“West Hammond has been electrified of late by what a woman—a woman of intelligence, of action and indomitable courage—can accomplish.”

-Munster Times, 1911

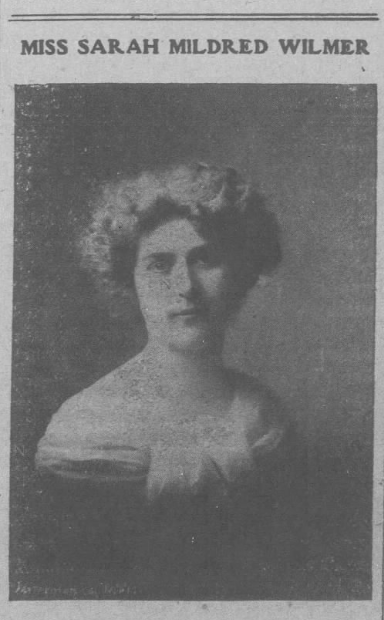

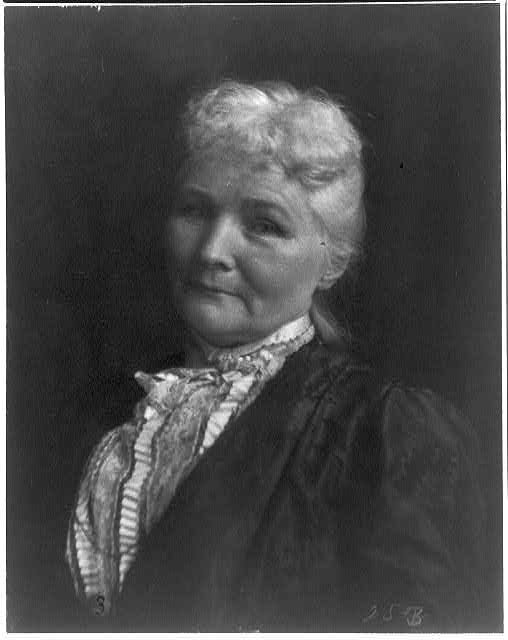

The woman described by the Times was one Virginia Brooks, also dubbed “Joan of Arc” of the burgeoning village of West Hammond. She was determined to end the mistreatment of vulnerable residents and expel corrupt politicians from West Hammond (now Calumet City)—an Illinois town that overlapped into Indiana. Brooks did this by delivering speeches in barrooms, confronting law enforcement officials, and founding her own publication. After realizing the limitations of protests and the press, Brooks embraced the Women’s Suffrage Movement as means of change, leading the charge alongside suffragists like Ida B. Wells.

Brooks was in her early 20s and studying music in Chicago when she received a notification that drew her to West Hammond. According to the Indianapolis News, upon her father’s death, she and her mother, Flora, inherited property in the village. Alerted to $20,000 worth of special assessments against it, they made a trip to the area to investigate. Virginia was stunned by the dilapidated condition of the village and prevalence of casinos and barrooms. Thus, began her reform work.

In early 1911, West Hammond was on the precipice of becoming a city, pending a special municipal election. However, Brooks, with the help of her mother, mounted a campaign to maintain its status as a village. Should the area become a city, vice would essentially be institutionalized and corruption amplified. Preventing this would be quite the feat, as the Times wrote, “The political machine was dead against” the women and their allies.

Brooks gathered locals at Mika’s Hall to discuss the upcoming election. She and organizer August Kamradt spoke to the primarily Polish audience about how city leaders used taxpayers’ money for their own gain, leaving sewers and sidewalks crumbling. Brooks’s sentiments were extremely well-received, and she persuaded attendees to sign a petition asking the State Attorney of Cook County to investigate public officials’ use of tax money.

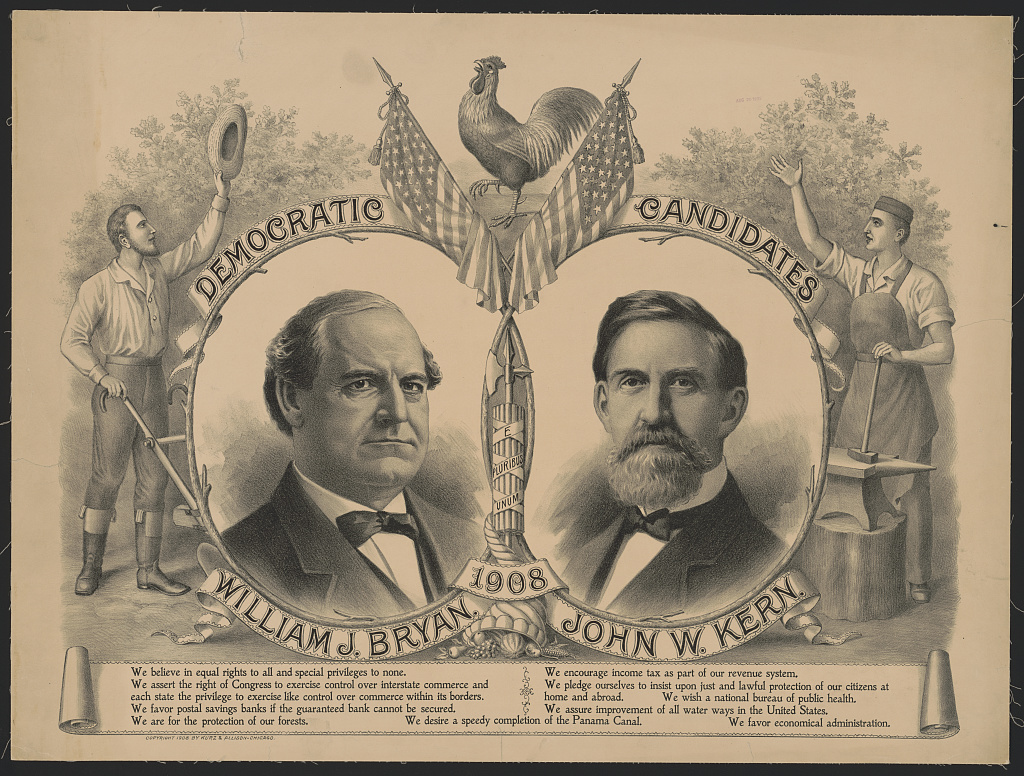

West Hammond’s 4,000 residents, many of whom were European immigrants, seemingly had little choice but to pay constantly-increasing rent and “special assessments,” which impoverished them further. Despite this, the Huntington Herald noted that male villagers were fairly apathetic until “this young girl. . . . Virginia Brooks has set in motion the levers that work mighty changes.” As the election approached, she spoke at barrooms late into the night, promising that if local efforts failed, she would “appeal to the president and the White House. And if that, too, is useless, she will take the law in her own hands.”

Brooks’s radical strategies elicited death threats. She laughed these off, although she did appreciate the young men who “formed a bodyguard” around her. On election day, she appealed to voters until the moment they stepped into the voting booth, which was monitored by two deputies Brooks had summoned to prevent fraud.

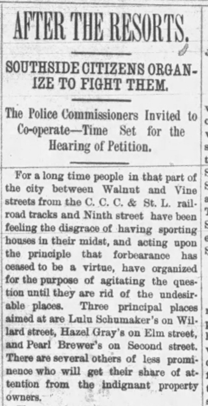

Despite the valiant fight, Brooks’s faction lost the election, and voters opted for city government by a vote of 227-196. In a scene seemingly plucked from a movie, just as victors celebrated into the night with a bonfire and parade, detectives from the State’s Attorney’s office infiltrated West Hammond. Brooks’s petition had born fruit. The Chicago Tribune reported that the detectives served subpoenas to “keepers of alleged disorderly houses and places where slot machines were found.” Opponents retaliated with more death threats and libel suits. Brooks was far from alone in her convictions, however. One “Taxpayer of West Hammond” wrote to the Hammond Times that “If ‘Virginia is crazy,’ the rest of us should ‘get the bug’ and help to clean things up.”

Following the election, Brooks leveraged another tool in her fight—the media. She established a semi-weekly publication called the Searchlight. Brooks told the Chicago Tribune that she would only publish articles that were backed by evidence, with the goal to “fight the grafters primarily and promote the interests of the working people who make up the bulk of the population.”

In addition to leveraging the press, Brooks engaged in physical confrontation as a means to effect change. In March of 1911, she and her “broom brigade,” composed of about twenty women, halted a paving project at One Hundred and Fifty-Fifth Street. With municipal contract in hand, Brooks and her squadron—equipped with mops, rolling pins, and brooms—sat on piles of bricks, refusing to move for hours. They sat in protest of the city’s decision to hire laborers to install “graft bought” bricks of poor quality five inches too low. Not only that, but the city charged tax payers an exorbitant amount to do so. When workers’ attempts to appeal to the women failed, they summoned the police. Local newspapers reported, perhaps somewhat sensationally, that a fight for the ages ensued. The Indianapolis News relayed:

When the women refused to leave, the police tried to drive them off with clubs, and a hand-to-hand conflict followed. Several of the women were put out of the battle with slight injuries and their male supporters, who came to their aid when the police attacked, were badly beaten.

After combat and bloodshed, the police left and returned with arrest warrants. Virginia Brooks gladly went to jail, hoping her arrest would engender more support for the cause. She was correct, as the Hammond Times reported that the following day, “broad shouldered, firm mouthed women” returned to the work site and resumed the stand-in.

The intensity of the fight carried over to Brooks’s April 3rd trial, for which she was charged with disturbing the peace. According to the Times, the courtroom floors and walls were lined with observers, many of whom were women who “shoved and crowded among the men” to take in every word. Officer John Okraj testified that Brooks had struck him in the face after being placed under arrest. The Times reported that Brooks, “an excellent witness in her own behalf,” testified that Officer Okraj likely didn’t know his own strength, and that he hurt her when he forcefully grabbed her neck. Her response was “but a primitive action, an instinctive motion, which anyone would make when attacked from the rear.”

Ultimately, the jury found Brooks guilty, but she was fined only $1. Just as jurors convicted her, she received word that State Attorney Wayman pledged to investigate graft charges in the village. This investigation likely spurred the indictment of City Clerk Martin Finneran in May. He was charged with collecting and depositing taxes from the Michigan Central Railroad into his personal account one week after he was dismissed from the office of West Hammond village collector. And, just a few months after Brooks’s trial, her battle against exploitation and “exorbitant special assessments” paid off. The Hammond Times reported that a county circuit court judge ruled in her favor regarding the work at One Hundred and Fifty-Fifth, resulting in a 30% reduction “of the original cost and an extra assessment of about $5,000.”

Overjoyed taxpayers organized a band concert in celebration. Her widely-publicized achievements attracted love interests and generated about fifty marriage proposals, according to the Chicago Tribune. She responded “‘I wouldn’t marry the best man alive'” because “politics comes before love with me.”

Instead, Brooks focused on ousting the old village leadership to ensure that the newly-dubbed city would be managed by reputable councilors. According to the Evansville Press, in August 1911, she threatened the village council president that if he refused to convene a municipal election she would “expose the whole outfit.” The paper reported tellingly that immediately after her threat, the “president announced that he was sick and would have to go to the hospital for a couple of months.”

While awaiting word of a municipal election, Brooks led the charge in another election. She convened a mass meeting at Mika’s to persuade residents to vote against a new proposal by the village board. It would tax residents to build a private power line, which would solely benefit the Interstate Electrical Company. Despite being issued “mutilated ballots,” indignant voters managed to defeat the board’s proposal. The Indianapolis News noted that Brooks hired carriages to take voters to the polls, resulting in the “biggest vote ever known in the city’s history.” In fact, local papers suggested that such a resounding defeat could result in her nomination for mayor of West Hammond.

Realizing that this could never be achieved without the female vote, Brooks embraced the women’s suffrage movement, which she had previously dismissed as unnecessary. Mass meetings and protests could only go so far without women’s voting rights. In the spring of 1912, she infiltrated Chicago restaurants to lay out the urgent need for enfranchisement. The Munster Times noted “instead of waiting until her audience came to her she took her speech to the places where sufficient numbers of persons were gathered to make audiences for her.” Her speeches were met with resounding applause from diners.

Immediately after this brief crusade, organizers asked Brooks to speak at the Indiana’s Women’s Franchise League annual convention in Indianapolis. Of the prominent Hoosier suffrage leaders, like Dr. Amelia Keller and Grace Julian Clarke, the Indianapolis News reported that Brooks “easily attracted the most attention at the convention.” She described for her fellow suffragists how she had mobilized for reform, gripping them with the story of hand-to-hand combat in West Hammond. However, she had recently embraced a strategy more familiar to audience members—many of whom were upper-middleclass women— lobbying state senators. Brooks told convention-goers, “The women need the ballot, and the country needs women voters . . . We don’t want to mix in the dirty politics of the men, but we do want to work with them to make things better.”

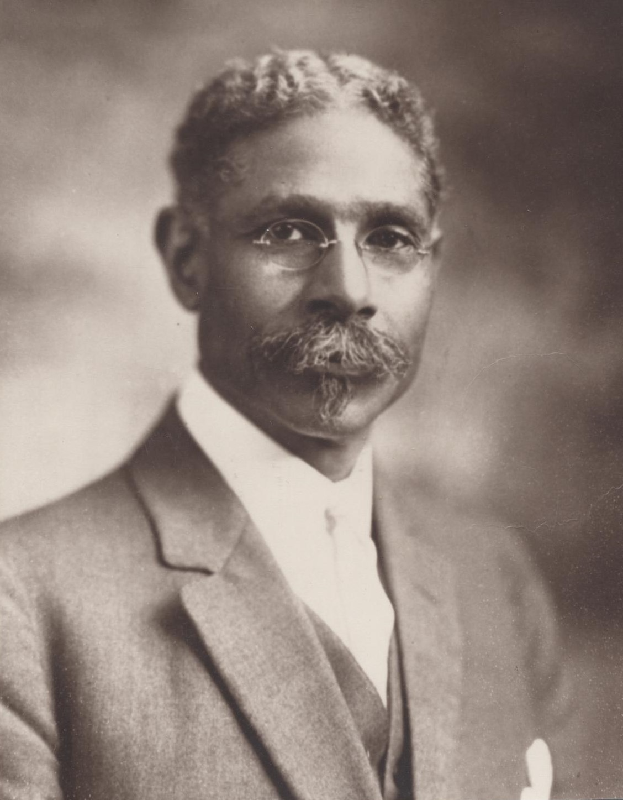

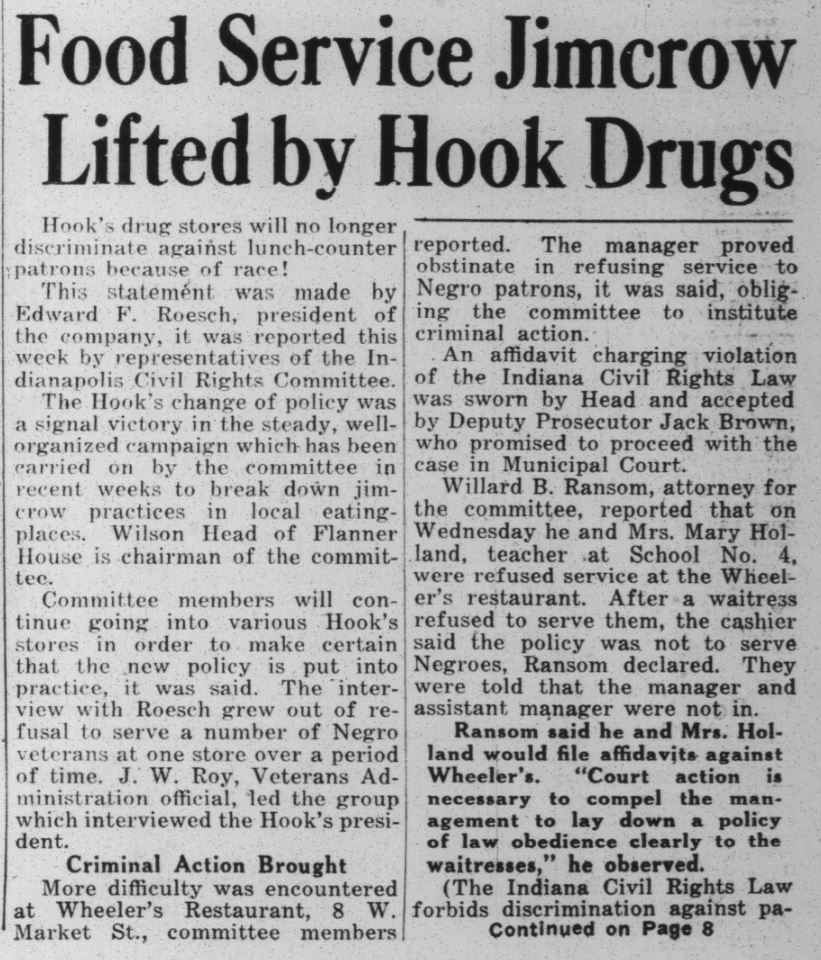

Dr. Hannah Graham, president of Indiana’s other major suffrage organization, the Equal Suffrage Association (ESA), invited Brooks to speak at an ESA meeting, along with union leader Frank Hayes, Indianapolis Mayor Lew Shank, and prominent Black attorney F.B. Ransom. Perhaps this meeting of the minds and exchange of ideas inspired Brooks to pursue law. According to the Indianapolis Star, Brooks told Dr. Graham, “I have property, and in my fights against corrupt politicians a knowledge of law certainly would help me.” Dr. Graham revealed that she was currently studying at the Indiana Law School and suggested the two drive there that very day. Brooks took her up on the suggestion and met with faculty, telling them she wanted to study law to aid the “poor Polish people in West Hammond.” She became the third woman to enroll in the junior class.

Brooks’s experience mobilizing at the local and state level served her well at the famed National American Woman Suffrage Association parade in Washington, D.C. She joined thousands of women from across the country on March 3, 1913, the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Hoping to draw widespread attention to the need for enfranchisement, the women paraded throughout the nation’s capital, some in costume and others hoisting banners.

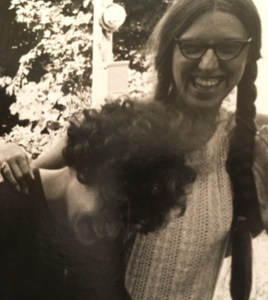

Brooks and Belle Squires led the Illinois delegation. According to Ron Grossman’s 2020 Chicago Tribune article, organizers ordered Brooks’s friend and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells to march at the back of the parade with the other Black suffragists. Rather than concede, Wells opted to sit out altogether, despite Brooks’s insistence that they march together. At the last minute, Wells ran towards Squires and Brooks, and the three women flanked the head of the delegation. Despite violence perpetrated against some of the marchers, the 1913 parade catalyzed public support for women’s suffrage and reinvigorated the movement.

The parade may have been the zenith of Brooks’s activism. Just one month later—despite her earlier pronouncements about marriage—she wed Chicago Tribune photographer Charles Washburne and the couple relocated to Chicago. Brooks said of West Hammond, “‘The fight is over there, and I guess we have won. We are going to settle down.'” She went on to write for the Tribune, volunteer at the Hull House, and lecture at chautauquas. She drew upon her experiences to author books about social issues like My Battle With Vice and The Little Lost Sister. Around 1918, Virginia relocated to Portland, Oregon with her mother and son, Brooks. After months of illness, she passed away at the age of 42, just a few months before the stock market crash. She likely would have agitated relentlessly for relief like Hoosier reformer Theodore Luesse did during the Great Depression. Despite a life cut short, Brooks demanded accountability and fearlessly effected change in The Region.

Sources:

“The Right Sort of Courage,” The Times (Munster, IN), January 5, 1911, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Villagers Swarm to Gathering,” The Times (Munster, IN), January 26, 1911, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Miss Virginia Brooks, West Hammond’s Joan of Arc,” The Times (Munster, IN), January 28, 1911, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Virginia Brooks Politician,” Huntington Herald, January 31, 1911, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Death Threats Against Girl,” Fort Wayne News, January 31, 1911, 10, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Girl is Defeated in Reform Fight,” Chicago Tribune, February 1, 1911, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Village is to Become City in May,” The Times (Hammond, IN), February 1, 1911, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Sued by City Officials,” News-Democrat (Paducah, KY), February 4, 1911, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

Editorial by “A Taxpayer of West Hammond,” “Ought to Clean Up,” The Times (Hammond, IN), February 6, 1911, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Virginia Brooks Starts as Editor to Rid Her Town of Election Frauds,” Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer, February 13, 1911, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

“One Girl’s Sunday Fight to Clean Up ‘The Rottenest Town in the Country,'” Chicago Sunday Tribune, March 5, 1911, 47, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Girl Routs Paving Gang,” Chicago Tribune, March 25, 1911, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Riot in Village; Girl is Jailed,” The Times (Hammond, IN), March 25, 1911, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Girl Leader of Mob Thrown in Jail After Day of Bloodshed,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), March 26, 1911, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Comedy Injected in Trial,” The Times (Hammond, IN), April 4, 1911, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Virginia Brooks is Fined by Jury,” Chicago Tribune, April 6, 1911, 9, accessed Newspapers.com.

United Press, “Village Joan of Arc After the Grafters,” Evansville Press, August 16, 1911, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Virginia Brooks Still Active,” South Bend Tribune, May 25, 1911, 14, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Miss Virginia Brooks Wins Another Battle,” The Times (Hammond, IN), July 11, 1911, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Miss Brooks vs. Woman Suffrage,” The Times (Hammond, IN), August 14, 1911, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.

“New War Stirs West Hammond,” Chicago Tribune, August 14, 1911, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Mass Meeting Across the Line,” The Times (Hammond, IN), November 1, 1911, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Bond Issue in Fought,” The Times (Hammond, IN), November 7, 1911, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Virginia Books Wins Fight Against Bonds,” Indianapolis News, November 8, 1911, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Miss Brooks of Hammond,” Indianapolis Star, November 15, 1911, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Settlement was Nicely Remembered,” The Times (Munster, IN), January 5, 1912, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Miss Virginia Brooks Campaigning,” Fort Wayne Sentinel, January 10, 1912, 12, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Suffrage ‘Joan of Arc’ Speaking to Restaurant Guests,” The Times (Munster, IN), April 2, 1912, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

“New Constitution Desired by Women,” Indianapolis News, April 4, 1912, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

Betty Blythe, “Miss Brooks, Suffrage ‘Joan of Arc,’ Tells How She Rules West Hammond,” Indianapolis Star, April 4, 1912, 9, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Graft is Scored by Miss Brooks in Ballot Plea,” Indianapolis Star, April 4, 1912, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Women Ignored by ‘Constitution,'” South Bend Tribune, April 4, 1912, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Man Thrown into Ditch,” Indianapolis News, April 23, 1912, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Warm Supporter Cause of Suffrage,” Indianapolis News, April 24, 1912, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Miss Brooks Plans to Study Law Here,” Indianapolis Star, April 25, 1912, 10, accessed Newspapers.com.

Chicago Daily Tribune, March 5, 1913, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

Virginia Brooks, My Battles with Vice (Macaulay Co., 1915), accessed Archive.org.

“Mrs. Virginia Washburne, Writer, Lecturer, is Dead,” Oregon Daily Journal, July 15, 1929, 7, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Prominent Woman Dies,” The Oregonian, July 18, 1929, 14, accessed Newspapers.com.

Ron Grossman, “Flashback: Fighting for the Vote and Against Vice: Virginia Brooks was the Chicago Area’s Own ‘Joan of Arc,'” Chicago Tribune, August 21, 2020, accessed chicagotribune.com.