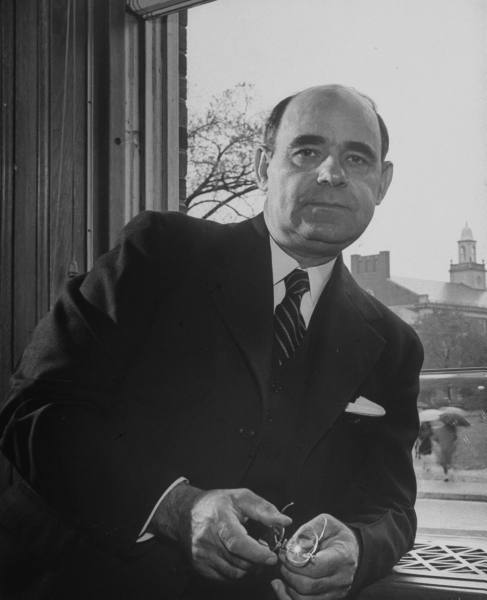

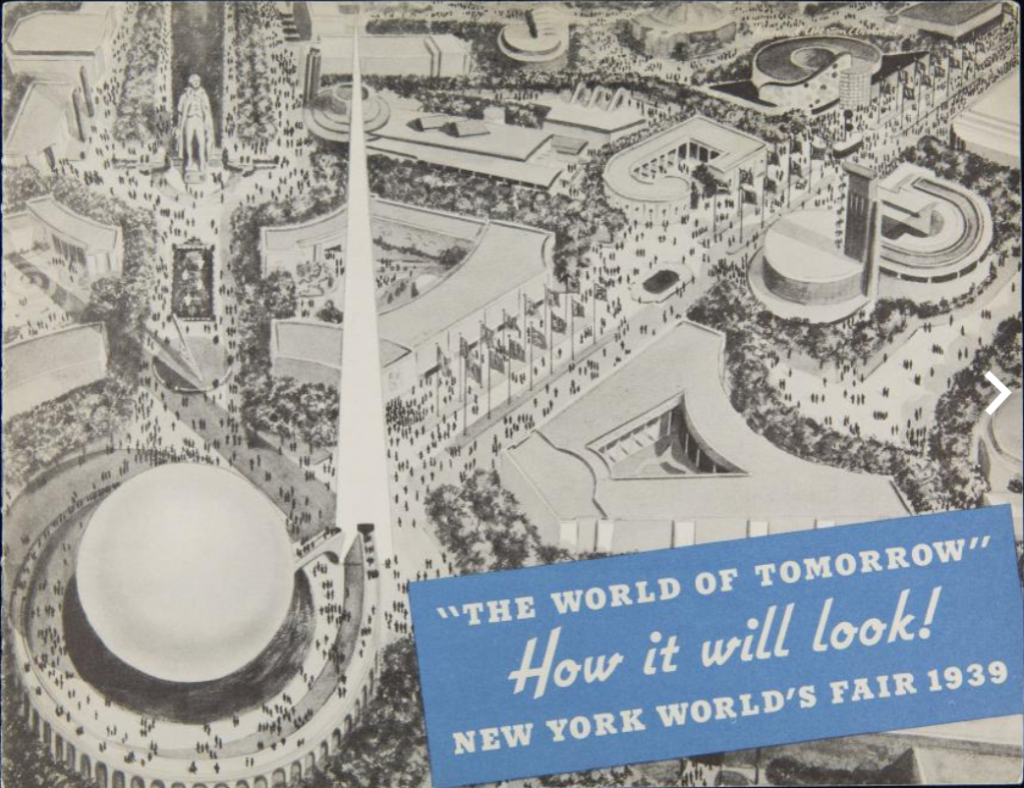

Visit the ultra-sleek website of the industrial design firm TEAGUE and you will see the echoes of company founder and namesake Walter Dorwin Teague. TEAGUE touts “we design experiences for people and things in motion.” This could easily have been declared in 1939 when Teague applied his experience as an industrial designer to the New York World’s Fair “World of Tomorrow.”

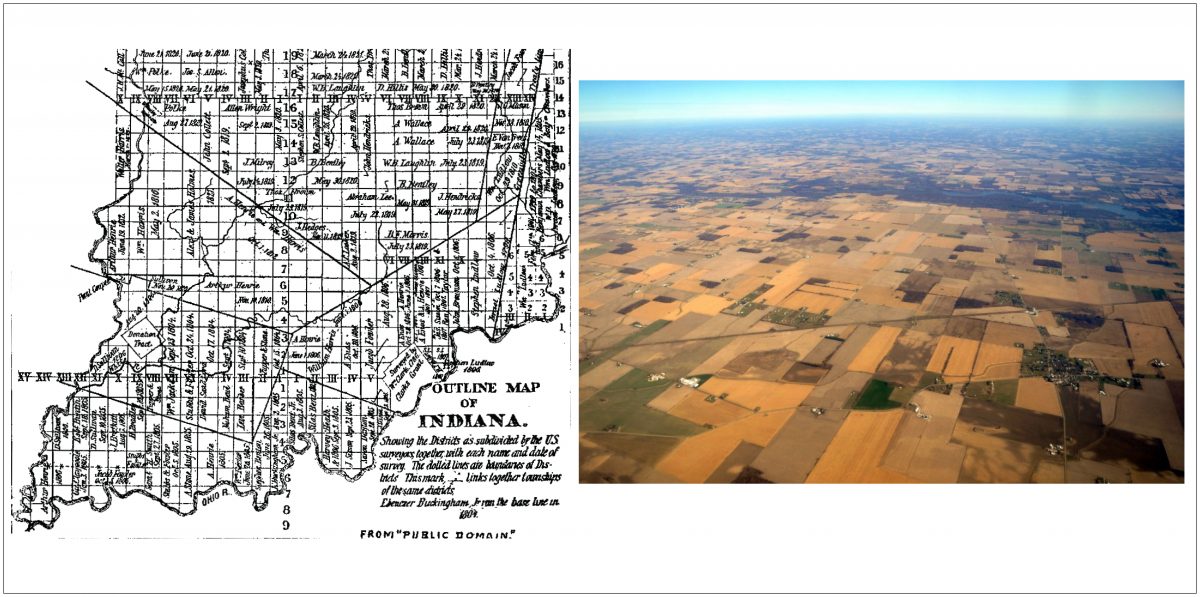

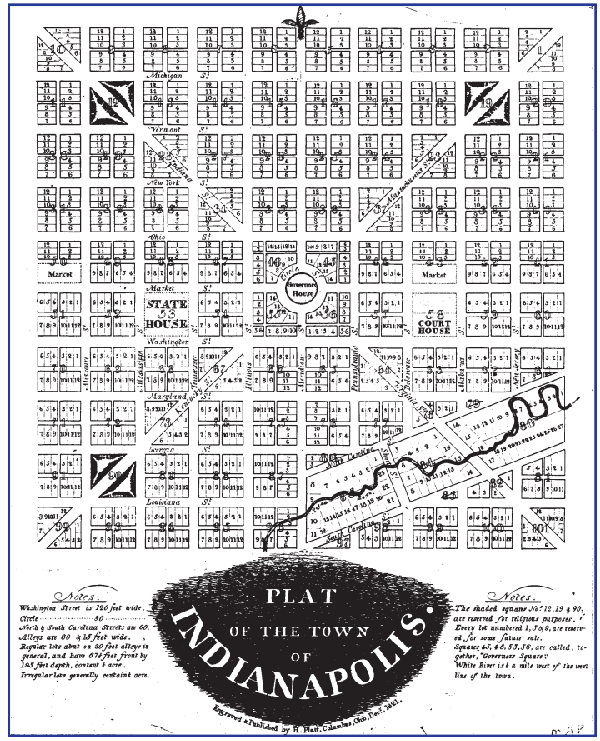

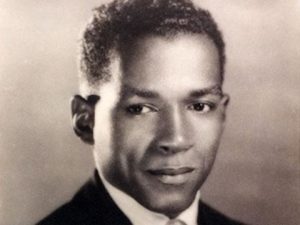

Walter Dorwin Teague’s story starts in the house of a Methodist circuit-riding preacher in Decatur, Indiana. Here, Walter was born on December 18, 1883, the youngest of six children to Reverend M.A. Teague and Hettie Teague. By late 1889, the family had settled in Pendleton, where Teague graduated high school in 1902. Teague credits his time in Pendleton, and particularly a book on the history of architecture from the Pendleton High School library, with setting him on the path that would eventually lead him to become a dominant force in American industrial design.

Soon after his graduation, Teague moved to New York City to study at The Art Students League of New York. However, it wasn’t until the late 1920s that Teague discovered his life’s passion: industrial design. He was early to the game – in the decade after Teague scored his first major contract with Eastman Kodak in 1928, mentions of the phrase “industrial designer” in printed material increased 40 fold. Many sources consider Walter Dorwin Teague to be one of the five founders of industrial design in the United States, along with Henry Dreyfuss, Donald Deskey, Raymond Loewy, and Norman Bel Geddes.

In the decade after his first contract with Kodak, Teague designed for the likes of Boeing, Texaco, the Marmon Motor Company, and Ford Motor Company. He built lasting business relationships with many of these companies, and in some cases those relationships went beyond the designing of products. In the early 1930s, Henry Ford turned to Walter Dorwin Teague to design a cutting-edge exhibit hall for the 1934 re-opening of the Chicago World’s Fair, themed “Century of Progress.” The exhibition featured a wide array of elements, including a museum, industrial barn, and gardens tied together by–what else–design.

According to historian Roland Marchand, the 1934 Chicago Century of Progress:

ushered in a period of striking convergence between an increasing corporate sensitivity to public relations and the applications of designers’ expertise to display strategies. More than ever before, the great fairs became arenas for the public dramatization of corporate identities.

Gone were the sales-driven exhibits of the past, in which company representatives pitched the latest and greatest Ford products. With Teague at the helm, salesmen were replaced by young, affable college students. Product demonstrations were replaced by art, dioramas, and museums. Pressure to buy was replaced with entertainment, as well as information about the concepts behind and benefits of featured products. These innovations made the exhibit a hit of the fair and Walter Dorwin Teague a highly sought after exhibition hall designer.

In the wake of the successful Ford project, Teague designed exhibits for a number of regional fairs. He designed for Ford in San Diego (1935), Dallas (1936) and Cleveland (1936), and for Du Pont and Texaco in Dallas (1936). These smaller exhibits were a trial of sorts for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, which would become Teague’s crowning achievement in the realm of exhibit design.

For the New York World’s Fair, which was themed “The World of Tomorrow,” Teague designed the exhibition halls for heavy-hitters like Ford, U.S. Steel, Du Pont, National Cash Register (NCR), Consolidated Edison Company, Eastman Kodak, A.B. Dick, Bryany Heater Company, and parts of the United States Government Building. In addition, Teague served on the official Design Board, the lone industrial designer among a group of architects.

One might assume that with so much on his plate, Teague would have moved towards a more hands-off approach at the 1939 fair. However, he was deeply involved in the conceptualization process. While on previous projects he had simply put the finishing touches on an already developed idea or perhaps added design elements around an existing exhibit plan, by 1939, Teague was involved in “the fundamental work of determining what [the] exhibit should be.” Employing lessons learned at the 1934 Century of Progress, Teague determined that exhibits should include animation and audience participation whenever possible. He and his team also began using phrases such as “visual dramatization” and “industrial showmanship” to describe their work. The resulting 1939 New York World’s Fair exhibits reflected the evolution of his design approach.

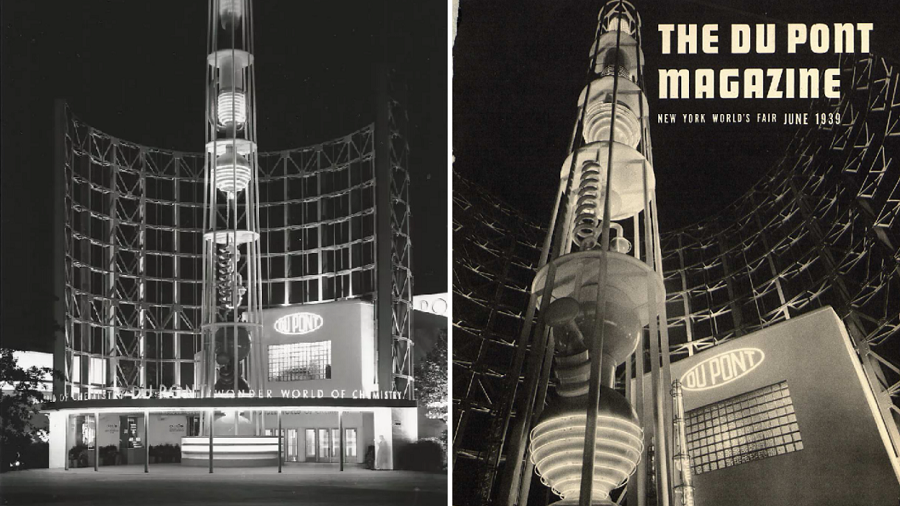

Du Pont, the company responsible for developments such as Kevlar, Teflon, neoprene, and Freon, had high expectations for their exhibit. In the November 1938 issue of The Du Pont Magazine, the company promised, “a panorama of man’s triumphs over his environment, of the progress he has made in building a new nation and a new civilization, of the hopes and plans he has for creating a better world in the future” and to illustrate “chemistry’s part in making the United States more self-sufficient.”

The resulting exhibition building, featuring a 120-foot “Tower of Research” inspired by test tubes, literally towered over passersby. The essential element of animation was incorporated through lights and bubbles that flowed through the test tubes and brought the structure to life. Inside the building were a variety of displays that highlighted the role of chemistry in the modern world–and painted a picture of what the “World of Tomorrow” could look like with further investments in the sciences. Displays followed the production process from raw materials to laboratory testing, and finally to manufacturing. Still other exhibits featured technicians weaving rayon, making cellophane, and demonstrating various techniques used in producing Du Pont materials. From the Tower of Research to fully functional displays to a plethora of dioramas, every aspect of Teague’s design employed the tenets of visual dramatization, industrial showmanship, and educational entertainment.

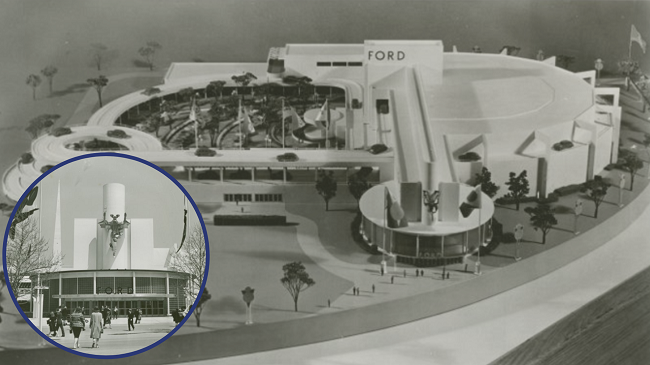

The same tenets were present in Teague’s development of the Ford building. Whereas a tower drew visitor’s eyes towards the Du Pont building, a metallic sculpture of the Roman god Mercury–symbolizing “fleet, effortless travel”–attracted exhibit-goers. Inside the exhibition hall, a 70-foot-high moving mural made of automobile parts, planned by Teague and designed by Henry Billings, welcomed visitors to the Ford building. The theme, “From Earth to Ford V-8,” was depicted in the “Cycle of Production,” a massive revolving wedding cake-like structure with three tiers. On the bottom tier, small animated figures harvested raw materials such as cotton, wool, and wood. On the next tier, figures processed those raw materials into cloth and boards. Finally, on the top tier, those products were incorporated into the final product – the wildly popular 1939 Ford V-8, a finished version of which adorned the top of the turntable. Surrounding the “Cycle of Production” were live demonstrations of the production process depicted in the display.

Even more so than in the Du Pont exhibition, Teague incorporated a plethora of entertainment elements into the Ford pavilion. The same figures from the Cycle of Production were featured in a Technicolor film, telling the story of Ford production. Visitors watched the history of transportation unfold in the form of a live musical drama and ballet. They also watched race car drivers demonstrating the abilities of Ford cars on an outdoor track. Teague united these seemingly disparate parts through design to tell the story of Ford’s impact on the world–whether that be in job creation, technological advancement, or simply as an amusing diversion.

The features seen in these two exhibition buildings could be found to varying degrees in Teague’s other designs at the fair. The U.S. Steel building consisted of a 66-foot-high stainless steel hemisphere, an early example of a building designed to highlight, rather than mask, its steel structural supports. The National Cash Register exhibit was perhaps the least innovative, yet most striking of Teague’s 1939 World’s Fair designs–it was simply a gigantic, working cash register which displayed the fair attendance numbers. Inside, various models of NCR registers were shown being used in exotic locals around the world. For Consolidated Edison’s “The City of Light” display, Teague recreated New York City by building 4,000 scale buildings. The diorama came to life to depict a day in the city–the printing press of the Brooklyn Eagle whirred, a family lounged on a porch listening to the radio, and a six-car subway sped through the display. These innovative features developed by the industrious Hoosier and his design firm would be the central design elements in exhibition halls for decades to come.

Walter Dorwin Teague is best remembered as the “Dean of Industrial Design.” His impact on corporate exhibitions has largely been forgotten with the diminishing role of exhibits in modern life. But at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, the impact of this industrious Hoosier was impossible to ignore.