Esther Griffin White was a woman before her time—outspoken, rebellious, and willing to stake her reputation on the things that she believed in during an era when women were considered second-class citizens. Her Quaker upbringing imparted the importance of racial and gender equality, causes that she ultimately championed throughout her life. Her staunch political activism and dedication to gender equality throughout her life are, arguably, what she is most known for today. However, she also used her power, privilege, and platform as a white, middle-class, female journalist to speak out against racial injustice. Here, as we examine White’s writing, we clearly see someone trying to make sense of her own ingrained racism while at the same time standing up and speaking out against it.

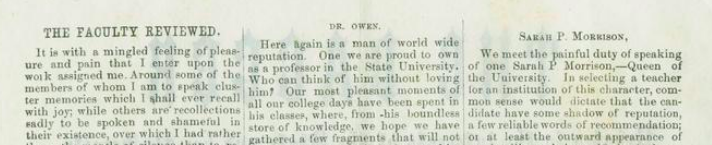

Born in 1869 in Richmond, Indiana, White was a journalist, political activist, suffragist, and life-long Indiana resident. She began her writing career for the Richmond Palladium as an arts and culture critic and published her own paper (though infrequently) called The Little Paper, which she owned and operated out of her home at 110 South 9th Street. From the 1890s to 1944, she freelanced for many Richmond papers, often transferring from publication to publication as editors worried that her blunt and adversarial writing style could offend readers—likely a concern born partially out of sexism.

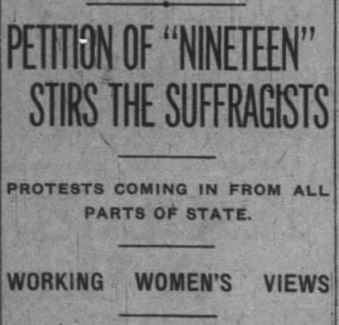

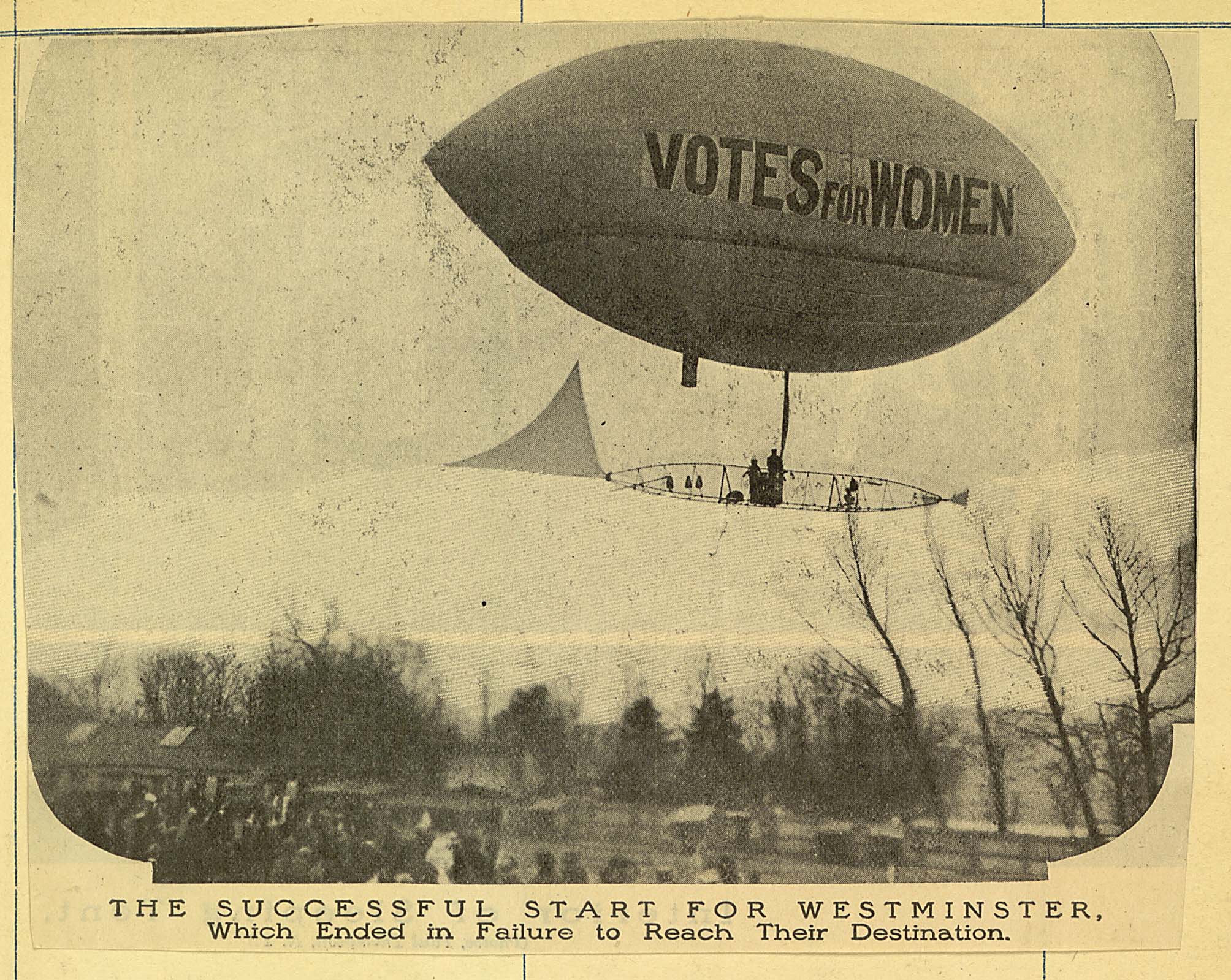

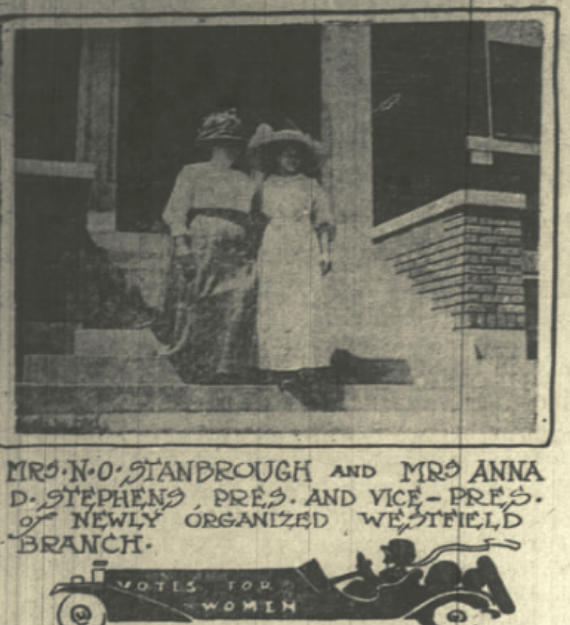

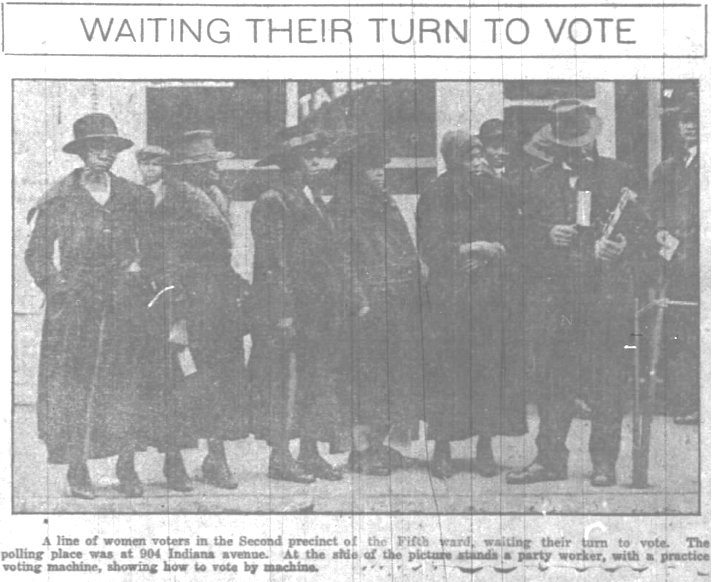

White joined the Indiana Woman’s Franchise League in the early 1900s and was elected chairman of the Publicity Committee in 1916. While in the League, she began actively working towards the cause she wrote so much about; for example, she organized a suffrage street rally for several suffrage speakers in June 1916 in Richmond. This event was heralded as “one of the largest street meetings ever held in Richmond and the first suffrage meeting of its character held in eastern Indiana.”[1]

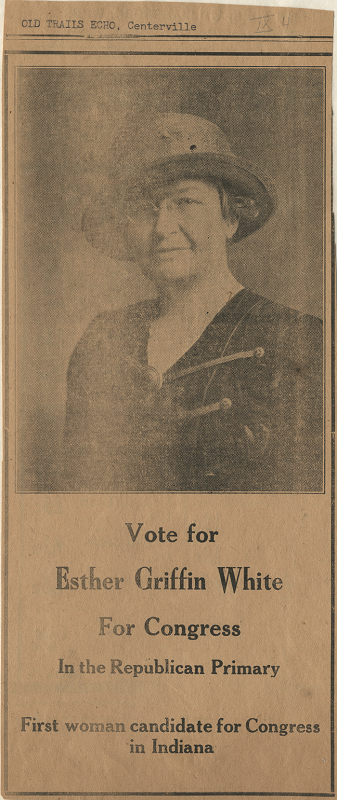

White was also a politician, running for mayor of Richmond in 1921, 1925, and again in 1938. She also ran for a Republican congressional seat in 1926, making her the first Indiana woman to seek U.S. congressional office. White ran for a seat in the U.S. Congress again in 1928, but to no avail. According to historian George T. Blakey, White was the first Hoosier woman to have her name on an official election ballot, before women even had the right to vote, when she ran for a delegate’s seat at the 1920 Republican State Convention.[2] Though White never held elected office, her ambition sent a strong message—that women could and should be recognized as political actors and that, as far as White was concerned, would no longer accept anything less.

While she is probably best known for her work to advance women’s rights, she was also a proponent of racial equality and used her journalistic platform to speak about racial issues in the town of Richmond, Indiana throughout the first half of the 1900s. An active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), White’s opinions on and support of African Americans garnered plenty of scorn and judgment in her small, rural town—especially because she was a single white woman.[3] Never one to care about others’ opinions of her, White used her talent, privilege, and position as a white female journalist to speak out against racial discrimination. Through her editorials and opinion pieces in both The Richmond Palladium and her self-published newspaper, The Little Paper, between 1910 and 1920, White condemned white supremacy and racial discrimination. Though she often wrote antiracist sentiment, on occasion her choice of words and arguments were in themselves racist—as she often touted common assimilationist and segregationist points of view. Through her published articles, we see the ways in which White grappled with her own ingrained and unconscious racism as she worked to be (what we call today) an antiracist in 20th-Century Richmond, Indiana.

Professor of history and founding director of the Antiracist Research and Policy Center at American University, Dr. Ibram X. Kendi, explains the relationship between antiracist, assimilationist, and segregationist beliefs:

the history of the racialized world is a three-way fight between assimilationists, segregationists, and antiracists. Antiracists ideas are based in the truth that racial groups are equals in all the ways that they are different, assimilationist ideas are rooted in the notion that certain racial groups are culturally or behaviorally superior, and segregationist ideas spring from a belief in genetic racial distinction and fixed hierarchy.[4]

We find representations of each of these ideals, often within the same article, throughout White’s analysis of race. Though we understand that racial inferiority or superiority does not exist—all races are the same and race itself is a construct—we too understand that many people across time, and still today, have used pieces of assimilationist and segregationist ideas in their defense of equal treatment of the races. These racist ideas are so deeply ingrained in our societies that, although plenty of racist people have used them intentionally, plenty of others, like White, who believed in equality between the races, also sometimes unknowingly peddled racist beliefs.[5]

White was, as were some of her well-known contemporaries, engaging in the work to become an antiracist and to communicate antiracist ideas, while also at times touting assimilationist and segregationist ideas, which were prevalent views in terms of race in nineteenth and twentieth century America, and even today. However, highlighting White’s racist tendencies is not to discredit any of the antiracist beliefs she so clearly held—it is simply to be completely transparent about the reality of this type of work and the people engaged in it. She was not a perfect antiracist, but she was trying—she was standing up for what she believed in and, through her journalism, speaking on ideas of racial equality when it was not only unpopular to do so, especially for a woman, but potentially dangerous.

The last years of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth century in America saw a rise in violence against African Americans by white supremacists looking to quell any power or rights the group received in the years after the Civil War.[6] The violence emerged, most horrifically, in the form of mob violence and lynchings, many of which were not hidden events done in the dark of the night, but rather public spectacles that often doubled as picnics for families and town folk.[7] Though the majority of lynchings occurred in the South, this barbaric act transcended regional lines and can be found nationwide. Mobs throughout the Hoosier state alone murdered at least sixty-six people between 1858 and 1930, eighteen of whom were African Americans.[8] Black men were not the only targets of lynchings, as Native American, Hispanic, Asian, white people, and women and children too were lynched across the United States.

There were no recorded lynchings in Richmond, perhaps because of its large Quaker community and the anti-slavery beliefs they held.[9] The closest recorded lynching to Richmond occurred in Blountsville, about thirty miles northwest of the city, in February of 1890.[10] However, the possibility of such violence constantly lingered in the minds of Black Americans. These conditions at the turn of the twentieth century prompted Esther Griffin White, as a white, female journalist to speak out against the unjust treatment of African Americans.

In one of her most notable articles pertaining to race, written in her self-published The Little Paper, White expressed disdain for the depiction of African Americans in the blockbuster hit of the early twentieth century, The Birth of a Nation. This controversial film released on February 8, 1915 by D.W. Griffith claimed to represent the Civil War and Reconstruction in America. However, it depicted the Ku Klux Klan as the valiant saviors of the ravaged, post-war South by freed, barbaric Black people. The film was a commercial hit and helped to rekindle the once regional Ku Klux Klan founded in 1865. It depicted freed Black Americans as “uncouth, intellectually inferior and predators of white women.”[11] The Birth of a Nation prompted protests by the NAACP, but they had little impact as the films’ popularity was so wide. In fact, President Woodrow Wilson showed it at the White House, heralding it as “writing history with lightning.”[12]

While she found the musical score and the general cinematography of the film noteworthy, Esther Griffin White did not share the same fervor over the film as President Wilson and so many other white Americans. In her newspaper review of the film, titled “’The Birth of a Nation’ Insidious Appeal to Race Prejudice, An Insult to Negro Citizens,” White writes that “colored people are justified, without any shadow of doubt, in their protest against the second part of ‘The Birth of a Nation.’” She continued, “the play is merely a dramatization of a novel by a well-known fire-eating Southern writer, who has done more to rake up old scores, to intensify class hatred, to accentuate race antagonism by his lurid pictures of conditions long since passed away than any other one medium in the United States.”[13] Here, we see White expressing contempt for the bestial, racist depiction of Black Americans in the film. She also adds:

The second part of ‘The Birth of a Nation,’ if it were looked upon as picture commentary on a phase of the country’s history, might be interesting. But the presentation is not made for this reason. On the other hand neither is it made for the glorification of a lost cause. Its raison d’etre is not philanthropic nor moral nor historic. But commercial…[it] is a business proposition. To make money for its producers.[14]

White seems to clarify here that she does not believe the film to be historically accurate or looking to start a conversation about the country’s past, but rather inflammatory and insulting to African American citizens: “the Negro citizen of this country was sacrificed to make a moving picture holiday, so to speak. The glaringness of the sop thrown to them by the scenes at the end . . . is laughable if it were not sardonic.”[15] This review of The Birth of the Nation was certainly not the first, nor the last, public condemnation White would make regarding the treatment of African American citizens in the twentieth century.

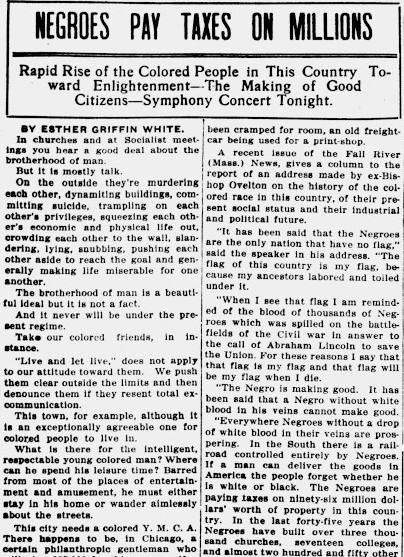

In one of her earliest political articles from December 1911 in the Richmond Palladium, White writes about the idea of brotherhood and humanity among all people, and the exclusion of African Americans from those ideals. In her article “Negroes Pay Taxes on Millions,” White writes, “take our colored friends, in instance. ‘Live and let live,’ does not apply to our [white Americans’] attitude toward them. We push them clear outside of the limits and then denounce them if they resent total excommunication.”[16] While it seems here that White is arguing for the indiscriminatory inclusion of African Americans within American society and against segregation, further on in the article she begins arguing for more Black organizations to be formed in Richmond for Black residents, like a “colored” Y.M.C.A. for the “well behaved, educated and ambitious young colored men in this city.”[17] Rather than arguing for inclusion and accessibility, it seems White instead argued for the racist separate but equal doctrine we see come to a head in the 1890s with the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) case in response to African American’s push for equal treatment and opportunity under the law.

She continued, “they [Black Americans] are just as much a part of the social, economic and political life of the community as their paler-hued brothers and unless given some consideration will develop into a complicated and puzzling problem. . . . They are citizens of this country just as are the whites.”[18] This perfectly illustrates White’s struggle with the idea of dueling consciousness as it relates to assimilationist and antiracist ideas. At the end of the article, White argues that “there is no use retiring into the fastness of race prejudice and lumping all of the colored people together. There are as many grades and distinctions as there are among the white people.” This comment, as well as many of the other antiracist sentiments White expressed throughout this article, demonstrate her ability to understand and express the antiracist notion that all races are the same—it is individual distinctions that make humans different—distinctions that have nothing to do with the color of their skin. This article, as a whole, demonstrates her own dueling consciousness as a white woman trying to pursue an antiracist mindset and advocating for antiracist policies while also struggling to unlearn deeply rooted racist ideals in the early twentieth century.

The very next month, in January of 1912, White was much more explicit about her views of racism. In her article, while arguing generally for universal gender and racial equality as it pertains to voting and citizenship, White laments:

Why, in instance, “call names.” Why say “niggers,” “dagoes,” “shenies.” Why arrogate yourself a certain superiority because you have a white skin. Who made the “earth and the fullness thereof”? How do you know who got here first? Who are you, anyway? In a few years you will be turned over to the worms who make no distinction between black or white, man or woman, good or bad, educated or uneducated, yellow or red, brown or copper. Neither God nor the worms care what your color may be, your race or your previous condition of servitude. There is nothing so immoral as thinking you are better than anyone else.[19]

In this article, perhaps her most antiracist, White does not allude to any racist or assimilationist ideals. As can be noted in the excerpt above, she completely disdains any ideology that espouses the belief that one’s skin color makes them any different.

Just a few months after the above article, White wrote another piece for the Richmond Palladium titled “It Is True You Can’t Always Tell.” In this article, White builds on her antiracist views and highlights an experience she had a few weeks prior while attending a concert in Richmond. She noted how wonderful the musical act performed by a group of male musicians was and that “they were, indeed, one of the best ‘attractions’ the vaudeville theatre has ever had.” [20] She continued that many of the spectators thought them Italian, as they sang many of their songs in Italian, or perhaps Spanish, because they were dressed as troubadours, but that they were in fact African American. This, White argued, proved that “race prejudice is frequently only a matter of thinking” and that “people were delighted with [the musicians]—not because they were Italians or Spaniards, white Americans or of the Negro race, but because they were superior musicians.”[21]

Here, White is arguing that race prejudice and racism are not logical —they are both only a matter of warped thinking. The musicians were not loved and celebrated because of their prescribed race, but simply because they were talented. White continued, “it is one of life’s famed tragedies that these people should have to masquerade, after a fashion, in order to have their talents appreciated for what they really were.”[22]

Looking back at Esther Griffin White’s life reveals many things about her as a person, which can generally be boiled down to one sentiment: she was unapologetically her own person and used her power, privilege, and platform as a white, middle-class, female journalist to speak out against injustices. Through White’s articles, we clearly see someone trying to process her own ingrained racism while at the same time speaking out against it. That is essentially what happens when engaging in antiracist work. White did not always say or do the right things when it came to her antiracism work, but one can trust in her intentions and hope that she learned from her mistakes. Ultimately, her fearless condemnation of injustice in early-twentieth century Richmond should inspire us all, perhaps now more than ever, to stand up and speak out for what is right, even if it is unpopular.

Notes:

[1] “Suffrage Street Talks Draw Large Audience, Women State Their Purpose,” Richmond Palladium, June 27, 1916, 1, 11, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[2] George T. Blakey, “Esther Griffin White: An Awakener of Hoosier Potential,” Indiana Magazine of History 86, no. 3 (September 1990): 294-299, accessed scholarworks.iu.edu.

[3] Blakey, 286.

[4] Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (New York: Penguin Random House, 2018), 31.

[5] So common was the dance between antiracist and assimilationist ideas for people that well-known Black author and activist W.E.B. Du Bois wrestled with them. In The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois’ 1903 essay, he expressed the dueling consciousness that demonstrates the fight between assimilationist and antiracist ideas, specifically for Black folk: “One never feels his twoness…an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”[5] Although Du Bois, as a Black man, had disproportionately different experiences than White did as a white woman, we see a similar push and pull between assimilationist and antiracist ideas in his defense of African American’s racial equality that we do in White’s writings.

[6] Michael J. Pfeiffer, Lynching Beyond Dixie: American Mob Violence Outside of the South (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 1.

[7] Pfeiffer, 4. The more secretive, hidden lynchings would occur in the latter half of the twentieth century, often carried out by secretive groups like the KKK and often shrouded as “hate crimes” rather than what they were. It was middle-class southerners’ embarrassment at the newfound spotlight anti-lynching activists like Ida B. Wells were putting on the barbaric practice that drove it underground in the mid-twentieth century. In some areas, like the Midwest and West, public lynchings would continue into the mid-twentieth century.

[8] Pfeiffer, 9.

[9] “Early Black Settlements by County,” Research Materials, Indiana Historical Society, accessed indianahistory.org.

[10] Ibid., 1.

[11] Alexis Clark, “How ‘The Birth of a Nation’ Revived the Ku Klux Klan,” History Channel, accessed history.com.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Esther Griffin White, “‘The Birth of a Nation’ Insidious Appeal to Race Prejudice, An Insult to Negro Citizens,” The Little Paper, February 19, 1920, 1, accessed Earlham.edu.

[14] Ibid., 1.

[15] Ibid., 1.

[16] Esther Griffin White, “Negroes Pay Taxes on Millions,” Richmond Palladium, December 6, 1911, 7, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[17] Ibid., 7.

[18] Ibid., 7.

[19] Esther Griffin White, “It Don’t Take Long When You’re a King,” Richmond Palladium, January 24, 1912, 6, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[20] Esther Griffin White, “It Is True You Can’t Always Tell,” Richmond Palladium, February 21, 1912, 6, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[21] Ibid., 6.

[22] Ibid., 6.