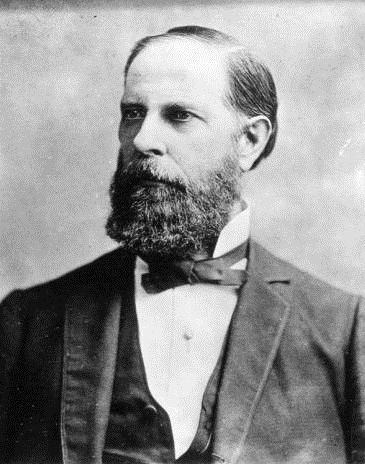

When I started researching him, William Hayden English seemed like a pretty typical figure for the 19th century: Congressman, businessman, Vice-Presidential candidate. However, I soon realized how complicated his life and his politics really were.

English played a key role in the unrest in Kansas during the antebellum period, yet supported the Union during the Civil War (but was still antagonistic towards Lincoln’s presidency). A deal broker, English often chose the middle of the road. He was a conciliator, a compromiser, and a tactical politician who was a Pro-Union Democrat who held misgivings about both slave-sympathizers in the South and radical Republicans in the North. In more ways than one, he was truly a man apart.

William Hayden English was born on August 27, 1822. Early in his life, English received some formal education. According to a letter by E. D. McMaster from 1839, English received education in the “Preparatory and Scientific departments” of Hanover College. Additionally, he received accreditation to teach multiple subjects at common schools by examiners Samuel Rankin and John Addison. He would eventually leave school and pursue law, where he passed the bar in 1840.

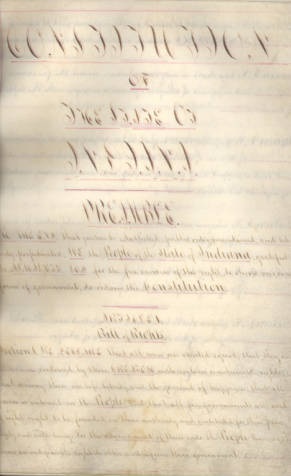

His major break in politics came with his selection as the principal Secretary of the Indiana Constitutional Convention of 1850. During his time as Secretary, he earned the reputation as being a thoughtful and balanced tactician, someone who was willing to work with others and make things happen.

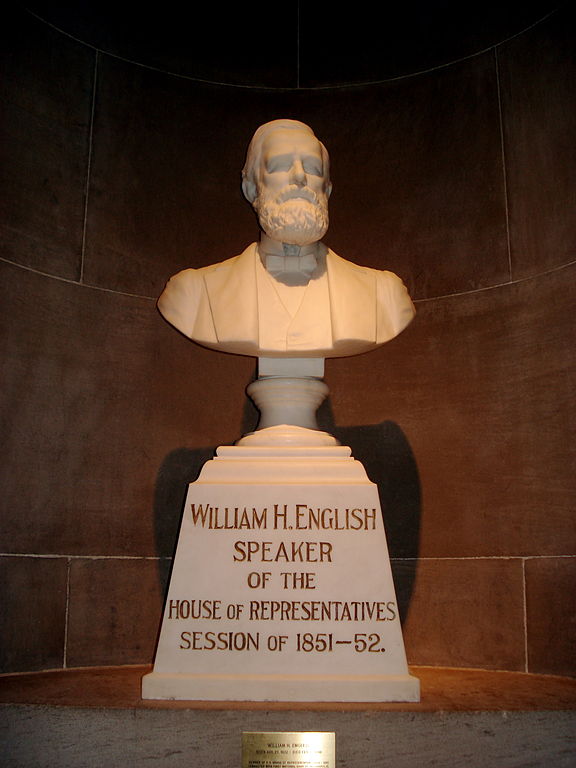

Using this newly-earned reputation, English was first elected to the Indiana House of Representatives from Scott County in August of 1851. On March 8, 1852, after the resignation of Speaker John Wesley Davis, English was elected Speaker of the House with an overwhelming majority of the vote. He was only 29 years old, making him the one of the youngest Speakers in Indiana History.

In his election speech, he stated his praise for the new Constitution and called for a full new legal code to be established. He additionally called for a “spirit of concession and compromise” and for his colleagues to “zealously apply himself to the completion of the great work intrusted [sic] to us by a generous constituency.” In effect, the Indiana House of Representatives under Speaker English had consolidated state government and extended its purview to neglected regions of the state.

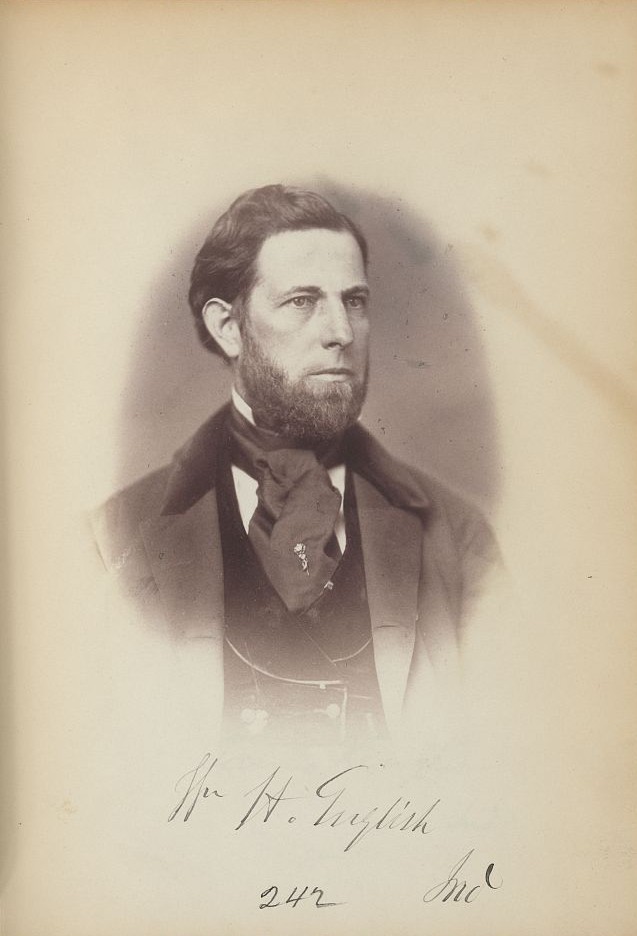

After his time in state government, English was called for national service. He won his first election to the United States House of Representatives in 1852, and was reelected in 1854, 1856, and 1858. During his tenure in Congress, English would be remembered for his “wise and patriotic course in Congress,” notably his important role in crafting a controversial bill that gave Kansas the choice of whether to come into the Union as a free or slave state.

English’s time in Congress, much like the rest of his political career, can be seen as pragmatic. While he morally abhorred slavery, he condemned abolitionists and believed in the notion of “popular sovereignty,” which argued that the people of a state or territory should choose for themselves whether to have slavery. He stated his view in a speech in 1854:

Sir, I am a native of a free State [sic], and have no love for the institution of slavery. Aside from the moral question involved, I regard it as an injury to the State where it exists….But sir, I never can forget that we are a confederacy of States, possessing equal rights, under our glorious Constitution. That if the people of Kentucky believe the institution of slavery would be conducive to their happiness, they have the same right to establish and maintain that we of Indiana have to reject it; and this doctrine is just as applicable to States hereafter to be admitted as to those already in the Union.

During this session, Congress was debating a bill named the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which would repeal the Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) and allow for states and their citizens to decide whether they wanted to be admitted as a slave state or free state. English voted for the bill and it was later signed into law by President Franklin Pierce on May 30, 1854. Almost immediately, violence erupted between pro-slavery and anti-slavery advocates in the state, who could not agree on the direction of the state constitution.

After his reelection in 1856, English, along with congressional colleague Alexander Stephens, went to work on a compromise bill that would potentially quell the violence and political unrest. This compromise, known as the English Bill, allowed the citizens of Kansas to either accept or reject the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution. However, if the citizens of Kansas chose to be a slave state by referendum, they had to additionally let go of federal land grants within the territory.

The bill passed and the voters of Kansas did not reject the land grants, thus rejecting the Lecompton Constitution. Upon the Bill’s passage, English declared that, “The measure just passed ought to secure peace, and restore harmony among the different sections of the confederacy.” The Kansas issue would be not resolved until its admission to the Union as a free state in 1861. As he did in the Indiana House, English struck a compromise that hoped to quell the violence, using federal land grants as a way to take heat off the slavery issue.

While the English Bill attempted to stave off conflict within Kansas, the harmony among the nation was short lived. The growing tensions among pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions of the country were mounting, and English lamented this development in one of his final speeches to Congress. He chastised both the abolitionists and radical Republicans, who he believed had appealed to the “passions and prejudices of the northern people, for the sake of getting into office and accomplishing mere party ends.” To English, the cause of all this strife was the agitation of the slavery question and the solution would be to elect a Democrat President and ensure that the national discussion be reverted back to other issues of state. This did not happen; in the fall of 1860, voters chose Republican Abraham Lincoln and the first seven southern states seceded from the union.

By 1861, right as English was leaving Congress, the United States became engulfed in Civil War. While many within the national Democratic Party either defected to the Confederacy or took a tenuous position of support in the north, English was unequivocally for the Union. In an August 16, 1864 article in the Indiana Daily State Sentinel, the Committee of the Second Congressional District, under the chairmanship of English, wrote a platform that supported the Union and decried the act of secession. However, it did reserve criticism for President Lincoln, particularly with regards to supposed violations of freedom of speech. English’s pragmatic, even-handed political gesture fell in line with many of his past political actions.

After his time in Congress, he was the President of the First National Bank of Indianapolis for 14 years. He established the bank in 1863, taking advantage of the reestablished national banking system during the Civil War. According to historian Emma Lou Thornbrough, the First National Bank of Indianapolis became “the largest bank of Indianapolis, and one of the largest in the Middle West.” He is also listed as a “banker” in the 1870 Census and as a “capitalist” in the 1880 Census. By the time of his death in 1896, English had become one of the wealthiest men in Indiana.

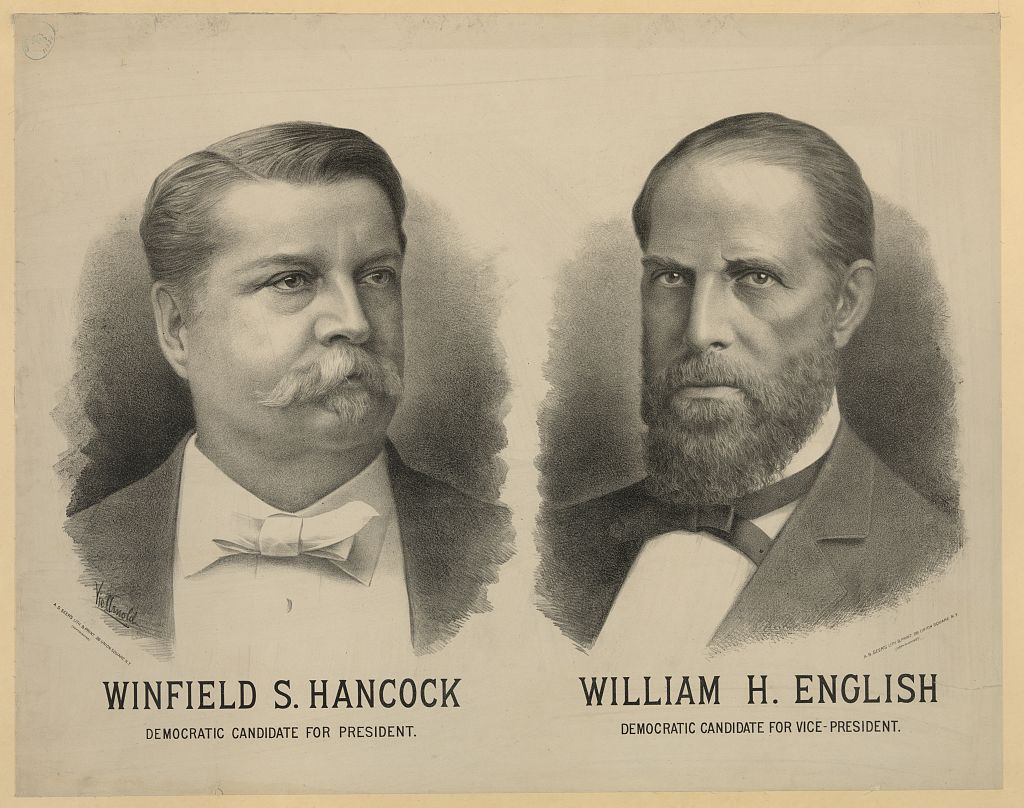

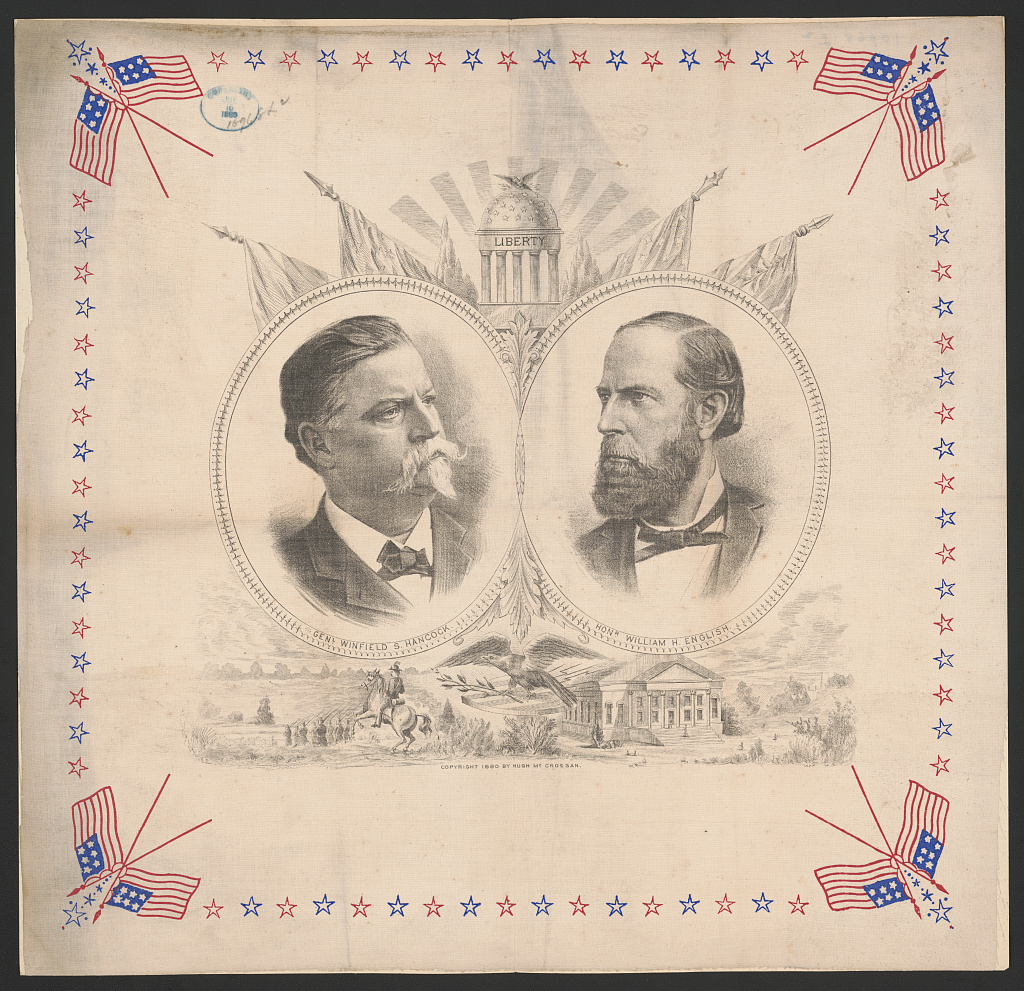

Even though his time in national politics was years removed, he was nonetheless nominated by the Democratic Party in 1880 for Vice President, with Winfield Scott Hancock as President. Articles in the Indianapolis News and the Atlantic noted that his chances for the Vice-Presidential nomination were quite good, especially if the candidate was presumed front-runner Samuel J. Tilden of New York. Within days of the News piece, when asked if he was interested in the VP nomination, English said, “None whatever, for that or any other office.

Despite his protestations, English was nominated for the Vice-Presidency by the Democratic Party on June 24, 1880, after Tilden redrew his consideration for the Presidential nomination and General Winfield Scott Hancock was elected in his stead. In his acceptance letter, English wrote that he was “profoundly grateful for the honor conferred” and that his election with Hancock would be a triumph over the dominance of the Republican Party in the presidency. Their chances to win the White House were dashed when they lost to Republicans James Garfield and Chester Arthur in the General Election.

While he was running for Vice-President, English’s business empire was also expanding, with his financing and construction of the English Hotel and Opera House. Historians James Fisher and Clifton Phillips noted that English purchased land on the city circle in the 1840s, as a residence for himself and his family. In early 1880, during renovations on the circle, English announced that he would invest in the construction of a new Hotel and Opera House. His son, William E. English, became the proprietor and manager. It officially opened on September 27, 1880, and the first performance was Lawrence Barrett as Hamlet. It would be in continual use until its closure and demolition in 1948.

English served as the President of the Indiana Historical Society, from 1886 until in his death ten years later. During his tenure, English wrote a two-volume history of the Northwest Territory and the life of George Rogers Clark. It was published in 1896, shortly after his death. An 1889 article in the Indianapolis Journal noted his compiling of sources and his emerging methodology; a two-volume general history that would be divided at the 1851 revised State Constitution. By 1895, the project materialized into the history mentioned above, with English using documents from leaders involved, such as Thomas Jefferson and Clark himself. He also conducted interviews with other key figures of the revised Indiana Constitution. English’s historical research became the standard account of the Northwest Territory for those within the Historical Society and the general public for many years.

William English died on February 7, 1896, as reported by the Indianapolis Journal. On February 9, thousands came to see his body displayed in the Indiana State Capitol before he was buried in Crown Hill Cemetery.

His legacy in Indiana is lesser known, but he does have some monuments. A sculpture in the Indiana Statehouse commemorates his place in history. The town of English, Indiana is also named after the late politician. According to historian H. H. Pleasant and the Crawford County Democrat, the unincorporated town was originally named Hartford. It was changed to English in 1886 after the town was officially incorporated, in honor of election to Congress from the area. He also has an IHB marker at his former home in Lexington, Scott County, Indiana.

To many who enter the Statehouse and see his statue on the fourth floor, he might be just another leader of Indiana’s past. However, English’s political career attempted to stave off Civil War (at least temporarily) and reinforced Indiana’s political tradition of measured, temperate leaders who sought a middle ground on most issues. In that regard, English might be one of Indiana’s most emblematic statesmen.

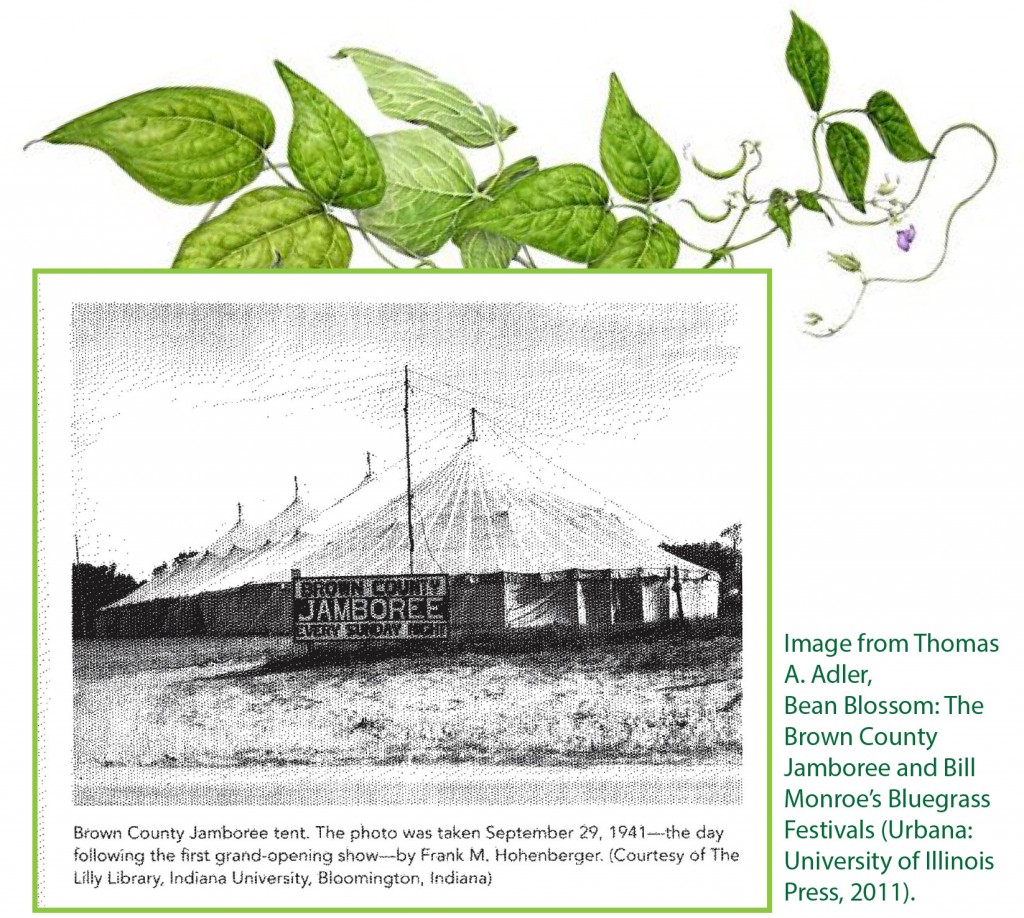

The “free” aspect of the free show didn’t last long, as the organizers couldn’t help but see how the crowd was growing. The lunchroom business was booming and there was no reason the promoters and performers shouldn’t make a little money too. They built a small stage, fenced in the area, and started to charge twenty five cents per show. Soon, they put up a tent as can be seen in the only known photograph of the Jamboree from this period.

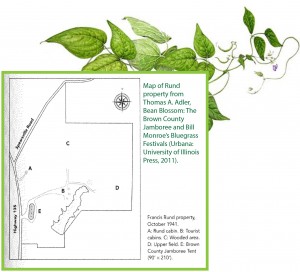

The “free” aspect of the free show didn’t last long, as the organizers couldn’t help but see how the crowd was growing. The lunchroom business was booming and there was no reason the promoters and performers shouldn’t make a little money too. They built a small stage, fenced in the area, and started to charge twenty five cents per show. Soon, they put up a tent as can be seen in the only known photograph of the Jamboree from this period. Just before the Jamboree launched, locals Francis and Mae Rund had been making improvements to their nearby property and building cabins with some sort of tourism-related business in mind as early as August 1940. By the summer of 1941, as the large crowds coming to the Jamboree were causing traffic and parking problems and more seating was needed at the outdoor venue, the Runds saw an opportunity to construct a permanent building (as opposed to a tent) so the programs could continue be held in the winter. Construction began in October. The barn-like building was funded by residents and was to seat 2,500 attendees. On October 23, 1941, the Brown County Democrat reported:

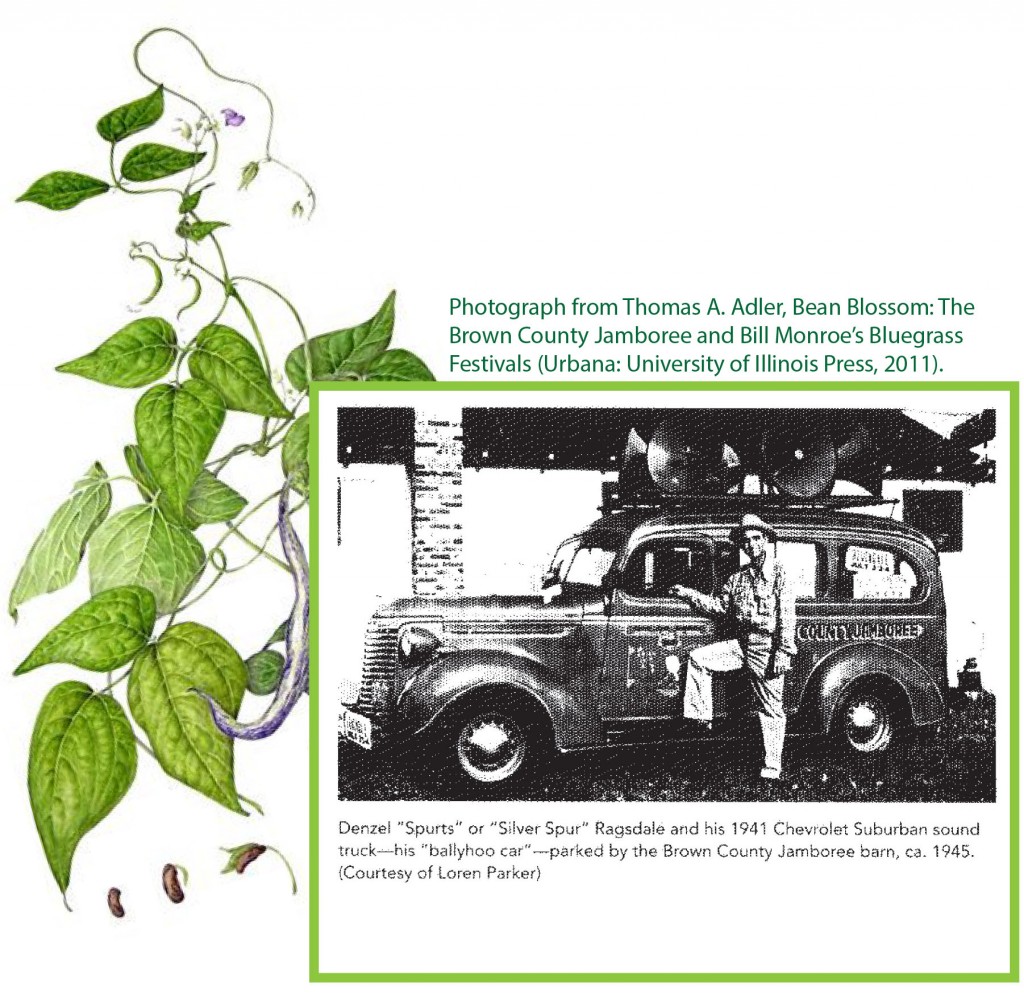

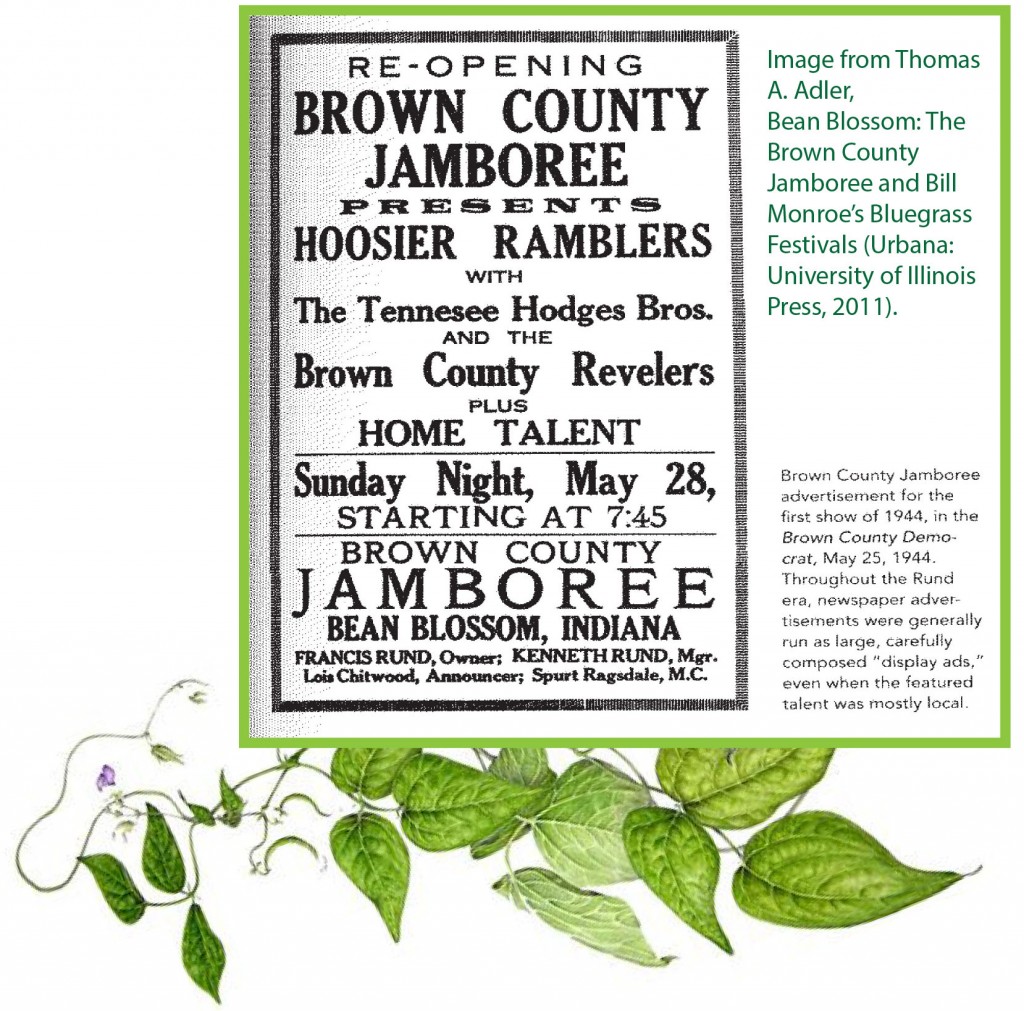

Just before the Jamboree launched, locals Francis and Mae Rund had been making improvements to their nearby property and building cabins with some sort of tourism-related business in mind as early as August 1940. By the summer of 1941, as the large crowds coming to the Jamboree were causing traffic and parking problems and more seating was needed at the outdoor venue, the Runds saw an opportunity to construct a permanent building (as opposed to a tent) so the programs could continue be held in the winter. Construction began in October. The barn-like building was funded by residents and was to seat 2,500 attendees. On October 23, 1941, the Brown County Democrat reported: The shows during the Rund decade (1941-51) generally featured a variety show format hosted by an emcee which included comedic performers as well as music. However, the country and “hillbilly” music was always the main draw. Adler writes, “Brown County Jamboree shows were professional, fast paced, and entertaining. From the beginning, the music, comedy, and ambience of the site combined to present a nostalgic and entertaining whole.” The Indianapolis Star on August 10, 1941 described the Jamboree as “a co-operative program providing real, homespun talent, rail-fence variety of music and frivolity . . . old fiddlers and rural crooners, who would sing and warble Brown county ballads brought over the mountains by their pioneer ancestors.” The Indianapolis Times noted October 10, 1941 that in addition to “singing and dancing” the Jamboree included “vaudeville skits.” The Runds ran large advertisements for the Jamboree in the local newspaper and partnered with nearby radio stations, notably WIRE and WFBM, Indianapolis. On October 23, 1941, the Brown County Democrat reported that the Indianapolis radio station WIRE referenced the Jamboree many times during its programs.

The shows during the Rund decade (1941-51) generally featured a variety show format hosted by an emcee which included comedic performers as well as music. However, the country and “hillbilly” music was always the main draw. Adler writes, “Brown County Jamboree shows were professional, fast paced, and entertaining. From the beginning, the music, comedy, and ambience of the site combined to present a nostalgic and entertaining whole.” The Indianapolis Star on August 10, 1941 described the Jamboree as “a co-operative program providing real, homespun talent, rail-fence variety of music and frivolity . . . old fiddlers and rural crooners, who would sing and warble Brown county ballads brought over the mountains by their pioneer ancestors.” The Indianapolis Times noted October 10, 1941 that in addition to “singing and dancing” the Jamboree included “vaudeville skits.” The Runds ran large advertisements for the Jamboree in the local newspaper and partnered with nearby radio stations, notably WIRE and WFBM, Indianapolis. On October 23, 1941, the Brown County Democrat reported that the Indianapolis radio station WIRE referenced the Jamboree many times during its programs.