- World Events

During the early nineteenth century, the end of the Napoleonic Wars shaped the direction of the western world. After Napoleon’s defeat in the Cossacks (Russia) in 1814, the western powers reshaped the international order. To this end, the European powers that defeated Napoleon’s imperial ambitions (Russia, Great Britain, Prussia, and Austria) met in 1814-1815 in Vienna to create a new system of alliances that would keep the peace in Europe for the next 100 years. Called the Congress of Vienna, these meetings built a new international order based on the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, creating a “balance of power” system throughout the region.[1] This framework of negotiations continued to meet annually until 1822, when meetings met more sporadically. The Congress of Vienna was the first attempt by nation states in the modern period to create a system of peace that would be long-lasting, internally strong (which would be problematic due to the exclusion of the Ottoman Empire), and fair.[2]

- National Events

The “Era of Good Feeling,” embodied by the Presidency of James Monroe (1817-1825), defined the decade. The Democratic-Republicans, a party solidified under President Thomas Jefferson, became the dominant party in the United States. The War of 1812, bitterly fought between the United States and Great Britain, had strained the young republic, especially for a young territory-turned-state like Indiana. As historian Logan Esarey notes, “the first results of the War of 1812 were disastrous. The inroads of the Indians broke up many settlements.”[3] The election of 1820 saw President Monroe reelected to the Presidency with all electoral votes except one. This sweeping mandate reaffirmed the public’s trust in the Democratic-Republicans and Monroe’s vision for the United States.[4]

Yet the era was not without controversy. The hotly debated Missouri Compromise of 1820 created a balance of power between the slave states of the south and the free states of the north. The law called for Missouri’s admittance as a slave state and Maine as a free state, and prohibited slavery from the Louisiana Territory north of the 36° 30´ latitude line.[5] This was a compromise created out of various bills passed by both the House and the Senate who could not agree on whether to admit Missouri as a slave or free state. The law would remain in effect until the Kansas-Nebraska was passed in 1854. The debate about slavery was an instrumental part of Indiana’s own founding, with factions on every side.

- State Events & Legislative Responses

Indiana officially became a state on December 11, 1816, but the push for statehood traces back to before the War of 1812. Due to battles between British-leaning Native Americans and the United States, the Indiana Territory did not have the 60,000-residents status until after the conflict. Nevertheless, on April 19, 1816, the United States Congress passed the Enabling Act, which allowed for Indiana to petition for statehood.[6] Delegates met in Corydon in the summer of 1816, and on June 29, they signed the newly-drafted constitution. This new constitution created a General Assembly, comprised of a House of Representatives and a Senate, with members serving one and three years, respectively.[7] The state constitution also authorized the General Assembly to create a primary and secondary public education system, which included Indiana University[8]

During its first ten years, the General Assembly faced many challenges, but the issue that divided its legislators the most was slavery. Admitted to the union in 1816 as a free state, Indiana nonetheless was politically fragmented on the issue. Indiana’s first Governor, Jonathan Jennings, led a wing of fiercely anti-slavery Democratic-Republicans (the only party of consequence in Indiana at the time). On the other side, the James Noble faction was pro slavery and the William Hendricks faction was neutral on the conflict.[9] To settle these divisions, the General Assembly passed a measure in 1816 that outlawed “man-stealing,” which authorized indentured servitude only if the claimant could substantiate his case in court, otherwise it was considered slavery and illegal under the Indiana Constitution.[10] This ensured a compromise that kept all parties happy but allowed some forms of slavery in Indiana well into the 1830s.[11]

Other pressing matters in the first ten years of Indiana’s statehood included funding, construction of infrastructure, and selecting a new state capital. An Ohio Falls Canal, along the Ohio River, was proposed with financial allotments enacted by the General Assembly in 1818. However, by 1825, the canal project collapsed; poor management of its finances and Kentucky’s finished Ohio River Canal destroyed any chances of Ohio Falls Canal’s completion.[12] Yet, these setbacks only served as a catalyst for future internal improvements. In 1820 and 1823, the General Assembly passed roadway legislation that, “provided for twenty-five roads along definite routes through various counties, including five that were to be routed to the site of the new seat of government [Indianapolis].”[13] Costing over $100,000, these new roadway systems began the layout of Indiana’s infrastructure.

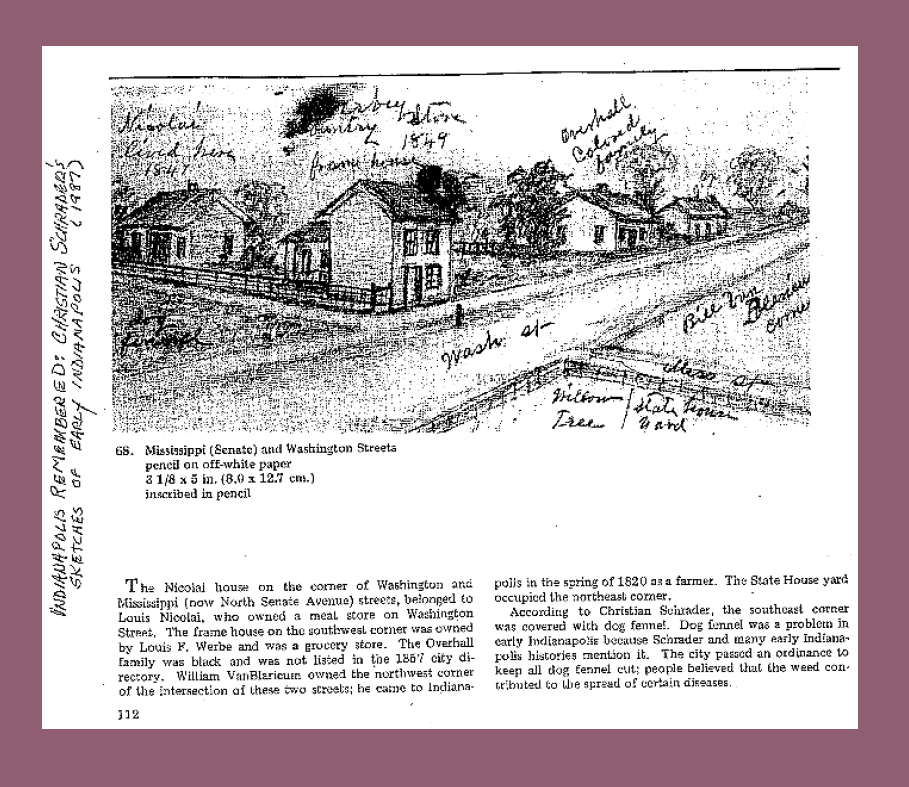

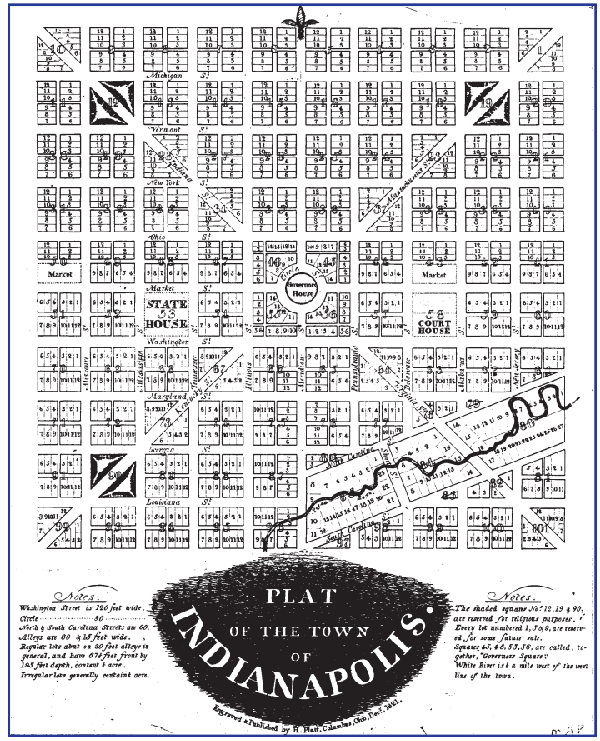

While Corydon served the state well as its first capital, northern migration facilitated the need for a more centralized seat of government by 1820. Named “Indianapolis” by state Representative Jeremiah Sullivan, the new state capital was surveyed by Alexander Ralston and Elias P. Fordham. Ralston, a surveyor and city planner who had worked in Washington, D.C., surveyed plats for Indianapolis in a similar design to the nation’s capital. In 1822, the General Assembly approved a law authorizing plat sales to facilitate the transfer of government and the construction of a Marion County Courthouse. In the 9th session of the General Assembly in 1824, Indianapolis was made the legal capital of the State of Indiana and chose Samuel Merrill, the State Treasurer, to oversee the arduous task of moving the government. It took eleven days to trek the 125 miles to the new capital, but Merrill and the Indiana General Assembly had finally arrived at their permanent home.[14]

- Notable Legislators

- Thomas Hendricks was a State Representative and State Senator from 1823-1831 and 1831-1834, respectively. He represented Decatur, Henry, Rush, and Shelby Counties. Wearing many hats, Hendricks served as a school superintendent, surveyor for Decatur County, and a Colonel of the Indiana militia in 1822. He was the first in the long and illustrious Hendricks family line to be in Indiana public service. His brother, John Hendricks, also served in the Indiana General Assembly and his nephew Thomas A. Hendricks later became the twenty-first Vice President of the United States.[15]

-

Justice Isaac Blackford, courtesy of Courts in the Classroom. Isaac Newton Blackford was the first Speaker of the Indiana House of Representatives, serving in the role from 1816-1817. Born in New Jersey and a graduate of Princeton, Blackford began his life in the Hoosier state as the Washington County Recorder. After a stint in the Indiana House of Representatives as its first Speaker, he went on to become an Indiana Supreme Court Justice, a role he filled until 1853. While never elected to higher office, he was appointed the United States Court of Claims in 1853, adjudicating cases until his death in 1859. Blackford is notable for his deep involvement in both the legislative and judicial branches of Indiana government, a role he pioneered and would have many follow in his footsteps.[16]

* See Part Two: Surveying, the First Statehouse, and Financial Collapse (1826-1846)

- Session Dates and Locations, Number of Legislators, Number of Constituents[17]

- 1st General Assembly: November 4, 1816-January 3, 1817. 10 Senators and 30 Representatives. Roughly 6,390 constituents per Senator and 2130 constituents per Representative.

- 2nd General Assembly: December 1, 1817-January 29, 1818. 10 Senators and 29 Representatives. Roughly 6,390 constituents per Senator and 2,203 constituents per Representative.

- 3rd General Assembly: December 7, 1818-January 2, 1819. 10 Senators and 28 Representatives. Roughly 6,390 constituents per Senator and 2,282 constituents per Representative.

- 4th General Assembly: December 6, 1819-January 22, 1820. 10 Senators and 29 Representatives. Roughly 6,390 constituents per Senator and 2,203 constituents per Representative.

- 5th General Assembly: November 27, 1820-January 9, 1821. 10 Senators and 29 Representatives. Roughly 14,171 constituents per Senator and 5,075 constituents per Representative.

- 6th General Assembly: November 19, 1821-January 3, 1822. 16 Senators and 44 Representatives. Roughly 9,199 constituents per Senator and 3,345 constituents per Representative.

- 7th General Assembly: December 2, 1822-January 11, 1823. 16 Senators and 44 Representatives. Roughly 9,199 constituents per Senator and 3,345 constituents per Representative.

- 8th General Assembly: December 1, 1823-January 31, 1824. 16 Senators and 46 Representatives. Roughly 9,199 constituents per Senator and 3,200 constituents per Representative.

- 9th General Assembly: January 10, 1825-February 12, 1825. 17 Senators and 46 Representatives. Roughly 8658 constituents per Senator and 3,200 constituents per Representative.

- The 1st-8th General Assemblies met in Corydon, IN and the 9th was the first General Assembly that met in the new capital of Indianapolis.

[1] Stella Ghervas, “The Congress of Vienna: A Peace for the Strong.” History Today, last modified 2014, accessed September 11, 2014, http://www.historytoday.com/stella-ghervas/congress-vienna-peace-strong.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Logan Esarey, History of Indiana (Bloomington: Hoosier Heritage Press, 1969), 209.

[4] For an overview of this period, see “American Political History: “Era of Good Feeling.” Eagleton Institute of Politics: Rutgers University, last modified 2014, accessed September 4, 2014, http://www.eagleton.rutgers.edu/research/

americanhistory/ap_goodfeeling.php.

[5] “Annals of Congress, House of Representatives, 16th Congress, 1st Session, Pages 1587 & 1588 of 2628.” A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 – 1875: Library of Congress, last modified July 30, 2010, accessed September 4, 2014, http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/ampage?collId=llac&fileName=036/llac036.db&recNum=155.

[6] James H. Madison, The Indiana Way: A State History (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1986), 50.

[7] Ibid, 53.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Jacob Piatt Dunn , Indiana and Indianans. (New York and Chicago: American Historical Society, 1919), 334

[10] Ibid, 341.

[11] James H. Madison, The Indiana Way, 54.

[12] Justin E. Walsh, The Centennial History of the Indiana General Assembly, 1816-1978 (Indianapolis, Indiana Historical Bureau, 1987), 24.

[13] Ibid, 26, f.117.

[14] Ibid, 14-16.

[15] Charles W. Calhoun, Alan F. January, Elizabeth Shanahan-Shoemaker and Rebecca Shepherd, A Biographical Directory of the Indiana General Assembly, Volume 1: 1816-1899 (Indianapolis, Indiana Historical Bureau, 1980), 178.

[16] Minde C., Richard Humphrey, and Bruce Kleinschmidt, “Biographical Sketches of Indiana Supreme Court Justices,” Indiana Law Review 30, no. 1 (1997): 333.

[17] This data is compiled from two major sources: Charles W. Calhoun, Alan F. January, Elizabeth Shanahan-Shoemaker and Rebecca Shepherd, A Biographical Directory of the Indiana General Assembly, Volume 1: 1816-1899 (Indianapolis, Indiana Historical Bureau, 1980), 437-446 and James H. Madison, The Indiana Way, 50, 59, 325.