Video credit: “Calvin Coolidge and the Washington Senators’ 1924 World Series,” White House Historical Association.

Not since 1924 has a Major League Baseball team from the City of Washington, D.C. clinched a World Series championship. [1] That year, the Washington Senators defeated the New York Giants four games to three to claim the first World Series title for our nation’s capital, in part because of Indiana native, Sam Rice. [2] The Senators returned to the Series in 1925 and 1933, but lost each. No Washington-based Major League team has made it back to the Fall Classic since then. Until now. This week, the Washington Nationals face off against the Houston Astros as they try to bring another title back to the capital.

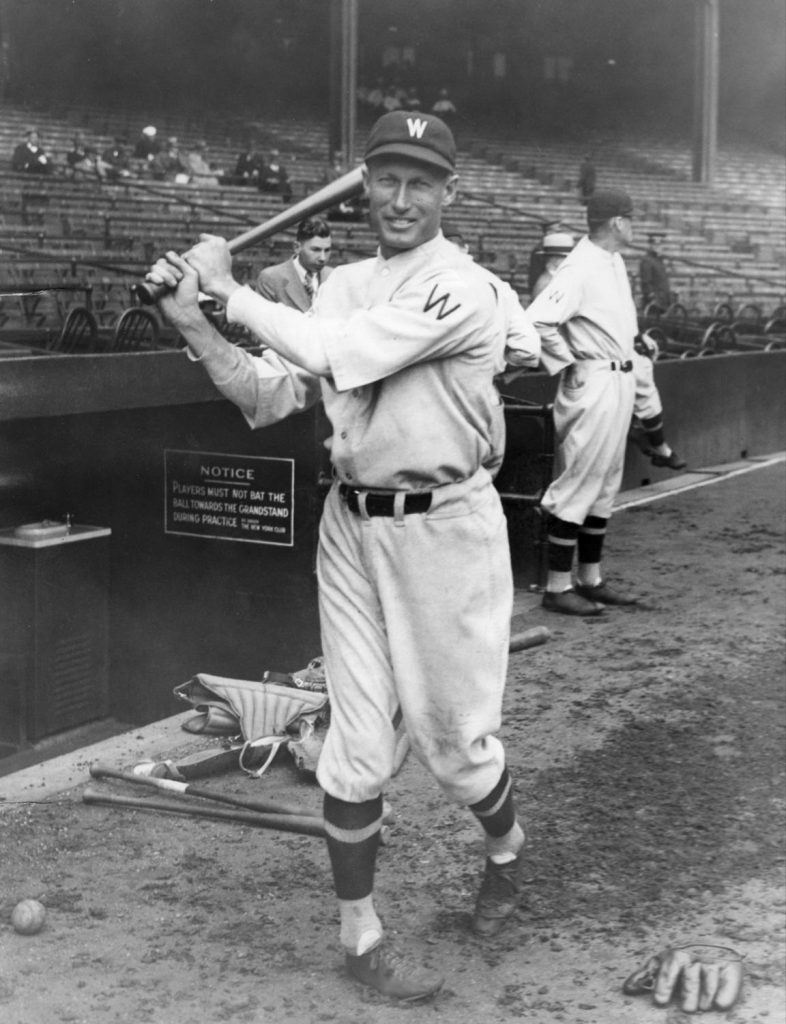

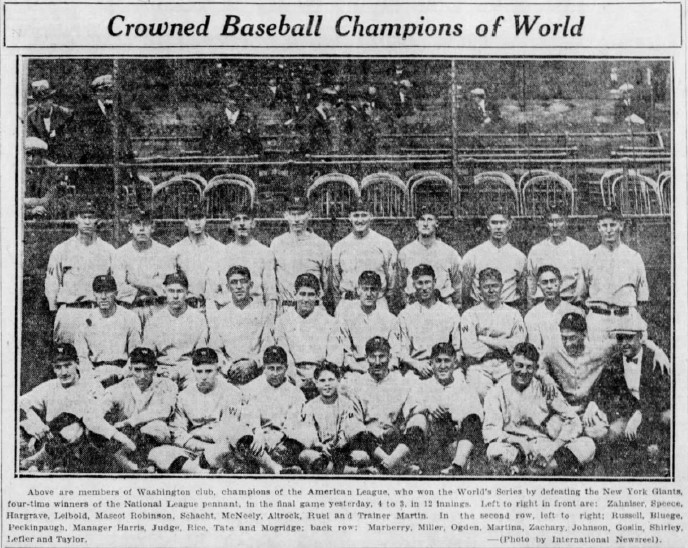

Washington’s ball club featured several future Hall of Famers during its championship runs in the 1920s and early 1930s. Most notable among them was pitching great Walter Johnson, but the roster also included lesser-known Hoosier outfielder Sam Rice, who was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1963. [3]

Rice spent nineteen of his twenty seasons (1915-1933) on the Senators. When he hung up his bat and glove for the last time with the Cleveland Indians following the 1934 season, he had amassed a career .322 batting average and 2,987 hits, just thirteen shy of baseball’s coveted 3,000-mark. To date, only 32 players in the history of the sport have achieved more hits than him. [4] And yet, despite his impressive statistics, Rice’s name remains largely unknown among even some of baseball’s biggest fans. Many would argue that it was due to his lack of power compared to some of the big hitters of the time (he only hit 34 homeruns during his entire career). More than likely, it’s because he was just short of the 3,000 club. Regardless, Rice was a mainstay for Washington and helped lead the capital city to three World Series appearances in the twentieth century. He was a quiet, but consistent force at the plate throughout his twenty years, a threat on the bases well into his thirties, and one of the greatest outfielders in the American League at the time.

Edgar Charles “Sam” Rice was born on a farm near the small town of Morocco, Indiana in 1890. His family moved between Newton County and Iroquois County, Illinois during his early years and Rice would eventually settle in Watseka, Illinois with his wife, Beulah Stam, and their two children. During the spring of 1912, he traveled to western Illinois to pitch for the Galesburg Pavers in the hopes of securing a spot on the minor league team’s regular roster. Unfortunately, those hopes were dashed almost immediately. On April 21, 1912, while away with the team, Rice received word that a tornado had torn through eastern Illinois and western Indiana, tragically killing his wife, children, parents, and two of his three sisters. [5] The tragedy clearly left its mark on him, but Rice rarely discussed it and few knew about this chapter of his life until decades later. With most of his family gone and no clear next step, he eventually enlisted in the Navy, serving aboard the USS New Hampshire. [6] During his service, the New Hamphire took part in the American intervention at Vera Cruz, Mexico.

Rice continued to play baseball with some of his fellow Navy men, and in the summer of 1914, while on furlough, he joined the Petersburg Goobers of the Virginia League. Impressed with his play, manager Heinie Busch and owner Dr. D.H. Leigh arranged for the purchase of his discharge from the Navy. He remained with the Goobers for the remainder of the season and for a good portion of the 1915 season, before Clark Griffith and the Washington Senators purchased his discharge in July 1915 at the age of 25. [7]

After a losing record during the 1923 season – and several previous disappointing seasons – few expected the Washington Senators to bounce back so well in 1924. With rookie manager Bucky Harris (who continued to play second base) at the helm, things finally fell into place for the Senators. After an average start, the team surged to the top of the rankings in mid-summer. By July 1, 1924, the Pittsburgh Daily Post suggested that they could be a “possible dark horse to win the flag,” noting:

Every American league fan is pulling for the Washington Senators to win the pennant, more out of sentiment than anything else. This team has been the underdog so long that the fans want them to win, not only the fans of the National capital, but in other American league cities. It would be a great thing for baseball if Washington could grab off a world’s series. [10]

The Senators battled the defending champion New York Yankees for control of the American League throughout August and September. During this remarkable stretch, Rice compiled a 31-game hitting streak, the longest in the Majors that season. [11] Within days of the streak ending, the Senators clinched the pennant to earn a spot in the World Series, where they would face the New York Giants.

On September 30th, a news article ran comparing the value of potential World Series players. In it, umpire Billy Evans described Rice as “one of the fastest men in the American League. Fine fielder, good baserunner, and dangerous batsman. . . A veteran who has played high-class consistent baseball throughout his career.” [12] Rice did not disappoint. He had two hits in Game 1 in which the Senators fell to the Giants 4-3 in 12 innings, and was one of the best hitters through the first three games of the series, going 5-for-11. [13] Though he struggled at the plate the remainder of the series, he made up for it in the field with several key defensive plays, including a homerun-robbing catch in Game 6 that helped save Washington’s season and force a Game 7. [14]

The series ended in similar fashion to how it started, with a spectacular 12-inning clash. The only difference was the victor. The Senators pushed the winning run across the plate in the bottom of the twelfth, defeating the Giants 4-3 to claim their first World Series championship.

The wildest, most frenzied demonstration that ever followed a world’s series victory came with the winning run. Most of the vast crowd of 35,000 which included President Coolidge, swept down on the field in a joy mad outburst of enthusiasm over the climax to Washington’s first pennant victory−her first World title. [15]

This week, America’s pastime has the opportunity to briefly unite the nation’s capital as it did in the 1920s and early 1930s, as the Washington Nationals try to return a World Series title to the city. As in 1924, Washington is considered the underdog, but this time to the favored Houston Astros. The Series is already spurring numerous articles recalling the 1924 season and more are sure to come. Sam Rice will be referenced, his name likely included among the list of strong outfielders and batters of that bygone team, but only today’s most devoted fans may recognize him. Nevertheless, Rice deserves the acclaim. As President Herbert Hoover wrote to him in July 1932: “You have given all of us who love baseball so much pleasure that you have rightly earned the honor of a ‘Sam Rice Day.’” [19] Rice earned the day and a whole lot more.

Edgar Charles “Sam” Rice historical marker notes.

“Sam Rice,” accessed Baseball Reference.

Footnotes:

[1] The Washington Homestead Grays of the Negro National League clinched three Colored World Series titles for the capital city in 1943, 1944, and 1948. They were the last professional baseball team based in Washington, D.C. to compete in a World Series.

[2] Washington’s Major League Baseball team was officially named the Washington Nationals from 1905-1956, but was more commonly known as the Washington Senators during this time. For more on this and on the various franchises that played in Washington, D.C. over the years, see “Washington Senators,” accessed Baseball Reference. The current Washington Nationals franchise was established as the Montreal Expos in 1969 and moved to Washington, D.C. in 2005.

[3] “Sam Rice,” National Baseball Hall of Fame. Rice was actually one of seven Indiana-born men on the two teams’ rosters. The others included Nehf and Grover Hartley of the Giants, and Nemo Leibold, Pinky Hargrave, Ralph Miller, and By Speece of the Senators.

[4] “Career Leaders & Records for Hits,” accessed Baseball Reference.

[5] “Seven Victims at Home of Charles Rice and Two at the Home of Charles Smart,” Newton County Enterprise, April 25, 1912, 1.

[6] “Edgar Rice,” U.S. World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, accessed AncestryLibrary.com.

[7] “Sam Rice Gets His Name in Big League Score for the First Time,” Washington Herald [Washington, District of Columbia], August 8, 1915, 9.

[8] “Rice will Report Ready for Season,” Washington Times, January 27, 1919, 17.

[9] “Sam Rice,” accessed Baseball Reference.

[10] “Fans Pulling for Senators to Win Flag,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, July 1, 1924, 14.

[11] “Hitting Streak of Sam Rice Stopped,” Boston Globe, September 27, 1924, 8.

[12] “How World Series Rivals Stack Up,” Times Herald [Olean, New York], September 30, 1924, 17.

[13] “Sam Rice Boss Series Hitter with Big 455,” News-Messenger [Fremont, Ohio], October 7, 1924, 6

[14] “Big Moments in World Series Games,” Pittsburgh Press, October 18, 1924, 11.

[15] “Washington Wins First World Championship,” Palladium-Item [Richmond, Indiana], October 10, 1924, 1.

[16] “Rice Secret Revealed: He Did Catch It,” Cumberland News [Maryland], October 15, 1974, 8.

[17] “Sam Rice to Join Cleveland Indians,” Sandusky Register [Ohio], February 14, 1934, 7.

[18] “Hall of Fame Voting Unfair, Says Hornsby,” Daily Independent Journal [San Rafael, California], January 21, 1958, 9.

[19] “Hoover Congratulates Rice, of Senators, for Record of 17 Seasons n Big Leagues,” Tampa Tribune, July 20, 1932, 8.

For more information, see the entry on Sam Rice by Stephen Able of the Society for American Baseball Research or Jeff Carroll, Sam Rice: A Biography of the Washington Senators Hall of Famer, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2008).