On April 19, 2018, over a chain link fence Hammond resident and former EPA attorney David Dabertin voiced his concerns about the former site of Federated Metals to Governor Eric Holcomb. East Chicago environmental activist Thomas Frank told Mother Jones weeks after the visit “’We’d known for quite some time that there was some contamination there,’” but the Indiana Department of Environmental Management allowed plants at the site to keep polluting. For decades, industry was the region’s bread and butter and often the corporation’s and community’s financial well-being was prioritized over health or environmental concerns. Frank noted that older generations viewed the plants with “a sense of pride as it provided jobs and stability” and do not “‘want to look at what they’re so proud of and see that it’s harming them.'”

The EPA’s 2018 investigation of Hammond’s soil lead levels, a response to the “national criticism of its slow reaction to polluted water in Flint, Mich., and lead-contaminated housing in East Chicago,” (Chicago Tribune) inspired us to take a look at Federated Metal’s origins. In 1937, the Chicago-based company announced it would establish a plant in the Whiting-Hammond area. By 1939, hundreds of workers produced non-ferrous metals used in automobile, housing, and oil drilling industries. Almost immediately after production began, the community voiced complaints about the effects on their health.

In the spring, a citizens committee decried the fumes and smoke being expelled by the new smelting and refining plant—so noxious that students at St. Adalbert Catholic parochial school had to miss class due to illness—and pressed city officials to intervene. That year, resident Frank Rydzewski wrote to the Munster Times that Federated Metals foisted upon the Hammond community a “generous sample of sickening odors which emit from its midget—partially concealed smoke stacks and which have already showed its ill-effects on pupils of a school situated not a block distant.”

Rydzewski’s next sentiment encompassed the conflicting priorities related to Federated Metals from the 1930s until its closing in 1983: “Certainly, the value of health impairment to residents in the vicinity far surpasses any questionable tax-able asset this company can create.” Although he bemoaned the fumes plaguing the city’s residents, he also noted that the plant could “boast of its colored personnel; its predominating out-of-state and outside employe[e]s; its labor policies.” Since the 1930s, Federated Metals has served as both the bane and pride of Hammond and Whiting residents. The plant experienced labor strikes, symbolized livelihood and industrial progress, helped the Allies win World War II, and was the site of accidental loss of life.

In April, the Munster Times reported that hundreds of residents in the area “revolted” against the plant’s operations at the city council meeting. They charged that “harmful gas discharges from the plant damaged roofs of residences, caused coughing and sneezing that punctuated school studies and prayers in the Whiting church and school and made it virtually impossible to open doors or windows of homes in the neighborhood.”

The paper noted that Mrs. Feliz Niziolkeiwicz wept as she addressed plant manager Max Robbins. She told him “You can live in my home for free rent if you think you can stand the smoke nuisance. The home I built for $10,000 is almost wasted because of the acid from the plant.” Her concerns were shared by Hammond Mayor Frank R. Martin, the city council, the city board of public works and safety, and the health department, whose secretary ordered Federated Metals one month prior to “abate the nuisance” within sixty days. In October, the company was tried in a Hammond city court hearing and found not guilty of criminal liability for the fumes, despite city health inspector Robert Prior testifying that Federated Metals “continued to operate and discharge gasses on the Whiting-Robertsdale community after repeated warnings to abate the alleged nuisance.”

By November, Federated Metals had constructed a $50,000 smoke stack much taller than the previous, offending one, so as to diffuse smoke farther above the Robertsdale neighborhood. In March 1940, Prior stated that citizen protests had ceased with the improvement. Following this remediation, the Munster Times published a smattering of articles throughout the 1940s about health complaints related to plant output. In October 1941, the Times published a short, but eyebrow-raising article regarding allegations that Federated Metals tried to pay Whiting residents in the area as a settlement for property damaged by fumes. Councilman Stanley Shebish shouted “When the people of this community suffer bad health and many can’t go to sleep at night because of this smoke and particles of waste, it is time to stop an underhanded thing like this!” Health officials maintained that the sulphur dioxide fumes were “not a menace to health,” but may be “detrimental to flowers and shrubs.” Whiting’s St. Adalbert’s Church filed a similar complaint about the health of students, teachers, and parishioners in 1944.

While citizens lamented pollutants, the plant churned out “vital war materials” for World War II operations. (The Air Force also awarded the company contracts in the 1950s.) In accordance with the national post-war trend, 1946 ushered in labor strikes at the Hammond-Whiting plant. The Times reported that in January CIO United Steelworkers of America closed down the “Calumet Region’s steel and metal plants,” like Inland Steel Co., Pullman-Stan. Car & Mfg. Co., and Federated Metals. On February 17, Federated Metals agreed to increase the wages of its 350 employees to $32 per month. Labor strikes, such as that which “deprived workers of a living and dampened Calumet Region business,” took place at Federated Metals until at least 1978. This last strike lasted nearly five months and required the service of a federal mediator.

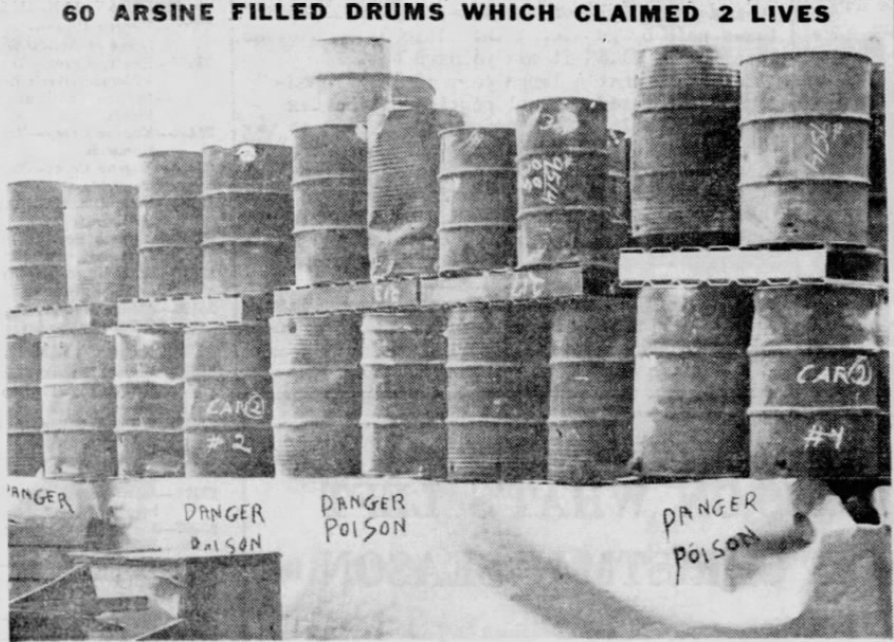

On January 5, 1949, one of the grimmest events in the plant’s history took place at the receiving department. While unloading a shipment from National Lead Co., Federated workers were suddenly overcome by arsenic seeping from rain-sodden drums. The gas, which can also cause paralysis, memory loss, and kidney damage, took the lives of four men and hospitalized eleven. The Times noted that “only the caprice of weather saved scores of Hammond and Whiting residents” from dying while the open freight cars transported the drums from Granite City, Illinois to the Federated Metals plant. The cities’ residents narrowly avoided catastrophe, since rain causes metal dross to generate deadly arsine gas.

Dr. Richard H. Callahan, East Chicago deputy coroner, probed the deaths and placed the blame primarily on the state board of health. He lamented “‘It is inconceivable that the chemists in the state board did not know that dross used by Federated Metals would poison workmen with arsine. Federated Metals was in the possession of a dangerous toy.” He noted that safeguards against arsenic poisoning had existed for thirty years, ranging from gas masks to the use of caged birds, who fell ill at lower concentrations of gas than humans. The Times noted that Dr. Callahan’s investigation was expected to “foster national and international safeguards against arsine poisoning.”

A.J. Kott wrote in the paper that Federated workers’ lives could have been saved had British Anti-Lewisite (BAL) been on hand, “a miracle drug, discovered during World War I in University of Chicago laboratories.” Instead, the drug had to be rushed to St. Catherine Hospital to treat affected workers. While Dr. Callahan identified the state board as the responsible party, questions regarding Federated’s culpability lingered, such as if they violated the state act requiring employees wear gas masks and if they should have had BAL on hand. Following the accident, the company promised to strengthen safety procedures, like employing gas detecting devices when material arrived.

Nearly twenty years later, Federated Metals found itself in the cross-hairs of the environmental movement, which had produced the first Earth Day and the Environmental Protection Agency. Learn about the U.S. Justice Department’s suit against Federated and the politics of pollution in Part II.