* See Part One: Statehood, Slavery, and Constitution-Drafting (1815-1825)

Indiana’s Geological Survey

One of the more daunting tasks asked of the legislature was establishing a geologic survey of the state. Its origins date to 1830, when the General Assembly passed a resolution calling for the state’s first geologic survey connected with a professorship at Indiana University. This plan failed and the issue was not readdressed until 1836, when the General Assembly passed a new resolution calling for the creation of a geologic survey, led by twenty-seven year old David Dale Owen. Starting in 1837, Owen surveyed the state’s southern half and made his way northward. His primary task involved marking the delineation of coal and mineral deposits.[1]

Owen also perfected a method for determining the depth of coal deposits, which stipulated that once miners discovered limestone displaying specific fossils, no more coal was underneath. Owen’s reports to the General Assembly in 1837-39 gave legislators a wide range of information about the geologic properties of the state, including a topographical analysis and exact measurements of coal and mineral deposits. Due to his superb findings on the first geological survey, the General Assembly even consulted Owen on future geological projects up until his death in 1860. Owen’s dedication to science and exact methods inspired generations of geologists interested in Indiana and the Midwest.[2]

The First State House in Indianapolis

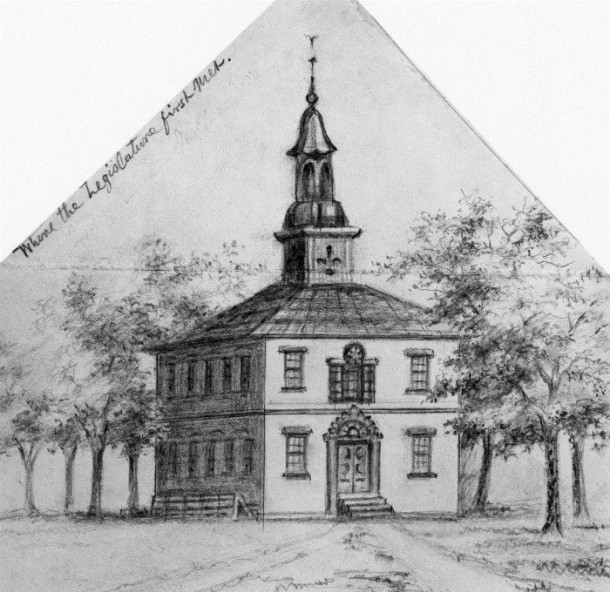

While the current state house in Indianapolis remains a hub for visitors and legislators alike, it was not the city’s first permanent seat of state government. The first state house in Indianapolis was completed in 1835 and designed by New York architects Ithiel Town and Alexander Jackson Davis, whose designs won approval from the Indiana General Assembly in 1831. A year before, the General Assembly authorized the construction of a new state house, with funding supplied through the sale of land plots within the city.[3] Construction began in 1832 with an original cost of $58,000 but an accelerated schedule grew costs to $60,000.[4] The builders’ speed insured the state house’s opening in December 1835, just in time for the incoming session of the Indiana General Assembly.

Town and Davis’ derived inspiration from Greco-Roman architecture; the state houses’ design resembled a temple surrounded by Doric columns like that of the world-famous Parthenon. Above the temple stood a rotunda dome influenced by Italian Renaissance style.[5] The state house’s visage contradicted much of the architecture in early Indianapolis. One legislator noted the building’s “striking contrast with the log huts interspersed through the almost ‘boundless contiguity of shade’ which surrounds it.”[6] The state house ushered in a new era for Indianapolis, filled with architectural marvels and urban transformation.

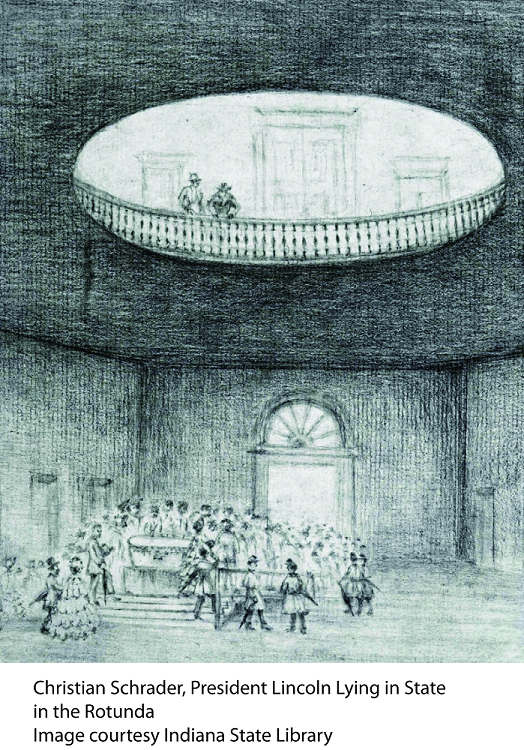

The state houses’ most notable visitor, Abraham Lincoln, also had humble roots in the Hoosier state. After his childhood years in Indiana, Lincoln visited the statehouse in 1861 as President-Elect of the United States and his body returned with a funeral procession after the assassination in April 1865.[7] The building’s poor materials, mostly of wood and stucco, brought the collapse of the roof in the summer of 1867. The building went through numerous repairs before the Indiana General Assembly approved the construction of a new state house in 1877. The original Indianapolis state house was demolished the same year.[8]

Internal Improvements and Financial Collapse

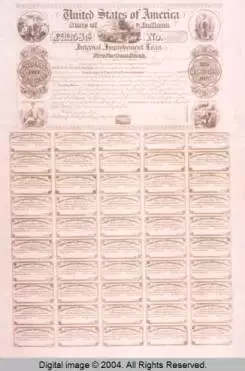

During the early years of the American republic, the policy that united most legislators and the public was “internal improvements,” which today we might call “infrastructure.” No state caught this fever quite like Indiana. Inspired by the successful opening of Fort Wayne’s Wabash and Erie Canal in July 1835, the General Assembly passed the Massive Internal Improvements Act of 1836.[9] The act, strengthened with over $10,000,000 through loans, proposed the creation of interconnected canals, turnpikes and railroads throughout the entire state. It was supposed to come under budget and take only ten years to finish.[10]

The economic Panic of 1837 and the dissolution of the Second Bank of the United States left the country gripping with economic hardship. This hit the internal improvements plan in Indiana dramatically, with construction costs ballooning over $10,000,000 and leaving little to no funds for repair costs. By August, 1839, none of the railroad, canal, or turnpike projects were finished and implementation stopped when the state ran out of funds.[11] State bonds, sold to citizens after the state’s land sales left the plan short, could not be paid back. Indiana’s state debt increased to, “$13,148,453 of which $9,464,453 was on account of the internal improvement system.”[12] By 1846, the General Assembly passed the Butler Bill, which funded the state debt two ways: revenues from the successful Wabash and Erie Canal and raising tax revenues.[13] These massive tax increases were hard on citizens and left many in the state with ill feeling towards unmanageable government spending. The financial failure of the internal improvement system heavily influenced the new state constitution of 1851, which required strict limits on government expenditures and enforcement of tax collection.

Notable Legislators

- John Finley

-

Courtesy of Waynet.org John Finley, the state’s first Poet-Legislator, served in the Indiana House of Representatives from 1828-1831. A newspaper editor by trade, Finley’s greatest contribution came with the publication of his poem “The Hoosier’s Nest” in 1833. Finley’s use of the term “Hoosier” in literature helped garner the term respect, rather than its traditionally pejorative meaning of “country backwoodsman.” He also owned and edited the Richmond Palladium from 1831-1834 and published a book of poems, including “The Hoosier’s Nest,” in 1860. He died in Richmond, Indiana in 1866.[14]

- John Ewing

- Born in Cork County, Ireland in 1789, John Ewing represented Vincennes and Knox County as a State Senator from 1825-1833 and again from 1842-1845. He was also a United States Representative from 1833-1839. Ewing’s success as politician came with equal scorn. His home was set on fire multiple times due to his staunch Whig party beliefs in an era of Democratic domination. His most valiant performance as a legislator came with his very public battle against State Representative Samuel Judah. Judah’s General Assembly bill re-chartering the financial benefits of then-defunct Vincennes University pushed Ewing to come home from the U.S. Congress, regain his State Senate seat, and defeat the bill though both legislation and through the courts. While his plans failed (he lost his seat in 1845 and his reforms did not pass), Ewing’s commitment to sound financial policy earned him respect and honor as one of the longest serving State Senators from his era.[15]

* See Part Three: A New Constitution and the Civil War (1850-1865)

[1] For a detailed account of David Dale Owen, see Walter B. Henderson, “David Dale Owen and Indiana’s First Geological Survey,” Indiana Magazine of History 36, no 1, 1-15, accessed October 9, http://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/7194/8101.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Justin E. Walsh, The Centennial History of the Indiana General Assembly, 1816-1978 (Indianapolis, Indiana Historical Bureau, 1987), 132.

[4] Dorothy Riker and Gayle Thornbrough, eds., Messages and Papers Relating to the Administration of Noah Noble, Governor of Indiana, 1831–1837 (Indiana Historical Collections, Vol. XXXVIII; Indianapolis, 1958), 351-352, accessed October 22, 2014, https://archive.org/stream/messagespapersre55nobl#page/350/mode/2up.

[5] James A. Glass, “The Architects Town and Davis and the Second Indiana Statehouse,” Indiana Magazine of History 80, no. 4 (December 1984), 335-337, accessed October 9, 2014, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27790832.

[6] Walsh, Centennial History, 132.

[7] For a detailed description of Lincoln’s visits to Indianapolis, see George S. Cottman, “Lincoln in Indianapolis,” Indiana Magazine of History 24 (March 1928), 1-14.

[8] Glass, “The Architects Town and Davis,” 337.

[9] Margaret Duden, “Internal Improvements in Indiana: 1818-1846,” Indiana Magazine of History 5, no. 4 (December 1909), accessed October 22, 2014, http://www.jstor.org/stable/view/27785234, 163.

[10] George S. Cottman, “The Internal Improvement System of Indiana,” Indiana Magazine of History 3, no. 3, accessed October 22, 2014, http://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/5612/4946, 119.

[11] James H. Madison, The Indiana Way: A State History (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1986), 83.

[12] Margaret Duden, “Internal Improvements in Indiana,” 168.

[13] Ibid, 169.

[14] Walsh, Centennial History, 124. Calhoun, January, Shanahan-Shoemaker, and Shepherd, Biographical Directory, 126.

[15] Walsh, Centennial History, 126-129. For Ewing’s government positions and elections, see Charles W. Calhoun, Alan F. January, Elizabeth Shanahan-Shoemaker and Rebecca Shepherd, A Biographical Directory of the Indiana General Assembly, Volume 1: 1816-1899 (Indianapolis, Indiana Historical Bureau, 1980), 437-446.