This post draws on more extensive research completed by the author, Cory Balkenbusch, and Jennifer Mara DeSilva. For a full article on this research, see “Toleration of Sex Work in East Central Indiana, 1880-1900” in the upcoming December 2023 edition of the Indiana Magazine of History.

In April of 1894, Muncie policemen Ball, Cole, and Coffey assisted Chief Miller on a raid of a “Palace o’ Pleasure.” When the officers arrived, they discovered “six very well-known young gentlemen,” who were “being entertained” by four women.[1] The Muncie Daily Herald revealed that the young men and their paid female company swiftly scraped together enough money and valuables to give bond, with one man even giving an officer a valuable diamond stud that was given to him by his mother.[2] The resort, located on Vine Street, was owned by a woman who went by the name of Rosenthal. It quickly became notorious for its illicit activities, with another raid occurring in May of 1894, in which four girls and seven men were arrested and charged with “associating.”[3]

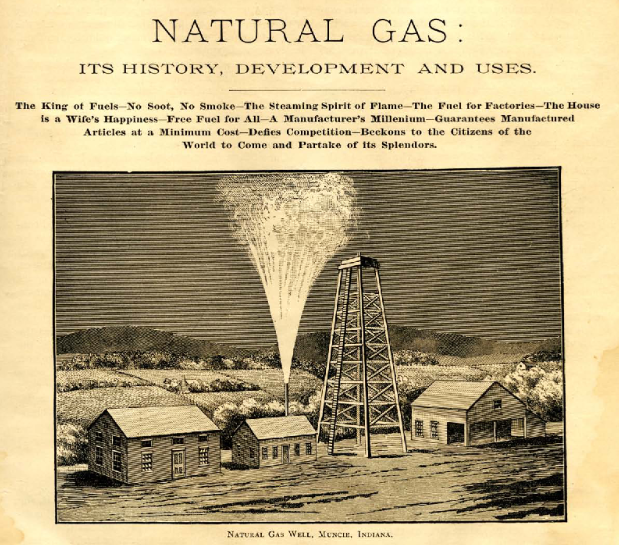

Muncie newspaper readers during this era would not find the reports regarding Rosenthal’s “Palace O’ Pleasure” terribly shocking. During the Gas Boom, sex work was increasingly becoming a part of Muncie’s cultural and social landscape. By the end of the nineteenth century, a substantial reservoir of natural gas was discovered in East Central Indiana, prompting surrounding cities like Muncie, Anderson, and Kokomo to rush to discover their own supply.[4] Despite commonly-held assumptions about American small towns and cities, they were not isolated from the influence of their distant metropolitan cousins. In the two decades before the twentieth century, new railway, telegraph, and telephone connections linked small towns and cities more intimately with the urban centers.

As historians Frank Felsenstein and James Connolly have argued, Muncie, Indiana reflected this rural-urban network. Their research has contrasted Robert and Helen Lynds’ depiction of a sleepy agricultural center recently industrialized in their landmark 1929 study Middletown.[5] However, historians have chiefly focused on the city’s cultural achievements and technological progress brought upon by the Gas Boom, ignoring a large facet of the economy: the exchange of sexual services. Indeed, between 1880 to 1900, the Gas Boom and subsequent industrialization spearheaded the growth of Muncie’s sexual exchange network. This played an integral role within its growing economy.

The Gas Boom, Working Class Men, & The Rise of Sex Work

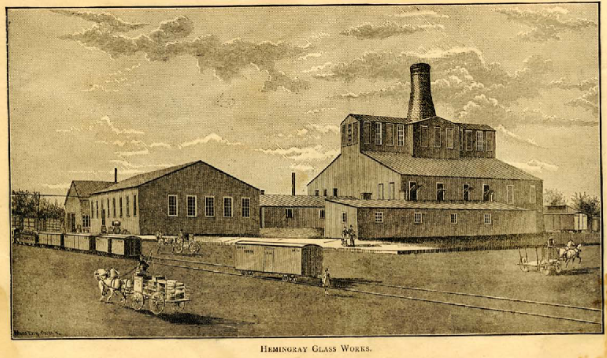

By the spring of 1887, the Muncie Natural Gas Company laid gas mains across most sections of town and was piping inexpensive gas to individual households and businesses.[6] Within that same year, gas had replaced the need for coal, leaving the city free from soot and ash. Forward-thinking businessmen like James Boyce, a member of Muncie’s board of trade, energetically pursued business ventures both for personal gain and to bring new factories to town. Boyce persuaded the Over window glass plant, the Hemingray bottle plant, and the famed Ball Brothers Company to build in Muncie. The working population doubled from 5,500 in 1886 to 11,345 in 1890, and Muncie was quickly becoming the largest city in the Indiana Gas Belt.[7] In turn, the city’s industrial and demographic explosion after 1886 entirely transformed Muncie’s neighborhoods and entertainment districts. By the end of the century, almost seven times the number of original saloons operated throughout the city and nearly double the number of boarding houses and hotels lined Walnut Street.[8]

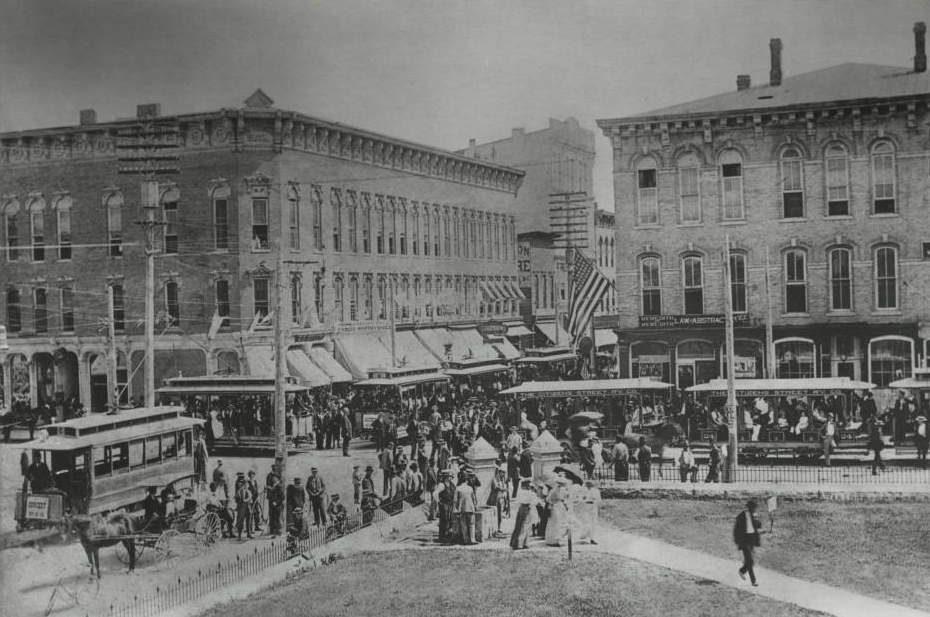

As Muncie’s working-class male population grew, saloons became spaces for men to socialize and relieve the stresses of factory work. Relief could be found in conversation, intoxication, sport or musical entertainment, and female company. Sex work often accompanied the development of urban, commercial, and transportation infrastructure.[9] As the north-south artery running straight through the city, Walnut Street connected Muncie’s downtown district with the railway depot. It continued into a new residential area that grew beyond the railway tracks to support workers at the surrounding factories. The Southside neighborhood’s location, at the intersections of the C.C.C. & St. Louis Railroad Lines and the L.E. & W. Railroad Lines, coupled with its proximity to the commercial district, made it a hotbed for sex work. The steady flow of newcomers and addition of boarding houses and saloons around the train depots provided potential clients and encounter sites. As early as 1890, Muncie’s newspapers reported Southside sex workers and their clients being arrested and fined.

Establishing Networks & the Commercialization of a Sex Work

While the Southside was largely cut off from Muncie’s wealthier commercial district by railway lines, the saloons that lined Walnut Street to the north continued to the south. The 1886 Sanborn map identifies a barber, grocer, jeweler, and three saloons that occupied a block between 1st and 2nd Streets. Sanborn maps show that east of Walnut Street, the Southside neighborhood was made up of houses, bringing businesses like the Muncie Lumber Company, the Artificial Gas Works, the Muncie Foundry & Machine Shop, and the Anheuser-Busch Beer Depot. Although it is hard to determine if these dwellings functioned as boarding houses, there was one known boarding house listed on the 1896 Sanborn map.

The boarding house was located off Walnut Street and might have offered factory men a livable space close to their place of employment. This boarding house occupied the same building as a saloon, with two additional saloons and one restaurant nearby, underlining the proximity to possible prostitution. Widows frequently ran boardinghouses to replace their lost husband’s income. However, the commercialization of women’s labor degraded her role as “keeper of the house.”[10] This highlights the effects of the Victorian middle-class ideals, as paid labor was viewed as a masculine activity. Moreover, contemporaries viewed boarding houses with suspicion because they often sheltered single women and men in proximity, which undermined the idealized purity of middle-class homes. The possibility of sexual activity between unmarried men and women cast suspicion on boarding houses, and aligned them with brothels, which sometimes masqueraded as “female boarding houses” on Sanborn fire insurance maps.[11]

To find direct evidence of sex work, one needed only to follow South Walnut Street into Muncie’s Southside. Much like Chicago’s sex district, known as the Levee, Muncie’s Southside brothels operated openly, and some women used boardinghouses to meet clients.[12] Unlike middle-class neighborhoods in the northern half of the city that were cut off from factory development and train depots, the Southside sheltered working-class men and families that moved to Muncie as new factories opened. From the late 1880s, women engaging in the sex trade gravitated towards the neighborhood. The number of established brothels, sex workers employed in this area, and the prevalence of their arrests reported in the newspapers evinced this movement.

Not long after he acquired it from Henry Coppersmith, John Mullenix’s saloon earned a reputation for being an “awful, wicked, sinful joint,” and one of the “toughest holes in Indiana.” Mullenix arranged for Minnie White, also known as “Gas Well Minnie,” to use the saloon as a base for exchanging sexual services.[13] The saloon’s location positioned both Mullenix and White to make a profit from travelers, as well as local factory workers. The saloon, located about a block south of the railroad line, was surrounded by four large manufacturing plants, ensuring patronage. Additionally, about twelve dwellings on the saloon’s block might have served as boarding houses for the men working close by. Elsewhere, tavern keepers relied on sex workers to attract customers, while women often relied on tavern keepers for a space to engage in their sexual services, much like Mullenix and White did in Muncie.[14]

However, women engaging in sex work did not limit themselves to working-class neighborhoods and saloons. Indeed, Muncie’s entertainment and business district offered some women the chance to profit from wealthier clientele. The High Street Theater reflected this trend noted by other historians, as concert halls and theaters became popular new venues for sex and entertainment by the beginning of the twentieth century.[15] Located directly across the street from Delaware County’s courthouse, the theater’s wine rooms were open all hours of the day. Initially, the newspapers portrayed wine rooms as a sign of the city’s metropolitan character, but by 1900 they were a source of communal outrage.[16]

Venues like the High Street Theater catered to a wealthier clientele than the Southside working-class. Clients paid an entrance fee, after which they climbed a stairwell that led to small apartments overlooking the theater’s main auditorium. These semi-private rooms were essentially pine boxes with lace curtains to conceal the activity from the audience down below. In these wine rooms, scantily clad women encouraged clients to buy drinks and other services. These costs required a clientele with sufficient disposable income, something most of Muncie’s factory workers could not claim.[17]

An undercover police officer noted that “Age and color [were] no disqualifications” to visit the theater, making it clear that vice activities attracted far more wealthier men than young factory workers. [18] While single factory workers might have money to spend, Muncie’s older and wealthier men also visited the theater. In 1895, Rhoda Jones arrived at the High Street Theater Restaurant and attempted to climb the staircase to find her husband, George Jones. Although the attendant claimed that the wine-rooms were closed at 11pm, Rhoda was insistent that her husband was present. She argued that each night he walked north from their grocery store on South Walnut Street to visit the wine-room women.[19] Although Rhoda’s arrival appeared in the next day’s newspaper, her husband’s departure was more covert. For men like George, the theater also had alleyway access to several city streets, allowing all clients to make easy escapes and discreet entrances.

Property Ownership & Economic Profitability

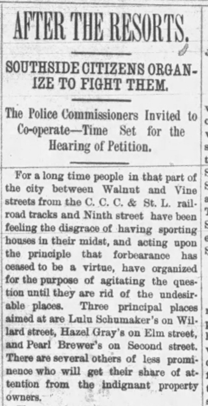

Social reform efforts in the late 1890s underlined the development of a new vice district. By early 1896, Southside citizens had mobilized a reform campaign. On January 26, 1896, the Muncie Daily Times described an attempt to close organized brothels. Between Walnut and Vine Streets, stretching to the C.C.C. and St. Louis Railroad tracks, down towards Ninth Street, the Muncie Daily Times reported that citizens held a “feeling of disgrace” living among houses of “ill-repute.”[20] The tension and notoriety surrounding prostitution is apparent from the newspaper’s willingness to identify prominent brothel owners. Between 1887 and 1896, it had become clear to Muncie’s Southside that an extensive prostitution network had developed. Newspaper accounts sensationalized and corroborated citizens’ concerns. “Soiled Doves” and “Women of ill-repute,” such as Emma Bryant, Hazel Gray, and Kate Phinney, provided Muncie’s newspapers with frequent material for reports of their sexual escapades and commerce.

The effort to close brothels within the Southside neighborhood also revealed the prominent role that sex work played within Muncie’s booming economy. Numerous newspaper articles, like that published by The Muncie Daily Times on January 26, 1896, highlighted the extensive network of female-owned brothels and the way they generated city profits through county court fines. Despite the continuous raids these women faced, city officials never forced their brothels to shut down. Their services, and the fines that these raids produced, were an integral part of the Muncie’s urban economy.

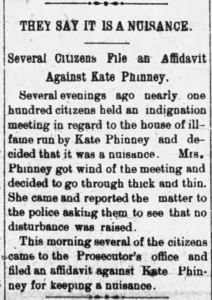

For example, in 1891, The Muncie Daily Times reported on a brothel raid that occurred on Third Street, outing five individual women working at the location, including the proprietress, Minnie Dwyer. Those arrested and put before the judge pleaded guilty to prostitution, paying fines of $16.85.[21] Dwyer was not the only woman running a brothel, however. In 1892, the Muncie Morning News reported that nearly “one hundred citizens” gathered to discuss Kate Phinney’s “house of ill-fame,” and ultimately decided it was a nuisance.[22] The Southside’s saloons, boarding houses, and brothels became woven into this area’s economy of leisure, transiency, and commercial sex.

Emma Bryant was one of the most prominent sex workers and brothel owners in the area, appearing six times in the Delaware County Court Records for her involvement in vice activity, including prostitution, witness to prostitution, and witness to violent crimes.[23] However, the newspapers revealed that Bryant often paid hefty fines rather than serving jail time. As early as 1894, Bryant’s “bawdy house” was raided by police, but remained opened.[24] Her brothel on Council Street, known as Gaiety Commons, appeared later in 1895 in The Muncie Morning News when Bryant along with seven young men and two young women were arrested on charges related to the illegal monetary exchange of sexual services.[25] That same year, Bryant was arrested for selling alcohol without a license, but she paid $200 (equivalent to $6,117.81 today) and was released.[26] Despite the continuous raids these women faced, city officials never forced their brothels to shut down. As historian Ruth Rosen has described, sex workers’ services, and the fines that these raids produced, were an integral part of the urban economy in many American cities.[27] Muncie sex workers produced considerable revenue for the city through the fines they paid.

Prostitution on the Southside bolstered the city’s real estate economy. Muncie sex workers actively engaged in purchasing and selling property and securing mortgages. Kate Phinney and Hazel Gray weathered frequent raids, but always found a new location for their businesses. Phinney faced a plethora of fines and charges related to prostitution but remained an integral part of the vice district, moving her brothel from South Plum Street into Shedtown (current-day Avondale neighborhood). Hazel Gray, appearing as early as 1894 in the newspapers, moved her brothel from Second Street to Third Street. Like Phinney, Gray also faced numerous prostitution charges until she left town in 1897. Phinney’s and Gray’s ability to move around the Southside suggest that there was a tolerance of the profession among city officials.

The Southside citizens were seemingly successful in their efforts to close the local brothels. The Muncie Morning News reported that by March 1896, brothels run by Emma Bryant, Kate Phinney, and others had been shut down.[28] However, many of these “businesswomen of ill-repute” did not leave Muncie. According to the Muncie City Directory, Emma Bryant was still living on South Willard Street in 1901. Muncie’s 1897 city directory listed Hazel Gray as living at 138 Kinney Street. These directories reveal that, although their brothels were initially shuttered, these women moved freely about Muncie, redefining the vice district limits.

By 1900, 347 manufacturing establishments operated within the city and Muncie boasted a population of 20,942. However, the industrial optimism brought on by the discovery of natural gas would not last long. By the beginning of the 20th century, gas pressure dropped to nearly 100 pounds and many large factories could no longer obtain the natural gas they had so heavily utilized during the previous decade. This caused many factories to find other means of production or shut down. Unlike smaller cities in Eastern Indiana, like Fairmount and Eaton, the growth of Muncie’s railway lines provided convenient access to coal, raw materials, and markets for finished manufactured products, which maintained its industrial prominence after the gas ran out. The movement of factories closer to the railway lines prompted Muncie to grow in all directions, with new industrial areas materializing at both the north and south ends of the city.

Muncie’s sex work industry continued to follow the Walnut Street corridor, then flowing out towards industrial areas. As in other cities, the industry maintained a connection to the city’s entertainment district throughout the Gilded Age, providing clients with easy access to vice. However, during the Progressive Era, sex work was forced underground. As social reformers sought to solves issues created by Gilded Age industrialization, Gas Boom Muncie offers historians a chance to understand how Gilded Age vices took hold of smaller-scale urban spaces, creating a new narrative of how these areas reflect larger city trends when regarding the link between sex work and the local economy.

Notes:

[1] “A Large Catch,” The Muncie Daily Herald, April 5, 1894, accessed Newspapers.com.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Vine Street Joint,” The Muncie Morning News, June 1, 1894, accessed Newspapers.com.

[4] James Glass, “The Gas Boom in Central Indiana,” Indiana Magazine of History 96, no. 4 (2000): 315.

[5] Frank Felsenstein and James J. Connolly, What Middletown Read: Print Culture in an American Small City (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015), p. 17-20; Robert S. Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd, Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1929), p. 5-6.

[6] Remarkably, in 1892 the state reported that 2,500 square miles of natural gas could be located across Central Indiana making it the largest known gas field—larger than the Pennsylvania and Ohio fields combined. Glass, “The Gas Boom in Central Indiana,” 315.

[7] Glass, “The Gas Boom in Central Indiana,” 318.

[8] Charles Emerson, 1893-1894 Emerson’s Muncie Directory (Muncie: Carlon & Hollenbeck, 1893), accessed Ball State University Digital Media Repository.

[9] Katie M. Hemphill, “Selling Sex and Intimacy in the City: The Changing Business of Prostitution in Nineteenth-Century Baltimore,” in Capitalism by Gaslight: Illuminating the Economy of Nineteenth-Century America, eds. Brian P. Luskey and Wendy A. Woloson (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), p. 169.

[10] Wendy Gamber, The Boardinghouse in the Nineteenth Century (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2007), p. 60.

[11] Kristi L. Palmer, “Fire Insurance Maps: Introduction and Glimpses into America’s Glass Manufacturing History,” The News Journal 20, no. 4 (2013): 4; Gamber, The Boardinghouse in the Nineteenth Century, p. 102-103.

[12] Cynthia M. Blair, I’ve Got to Make My Livin’: Black Women’s Sex Work in Turn-of-the-Century Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), p. 27.

[13] “For Min White and Bomb Shell for The Quart Shop: The Police and Residents of South Walnut Street Very Sore on John Mullenix’s Wicked Joint,” The Muncie Morning News, March 12, 1893, accessed Newspapers.com.

[14] Hemphill, “Selling Sex and Intimacy in the City,” p. 172-173.

[15] Timothy J. Gilfoyle, City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution, and the Commercialization of Sex, 1790-1920 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1994), p. 224; Ruth Rosen, The Lost Sisterhood: Prostitution in America, 1900 -1918 (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1982), p. 83-84.

[16] “A Wine Room,” The Daily Muncie Herald, November 15, 1892, accessed Newspapers.com.

[17] “Muncie’s Den of Iniquity,” The Star Press, January 28, 1900, accessed Newspapers.com.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “After Hubby,” The Muncie Morning News, April 5, 1895, accessed Newspapers.com.

[20] “After the Resorts: Southside Citizens Organize to Fight Them,” The Muncie Daily Times, January 26, 1896, accessed Newspapers.com.

[21] “A Third Street Joint Raided and Ten Victims Gathered,” The Muncie Daily Times, October 26, 1891, accessed Newspapers.com.

[22] Phinney had been charged with keeping a house of ill-fame as early as 1890, and then again in 1895 and 1898; Delaware County Circuit Criminal Court, Cause #2547 (1890), 3031 (1895), 3480 (1898); “They Say It Is A Nuisance: Several Citizens File and Affidavit Against Kate Phinney,” Muncie Morning News, May 19, 1892, accessed Newspapers.com.

[23] Delaware County Circuit Criminal Court, Cause #3546 (1897), 3494 (1898), 3737 (1900), 8409 (1927).

[24] “Bawdy Houses Raided: The Inmates of Three Bagino’s [sic] in Courts To-Day,” The Muncie Daily Times, January 1, 1894, accessed Newspapers.com.

[25] “It Comes High: But the Boys Will Stray Into The Path That Leads to Headquarters,” Muncie Morning News, March 19, 1895, accessed Newspapers.com.

[26] “In The Hands of U.S. Officials,” The Muncie Daily Times, March 2, 1895, accessed Newspapers.com.

[27] Rosen, The Lost Sisterhood, p. 74-75.

[28] “After Questionable Houses: There Will Be None Left in Muncie After March 10,” Muncie Morning News, February 20, 1896, accessed Newspapers.com.