Lauana Creel approached the porch and rang the doorbell of a prominent Evansville citizen she had arranged to interview. The WPA’s Federal Writer’s Project had tasked her with interviewing formerly enslaved Americans in order to document their experiences and perspectives. On this particular day, Dr. George Buckner would be the subject of a series of interviews.

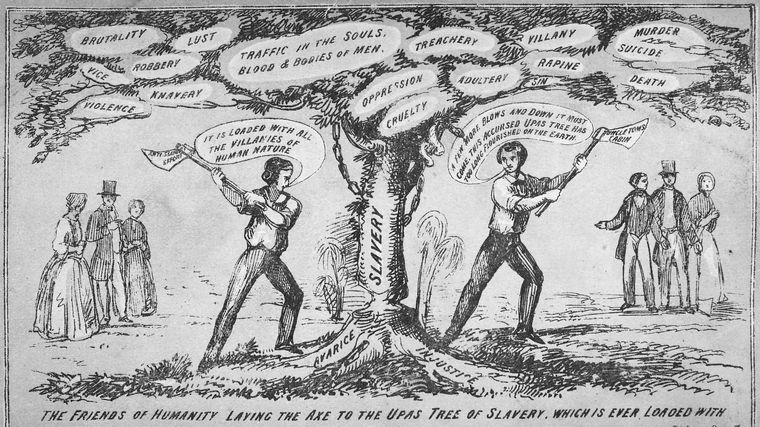

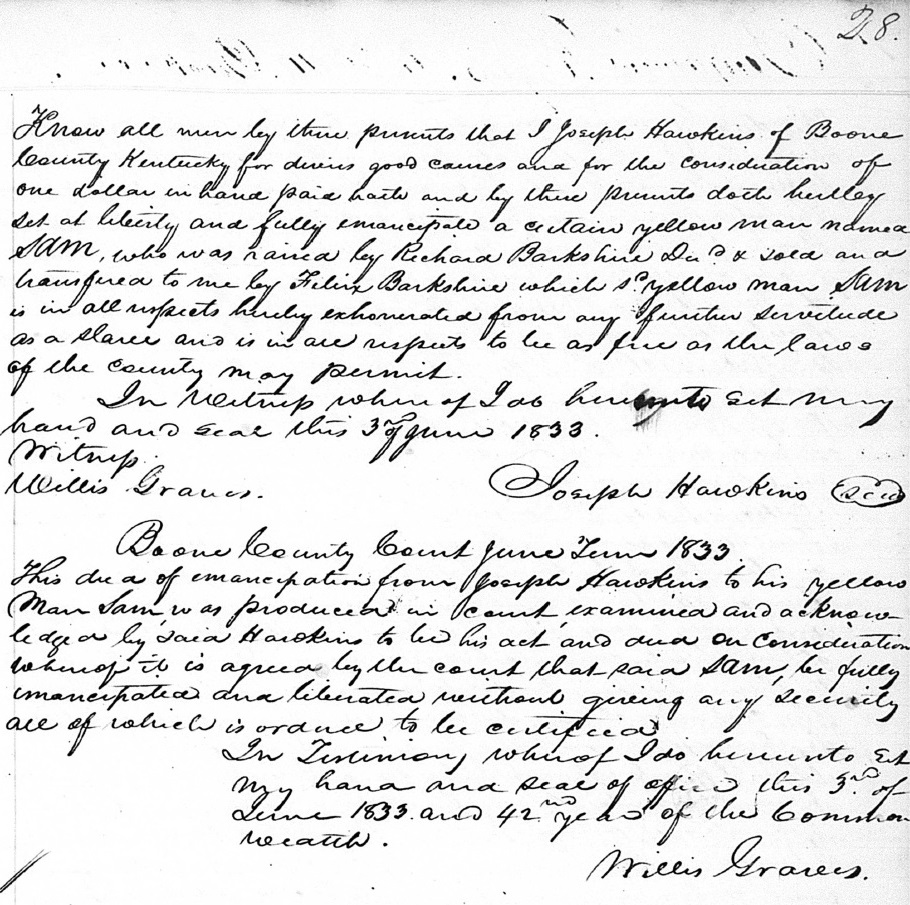

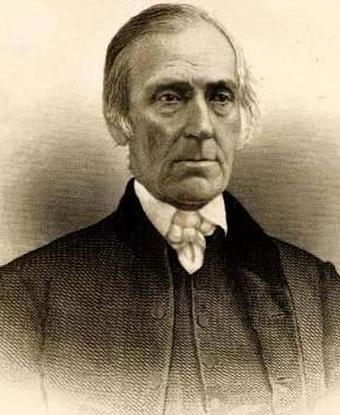

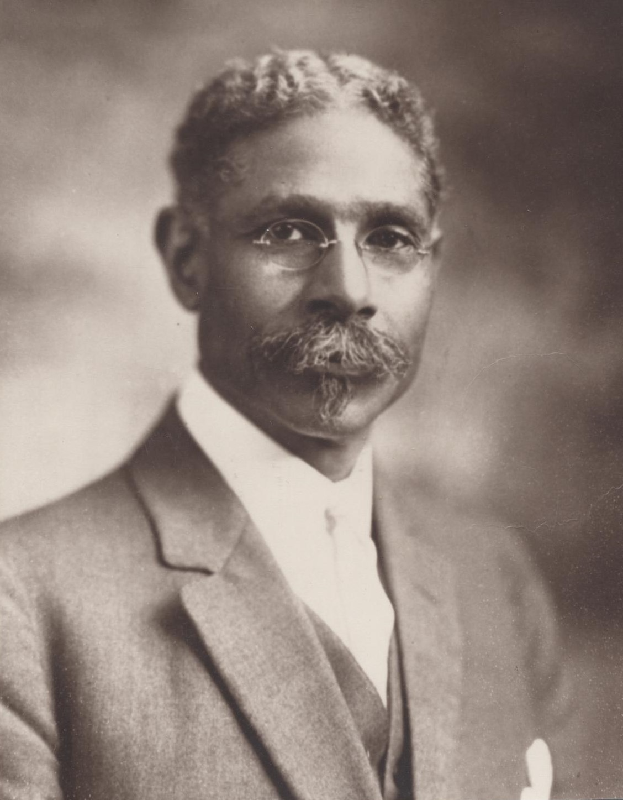

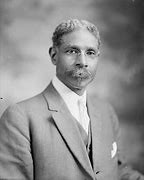

Creel learned that George Washington Buckner was born into slavery on a small farm in Greensburg, Kentucky around 1853. He lived in a single-room cabin with his mother, step-father, and many siblings. In poor health and lacking surgical or medical assistance, his mother became bed-ridden. Given these circumstances, the trajectory of his life was seemingly implausible. From obtaining higher education, to becoming a physician and political activist, to building up his own community, Dr. Buckner exemplified what was possible despite being born into that “peculiar institution.” The Evansville Press aptly noted that he experienced “a world which offered few opportunities for men of his race. He overcame these severe handicaps and his influence for the improvement of the lot of all Negroes has been powerful.”

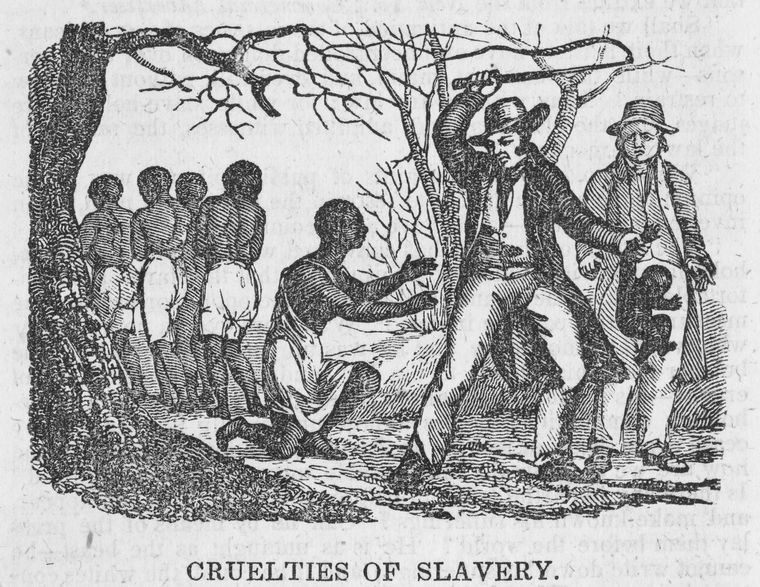

During his childhood, George was “presented” to his master’s son, “Mars” Dickie Buckner. Despite being roughly the same age, George was required to do whatever Mars requested, like polishing his boots and putting away his toys. Although his “master,” Mars also served as a playmate and companion of George, who later described their relationship as sympathetic and loving. Unfortunately, George’s only playmate passed away from illness. Mars’s death caused George Buckner great sadness. He claimed to have seen Mars’s ghost one night, pressed against the window of the room in which he died. The death of Mars affected George deeply, and drove him to become a physician.

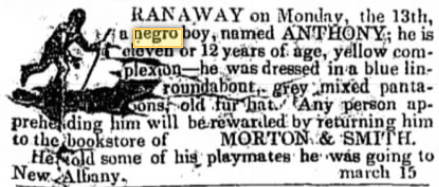

Compounding his loneliness, Buckner’s sister was sold to another family when the master’s daughter got married. Buckner told Creel, “It always filled us with sorrow when we were separated either by circumstances of marriage or death. Although we were not properly housed, properly nourished nor properly clothed we loved each other and loved our cabin homes and were unhappy when compelled to part.”

While Buckner experienced personal tragedy, the nation had also plunged into crisis. Several of Buckner’s uncles fled North to enlist in the Union Army during the Civil War. In his interview, Buckner talked about the night they decided to escape enslavement and join the war effort, stating:

I had heard my parents talk of the war but it did not seem real to me until one night when mother came to the pallet where we slept and called to us ‘Get up and tell our uncles good-bye.’ Then four startled little children arose. Mother was standing in the room with a candle or a sort of torch made from grease drippings and old pieces of cloth . . . and there stood her four brothers, Jacob, John, Bill, and Isaac all with the light of adventure shining upon their mulatto countenances. They were starting away to fight for their liberties and we were greatly impressed.

Ultimately, Jacob was too old to serve and Isaac too young, but George’s two other uncles were accepted into the Army. According to the WPA interview, one was killed in battle and the other fought and returned home unwounded. Black individuals like George’s uncles, helped end the war and the institution of slavery.

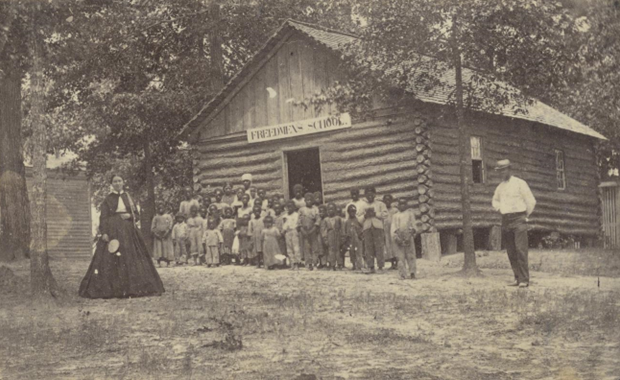

When the war ended, George was not yet a teenager and struggled to survive. He taught himself to read with a spelling book, and his literacy became a valuable skill. In 1867, he furthered his education by taking courses through the Freedmen’s Bureau, an agency created immediately after emancipation to help Black individuals get jobs, learn basic skills like reading and writing, and help them understand their rights. He began working for the Bureau in Greensburg, Kentucky, teaching other young, formerly-enslaved individuals to read and write. Buckner told Creel that he boarded with a family in a cramped cabin, sleeping in a “dark uncomfortable loft where a comfort and a straw bed.”

Buckner furthered his education after moving to Indianapolis, where he encountered Robert Bruce Bagby, principal of the only Black school in the city. Buckner said Bagby was the “first educated Negro he had ever met.” Bagby himself was born into slavery in Virginia, and his parents purchased their family’s freedom in 1857. He then earned a college degree and joined Indiana’s only Black regiment during the Civil War. After studying at Bagner’s school, Buckner made ends meet by working at restaurants and hotels as a “house boy,” or domestic servant. After earning enough money working menial jobs, Buckner went on to study at the Terre Haute Normal School (later Indiana State University), graduating in 1871.

He went on to teach Black students at Vincennes University. While he was earnest about advancing his educational career, another part of him longed to do something else. He wanted to provide essential medical care, motivated by the loss he experienced in his own life. He recalled:

I was interested in the young people and anxious for their advancement but the suffering endured by my invalid mother, who had passed into the great beyond, and the memory of little Master Dickie’s lingering illness and untimely death would not desert my consciousness. I determined to take up the study of medical practice and surgery which I did.

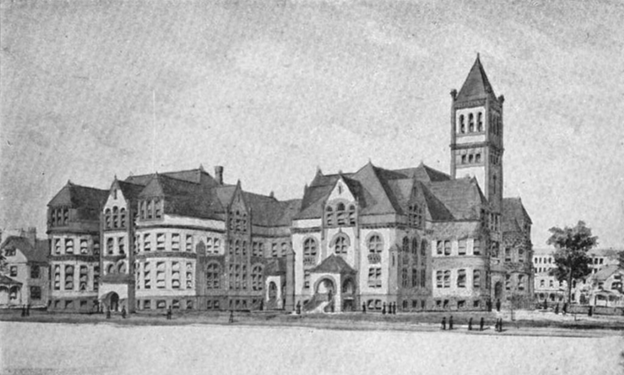

In 1890, Buckner earned his M.D. from the Indiana Eclectic Medical College in Indianapolis (which became part of Indiana State University). Dr. Buckner practiced medicine in the city for a year, cultivating a positive reputation among the Black community. He transferred his practice to Evansville, where he spent the rest of his life. This likely made him the first licensed Black doctor to practice in the city. Buckner’s role as a physician was crucial, since Black patients could only be treated by Black doctors, many of whom lacked the same resources as white practitioners. According to a UCLA study, Black men comprised only four percent of all doctors and physicians in the U.S. during the time Buckner practiced. He was a vital member of the Black community, someone who they literally could not have lived without.

He also aided his community in other ways. Understanding the importance of education through his own experiences, Buckner dedicated himself to helping other young people get an education. He helped establish the Cherry Street YMCA to give Black children a place to play and learn. He was also the principal of the Independence Colored School, putting his educational background to good use. Buckner served as a trustee at the local Alexander Chapel AME church. He enlisted the help of hundreds of Black residents in the Colored Akin Club in preparation for a local municipal election.

While Evansville provided a change of pace for Buckner, from the hustle and bustle of Indianapolis, there he encountered not only casual racism, but threats against his life, for some of his political views. Buckner was an ardent Democrat, which made him a minority in the Black community. In a local Democratic newspaper, he wrote a column called “Colored Folks” and became well known for his outspoken views. He staunchly supported Woodrow Wilson and, later, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. A contentious issue that he fought against during his time was vote-buying, a process whereby a local political machine used intimidation or bribery to sway voters to their side. Black Americans were often a target for their perceived desperation. According to Bucker’s interview, he viewed vote-buying as a serious roadblock for self-determination and encouraged them not to be persuaded by bad actors, stating:

The negro youths are especially subject to propaganda of the four-flusher [fraud; huckster] for their home influence is, to say the least, negative. Their opportunities limited, their education neglected and they are easily aroused by the meddling influence of the vote-getter and the traitor. I would to God that their eyes might be opened to the light.

Buckner’s Democratic leanings were not always looked on kindly, as he describes having to hire a bodyguard to keep him and his family from harm. He told Creel that he brought security to professional and social events to:

prevent meeting physical violence to myself or family when political factions were virtually at war within the area of Evansville. The influence of political captains had brought about the dreadful condition and ignorant Negroes responded to their political graft, without realizing who had befriended them in need.

Despite criticism and threats, his bravery and moral conviction also opened new avenues for advancement. He caught the attention of several prominent Democrats in Indiana, including John W. Boehne, with whom he would develop a friendship. Boehne was a Congressman and Mayor of Evansville from 1905 to 1908. This connection helped further Buckner’s burgeoning political career.

In 1913, the Wilson Administration tasked U.S. Senators from Indiana with selecting the Minister to Liberia. According to the Indianapolis Star, Dr. Buckner was appointed because he “stands high among members of his race, while his Democracy is vouched for as the right brand by the Democratic leaders of the Indiana ‘pocket.’” The paper noted that the “number of negroes who would be willing to fight and die for the Democratic party” was notably small. In fact, former Rep. John W. Boehne, who endorsed Buckner for the appointment, stated that Buckner was loyal to the party “’at times when it almost cost a negro his life to be a Democrat.’”

The Star reported a few months later that “Secretary of the Treasury McAdoo is hearing echoes of a political insurrection among Indiana negroes over the appointment” of Buckner, whom they felt was “not entitled” to “this big job.” Other Black residents cheered the announcement, throwing a reception to celebrate Dr. Buckner’s breaking of racial barriers, regardless of political affiliation. His appointment occurred, fittingly, just days before Evansville’s Emancipation Day celebration, at which the “newly appointed United State Minister to Liberia” spoke.

In the early 1800s, the American Colonization Society sought to establish a colony, Liberia, in Africa in which thousands of freed Black individuals could establish a community.* By the time Dr. Buckner arrived in Liberia, it was known as “the negro republic.” The Tacoma Daily News described it as “the only country in the world that is owned and governed by negroes.” To say Black Americans thrived in Liberia would be inaccurate. According to the Daily News, the Afro-American League of Evansville submitted a petition to U.S. Congress, alerting legislators to challenging conditions, which included the climate, predatory animals, diseases, resistance from natives resulted in hardship, and even death. Additionally, Liberia was caught in the crosshairs of international conflict that would culminate in World War I.

In its petition, the Afro-American League noted that Liberia was situated between “the British and the French possessions, which are continuously encroaching upon her territory.” War exacerbated the conditions in Liberia, especially as “merchant vessels have ceased to appear upon the coast of Liberia, where our own people in the dark continent are struggling for existence and where this war is causing untold numbers to perish.” The League appealed to Congress, asking that “the European and American capitalists be prohibited, if possible, from plunging Liberia into the yawning abyss they have apparently created for her.”

It was this backdrop from which Dr. Buckner began his diplomatic career. Many foreign actors were trying to change Liberia’s nominally “neutral” stance on the war. The Evansville Courier reported that although Buckner did not witness war actions, “he saw evidences of war all along the trip. On the west coast of Africa he saw the remains of a wrecked German cruiser, sunk early in the war, and at Gibraltar he saw the British battleship Inflexible, which was damaged in the engagements in the Dardanelles.” Buckner tried to maintain an independent attitude, difficult, considering his inexperience with diplomacy.

He was frustrated with the rampant corruption and gerrymandering of the political system, which exacerbated dysfunction and unrest. This was something that past ministers to Liberia also noted. Dr. Buckner also suffered from two attacks of African Fever. He resigned from the post prematurely in 1915. Despite some hardships, he told Creel that he “cherishes the experiences gained while abroad.” According to one newspaper, Buckner told a friend privately, “I had rather make less money and remain where I can give my children a father’s advice.” Buckner had four children and clearly prioritized raising them over his diplomatic post. This was quite the sacrifice to make, considering his post granted him a salary of $5,000 (about $154,619 today). The Evansville Press praised his work as a diplomat, noting his “honesty and integrity are unassailable.” Similarly, the Pennsylvania Altoona Tribune marveled that although born into slavery, “Today he is a physician with a splendid practice and a diplomat chosen by the administration to look out for its interests in the African country most identified with the negro race in the United States.”

After resigning from the post, the Evansville Courier reported that Dr. Buckner served as a member of a medical board that “examined Negro registrants during World War I.” He continued his work as an Evansville physician, working fulltime into his 80s. Buckner died in 1943 and was buried at Oak Hill Cemetery. The City of Evansville, which had at times been hostile to him, helped cement his legacy by dedicating a public housing project for the elderly in his name. The building was located at the former site of the Buckner family home. In 2022, his alma mater, Indiana State University, named him a Distinguished Alumni Honoree. He is remembered as an influential and accomplished Black man at a time when people of color were treated with overt discrimination. He told interviewer Lauana Creel “Yes, the road has been long. Memory brings me back to those days.” But, despite the hardships he faced throughout his life, Dr. Buckner cherished his freedom and maintained, “Why should not the negroes be exalted and happy?”

Sources:

Much of the information regarding Buckner’s life come from his interviews with Lauana Creel. It was through her work with the Federal Writer’s Project that firsthand accounts of Buckner’s life are available.

“George W. Buckner,” 1880 United States Federal Census, accessed Ancestry Library.

William Elmer Henry, Legislative and State Manual of Indiana for 1903 (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, State Printer, 1903), p. 324, accessed Internet Archive.

Louis Ludlow, “Indiana Negro Selected for Liberian Post,” Indianapolis Star, June 29, 1913, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Intends to Lash Capitalist and Labor Lobbies,” Indianapolis Star, September 17, 1913, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Receives Instructions: New United States Minister to Liberia,” Courier-Journal (Louisville, KY), September 20, 1913, 14, accessed Newspapers.com.

Courier-Journal (Louisville, KY), September 23, 1913, 12, accessed Newspapers.com.

“An Honor to the Colored People,” Evansville Courier and Press, October 10, 1913, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

“George W. Buckner, Minister Resident and Consul General to Liberia,” Altoona Tribune (Pennsylvania), January 2, 1914, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

“A Letter from Liberia,” Evansville Courier, June 6, 1914, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Will Liberia Survive?,” Tacoma Daily News (Washington), March 2, 1915, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

Louis Ludlow, “Negro Republic is Bumping the Rocks,” Fort Wayne News, March 5, 1915, 8, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Glad to See the Good Old U.S.,” Evansville Courier, June 6, 1915, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Dr. Buckner May Resign,” Indianapolis News, June 15, 1915, 8, accessed Newspapers.com.

“George Buckner Sr.,” 1920 United States Federal Census, accessed Ancestry Library.

Interview with George Buckner, conducted by Lauana Creel, Ex-Slave Stories, District #5, Vanderburgh County, “A Slave, Ambassador and City Doctor,” Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, vol. 5, Indiana, Arnold-Woodson, 1936-1938, Federal Writer’s Project, United States Works Projects Administration, accessed Library of Congress.

“George W. Buckner,” 1940 United States Federal Census, accessed Ancestry Library.

“Dr. G. W. Buckner, Former Minister to Liberia, Dies,” Evansville Press, February 18, 1943, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Dr. Buckner,” Evansville Press, February 19, 1943, 8, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Gifts to a Slave Turned Diplomat Given to Museum by His Son,” Evansville Press, May 10, 1965, 13, accessed Newspapers.com.

Kathie Meredith, “New Building for Elderly to Get Name of Slave-Born Envoy-Doctor,” Evansville Press, May 9, 1968, 29, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Dr. Buckner Gifts Shown at Museum,” Evansville Press, August 17, 1968, 12, accessed Newspapers.com.

Evansville Press, January 27, 1969, 11, accessed Newspapers.com.

Edna Folz, “Dr. Buckner, a Dynamic Revolutionary,” Evansville Press, February 14, 1972, 13, accessed Newspapers.com.

John W. Blassingame, The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South (Oxford University Press, 1979).

“Evansville Doctor Was a Democrat during Unpopular Era,” Evansville Press, June 5, 1987, 19, accessed Newspapers.com.

Darrel E. Bigham, We Ask Only a Fair Trial: A History of the Black Community of Evansville, Indiana (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), accessed Scholarworks.

“Dr. George Washington Buckner,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 31, 1990, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

Roberta Heiman, “An Evansville Ambassador,” Evansville Courier and Press, February 22, 1998, 46, accessed Newspapers.com.

Enrique Rivero, “Proportion of Black Physicians in U.S. Has Changed Little in 120 Years, UCLA Research Finds,” UCLA Newsroom, April 19, 2021, accessed UCLA Newsroom.