We are all familiar with the stereotype of corrupt and power-hungry politicians who do whatever it takes to win and get their party into office. This stereotype has been around for centuries and in fact still influences public perception about candidates’ motivations for running for elected office. This stereotype emerged because there have been corrupt politicians in the past, and the State of Indiana is no exception. For example, in the 1920s, the Indianapolis Times exposed the influence of the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana politics via bribes to several high-ranking politicians in the state, including Governor Ed Jackson.[1] As recently as this year, two former members of the Indiana General Assembly (IGA) were sentenced to federal prison for breaking election finance law.[2] Therefore, it is not unreasonable for Hoosiers and their fellow Americans to be a bit skeptical regarding the intentions of politicians. Given that citizens are the ones electing politicians, we have a responsibility to hold them accountable and look critically at their actions, since it affects our lives.

But in fairness, however, state legislators have historically come into office via a variety of different means, from different backgrounds, and with different motivations. In the course of my work as a historian for the Indiana Legislative Oral History Initiative (ILOHI), I have found there are many elected officials who essentially stumbled into politics. This has been one of the intriguing aspects of conducting interviews for ILOHI. Take for instance, the former Republican Calvin Didier, who served in the House of Representatives in 1961. Prior to serving in the Assembly, Didier was a minister in La Porte. Members of his congregation began to recruit him to run for office, claiming they did not feel well-represented by the legislature and believed he would be a good candidate. When recounting this story, Didier remembered his puzzled reaction, saying “‘No, I can’t do that.’ I mean, you know a minister doesn’t run very often, but they pushed hard enough, in terms of wanting a candidate and apparently, I had some popularity in that small community. So, you know I said, ‘well okay nothing to lose’ and I agreed.” Subsequently, Didier would go on to win his election, showing how communities can play a major role in determining who runs for office. During his legislative service, he was known for his ability to work with both parties and get along with everyone. He also worked to prevent churches from taking advantage of their tax exemptions, feeling that even as a minister it was unethical.

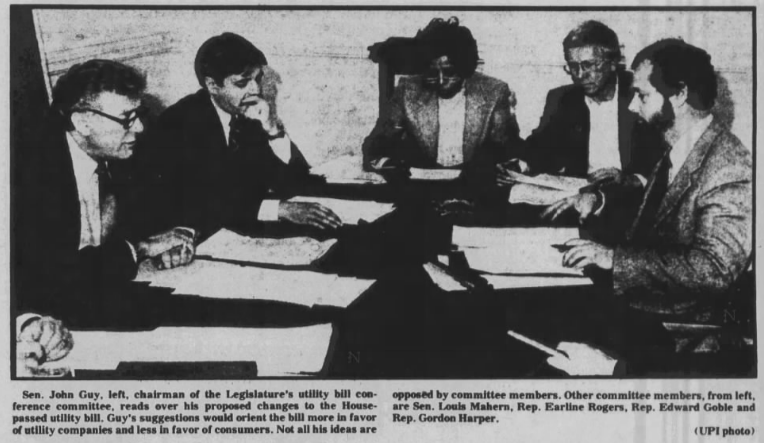

However, Didier was not the only legislator encouraged to run by their community. This was also the case for former Democratic legislator Earline Rogers. Rogers served in the Indiana House of Representatives from 1983 to 1990 and the Indiana Senate from 1990 to 2016. Despite Rogers having no prior interest in politics, she accepted the Gary Teachers Union suggestion that she run for office. Once elected to the Assembly, Rogers proved to be very influential in education reform, such as helping casino legislation get passed to increase government revenue to help fund education.

Alternatively, some legislators were recruited by political parties in their communities but not through the stereotypically “nefarious” ways. In one humorous instance, a former representative was chosen to run for office completely out of the blue when an outgoing representative in the IGA needed a replacement. This was the case for former Democratic Representative Jesse Villalpando, who served in the House from 1983 to 2000. At the time of his recruitment, Villalpando was a student and magician at Indiana University-Bloomington when one of his roommates informed him a man had called about a job offer. As it turned out, this man was Representative Peter Katic, who had met Villalpando only once, after one of Villalpando’s magic shows. However, before he returned Katic’s call, he called his mother. And to Villalpando’s total surprise, his mother informed him that he was running for office. As Villalpando recounts, “I called my mom first and my mom is excitable. She said, ‘I just heard it on WJOB Radio, you’re a candidate for State Representative. . . . I said ‘What did you say?’ . . . I have no idea what she is talking about.” Ultimately, despite being shocked by all of this, Villalpando would run for office, and this former representative’s decision to volunteer Villalpando as his replacement, would lead to Villalpando serving almost twenty years in the House. He was influential in helping create the CLEO bill, which would provide legal educational opportunities for underrepresented students preparing to go to law school.

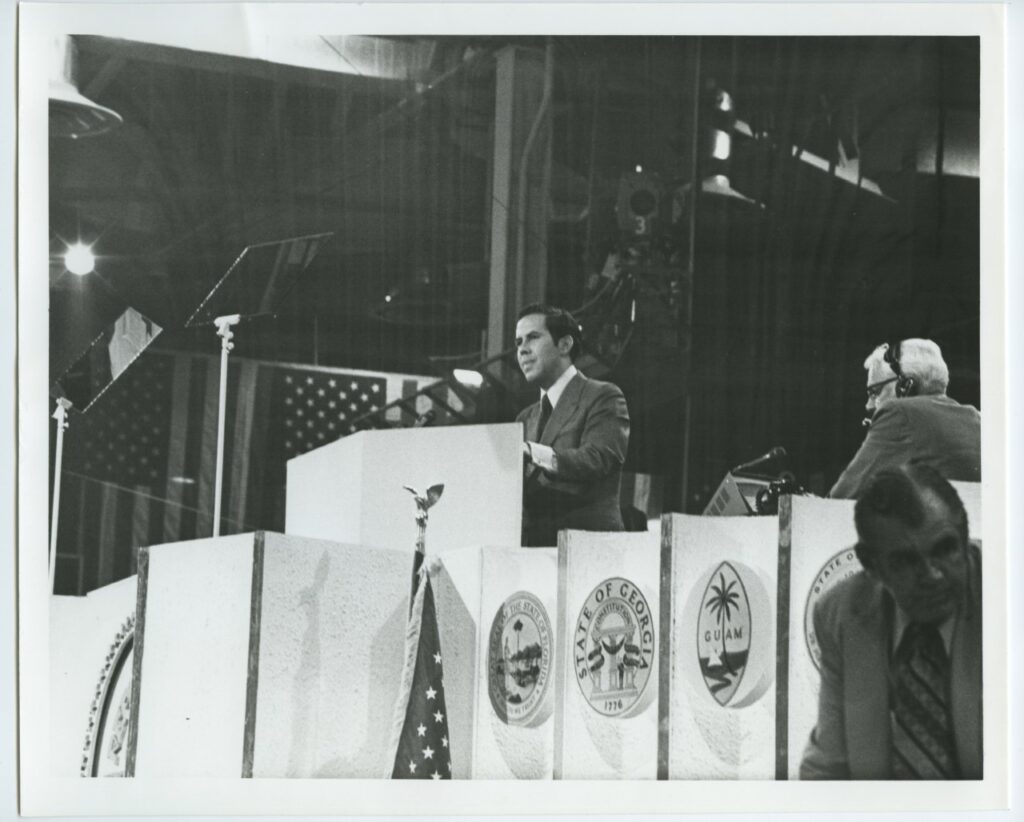

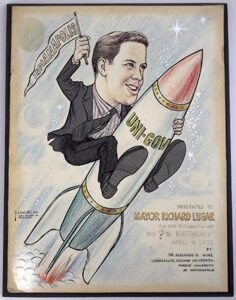

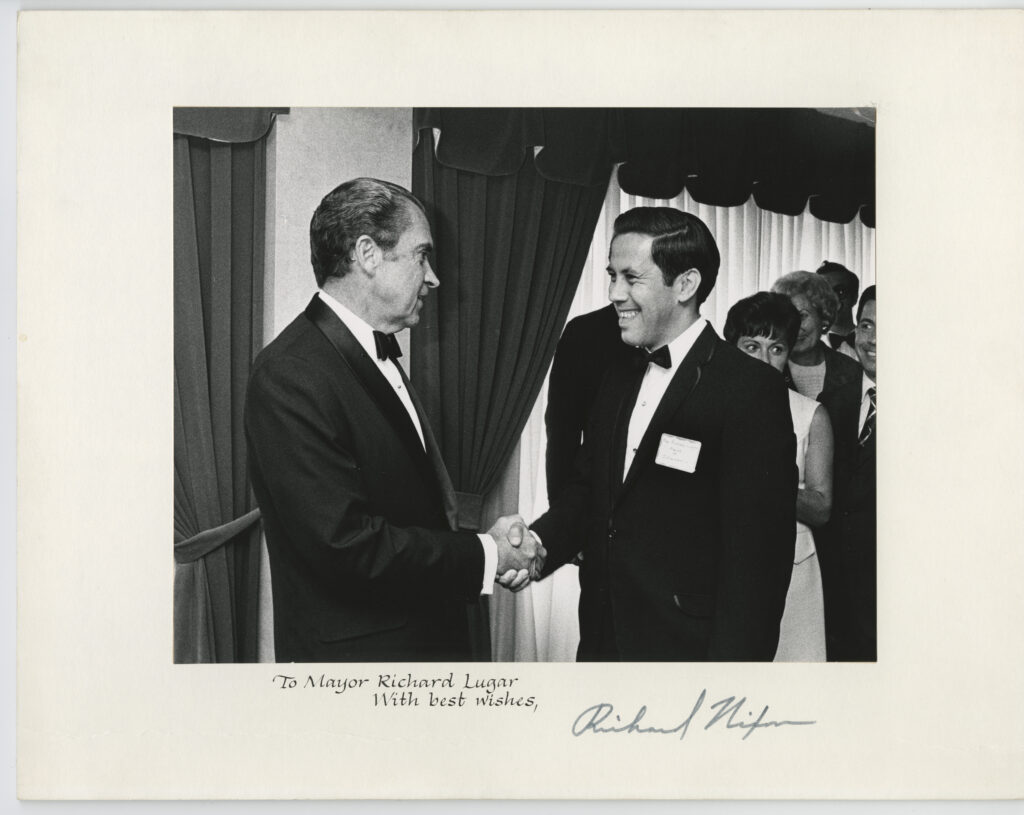

Lastly, like the recruitment of Jesse Villalpando, State Senator Stephen Ferguson, was also talked into running for office by local members of the Republican Party in his community. Like Villalpando, Ferguson had no interest in running for the Indiana General Assembly and even refused to run when first asked. It was only later that Ferguson was talked into it and then went on to win his election, serving in the Indiana Senate from 1967 to 1974. He played an important role in the creation of Unigov, which had a transformative impact on the city of Indianapolis.

There are many reasons why someone runs for office, as highlighted by the dozens of ILOHI interviews conducted over the past 4 years. The legislative office comes with power and influence certainly, but the ILOHI interviews demonstrate that usually is not the driving factor for why someone runs for the Indiana General Assembly. Many legislators simply get involved because they were convinced that they could help their communities. And despite the long-standing stereotype, financial greed is not likely a motivating factor, as the pay is low in the Indiana General Assembly, since it is a part-time body. As pointed out by the Indy Star in 2021, legislators’ salaries were under $30,000.[3] Based on ILOHI interviews, most former legislators testify to genuinely wanting to help their communities. Whether they succeeded or not is up for you to determine.

Notes:

[1] Jordan Fischer, “The Dragon & the Lady: The Murder that Brought Down the Ku Klux Klan,” WRTV, August 22, 2017, accessed wrtv.com.

[2] Press Release, “Former Indiana State Senator and an Indianapolis Casino Executive Sentenced to Federal Prison for Criminal Election Finance Schemes,” U.S. Attorney’s Office, Southern District of Indiana, August 17, 2022, accessed justice.gov.

[3] Tony Cook, “Analysis: Part-time Legislators Earn About $65.6K/yr.” Indianapolis Star, August 15, 2021, accessed Indystar.com.