During the Progressive Era, Black women were often excluded from both white reform initiatives and male-dominated Black organizations. In response, Black women across the nation formed local clubs that allowed them to exercise agency and agitate for reform. The club movement was especially popular in Indianapolis. Editor Nina Mjagkij found that, “Between 1880 and 1920, Indianapolis’s black club women created more than five hundred clubs that addressed a wide range of social issues and laid the foundation for political activism.”[1] These clubs comprised educated upper-middle class women who sought to address problems such as urbanization, racial and gender barriers, education, and public health.[2]

Educator and reformer Ada B. Harris led the Black women’s club movement in Norwood, a historic neighborhood located in Southeast Indianapolis. The previous Untold Indiana Blog commemorated Harris’ decades-long career as an educator at Harriett Beecher Stowe School No. 64, one of the only public schools for Black children in Indianapolis. It also discussed her tireless work to fundraise and build communal spaces in the segregated city. This second blog will examine her leadership in the Black women’s club movement and how it related to the national Black Progressive movement.

Black Civic Involvement & Women’s Suffrage

Harris dedicated much of her time advocating for Black women’s suffrage and participating in civic projects. In 1894, Harris helped establish the Corinthian Baptist Church’s Women’s Club, which later became the Woman’s Civic Club. With over 300 members, the club encouraged Black women’s participation in politics by offering education about voting, hosting political discourse, and inviting prominent speakers to Norwood.[3] In 1904, they hosted prominent reformer May Wright Sewall at the A.M.E. Chapel for a fundraising event.[4] Harris herself often spoke to club members, discussing the ideology of major civil rights activists such as W. E. B. Dubois. The Woman’s Civic Club often collaborated with other clubs and organizations in Indianapolis, including the church’s Men’s Civic Club, the Good Citizens League, and the Flanner Guild.

In 1917, Harris volunteered to help register women for the Indianapolis Woman’s Franchise Leagues’ upcoming constitutional convention.[5] The League was one of the leading suffragist groups in the city and instrumental in organizing public rallies such as a statewide automobile tour in 1912 and marching to the statehouse in 1913.

Women won the right to vote in 1920 and Harris soon mobilized to educate Black women on political matters and encourage them to vote. In 1925, Harris held a “nonpartisan citizenship school,” at the YWCA on North West and Twelfth Street to “inform the women on the principles of the leading political parties and the issues of the campaign.” The Indianapolis News reported that over 100 Black women attended.[6] She also served on a women’s political committee which helped involve women in local politics. Throughout her career, she also spoke at various associations and organizations on how to register and vote, even becoming a public notary and holding “voting parties” in Norwood.[7]

Harris’s ideas of civic duty and virtue did not end at the ballot box. During World War I, Harris founded the Franchise Economy Club, which coincided with the national rationing movement. Members learned homespun canning techniques for a myriad of vegetables, including “green grapes, rhubarb, beans, peas and greens.”[8] Harris was so dedicated to the conservation of foodstuffs on the homefront that she traveled to West Lafayette to attend Purdue University’s conservation school in 1918. Notably, she was the only Black student to enroll in this course.[9] Learning cutting edge-methods for canning and food preservation, Harris would return to Norwood and disseminate this information to the public through local classes. She even converted an old building into a modern kitchen to aid her teaching.[10] These many activities demonstrate Harris’s deep commitment to both obtaining the vote and Black political participation.

Women’s Improvement Club & Health Initiatives

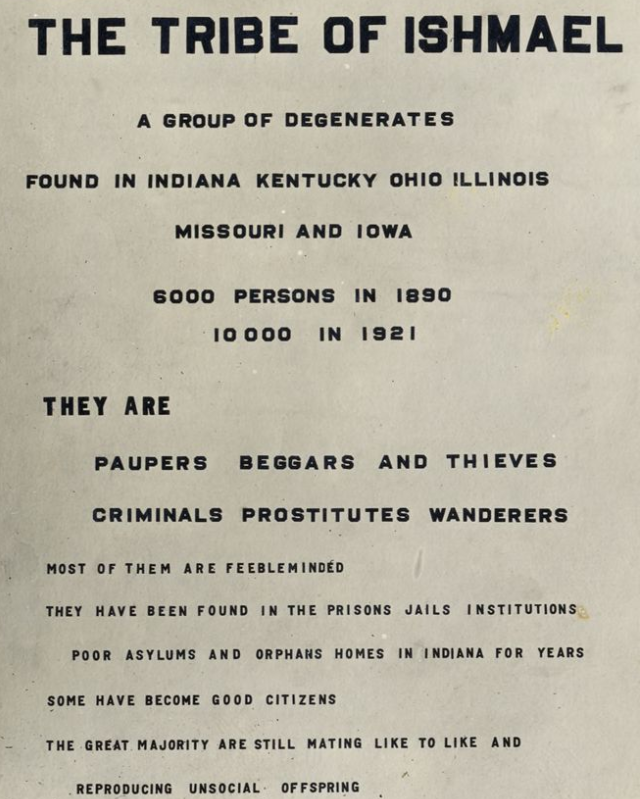

While Harris was involved in numerous clubs and organizations, perhaps her most important work stemmed from her leadership of the Women’s Improvement Club (WIC). Founded by Lillian Thomas Fox in 1904 as an exclusive literary club for upper-middle-class Black women, the members soon decided to pursue philanthropic ventures. At the time the local hospital refused to open a tuberculosis ward for Black patients, leaving a devastating gap in Black healthcare.[11] Additionally, Norwood struggled with underdeveloped infrastructure and poor sanitation, increasing the risk of disease for its residents.[12] WIC decided to open a fresh-air camp where Black tuberculosis patients could rest and receive care.

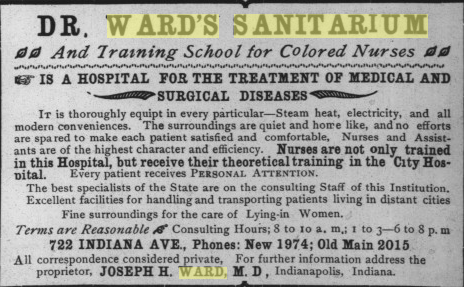

Already familiar with grassroots organizing and fundraising, Harris was instrumental in establishing the Oak Hill Camp. Meeting minutes show that she co-led the club committee responsible for establishing Oak Hill, and scoped out possible locations for the camp herself. In addition, she headed fundraising and organizational efforts to buy supplies for the camp and solicit Black physicians and nurses to care for patients.[13]

The Oak Hill Tuberculosis Camp opened in spring of 1905 and treated six patients. According to club member Lee Johnson, “the setting was very beautiful for the patients, located on a high hill with grand oak trees spreading their shady boughs over a tiny stream that trickled at the base.”[14] The Indianapolis News noted that Oak Hill was one of the only healthcare resources for Black Tuberculosis patients in Indianapolis. The camp soon had a waiting list of patients.[15] Until its closure in 1916, Oak Hill was annually organized, sponsored, and funded by the philanthropy of WIC. Running on a shoestring budget of charity funds, WIC solicited volunteers to help operate the camp and many Black physicians and nurses donated their personal time.

Club women also went beyond the camp, launching city-wide educational campaigns and facilitating trainings for Black nurses otherwise barred from white training programs to treat tuberculosis patients. They also attempted to lobby the City Hospital to build a cottage for Black patients, but these efforts proved unsuccessful.[16]

In 1916, the camp was closed but WIC continued its work aiding tuberculosis patients. They loaned tents to the homes of patients, assisted them in finding other healthcare services, and provided transportation for many. They also continued facilitating nurse training programs and bought an official club cottage at 535 Agnes Street in 1922. The club would continue its various tuberculosis initiatives until the 1960s, when medical advances reduced the threat of tuberculosis.[17] As a founding member of the club and a major force for the camps’ organization and fundraising, Harris helped address a major and tragic gap in Black healthcare.

Conclusion

Harris exemplifies the Black Progressive club woman movement in her devotion to the period’s philosophy of Black self-help and improvement through local, grassroots organization. Originally excluded from Progressive reform, Black club women across the nation such as Harris were able to claim the Progressive philosophy for their own communities and causes, namely that of suffrage and racial inequality. In doing so, Harris and other women emboldened their local communities to be active agents for change.

By advocating for public education, encouraging Black women’s political participation, and helping to provide health care to TB patients, Harris enhanced the living standards of Norwood. Her work also empowered Black citizens to agitate for their own welfare, paving the way for the future Civil Rights Movement. In short, Black reform went beyond simply improving local communities and, by upholding standards of excellence, these reformers made a compelling argument that they too deserved a proverbial seat at America’s dinner table. They sought an equal chance. When asked about her work in Norwood, Harris stated,

“My field has been small in Norwood, but it has been plenty large enough for my abilities. At least I shall have spent my life for my race.” – Ada B. Harris[18]

When historians and current residents recount Norwood’s storied history, they ought to recognize one of their best reformers and advocates in Ada B. Harris.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Kisha Tandy, curator at the Indiana State Museum, for spearheading the marker application for Ada B. Harris and conducting the initial research into Harris’s life and legacy.

For Further Reading

Ferguson Rae, Earline. “The Woman’s Improvement Club of Indianapolis: Black Women Pioneers in Tuberculosis Work, 1903-1938.” Indiana Magazine of History 84, no. 3 (September 1998): 273-261.

Tandy B., Kisha. “Ada Harris: Civic Leader, Educator, and Entrepreneur.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. May 2023, https://indyencyclopedia.org/ada-harris/.

Citations

[1] Nina Mjagkij, Organizing Black America: An Encyclopedia of African American Associations (New York, NY: Garland Publishing Inc., 2001), 271-274.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Description of mock political debate given by women, Indianapolis News, October 27, 1892, 2, accessed newspapers.com; Announcement of Harris giving a speech at Corinthian Baptist Church, Indianapolis News, October 8, 1900, 11, accessed Newspapers.com; “Woman’s Club Notes,” Indianapolis Recorder, August 10, 1907, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.

[4] “In Colored Circles,” Indianapolis News, April 25, 1904, 13, accessed Newspapers.com.

[5] “Registration Week for Women of the City,” Indianapolis News, June 23, 1917, 18, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[6] “Organizing Voting School,” Indianapolis News, September 18, 1920, 19, accessed Newspapers.com; “Citizenship School Held,” Indianapolis News, October 2, 1920, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[7] “Registration Week for Women of the City,” Indianapolis News, June 23, 1917, 18, accessed Newspapers.com; Kisha B. Tandy, “Ada Harris: Civic Leader, Educator, and Entrepreneur,” accessed Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, May 2023, https://indyencyclopedia.org/ada-harris/.

[8] “Norwood Has an Economy Club,” Indianapolis Star, July 29, 1917, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.

[9] Article on Harris attending Purdue University for women’s conservation school, Indianapolis News, July 6, 1918, p. 9, accessed via Newspapers.com

[10] Article on Franchise Economy Club, Indianapolis News, January 19, 1918, 11, accessed Newspapers.com; article on Harris attending Purdue University for women’s conservation school, Indianapolis News, July 6, 1918, 9, accessed Newspapers.com; “Norwood Cooking Class,” Indianapolis Star, August 4, 1918, 19, accessed Newspapers.com.

[11] Earline Rae Ferguson, “The Woman’s Improvement Club of Indianapolis: Black Women Pioneers in Tuberculosis Work, 1903-1938,” Indiana Magazine of History 84, no. 3 (September 1988): 237-261.

[12] “Bad Condition at Norwood,” Indianapolis Journal, September 30, 1903, 10, accessed Newspapers.com; “Measles at Norwood,” Indianapolis News, December 17, 1903, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

[13] Women’s Improvement Club Minute Books, 1919-1911, Women’s Improvement Club Collection, 1909-1965, Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, Indiana; Women’s Improvement Club Minute Books, 1916-1918, Women’s Improvement Club Collection, 1909-1965, Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, Indiana.

[14] Lee A. Johnson, “Woman’s Improvement Club Rounds Out Thirty Years of Philanthropic service in Valiant Fight Against Tuberculosis,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 7, 1934, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[15] “For Tuberculosis Sufferers,” Indianapolis News, August 4, 1911, 8, accessed Newspapers.com.

[16] Ferguson, “The Women’s Improvement Club,” 254.

[17] Lee A. Johnson, “Woman’s Improvement Club Rounds Out Thirty Years of Philanthropic service in Valiant Fight Against Tuberculosis,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 7, 1934, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[18] “Former ‘Bad’ Town Now an Ideal Spot,” Indianapolis Star, August 1, 1909, 25, accessed Newspapers.com.