As John H. Holliday strolled through Indianapolis’s Hungarian Quarter, he observed windows caked with grime, street corners lined with rubbish, and the toothy grin of fences whose boards had been pried off and used for fuel. While reporting on the nearby “Kingan District,” Holliday watched plumes of smoke cling to the meat packing plant, for which the area was named. The philanthropist and businessman noted that in the district “boards take the place of window-panes, doors are without knobs and locks, large holes are in the floors, and the filthy walls are minus much of the plastering.”[1] Houses swollen with residents threatened outbreaks of typhoid fever and tuberculosis.

Those unfortunate enough to live in these conditions were primarily men from Romania, Serbia, Macedonia, and Hungary who hoped to provide a better life for family still living in the “Old World.”[2] Alarmed by what he witnessed, Holliday published his report “The Life of Our Foreign Population” around 1908. He hoped to raise awareness about the neighborhoods’ dilapidation, which, in his opinion, had been wrought by landlords’ rent gouging, the city’s failure to provide sanitation and plumbing, and immigrants’ inherent slovenliness (a common prejudice at the time). Holliday feared that disease and overcrowding in immigrant neighborhoods could spill into other Indianapolis communities.[3] Perhaps a bigger threat to contain was the immigrants’ susceptibility to political radicalism, given the squalor in which they had been reduced to living. Holliday wrote, “If permitted to live in the present manner, they will be bad citizens.”[4]

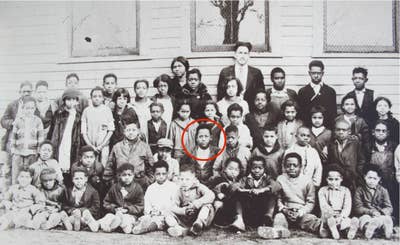

Motivated by a desire to both aid and control immigrants, a coalition of local businessmen-including Holliday-philanthropists, and city officials formed the Immigrant Aid Association in 1911.[5] Later that year, the association established the Foreign House on 617 West Pearl Street, which provided newcomers with social services like child care and communal baths, but also worked to assimilate and “Americanize” them. The Foreign House reflected the dual purposes of immigrant settlements in this period: what historian Ruth Hutchinson Crocker called “a mixture of protection and coercion.”

The first week of April 1908 was one of discord for northern Indiana. Hundreds of immigrant laborers stormed the Lake County Superior Court, “crying for bread” after the closing of Calumet Region mills. In Hammond, armed immigrants drilled together, causing police to fear the emergence of a riot. In neighboring Indiana Harbor, masses of desperate immigrants, many living in destitution, thronged the streets in search of employment. Blood spilled in Syracuse, when Hungarian laborers stabbed Sandusky Portland Cement Co. employee Bert Cripe. Apparently this was retribution for local employers’ refusal to hire Romanians, Hungarians, and “other laborers of the same class.” The stabbing set off a sequence of street fights between immigrants and locals, and resulted in the bombing of a hotel where laborers stayed. The Indianapolis News reported that the explosion “wrecked a portion of the building, shattered many windows, and not only terrified the occupants, but also the citizens of the town and country.”[6]

These alarming events made an impression on a nameless employee at Indianapolis’s Foreign House, who referenced the Indianapolis News article in the margin of a ledger three years after the foment.[7] The employee seemed acutely aware of the potential for unrest if the basic needs of Indianapolis’s estimated 20,000 immigrants went unmet.[8]

According to Crocker, by 1910, 80% of Indianapolis’s newcomers had originated from Romania, Serbia, and Macedonia. Many of those who had recently settled in the Hoosier capital had migrated from Detroit, Kentucky, and Chicago, in search of jobs.[9] Many Americans viewed such immigrants with derision, believing, as Holliday did, that they “‘differ greatly in enterprise and intelligence from the average American citizen. They possess little pride in their personal appearance and live in dirt and squalor.'”[10] The 1911 Dillingham Commission Reports, funded by Congress to justify restrictive immigration policies, was designed to validate these beliefs. Using various studies and eugenics reports, the commission “scientifically” concluded that Eastern and Southern Europeans were incapable of assimilating and thereby diluted American society.[11]

Reflecting the Report’s conclusions, a 1911 South Bend Tribune piece noted urgently, “A big portion of the immigrants are undesirable—very undesirable. . . . Mark this. If we don’t begin to really exclude undesirable immigration, the Anglo-Saxon in this Government will be submerged.” Its author continued that these “undesirables” would “soon become voters. Men who need votes see to that.”[12] The founders of Indianapolis’s Foreign House hoped to bring together various nationalities, as their isolation made them a “political and cultural menace.”[13]

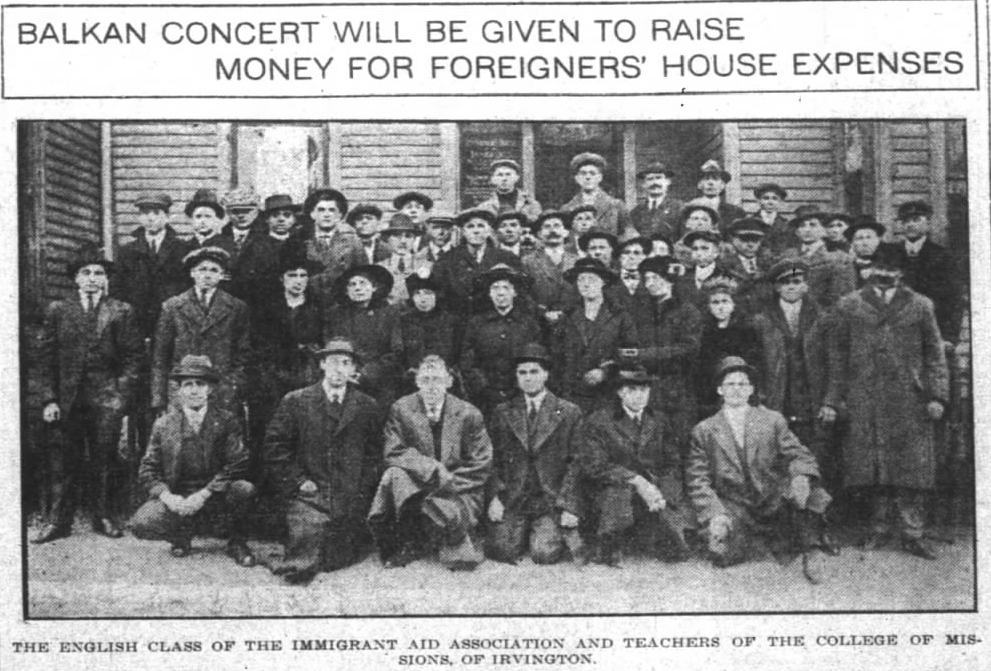

In fact, the House’s very foundations belied the American ideals of business philanthropy and civic volunteerism. Kingan & Co. essentially donated the settlement’s structure, the local community funded citizenship classes, and work was furnished partly through “personal subscriptions and the assistance of teachers who have volunteered their services.”[14] The settlement house would be modeled after YMCAs, offering baths, “reading and smoking rooms,” a health clinic, and night classes in which patrons could learn English.[15] Additionally, civics courses and an information bureau, where “all the dialects of the foreign population will be spoken,” helped immigrants understand American laws and navigate the citizenship process.

These classes were crucial, as ignorance about American customs resulted in many newcomers placing their money and trust in corner saloons, whose owners often mismanaged or pocketed the funds. Immigrant Aid Association officers hoped that “opportunities for grafting and theft among the gullible class of foreigners will be reduced when the settlement house is in working order.”[16] An understanding of the English language and the legal system could also help challenge the stereotype that immigrants were criminals because most offenses were committed due to their “ignorance of the law.”[17] Furthermore, the Star noted in 1914 that, according to those in charge, classes about American government “have given the students an increased earning capacity and have been of great benefit in fitting them for work in this country.”[18]

Questions about their intellectual aptitude persisted, as noted by the Indianapolis Star‘s 1915 observation of immigrants in night school: “It is an interesting sight to watch the swarthy men bending over their books and making awkward attempts to follow the pronunciation of their teachers.” Despite such evaluations, it is clear than many immigrants were grateful for the quality of education afforded in America. As relayed by an interpreter and printed pejoratively in the Indianapolis Star, a young Macedonian man who had recently arrived to Indianapolis “says he thankful most for the education he is gettin’ in America. He wants to bring father and mother here to free country.”[19]

While the Foreign House introduced men to American cultural and political norms through these courses, immigrant women were indoctrinated through home visits by Foreign House staff.[20] Ellen Hanes, resident secretary of the organization, made 2,714 trips to women’s homes in 1913, “teaching the care of children and teaching domestic economy as practiced by American housewives.”[21] Historian Ruth Hutchinson Crocker contended that such services:

were the medium for teaching ‘correct’ ideas about a variety of subjects, from the meaning of citizenship to the best way to cook potatoes; thus they always involved the abandonment by immigrant women of traditional ways of doing things.[22]

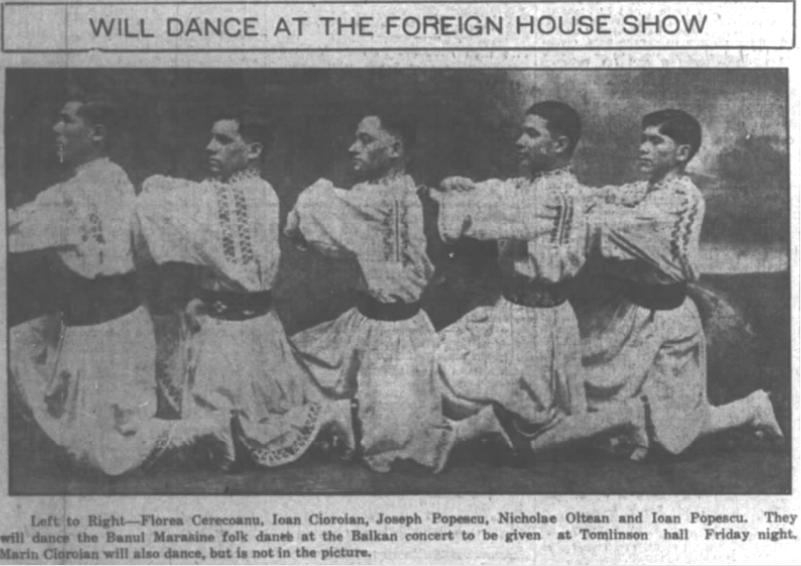

In addition to providing instruction about American customs, the House offered a space for fellowship and recreation. Likely feeling isolated in their new country, immigrants could socialize there and enjoy musical programs, as well as literary clubs with fellow newcomers. They could don costumes from their homeland, often “rich and heavy with gold and embroidery,” and perform folk dances and native music. Conversely, much of the entertainment centered around American patriotism, like a program for George Washington’s birthday, in which men dressed like the first president and women the first lady. The Indianapolis Star noted, “Probably at no place in Indianapolis are holidays celebrated more earnestly.”[23] Crocker contended that this blended programming “showed the settlement in the dual role of Americanizer and preserver of immigrant culture.”[24]

Recreational opportunities also lowered the possibility that immigrants would become a societal “liability.” One man who dropped by the house said, “‘We used play poker and go saloon and dance when we come Indianapolis. . . but now we read home books in our library, read English, do athletes, play music and do like Americans.'”[25]

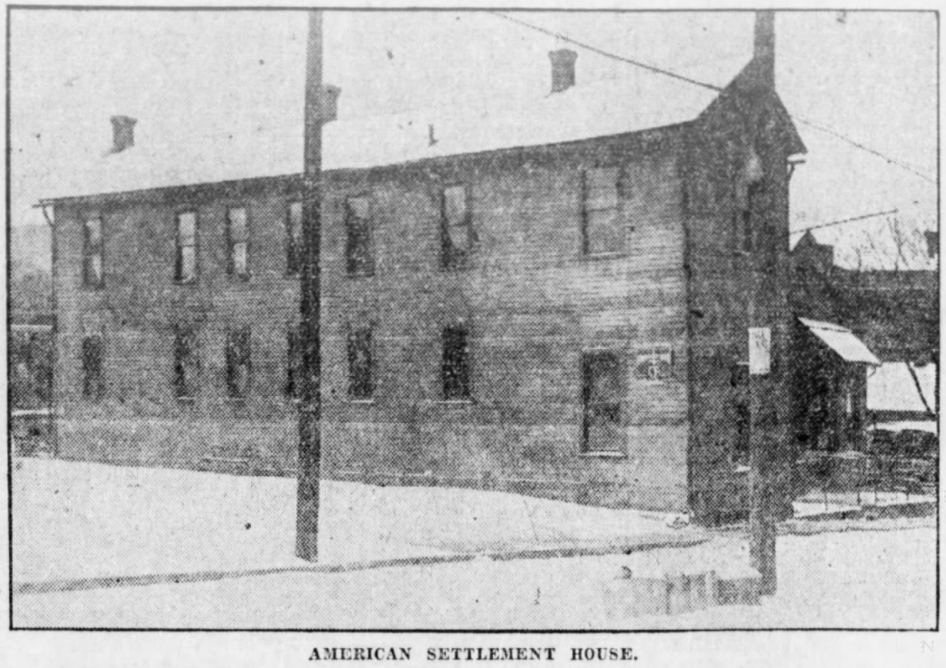

America’s entry into World War I in 1917 intensified suspicion of immigrants and spurred questions about their loyalty. This hostility impacted foreign institutions like Indianapolis’s German-language paper, the Täglicher Telegraph und Tribüne, which, despite trying to present balanced war coverage, ceased publication by 1918. In the years following World War I, the Foreign House was “practically abandoned,” perhaps another victim of xenophobia surfacing from the war’s wake. The emerging nationalist impulse likely accounted for the organization’s name change.[26] The Foreign House became the American Settlement House in 1923, when the organization merged with the Cosmopolitan Mission and moved to 511 Maryland Street (where the Indiana Convention Center now sits).[27]

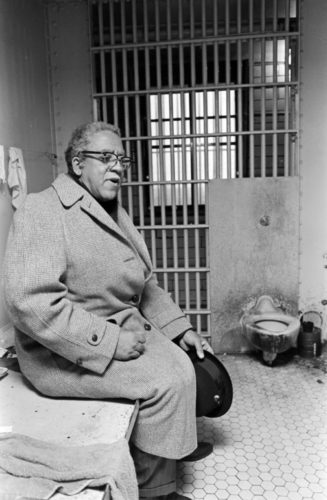

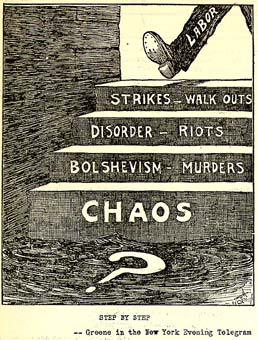

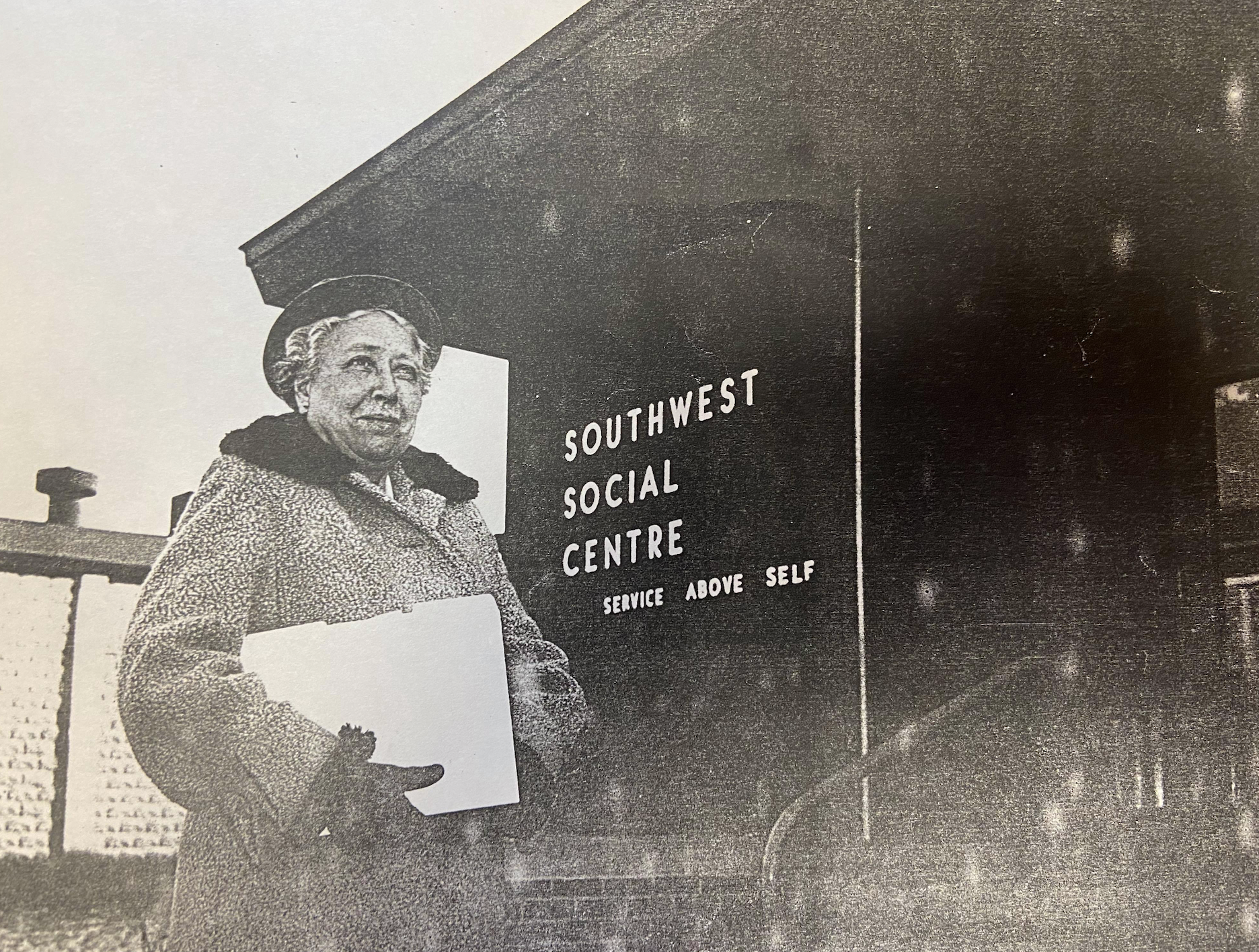

Post-war labor strikes, anarchists’ bombing of American leaders, and fears that Eastern European immigrants would replicate the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution increased suspicion of and reduced support for immigrants. It also helped inspire the 1924 Immigration Act, which set an annual immigrant quota of 150,000 and drastically curtailed admittance of people from “undesirable” countries.[28] A sense of isolation must have intensified for Indianapolis’s immigrants, now deprived of the settlement house’s resources and contending with renewed nativism. That is until Mary Rigg, a young, idealistic social worker was put in command of the American Settlement House in 1923. While conducting research for her thesis about the settlement, Rigg developed an affinity and deep empathy for its visitors. She began to envision a robust image of their future. With the assistance of the House, immigrant neighborhoods blossomed with colorful flowerbeds, giggling children shimmied up gleaming jungle gyms, and neighbors shared the bounties of a communal garden.

The goal would not simply be to help newcomers find employment, obtain citizenship papers, or avoid disease, but to experience, as Rigg stated, “true neighborliness,” where they “could play the game of daily living together in peace and harmony.” Rigg would be chief architect of this idyllic vision, in which immigrants could taste the fruits of capitalism, while embracing their native customs, language, and dress. After all, she believed that living “in a country in which we have the privilege of climbing higher” applied to its immigrants and that it was the settlement’s responsibility to help them ascend its steps. [29]

* Read Part II to learn how “Mother” Mary helped engineer a vibrant urban community and hear from those who thrived in it.

Sources:

*All newspapers were accessed via Newspapers.com.

[1] Sarah Wagner, “From Settlement House to Slum Clearance: Social Reform in an Immigrant Neighborhood,” 1-4 in 1911-2001: Mary Rigg Neighborhood Center, 90 Years of Service, given to the author by Mary Rigg Neighborhood Center staff.

[2] Ruth Hutchinson Crocker, Social Work and Social Order: The Settlement Movement in Two Industrial Cities, 1889-1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 47.

[3] Wagner, 2-6.

[4] Crocker, 49.

[5] “Foreign Quarters in City to be Improved,” Indianapolis News, July 29, 1911, 16.

[6] “Foreigners Clamoring for Something to Eat,” Indianapolis News, April 8, 1908, 8.; “Riot at Syracuse Ends without Loss of Life,” Indianapolis News, April 8, 1908, 8.

[7] Mary Rigg Neighborhood Center Records, 1911-1979, L130, Indiana State Library.

[8] Foreign population estimate is from “Library Orders Foreign Works,” Indianapolis Star, April 19, 1914, 51.

[9] Crocker, 14, 47.

[10] Wagner, 5-6.

[11] “Dillingham Commission Reports (1911),” accessed Immigrationhistory.org.

[12] “The Latin Will Overcome the Anglo-Saxon in this Country in a Few Year,” South Bend Tribune, January 5, 1911, 3.

[13] Crocker, 48.

[14] Wagner, 6.; Indianapolis Star, February 21, 1915, 3.; “Library Orders Foreign Works,” Indianapolis Star, April 19, 1914, 51.; Quotation from “Members of Civic League Criticise [sic] School Board in Not Giving Assistance,” Indianapolis Star, January 7, 1913, 9.

[15] “Foreign Quarters in City to be Improved,” Indianapolis News, July 29, 1911, 16.

[16] “Advise Foreigners to Avoid Saloons,” Indianapolis Star, October 7, 1911, 7.; “Foreign Quarters in City to be Improved,” Indianapolis News, July 29, 1911, 16.; “Members of Civic League Criticise [sic] School Board in Not Giving Assistance,” Indianapolis Star, January 7, 1913, 9.

[17] “Advise Foreigners to Avoid Saloons,” Indianapolis Star, October 7, 1911, 7.

[18] “Scope of Night Schools for Foreigners Broadened,” Indianapolis Star, August 13, 1914, 16.

[19] “Thankful to be Free,” Indianapolis Star, December 1, 1911, 8.; Indianapolis Star, February 21, 1915, 3.

[20] “Advise Foreigners to Avoid Saloons,” Indianapolis Star, October 7, 1911, 7.

[21] Indianapolis Star, September 13, 1914, 38.

[22] Crocker, 59.

[23] Indianapolis Star, February 21, 1915, 3.; “School Popular with Foreigners,” Indianapolis Star, September 13, 1914, 38.

[24] Crocker, 58.

[25] Indianapolis Star, September 13, 1914, 38.; “School Popular with Foreigners,” Indianapolis Star, September 13, 1914, 38.

[26] Crocker, 60.; German Newspapers’ Demise historical marker, courtesy of the Indiana Historical Bureau.; “Xenophobia: Closing the Door,” The Pluralism Project, Harvard University, accessed pluralism.org.

[27] Crocker, 60-61.; Wagner, 7-8.

[28] “Sacco & Vanzetti: The Red Scare of 1919-1920,” accessed Mass.gov.; “The Immigration Act of 1924,” Historical Highlights, History, Art & Archives: United States House of Representatives, accessed history.house.gov.; David E. Hamilton, “The Red Scare and Civil Liberties,” accessed Bill of Rights Institute.

[29] Crocker, 60-65.; Master’s thesis, Mary Rigg, A.B., “A Survey of the Foreigners in the American Settlement District of Indianapolis,” (Indiana University, 1925), Mary Rigg Neighborhood Center Records.; Bertha Scott, “Mary Rigg Busier Since ‘Retirement,'” Indianapolis News, November 3, 1961, 22.; Laura A. Smith, “Garden and Home First Wish of New Americans,” Indianapolis Star, July 6, 1924, 36.; Letter, Mary Rigg, Executive Director, Southwest Social Centre to Mr. Joseph Bright, President, City Council, May 15, 1953, Mary Rigg Neighborhood Center Records.