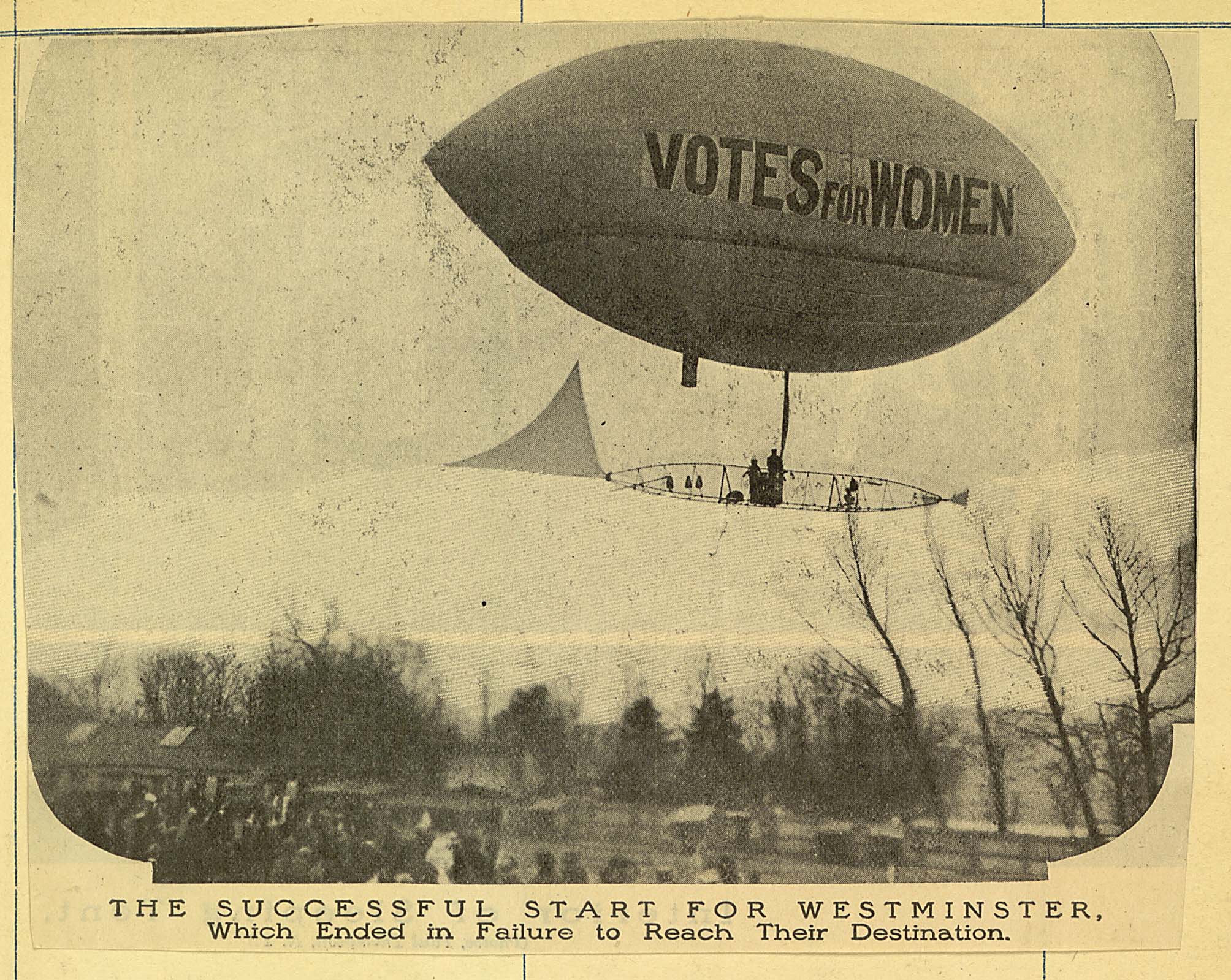

The Indiana woman’s suffrage movement was not a monolith. Its supporters held a spectrum of beliefs formed from their different backgrounds and perspectives. Nowhere was this more apparent than in rifts over strategy. Hoosier suffragists all believed women should have the vote, but clashed over the best course of action for winning it.

By 1912, Indiana’s organizations most assiduously acting in the political arena were the Woman’s Franchise League (WFL) and the Equal Suffrage Association (ESA). Both groups had strong leaders and experience with organizing, lobbying, and publicizing their views, meetings, and arguments for suffrage. Their work had recently become more urgent as Governor Thomas Marshall proposed a new, increasingly-restrictive state constitution that would further cement women’s disenfranchisement. They needed to influence the new 1913 Indiana General Assembly to create equal suffrage legislation before it was too late. They disagreed, however, on where to start. [1]

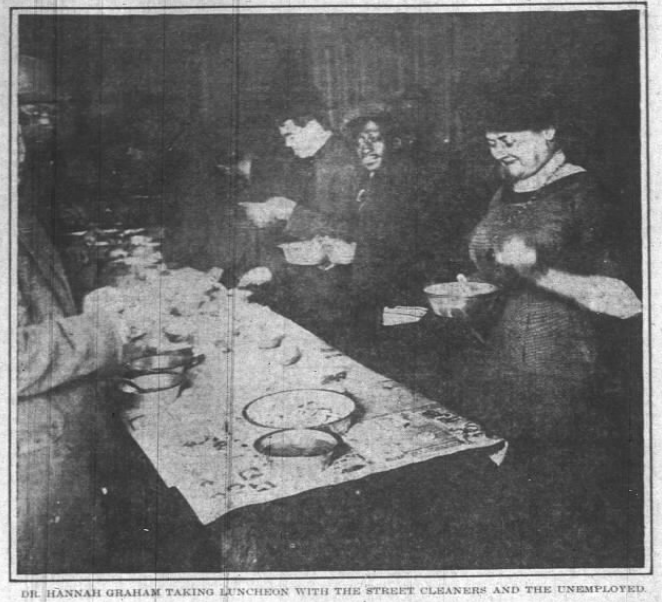

On the heels of its successful state convention in 1912 and success organizing new branches (including African American and labor branches), the ESA was well-positioned to unite the movement. Dr. Hannah Graham rallied ESA members behind the “Woman’s Declaration of Independence,” which called on women to break ties with any politician not willing to make a public declaration of their support for women’s suffrage. Suffrage took precedent over political alliances. [2]

The WFL also had a banner year in 1912. Prominent members traveled the state in automobile tours, handing out literature and reaching women in smaller towns. They organized high profile events that garnered press attention and signatures for suffrage petitions. And the WFL took on the important work of convincing women who were indifferent to suffrage that they could improve their everyday lives, their children’s schools, and the health of their communities with the vote. Despite the shared goals of the ESA and the WFL, they took opposing positions on a bill introduced by Indiana Senator Evan B. Stotsenberg in January 1913 that proposed granting women partial suffrage to vote in school board elections. [3]

The clash between the ESA and WFL over this bill embodied a major conflict within the larger suffrage movement. Should suffragists accept partial suffrage to get their foot in the door and later work for full suffrage or demand full suffrage as their inalienable democratic right? While both Indiana suffrage organizations had taken different stances on this issue previously, in January 1913, the ESA supported the partial suffrage bill, while the WFL opposed it as inadequate. [4] The debate between ESA and WFL leaders before the Senate committee on rights and privileges got . . . heated.

ESA leader Dr. Hannah Graham was an outspoken proponent of full suffrage, but put her ideological stance aside. She felt like Hoosier women couldn’t miss the opportunity that this bill afforded. According to the Indianapolis Star, ESA members voted to support the partial suffrage bill because “such franchise is as much as can be expected at this time.” [5] Simply put, a little suffrage was better than none and might help in garnering full suffrage down the road.

WFL leaders vehemently disagreed. Digne Miller noted first that the bill would only grant this partial suffrage to women in Indianapolis and Terre Haute – more a fractional suffrage bill than a partial one. Dr. Amelia Keller expressed her fear that the bill could actually hurt the larger movement. [6] Dr. Keller argued:

If that bill goes through it will be immediately sent into the courts on protest of being unconstitutional and then when the vote for full suffrage really comes we will receive our answer, ‘O that question is now in court. Wait until that is settled and we’ll see about it then.’ [7]

In fact, some WFL members thought that delaying the full suffrage vote was the senator’s reason for introducing the bill in the fist place. Sen. Stotsenberg had also introduced a full suffrage bill that would have had to pass two legislative sessions and then go to a statewide referendum, a process that would take years. So it was not entirely unreasonable to think that he wanted to kick the problem down the road. [8]

Even within the organizations, there was disagreement. Prominent league member Belle Tutewiler broke with her WFL colleagues to support the bill. Her argument in favor of partial suffrage was to use this limited franchise to pry open the door of full suffrage. Her valid point may have been overshadowed by her fiery language. She called the league’s opposition “childish” and stated:

It is mere child’s play to say that if we can not get all, we will take nothing. I think it would be better to take school suffrage now and use that as an entering wedge for full suffrage later. [9]

As discussion continued, the women’s language grew more contentious. In the midst of the discussion, Elizabeth Stanley of Liberty threw open a suitcase “scattering yards and yards of cards bearing a petition for full suffrage” and “ridiculed the idea of using school suffrage as a wedge.” [10] The women exchanged more heated words before the ineffective meeting was adjourned and the partial suffrage bill abandoned.

The Indianapolis Star clearly delighted in the drama. The newspaper devoted long articles to the debate, written in a patronizing tone. Front page headlines read:

Suffrage Hosts Scorn Offerings

Resentful Women in Public Meeting Condemn Bill to Give Vote on Schools

“Childish” Starts Storm

Accusation from Lone Defender of Measure Brings Heated Denial of “Imbecility” [11]

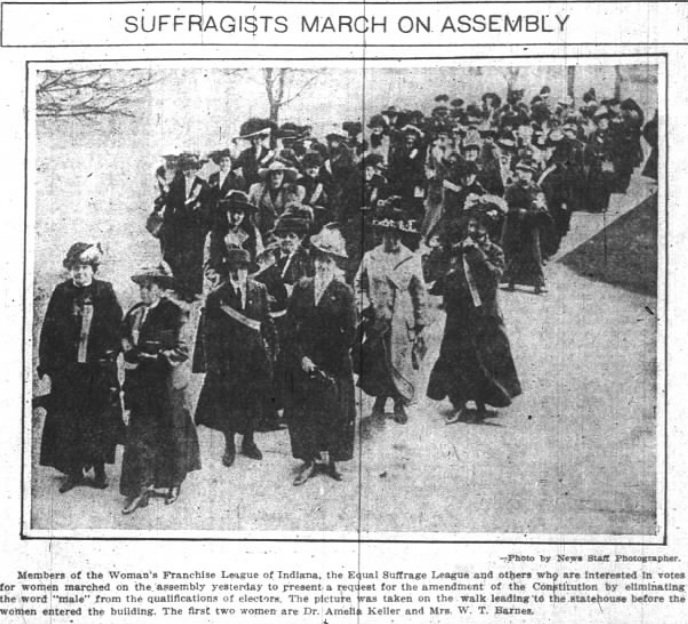

This public disharmony was not a good look and both organizations knew it. The WFL and the ESA were experienced publicists and aware that they needed a major public event to draw positive press coverage. The groups had to come together, if only briefly, and present a united front before the General Assembly. The WFL took the lead. The group organized a march to the Indiana statehouse for March 3, 1913, the same day 5,000 suffragists marched through the nation’s capital. [12] This was the perfect opportunity to present a united front and ESA leader Dr. Hannah Graham contacted the WFL asking to join forces. The WFL agreed. Just two months after their public disagreement over partial suffrage, the groups would march shoulder to shoulder before the Indiana General Assembly. [13]

It’s unclear if Black suffragists joined the march. African American ESA Branch #7 wouldn’t be organized until that summer. Newspapers catering to a white audience made no mention of their participation and the Indianapolis Recorder seemed to have been frustrated by the lack of Black suffrage information. A vexed Recorder writer, who went only by her first name of Dorothy, wrote on March 8:

What part did the colored women take in the suffrage movement at Washington last Monday? What part are they taking at any time? What are they, women or mice? Let us hear from you. Speak up! [14]

It is likely that Black suffragists at least knew about the march. The Woman’s Civic Club was an African American organization that worked to oppose race and gender discrimination in 1913. The Indianapolis branch had ninety-one members and promoted their events with the words of W. E. B. DuBois: “Protest, Reveal the truth and refuse to be silenced.” [15] The club had recently hosted Mary Tarkington Jameson at their regular meeting. Jameson was a prominent WFL member and spoke to the Woman’s Civic Club prior to departing for Washington D.C. to represent Indiana in the suffrage parade. The Recorder reported that Jameson delivered a “splendid address on Woman’s Suffrage” for the club. [16] It seems unlikely that Jameson would not have talked about current issues and upcoming events. Whether the Black suffragists in attendance would have been welcomed or felt safe in attending, would have been another matter. Unfortunately, this information is absent from sources.

On Monday afternoon, March 3, 1913, Hoosier suffragists from across the state, 500 strong, marched into the statehouse. [17] This was not a celebratory parade, nor was it a raucous demonstration. It was a protest. The suffrage bills being considered by the General Assembly were unlikely to pass “as the house of representatives was known to be unfriendly to equal suffrage,” and the Senate had already rejected at least one of the pending propositions earlier in the day. The suffragists were there not because they thought any “immediate good” would come from the day’s session. [18] Five hundred women marched into their capitol that day to make their presence known. They were there to “work on the legislature,” to show them that this was not a fringe movement, that a large number of Hoosier women demanded the vote. [19] WFL president Dr. Amelia Keller stated,

We wanted to show the legislators that we are in earnest and that ‘we’ means not a handful of enthusiasts, but hundreds of women. [20]

A pro-suffrage stance was edging towards the mainstream in 1913 but needed a push. It wasn’t a view that needed to be kept secret like it was when the Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society first met conspiratorially in 1878, but nor was it ubiquitous. [21] The more conservative members of the Indiana Federation of Clubs, for example, still had not endorsed suffrage at the time of the march, though they would later that year. [22] Suffrage in Indiana was at a tipping point and so they marched.

Several unlikely suffrage measures were before the Indiana General Assembly on the day of the march. Representative Earl K. Friend had introduced a resolution to amend the constitution, removing the word “male.” This resolution was pending in the House Judiciary Committee B, also known as the “graveyard committee” because it is where dead bills were buried. There was no hope for the suffragists there. The identical resolution introduced by Senator Harry E. Grube had already failed in the Senate that morning. [23]

The United Press wire service reported that several suffrage leaders had also been working with Rep. Friend on an amendment to the bill introduced by Rep. Stotsenburg, which also aimed to amend the constitution to remove the word “male.” Some of the women may have warily hoped that this proposal would gain support, but were not expecting any immediate results. Even if the bill passed, it had to be approved again at the next session in 1915, and then voted on in a statewide referendum in 1916 at the earliest. [24] Hoosier suffragists had lost this battle before, celebrating the passage of suffrage bills at one session, just to be disappointed at the next. [25] The women marching in the statehouse that day would not have had anything to celebrate, even if the bill passed, because they would have been made again to wait for equality. Their spirit would have been somber and determined, not hopeful. Their solemn march matched the moment.

The 500 Hoosier suffragists walked through the statehouse stopping to pin suffrage ribbons on a few willing lawmakers. Governor Samuel Ralston “cheerily” accepted a ribbon as did the legislators representing the Progressive Party, the only party to add a suffrage plank to their platform. [26] Most Indiana lawmakers did not take a ribbon, and pages mocked the women’s efforts. [27]

Indianapolis newspapers either misunderstood the suffragists’ goals or reporters intentionally decided to recast the scene through a condescending lens. The Indianapolis Star called their attempt to distribute ribbons to lawmakers “a game of hide and seek.” [28] The newspaper claimed that prominent writer and WFL leader Grace Julian Clarke “moaned in grief” because her husband, Senator Charles B. Clarke refused a ribbon. [29] The Indianapolis News was even more patronizing.

The News sarcastically described the suffragists as wearing “warpaint of fine feathers and pretty gowns” and commented on the group’s choice to walk up the stairs en masse instead of splitting up to take the elevators. [30] The News claimed that one woman stated that by taking the stairs they hoped “the men will see that we are not afraid of some of the hardships,” but that if they gained the vote “one of the first things that we will do will be to add more elevators to the statehouse.” [31] This quote is dubious in authenticity, and the jab was certainly patronizing, but all in all, a comparatively harmless aside. The rest of the News article, however, must have been infuriating to these politically savvy suffragists.

The Indianapolis News claimed that while the suffragists marched around the statehouse, they had no idea what legislation was pending, or that the suffrage amendments were being dismissed. The newspaper claimed that the suffragists were in the chambers when Sen. Grube introduced the resolution calling for the constitutional amendment but that “it was done so unobtrusively that the women did not seem to know that it had been done.”[32] And about the identical resolution introduced in the House by Rep. Friend, the writer scoffed:

The women had hardly been out of the state house more than an hour, however, when the house judiciary committee B voted in favor of killing the Friend house resolution . . . [33]

In case the newspaper’s readers missed this claim of female ignorance, the writer drove home the point:

Although hundreds of suffragists were jammed in the senate when Senator Grube introduced a resolution providing for an amendment to the state Constitution to allow women suffrage, not one of them seemed to realize what ‘was doing.’ No demonstrations of any sort took place. [34]

This claim is certainly false. First, these suffrage leaders were the most prominent women in the state. Indiana legislators were their friends, husbands, and family members. Second, the leaders of the WFL and ESA kept current on political issues related to suffrage at the state and national level. They wrote articles, gave speeches, organized meetings, and gathered signatures for petitions based on this knowledge. Most importantly, they had been working with members of the General Assembly on the legislation pending that day. The UP reported:

The leaders of the women planned to have Friend introduce a new resolution in the form of an amendment . . . [35]

They didn’t just know about the resolution, they were integral in its introduction to the legislature.

They knew the General Assembly would fail them that day. Their march was a protest, and this is why they chose silence. They came to make it clear to lawmakers that large numbers of the state’s most upstanding citizens were watching them. The General Assembly would have to face them before voting to continue to deny them their right as citizens. The UP reported that “dignity marked the demonstration,” as women representing “the best type of Indiana’s womanhood” gathered in the statehouse corridors.[36] They silently filed first into the House and then to the Senate. The UP reporter continued,

It was a silent demonstration. The leaders of the women attempted to make no speeches. They merely hoped that the number of mothers, wives and daughters, society leaders, professional women and working girls would cause the legislature to think about woman suffrage. [37]

The Indianapolis newspapers interpreted or framed their silence as ignorance, but it was the opposite. The suffragists knew that March 3, 1913 was not their day, but they made it clear that they would not stop their work until it was.

They did, in fact, achieve their goal in marching. The ESA and WFL presented a united front, countering the picture painted by their clash over partial versus full suffrage months earlier. All of the newspapers, even the condescending ones, that covered the march noted the joint appearance by the state’s major suffrage organizations. The UP reported that the event “was said to evidence the friendly relations between the two societies.”[38] Dr. Graham explained that this show of solidarity meant that “the legislators can no longer doubt the sincerity of the request of the women.” [39]

While Hoosier suffragists had a long road ahead of them, organized protests like this one, combined with lobbying, street meetings, sharp speeches, and savvy publicity stunts, helped to move public opinion and force lawmakers to give in to their demands. The press painted them at times as flighty, catty, or any other manner of stereotype, but their actions showed otherwise. While their methods sometimes produced discord between them, it was through the constant political work of these knowledgeable, experienced, calculating suffragists that they won for themselves the vote. As they marched on the statehouse, they chose silence, but through their numbers, dignity, and righteousness, they roared for the vote.

Notes and Sources

[1] Anita Morgan, We Must Be Fearless: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Indiana (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press, 2020), 101, 111.

[2] Ibid., 112-13, 117-18; Jill Weiss Simins, “‘Suffrage Up In The Air:’ The Equal Suffrage Association’s 1912 Publicity Campaign,” accessed Untold Indiana.

[3] Anita Morgan, “Taking It to the Streets: Hoosier Women’s Suffrage Automobile Tour,” accessed Untold Indiana. Prior to the discussion, Senator Stotsenberg withdrew his school suffrage bill and replaced it with a bill that would allow women to serve on school boards but not vote in the elections. Despite this change, the suffragists debated partial school suffrage versus full suffrage.

[4] Morgan, We Must Be Fearless, 118-19.

[5] “Bill Is Approved: Equal Suffrage Association Board Favors School Franchise Measure,” Indianapolis Star, January 25, 1913, 9, accessed Newspapers.com.

[6] “Suffrage Hosts Scorn Offering,” Indianapolis Star, January 25, 1913, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid. Stotsenberg’s full suffrage bill, even if it passed in 1913, would have had to pass again in 1915, and then go to a statewide referendum in 1916 or 1917.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “Women Divided on Ballot Bill,” Indianapolis Star, January 28, 1913, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

[11] “Suffrage Hosts Scorn Offering,” 1.

[12] “Woman’s Franchise League Will Go to Statehouse Monday and Ask Suffrage Amendment,” Indianapolis News, March 1, 1913, 11, accessed Newspapers.com.

[13] Morgan, 122.

[14] Dorothy, “Of Interest to All Women,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 8, 1913, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[15] “Woman’s Civic Club Notes,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 8, 1913, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[16] “Woman’s Civic Club Notes,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 1, 1913, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[17] “500 Suffragists Invade Capitol,” Indianapolis Star, March 4, 1913, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.

[18] “Indiana Women Work on the Legislature,” Huntington Herald, March 3, 1913, 1, accessed Newspapers.com. The Herald ran the article received from the United Press wire service.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “500 Suffragists Invade Capitol,” 3.

[21] Morgan, 62.

[22] Ibid., 95.

[23] “Indiana Women Work on the Legislature,” 1.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Morgan, 75. See Morgan for the political tricks that killed a suffrage bill in 1881 only to disappear from consideration in 1883.

[26] “500 Suffragists Invade Capitol,” 3.

[27] Ibid.

[28]Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] “Assembly Besieged by Nearly 500 Women,” Indianapolis News, March 4, 1913, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] “Indiana Women Work on the Legislature,” 1.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] “500 Suffragists Invade Capitol,” 3.