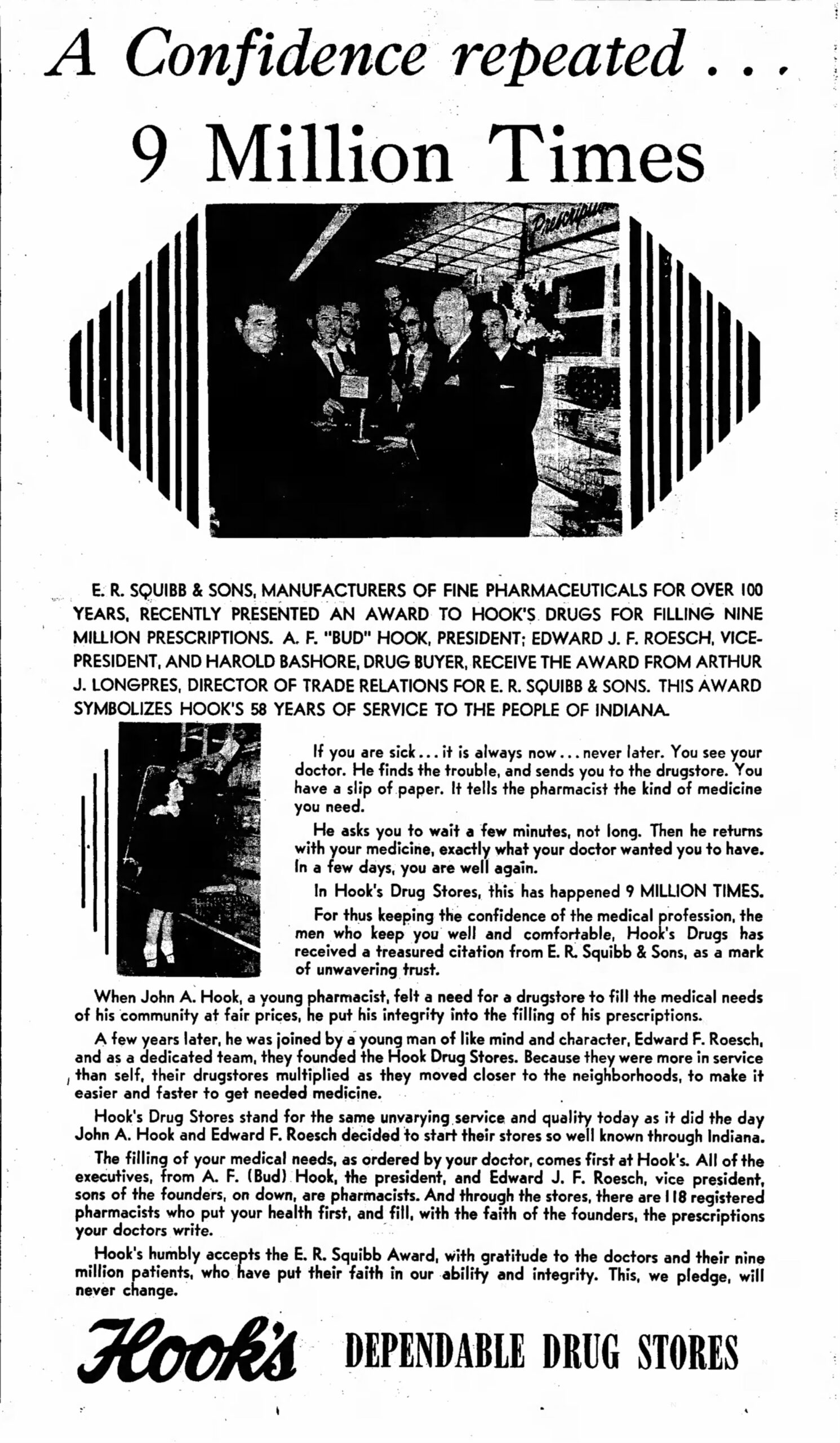

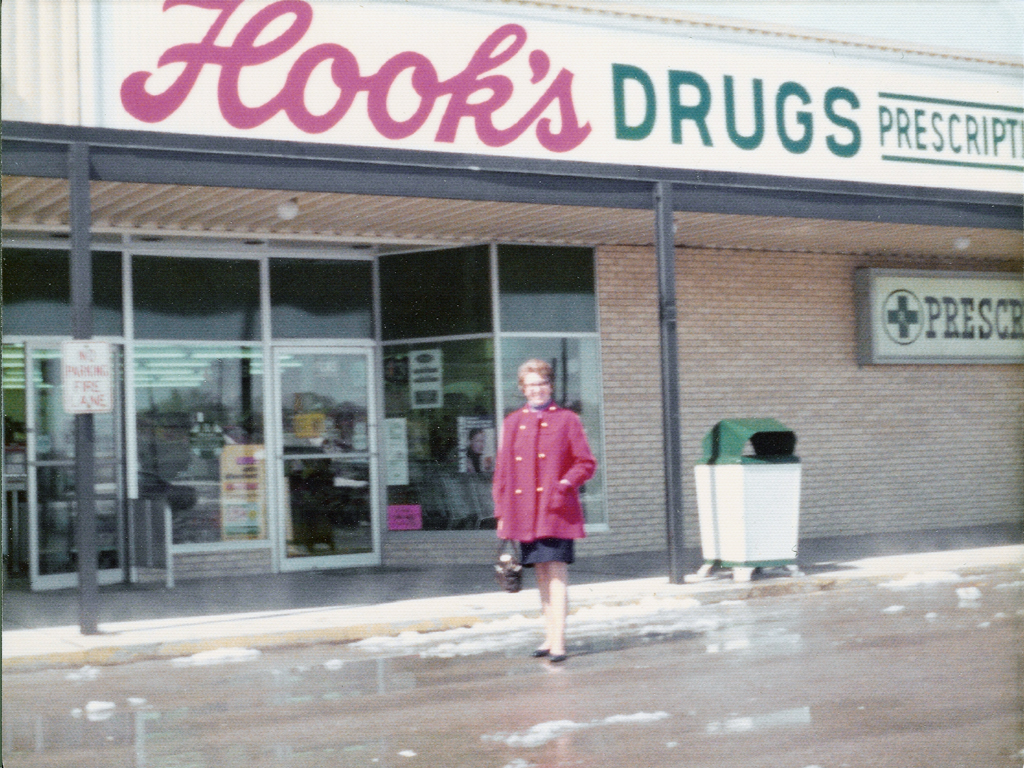

This splashy 1958 advertisement printed in the pages of the Terre Haute Tribune speaks to public health issues that remain relevant today, as shown by philanthropic entrepreneur Mark Cuban’s new Cost Plus Drugs company. When John A Hook established his first drug store in 1900, he “felt a need for a drugstore to fill the medical needs of his community at fair prices, [and] he put his integrity into the filling of his prescriptions.” Over five decades later, as John Hook’s small chain of stores expanded into a statewide brand, the company’s commitment to “filling the medical needs of the community” never wavered. In addition to offering affordable health care, the company advanced racial equality and worked to prevent drug abuse, proving that Hook’s was more than just a pharmacy.

Origins

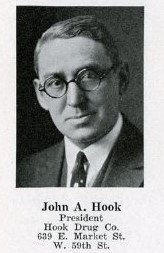

While Hook’s was a state-wide brand by the 1950s, its beginnings in the German American community of Indianapolis were far humbler. John August Hook was born on December 17, 1880, in Cincinnati, Ohio. His parents, August J. Hook and Margaret Hook, were both German immigrants who came to the United States in 1869, looking for a better life. His father was a beer brewer, who first laid down roots in Cincinnati before moving the family to Indianapolis by 1891. At the age of 19, John A. Hook knew exactly what his profession would be—pharmaceuticals. He graduated from the Cincinnati College of Pharmacy on June 9, 1900, the Indianapolis News reported. There, he earned three medals for his academic work, including “a gold medal for highest general average, a gold medal for highest materia medica, and silver medal for chemistry.” As a wunderkind of pharmacological science, Hook was eager to start serving his adopted community of Indianapolis.

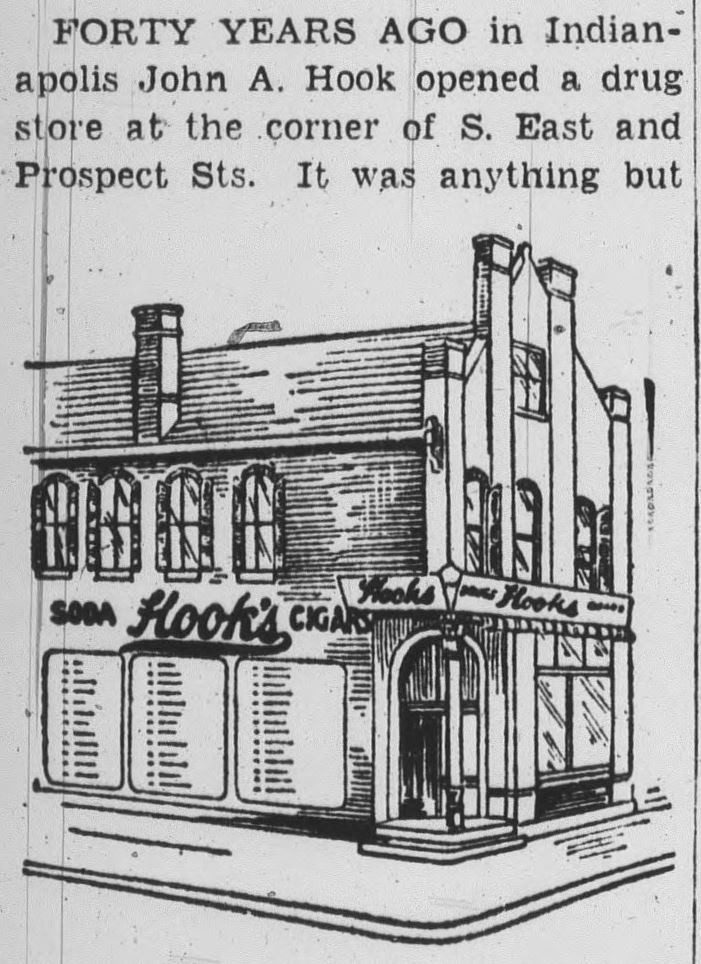

Shortly after graduating, Hook purchased a “Deutsche Apotheke” at 1101 South East Street from Louis Mattill, according to the Indiana Tribüne. Mattill had established the apothecary with his brother John as early as 1890 and nine years later John A. Hook bought out the company. As the son of German immigrants, Hook saw it as vital that he serve that community, which had greatly expanded in the Fountain Square neighborhood of Indianapolis, a part of the over 19,000 immigrants in the city by 1890.

While formative years at South East Street were successful, it wasn’t until he partnered with the enterprising Edward F. Roesch, who he hired in 1905 to manage a second store, that Hook’s business spread across Indianapolis.

The Early Years

Within 20 years, Hook and Roesch grew their drug store chain to over fourteen locations, and by the end of the 1920s, to forty-one. One essential component of this growth was prioritizing the design of new stores. It was here that Hook and Roesch partnered up with another legendary Indianapolis business, the architectural firm of Vonnegut, Bohn, & Mueller. Architects Kurt Vonnegut, Sr. (the father of acclaimed author Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.), Arthur Bohn, and Otto N. Mueller designed numerous drug stores for the company, either with completely new buildings or remodels of buildings that Hook’s Drugs previously purchased.

This partnership started as early as 1920, when Vonnegut, Bohn, and Mueller redesigned a saloon into a Hook’s drug store at Washington and Senate in Indianapolis. The next year, the firm remodeled a former storeroom at Pennsylvania and Washington.

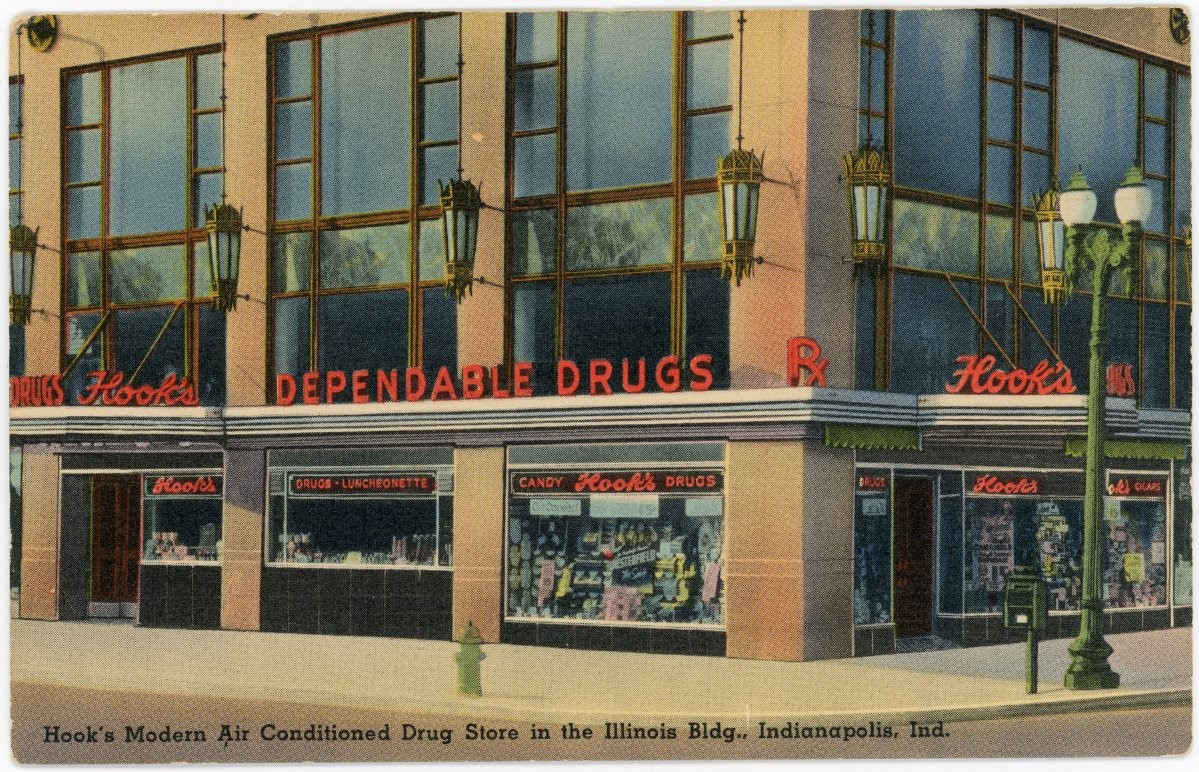

Despite the upheaval of the Great Depression in the 1930s, Hook’s continued to expand, with the help of Vonnegut, Bohn, and Mueller. The Indianapolis Star reported on April 15, 1935 that the architectural firm was “making alterations to the new Hook drug store at the southeast corner of Illinois and Ohio streets. In addition, this company is preparing plans for alterations to the Hook Drug Company store to be located at the northwest corner of Illinois and Market streets.” The Star in its October 24, 1937 edition ran an extensive article on Vonnegut, Bohn, and Mueller’s plans for a Hook drug store in the Broad Ripple section of Indianapolis. “Vonnegut, Bohn, and Mueller are the architects and have given every thought and consideration to the comfort of the customer,” wrote the Star, “such as soundproof ceiling, lighting, and attractive floor design.” In 1939, Hook’s commissioned Vonnegut & Bohn to a store at the northwest corner of Meridian and 22nd Street, which John Hook told the Times would be “one of our most outstanding stores and will be the last word in store design and equipment.” The thriving partnership between Hook’s and Vonnegut, Bohn, and Mueller lasted for nearly 20 years, with the latter’s innovative and attractive designs aiding the growth of the drug store chain.

Astounding Growth

With John Hook’s death in 1943 and Edward F. Roesch’s subsequent death in a car accident, their sons, August F. “Bud” Hook and Edward J. F. Roesch, took over the family business, as president and vice president, respectively. Their combined leadership led to a profound expansion of the business. As the Indianapolis Star wrote, “under the joint leadership of the two men the chain grew from an Indianapolis operation to a state-wide chain of stores.” In 1958, Hook’s operated 50-plus stores throughout Indiana with more than 1,000 employees. The company expanded its stores to “80 communities” by 1973, according to the Nappanee Advance-News.

This growth was not without its controversies. The employees of the Hook’s store in the Marwood neighborhood of Indianapolis ran a paid editorial in the Jewish Post on January 16, 1976, criticizing the company’s labor practices and its attempts to block unionization efforts. One hundred and fifty salesclerks of Hook’s “mann[ed] picket lines at many of the stores throughout Marion and Johnson Counties,” the editorial noted. It alleged that workers voted to be represented by the Retail Clerk’s Union-Local 725, and despite this vote’s certification by the local labor board, Hook’s “ignored this vote and refused to bargain” with them. It also accused Hook’s of hiring replacement labor and launching a public relations campaign against the strikers. The editorial declared “We ask that we be treated fairly and with respect by the Hook’s Drug Company . . . and that negotiations in good faith begin at once.” It is unclear whether the unionization effort was successful.

Despite these issues, Hook’s established itself by 1982 as one of the nation’s oldest chain drug store corporations, ranking 14th nationally in number of sales units and exceeding $260 million annually. The Illinoisan also noted that 30% of the firm’s business came from the prescription department, which was “nearly twice the national average.” With over 260 stores in Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio (its expansion outside of Indiana a result of the merger with SupeRx in 1986), Hook’s had become one of the largest drug store chains in the Midwest by the time it celebrated its 90th year of business in 1990.

The Innovative Community Leader

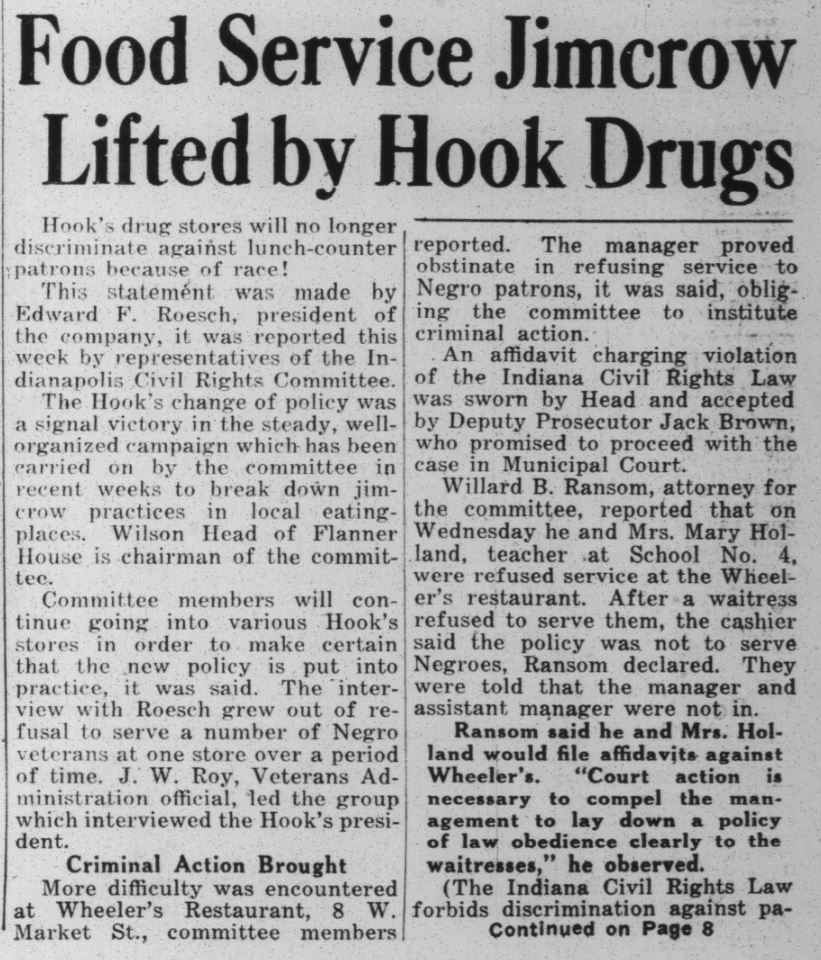

While labor disputes occurred during the company’s history, Hook’s nevertheless demonstrated a commitment to equal rights in Indianapolis. The firm desegregated its lunch counters at all locations in 1947, years before the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964. Black newspaper the Indianapolis Recorder carried coverage of Hook Drugs’ desegregation of their lunch counters, which the Indianapolis Civil Rights Committee fought tirelessly to achieve. As the Recorder noted, “committee members will continue going into various Hook’s stores in order to make certain that the new policy is put into practice.” Alongside equal access to its stores, the company promoted equal employment opportunities. In 1965, the Recorder wrote that Hook’s President Bud Hook served on a committee modeled after California’s Chamber of Commerce for Employment Opportunity. The committee’s goals included ensuring maximum employment of minority groups, improving communication “to make known employment need and opportunities,” and assisting other organizations in improving their minority employment programs.

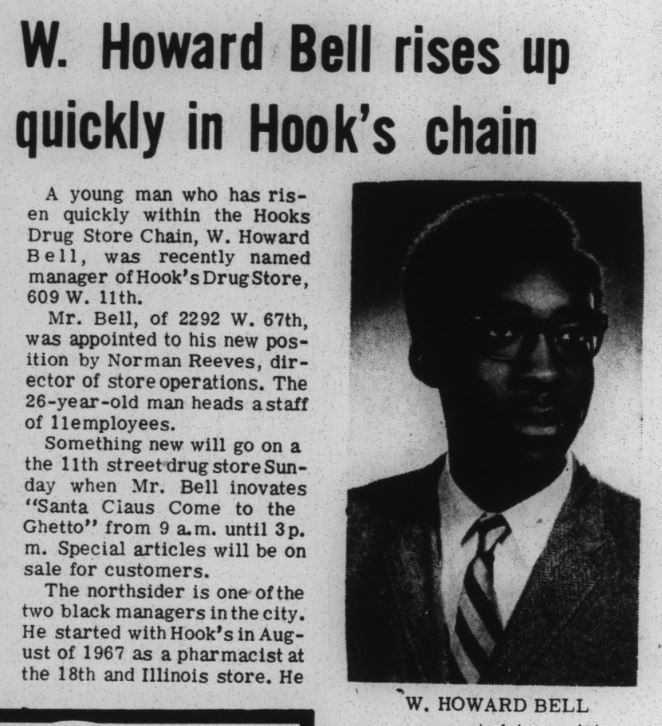

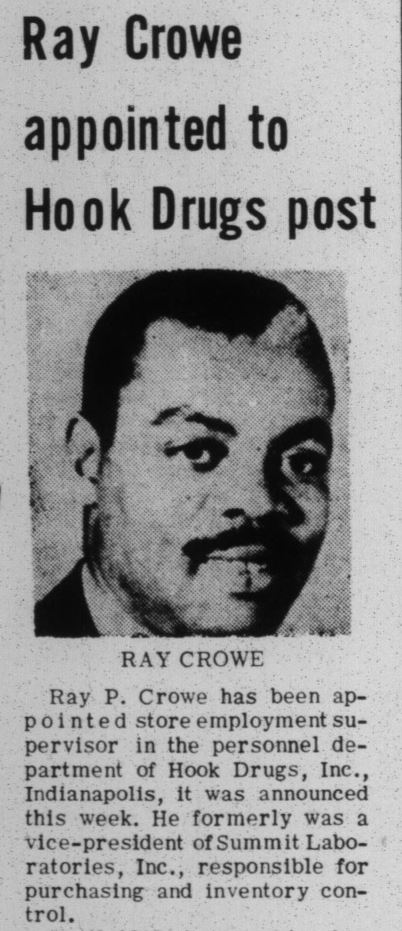

By 1969, Hook’s put these recommendations into practice in Indianapolis, increasing minority management to 10%. This had a direct impact on the community, as Black manager W. Howard Bell implemented the innovative “Santa Claus Comes to the Ghetto” sales initiative, which “aimed at giving customers a chance to obtain some items at reduced cost without waiting for the after-Christmas discount.” By 1972, Bell would own four drugstores of his own. Hook’s also promoted Black staff to corporate positions. In 1973, the firm appointed Ray Crowe, acclaimed athlete, coach, and politician, to store employment supervisor in the personnel department, as noted by the Indianapolis Recorder.

Hook’s also promoted broader public health initiatives. Starting in the late 1960s, Hook’s implemented a protected packaging program, developing a child-proof, lock-on cap and amber colored bottles that protected medicine from sunlight. Both were offered to customers at no extra charge. Hook’s advertisements in newspapers, including the Rushville Republican, Alexandria Times-Tribune, and the Indianapolis Star, attest to the “protection in packaging” program. Additionally, Hook’s provided a “poison counterdose chart” that “could prevent serious injury or even save a life should accidental poisoning occur in your home,” as printed in the Indianapolis Star.

Alongside drug safety, Hook’s was active in drug misuse/abuse prevention and education, which is more crucial than ever as drug abuse is at epidemic levels. Pharmacists routinely spoke to community organizations and received training from the Pharmacists Against Drug Abuse Foundation and the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy. As the Indianapolis Star reported in 1971, “Many Hook’s pharmacists serving in stores and in administrative positions have given countless talks to schools, churches, and other social action groups” about drug abuse and its prevention.

In 1980, Hook’s sponsored a state-wide poison control initiative that “include[d] a $40,000 grant. . . to establish a statewide network of regional hospital emergency treatment centers to provide close at hand emergency treatment throughout the state,” as noted in the Nappanee Advance-News. The next year, Hook’s co-sponsored a 10-week “anti-drug abuse public service campaign” entitled “It Takes Guts to Say No.” Hook’s Executive Vice President Newell Hall said of the initiative to the Indianapolis Recorder, “as a corporation we are committed to providing professional prescription service to our communities and feel it is our duty to inform the public about the hazards of substance abuse.”

Hook’s also distributed informative brochures to customers about symptoms of drug abuse and what parents can do if they suspect their children of abusing drugs. James M. Rogers, Hook’s vice president of public relations, told the Banner, “Our brochure offers facts and common-sense information for parents and children alike. If prevention doesn’t work, early detection is critical.” Hook’s “Parent Guide to Drug Abuse” pamphlets were available for free in all their stores.

While not always progressive on labor issues, Hook’s advancements of civil rights, innovative packaging programs, and drug abuse and prevention initiatives solidified the company as a trusted community leader for decades.

Hook’s Legacy

The end of Hook’s Drugs came like the end of so many businesses during the 1980s and 1990s: through corporate mergers. In 1985, Hook Drugs, Inc. merged with the Cincinnati, Ohio-based grocery chain Kroger, which was the “second largest supermarket chain,” according to the Nappanee Advance-News. This merger would end in 1986, when Hook’s and the SupeRx drug store chain, both owned by Kroger, split off into their own firm, Hook-SupeRx, Inc.

On April 4, 1994, Revco, a drugstore chain based out of Twinsburg, Ohio, announced its plan to buy Hook-SupeRx, Inc. for an estimated $600 million. The merger was finalized in July of that year. Unfortunately, this consolidation came with job cuts and store closures.

Less than three years later, on February 7, 1997, Rhode-Island based CVS purchased Revco at a cost at $2.8 billion, according to the Indianapolis News, and with it, phased out the use of the Hook’s brand. While the legendary name is gone, many former Hook’s locations still operate today under the CVS banner.

Although no longer being in business, the company’s history is tangible at the Hook’s Drug Store Museum, which opened at the 1966 Indiana State Fair. Originally a three-month exhibition, it eventually became a permanent attraction. The museum recreates what a Hook’s drug store was like in the early 1900s and remains in operation today at its original location at the fairgrounds. Reflecting on its success years later, journalist Judy observed, “the Hook’s Historical Drugstore and Pharmacy Museum has become a national acclaimed tourist attraction. It has garnered many awards from both pharmaceutical and historical organizations, and millions of individuals have visited from every state and many foreign countries.”

In its 90-plus years, Hook’s Drugs went from one building in Fountain Square to one of the largest drug store chains in the United States, with over 380 locations and millions in sales. While the company faltered on labor issues, Hook’s commitment to civil rights and drug abuse prevention made the brand synonymous with fairness, kindness, and the personal touch. As the collective memory of Hook’s fades, it is important to recognize its special place in the history of Indiana businesses. Also, we must remember its motto from years ago, words that rang through its many ads and embodied its ethos— “We like to see you smile!”

![Instep-arch support patent [marketed as Foot-Eazer], Publication date April 25, 1911, accessed Google Patents](http://blog.newspapers.library.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/1911-Instep-Patent.png)

![Elevated Railroad Station at East Madison Boulevard and Wells Street [near Scholl's building] November 1, 1913, Chicago Daily News Photograph, Chicago History Museum, accessed Explore Chicago Collections, explore.chicagocollections.org/image/chicagohistory/71/qr4p14f/](http://blog.newspapers.library.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/train-station-at-Wells-and-Madison-CHicaho-History-Museum-300x243.png)