs that read:

“Stop Jim Crow Teacher Assignments”

“Why No Negro Principals?”

“Would You be Patient?”

“Don’t Shoot Us in the Back”

The battle lines firmly drawn, Chairman of the School Committee Louise Day Hicks responded that “Parades, demonstrations and sit-ins may appeal to the exhibitions, but they will not help the Negro school child who everybody admits does need help.”

Fed up with being stonewalled, Atkins, on behalf of the NAACP, issued an ultimatum to the School Committee the following day, stating it had until August 2 to meet or face bigger demonstrations. Atkins wrote, “It is launched with utmost regret, for the Branch would by far prefer the relatively quiescent atmosphere of the bargaining table to the commotion and clamor surrounding a picket line.” In issuing the ultimatum, Atkins advised the School Committee to consider:

Whether they are willing to accept the moral responsibility for this demonstration and as to whether they are willing to accept the political responsibility of having another debit chalked up on an accounting sheet which already show many more debits than credits in the areas of civil rights.

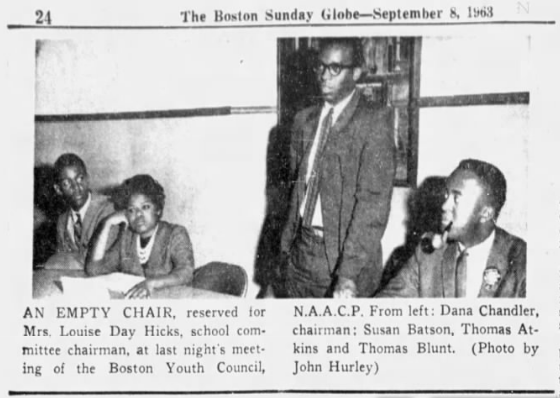

When that meeting did take place, School Committee members refused to discuss segregation. The longer the dispute went on, the more entrenched both sides grew. Although critical city officials categorized the conflict as a battle of semantics, Atkins and other leaders refused to move the goal post: without addressing segregation’s existence, equality would be impossible. Local reformer Susan Batson explained that de facto “was the most evil kind” of segregation because “no one is responsible and some say it doesn’t exist.”

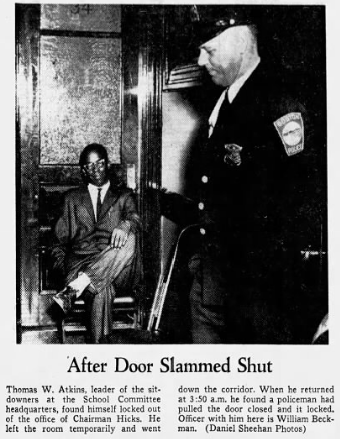

Surely, the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August—at which Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech—further empowered Boston leaders, who organized a “sleep-in” at School Committee headquarters. Such demonstrations drew the ire of committee member Joseph Lee, who called NAACP protesters “frauds, mountebanks, and charlatans.” Further, he contended:

they are clearly doing all in their power to obstruct the education of the Negro-American school child in Boston, so that they can perpetually pose as a potential Moses to lead the deprived pupil out of such imposed intellectual bondage–and at the same time pose as saviors to gull [sic?] a handsome living out of white dupers.

To these allegations, Atkins responded as he did to the IU demonstrations, with measured aplomb, stating, “I think it’s amusing.” He suggested that white residents and school committee members were shaken because “The Negro wasn’t proud of being a Negro before. Now he is. There isn’t a Negro Problem in Boston—there is a Boston problem.” But when it became clear that the committee would not recognize segregation, Atkins focused on leveraging the Black vote. If activists couldn’t get committee members to change their minds, they would change committee members.

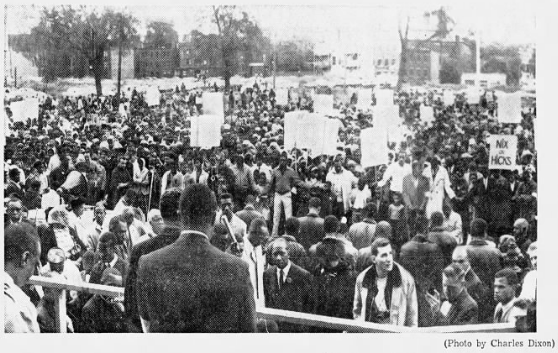

That summer, Atkins arranged for mobile registration booths to sweep the city in preparation for the elections. Before an audience of 6,000, gathered at the dilapidated Sherwin School on September 23, he urged, “Don’t complain-vote!,” foreshadowing the pleas of President Obama in 2016. Atkins framed voting as a form of self-help; to not do so would allow the school system to continue to “insult” and “ignore us.” He reminded the crowd that “Abraham Lincoln didn’t free you! He issued a document that has been studiously ignored for 100 years!” While Black and white children played on the playground, their parents sang emancipation anthems like “We Shall Overcome.” The audience also participated in a moment of silence to honor of the victims of the Birmingham bombing that took place just days earlier, another somber reminder of the injustices Black Americans faced.[4]

With all hands on deck, the NAACP branch set out to collect voters’ signatures, registering 600 new voters in the predominantly-Black Ward #12 by the time polls closed on November 2. This was double the number of new Ward 12 voters registered in 1959. Now all that was left to do was wait as the election results rolled in.

Despite all their picketing, press conferences, and political campaigning, Atkins and fellow activists were dealt a blow when voters reelected each of the School Committee members. In fact, chairman Louise Day Hicks received more votes than even the mayor. Bostonians all but confirmed they agreed with the policy of “separate but equal.” But Atkins’s ability to mobilize Black voters helped sow the seeds of enduring political activism. According to the NAACP, 80% of eligible voters in Black wards turned out to cast their ballots, a percentage staggeringly higher than the 58% turnout in Boston’s other wards.

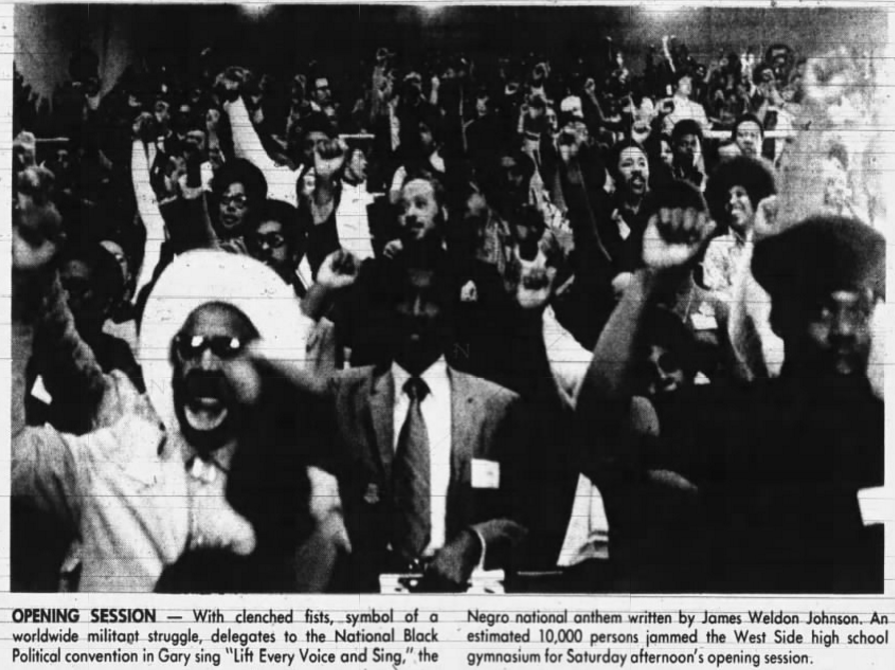

Atkins’s campaign to desegregate the school district—an effort that would require years of agitation—served another purpose, the Boston Globe noted. The city no longer looked to the South for news of the “Negro revolution.” Chants of liberation resounded in Boston’s streets, and the Globe reported civil rights is now “on the lips of cab drivers and politicians, housewives and factory workers.” The Globe added that the Civil Rights Movement is not an “accidental ripple of the national wave of protest. It is well-planned and seriously developed by a small, devoted band of persons,” Atkins, being one of them. He “has been instrumental in the carrying out of the vigorous, new approach” of the NAACP. The Boston transplant helped inspire a new militancy in the fight for Black liberation, which would culminate later in the decade with the Black Power Movement.[5]

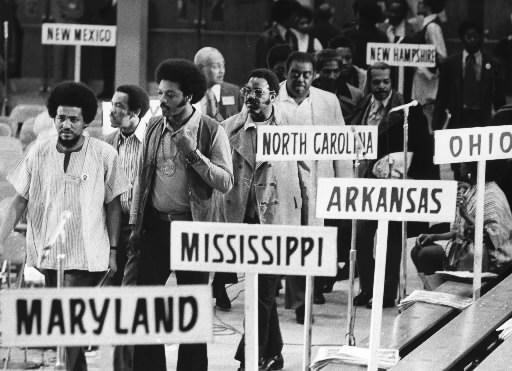

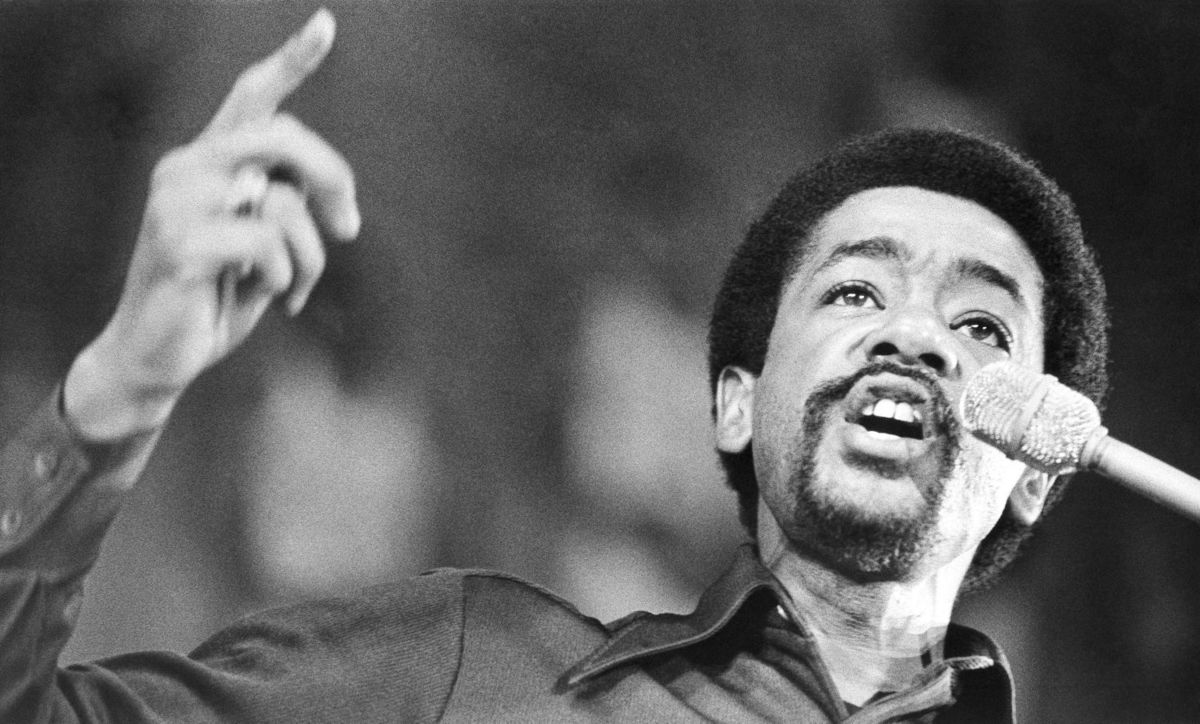

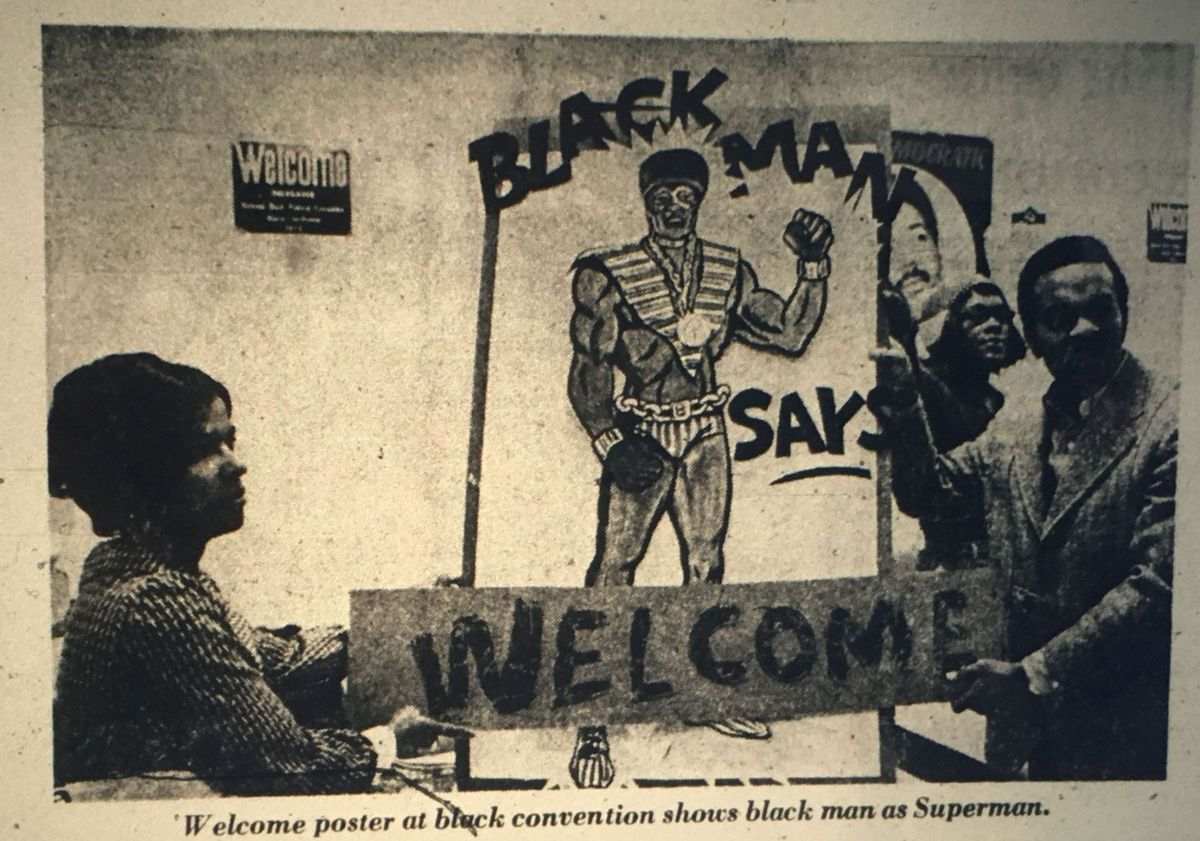

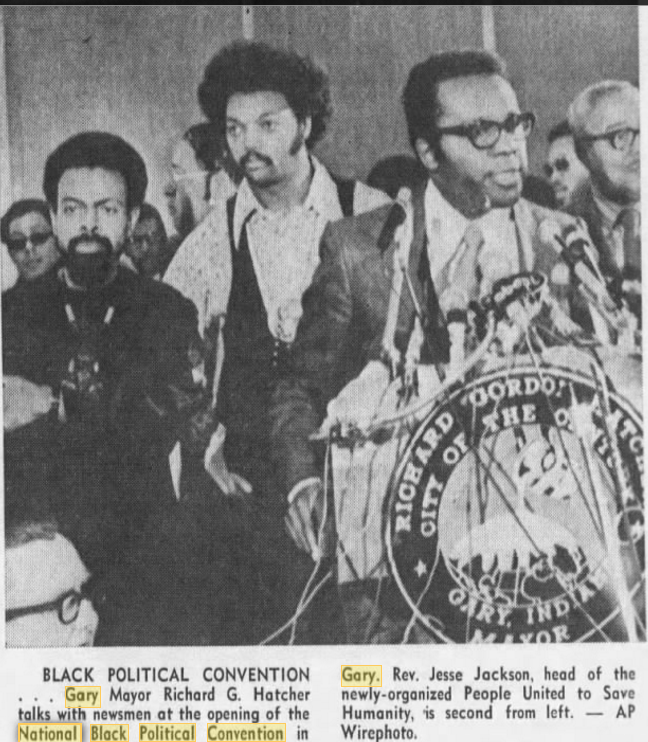

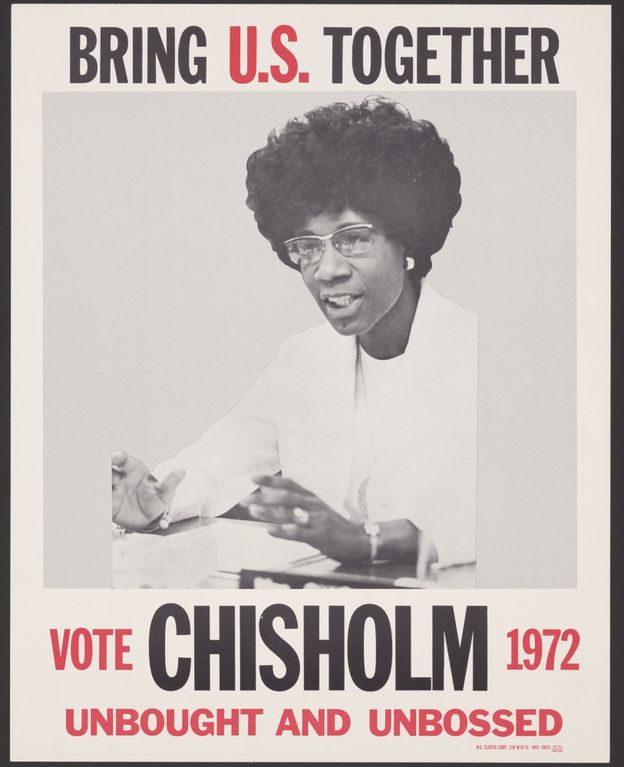

The 1963 electoral defeat hardly took the wind out of Atkins’s sails. He worked for educational and employment equality when elected Boston’s first Black city councilman in 1967. Richard Hatcher’s election in Gary, Indiana—making him one of the first Black mayors of a large US city—that same year spoke to incremental gains in political representation for African Americans. In the tumultuous year of 1969, Atkins earned his law degree and went on to become a nationally-renowned civil rights lawyer. He continued to work with the NAACP to fight for Boston’s Black students in the 1970s and 1980s, overseeing the safe implementation of busing as a means of integration. In trying to mitigate the harassment and violence directed at Black children bused to new schools, he perhaps recalled his own childhood fears of attending Elkhart’s newly-desegregated school.

An NAACP survey inquiring about the challenges South Boston High School students faced in the 1970s confirmed the inadequacy of the education they had received. Atkins recalled:

I was sitting in my office one night, and I reached into my briefcase and here were these forms. So I took them out, and I began sort of absently to read through them. As I read through one after another of these forms, what I saw was that these kids couldn’t spell. They could not write a simple declaratory sentence. And as I read these forms, none of which were grammatically correct or spelling proper, I just started to cry. It was impossible to explain the feeling of pain on the one hand, but on the other hand, I knew we were right.

Anguish spurred action and Atkins became what The Times, of Munster, Indiana, described as “one of the most active and successful civil rights lawyers in the nation.” He filed segregation suits against school systems in Hammond and Indianapolis, Indiana; Cleveland and Columbus, Ohio; Benton Harbor and Detroit, Michigan; and San Francisco. One activist noted “There’s no place where Tom Atkins wasn’t influential.” According to his son, this prolific work made him a target of death threats and ultimately he left his Roxbury home for the protection of his family. His son described Atkins “running chicken wire over windows to block Molotov cocktails and installing spigots throughout the seven-bedroom house to connect the hoses for fighting fires.” [6]

* * *

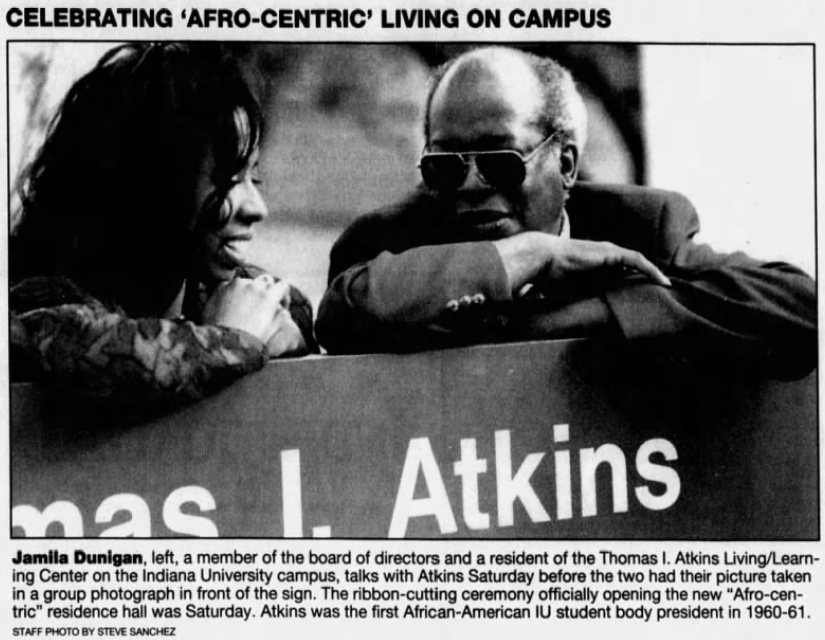

In 1994, Atkins returned to his alma mater for the dedication of IU’s new Thomas I. Atkins Living/Learning Center. On a campus once pockmarked with fiery crosses, stood a residence hall that focused on “academic excellence and cultural awareness-specifically, the culture and history of African and African-Americans.” While social progress had been made since the 1960s, racial issues persisted. The dormitory hoped to change that by facilitating discussions among various races and improve how students related to one another. With the new center, the campus also hoped to attract more Black students, an issue Atkins addressed at his 1994 visit. He said “Leadership is not made of being the first follower. . . . IU needs to get out in front and I don’t think the university has done that sufficiently. I hope IU accepts the challenge to get it done.” After all, “without education, the door is locked” to American minorities.

In his 50s, doctors diagnosed Atkins with Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was determined to overcome it through grit and hard work, as he had when afflicted with polio, stating “I believe miracles are usually man-made.” As the disease progressed, the Boston Globe noted he “continued to assist on cases even after he needed his son to translate his slurred speech and a special computer arm to help him peck out sentences.” The indomitable Atkins succumbed to the disease in June 2008, just months before voters elected Barack Obama the nation’s first African American president. His historic election came on the heels of work done by fearless leaders like Atkins, who the Boston Globe described as a “humanist” with a “steely resolve.” His time in Elkhart and Bloomington helped cultivate this unique blend of empathy and empowerment, best summarized by one of Atkins’s favorite sayings: “Power is colorless. . . . It’s like water. You can drink it or you can drown in it.” [7]

Sources:

[1] “Another Cross Burned After Negro’s Win,” The Times (Munster), April 10, 1960, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Campus Demonstration Follows Election of I.U. Negro Student,” Rushville Republican, April 8, 1960, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Segregation Demonstration Held at I.U.,” Anderson Herald, April 10, 1960, 18, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Whites Attempt to ‘Hang’ in Effigy, Negro Prexy [sic?] at IU,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 16, 1960, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[2] “3 Seek Rhodes Scholarship,” Indianapolis Star, November 6, 1960, 18, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Foreign Study Grant to Indiana Studied,” Muncie Evening Press, May 27, 1960, 7, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Thomas I. Atkins, Rights Champion and City Councilor, Dies,” Boston Globe, June 29, 2018, 16, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Turks Believe Race Prejudice Moral Question,” Indianapolis Star, October 3, 1960, 22, accessed Newspapers.com.; Andrew Welsh-Huggins, “Atkins a Campus Activist since 1960,” Times-Mail (Bedford), November 20, 1994, 25, accessed Newspapers.com.

[3] Erin Moskowitz and Mark Feeney, “Civil Rights Trailblazer Atkins Dies at 69,” Boston Globe, June 29, 2008, accessed Boston.com.; John H. Gamble, “Atkins and Bride Look to Career,” South Bend Tribune, January 1, 1961, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Parents Against Mixed Marriage,” Terre Haute Tribune, January 1, 1961, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Student Leaders in Interracial Nuptials in Mich.,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 7, 1961, 7, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.; “Thomas I. Atkins, Rights Champion and City Councilor, Dies,” Boston Globe, June 29, 2018, 16, accessed Newspapers.com.; “White Girl Marries Negro I.U. Leader,” South Bend Tribune, December 31, 1960, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[4] “14 Get Wilson Grants at N.D.,” South Bend Tribune, March 13, 1961, 16, accessed Newspapers.com.; “15,000 to Mourn Evers Here,” Boston Globe, June 26, 1963, 7, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Atkins Named Director of Federal Bank,” South Bend Tribune, January 9, 1980, 16, accessed Newspapers.com.; Boston Globe, July 29, 1963, 1, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.; Boston Globe, June 17, 1963, 1, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Elkhart Native Seeks Boston Mayoral Bid,” Indianapolis Star, May 13, 1971, 13, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Fellowship to Elkhartan,” South Bend Tribune, June 1, 1962, 20, accessed Newspapers.com.; Ian Forman, “De Facto Sleeping Giant in Mrs. Hicks’ Smash Win,” Boston Globe, November 6, 1963, 1, 29, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Hub School Boycott Planned by Negroes,”1963 Year of Ferment for Negroes in Boston,” Boston Globe, December 25, 1963, 43, accessed Newspapers.com; Boston Globe, June 13, 1963, 12, accessed Newspapers.com.; Robert L. Levey, “Does Bias Win Votes in the Hub?,” Boston Globe, August 20, 1963, 11, accessed Newspapers.com.; Robert L. Levey, “‘Don’t Complain-Vote,’ Atkins Urges Negroes,” Boston Globe, September 23, 1963, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.; Robert L. Levey, “How Hub Negro Protest Gains,” Boston Globe, December 8, 1963, 75, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Mrs. Hicks Asks Brooke Help Halt School Boycott,” Boston Globe, June 14, 1963, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.; Richard J. Connolly, “New Demonstrations Due: Hot Words Fly in Sit-In Fight,” Boston Globe, September 8, 1963, 1, 22-25, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Some 3,000 Boston Negro Pupils Boycott Classes in Mass Protest,” North Adams Transcript (Massachusetts), June 18, 1963, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Text of a Statement Read by Thomas Atkins, Executive Secretary of the Boston Branch NAACP, Concerning Direct Action to Be Taken Against the Boston School Committee,” July 30, 1963, Boston Public Schools Desegregation Project, Northeastern University Library Digital Repository Service.

[5] Robert L. Levey, “How Hub Negro Protest Gains,” Boston Globe, December 8, 1963, 75, accessed Newspapers.com.; “N.A.A.C.P.: Vote on ‘Racial Basis,” Boston Globe, November 6, 1963, 29, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Political ‘Consciousness’ is Sweeping Negroes,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 2, 1963, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

[6] Associated Press, “Negroes Win Many Races,” Spokane Daily Chronicle, November 8, 1967, accessed Google News.;”Discrimination Charges Aired,” The Times (Munster, IN), August 8, 1978, 17, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Education for Blacks is Issue–Not Busing,” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN), September 9, 1981, 9, accessed Newspapers.com.; Felicia Gayle, “Integration Suit Begins,” The Times (Munster, IN), July 27, 1979, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.; Steven Hansen, “Activist Profiled,” The Times (Munster, IN), August 24, 1978, 11, accessed Newspapers.com.; Eric Moskowitz and Mark Feeney, “Civil Rights Trailblazer Atkins Dies at 69,” Boston Globe, June 29, 2008, B3, accessed Newspapers.com.; “NAACP Lawyer Faces Arrest,” South Bend Tribune, July 26, 1978, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.; “New Boston Councilman,” Indianapolis News, November 9, 1967, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.; David M. Rosen, “Boston May Call in U.S. Marshals,” The Republic (Columbus, IN), October 8, 1974, 13, accessed Newspapers.com.; Howard M. Smulevitz, “IPS Desegregation Plan Calls for Busing of 41,000 Pupils,” Indianapolis Star, November 14, 1978, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.; Howard M. Smulevitz, “Ohio Decisions Seen Lending Weight to Dillin’s Busing Stand,” Indianapolis Star, July 3, 1979, 9, accessed Newspaper.com.; Transcript, “The Keys to the Kingdom (1974-1980),” Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1985, accessed PBS.org.

[7] “A Boston Pioneer and his Mark,” Boston Globe, July 1, 2008, 10, accessed Newspapers.com.; Lejene Breckenridge, “Achievements of Ex-Elkhartan Honored at I.U.,” South Bend Tribune, January 3, 1995, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.; Lauren Fagan, “Civil Rights Attorney, Elkhart Native Atkins Dies,” South Bend Tribune, July 2, 2008, B3, accessed Newspapers.com.; Eric Moskowitz and Mark Feeney, “Civil Rights Trailblazer Atkins Dies at 69,” Boston Globe, June 29, 2008, B3, accessed Newspapers.com.; Andrew Welsh-Huggins, “Exploring the Culture of Color,” and “Atkins a Campus Activist since 1960,” Times-Mail (Bedford), November 20, 1994, 25, accessed Newspapers.com.