You might never guess that several parts of Indianapolis lying well inside the city limits are built on old swamp lands. Turn back the clock to the 1940s and new homes and roads in southeast Broad Ripple are literally sinking into the earth. Turn it back another century still, and the hoot-owls and swamp creatures who easily outnumber humans in Marion County are living practically downtown. (In fact, the whole county was named for Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox” of Revolutionary South Carolina.)

Two old wetlands, sometimes called bogs or sloughs, played a fascinating part in the capitol city’s history.

Fletcher’s Swamp is long gone but used to sit just east of the Old North Side, between Cottage Home and Martindale-Brightwood. A couple of hundred acres in size, the swamp occupied an area more or less centered around the future I-65/I-70 interchange. Pogue’s Run flowed just to the south.

An article in the Indianapolis Journal on December 15, 1889, describes the setting. The author, probably the young journalist and historian Jacob Piatt Dunn, writes about an area northeast of Ninth Street and College Avenue:

To the boys of twenty-five years ago [circa 1864] this area was known as Fletcher’s swamp, and was a famous place for black and red haws, fox grapes and other wild fruits that only a youngster would think of eating. Fifty years ago [the 1830’s] this place was a verible [sic] dismal swamp, impenetrable even to the hunter except in the coldest winter, for it was a rare thing for the frost to penetrate the thick layer of moss and fallen leaves that covered the accumulated mass of centuries, and which was constantly warmed by the living springs beneath.

Today the old swamp area is within easy walking distance of Massachusetts Avenue, but you won’t find a trace of it. “About on a line with Twelfth Street” near the center of the swamp “was an acre, more or less, of high land,” a spot “lifted about the surrounding morass.” The writer — again, likely J.P. Dunn — thought that this high, dry spot had once been a “sanctuary” for “desperadoes and thieves who preyed upon the early settlers.” (Northern Indiana swamps, like the one around Bogus Island in Newton County, were notorious hideouts for counterfeiters and horse thieves. Elaborate hidden causeways were said to give entrance to remote islands on the edge of the vast Kankakee Swamp, the “Everglades of the North.”)

In the 1830s, Fletcher’s Swamp became one of the stops on the Underground Railroad. Calvin Fletcher, a Vermont-born lawyer and farmer whose 1,600-acre farm once included most of the Near East Side, was an active abolitionist during the days of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. For several decades, many Hoosier opponents of slavery, primarily Quakers, guided hundreds if not thousands of African American freedom seekers toward Westfield in neighboring Hamilton County. (Westfield was a major Quaker settlement before the Civil War, and other “stations” around Indianapolis focused on getting freedom seekers there.) Wetlands, usually hard to penetrate, were an ideal hideout, since the bloodhounds that bounty-hunters used to track freedom seekers lost their scent there. And like the counterfeiters on Bogus Island, refugees from slavery used retractable wooden “steps” across the swamp to help avoid detection.

Although not Quakers themselves, Fletcher and his family helped many African Americans travel north to Michigan and Canada.

Fletcher also owned the swamp the freedom seekers hid in. The Indianapolis Journal recalled one story about the place in 1889:

Calvin Fletcher, Sr., became the owner of this swamp, or the greater part of it. Spring, summer, and autumn he was in the habit of riding horseback all around it. . . Mr. Fletcher delighted in the study of nature, especially in birds (and in the quiet of this swamp was bird life in sufficient variety for an Audubon or a Wilson), and he knew every flier and nest on its borders.

A tenant of a cabin near this swamp told the story that his attention was often attracted to Mr. Fletcher, for the reason that he rode out that way so early, and usually with a sack thrown over the horse’s neck. The curiosity of the dweller in the cabin was excited to that degree that, one morning, he furtively followed the solitary horseman. It was about sunrise, and he saw Mr. Fletcher hitch his nag to a sapling, take off the sack (which for some reason the narrator supposed to contain corn-bread and bacon), walk a little way into the covert, and then give a call, as if calling cattle. There was, in answer, a waving of elders, flags and swamp-grass, with an occasional plash in the water, and finally appeared the form of a tall, muscular negro, with shirt and breeches of coffee-sacking. He came silently out to the dry land, took the sack from the visitor’s hand, spoke a few words inaudible to the straining ears of the listener and hastily disappeared in the recesses of the swamps. So, after all, Mr. Fletcher’s favorite bird, and a very unpopular one in that day, too, was the blackbird.

The swamp might have had strange bedfellows during the Civil War. The dense thickets and morasses here were an ideal hideout for Confederate POW’s who escaped from the Union Army’s Camp Morton, which sat just west of here, near the future intersection of 19th Street and Central Avenue. Calvin Fletcher’s son, Stephen Keyes Fletcher, claimed in 1892 in the Indianapolis Journal: “During the war the swamp was this great hiding place for escaped prisoners from Camp Morton.”

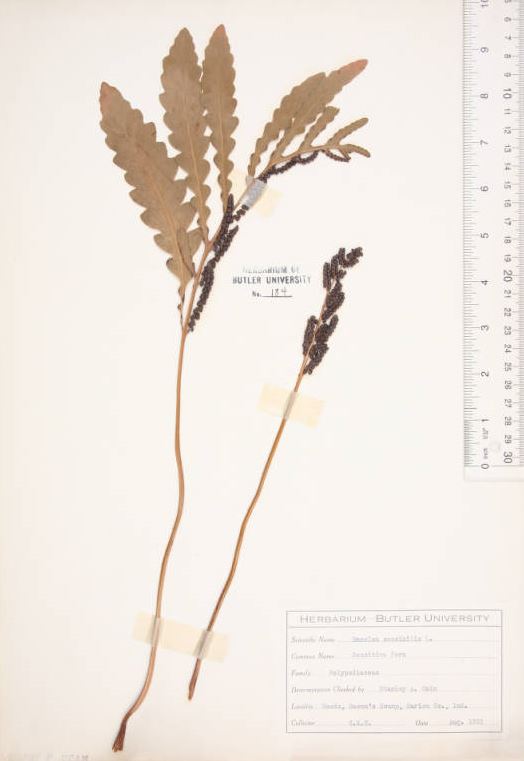

The original Butler University, which sat at 13th and College until 1875, was another neighbor of Fletcher’s Swamp. When a freedom seeker, aided by local abolitionists, escaped from the downtown jail and tried to get to the swamp on horseback, he ended up at Northwestern Christian University (as Butler was called) and was arrested on campus. “The capture of the negro brought on a heated battle among the students of the university, some of whom were from the South,” the Indianapolis Journal claimed in 1889. “A pitched battle followed between them and the black Republican students, which resulted in nothing more serious than some blackened eyes and ensanguined noses. The scene of this battle is now the playground for the children of the Indianapolis Orphan Asylum.”

What happened to Fletcher’s Swamp? Stephen Fletcher, who apparently inherited the property after Calvin’s death in 1866 — he ran a nursery nearby — told some of the story using terminology not employed today:

About this same time the negroes began flocking over from Kentucky and other Southern states. My father, being a great friend of the colored man, was inclined to provide them with homes and work as far as possible. After filling up everything in the shape of a house, I then let them build cabins at the edge of the swamp, on high ground, just north of the Belt railroad, and about where Baltimore Avenue now runs. I soon had quite a settlement, which was named by my brother, Dr. W.B. Fletcher, “Monkey Jungle,” and the location is known to this day [1892] by that name by those familiar with it then.

A writer for the News concurred in 1889:

The clearing of the swamp was an accident of President Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation. Hundreds of colored men, with their families, came from the South to this city. It was a class of labor new to Indianapolis, and for a time there was a disinclination to employ them. Mr. Fletcher, however, gave every man with a family the privilege of taking enough timber to build a cabin, and of having ground for a “truck patch,” besides paying so much a cord for wood delivered on the edge of the swamp. Quite a number of the negroes availed themselves of this offer of work and opportunity for shelter…

Calvin Fletcher, Jr., drained what was left of his father’s swamp in the 1870s by dredging it and connecting it to the “Old State Ditch.” Thus it shared the fate of thousands of acres of Hoosier wetlands sacrificed to agriculture and turned into conventional cropland.

An 1891 Journal article on the “State Ditch” calls Fletcher’s Swamp one of two “bayous” that threatened valuable property on the then-outskirts of Indianapolis.

The other “bayou” was the fascinating Bacon’s Swamp. Today, the area that used to be covered by this large Marion County bog is part of Broad Ripple. Although Google Maps still shows a lake there called Bacon’s Swamp, this is really just a pond, re-engineered out of what used to be a genuine freshwater wetland.

Like its neighbor a little to the south, Bacon’s Swamp was created by the melting Wisconsin Glacier. About 20,000 years ago, the ice left an indent on the land that filled with water. As limnologists (freshwater scientists) describe, the process of swamp formation, lakes age and die like living creatures, filling up with sediment and plant matter and gradually losing the oxygen in their depths. Bacon’s Swamp evolved into a peat bog, one of the southernmost in the United States.

Like Fletcher’s Swamp, it took its name from a prominent local farmer active as a stationmaster on the Underground Railroad. A native of Williamstown, Massachusetts, Hiram Bacon moved to this remote spot with his wife Mary Blair in 1821. (Bacon was 21 years old, had studied law at Williams College, but due to poor health joined a government surveying expedition to the Midwest at age 19. He liked Indiana and stayed.) Presbyterians, the Bacons became friends with Henry Ward Beecher, brother of the novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe, when he served as minister of Second Presbyterian Church downtown. Beecher often came out to Bacon’s Swamp in the 1840s, when this was a remote part of Marion County.

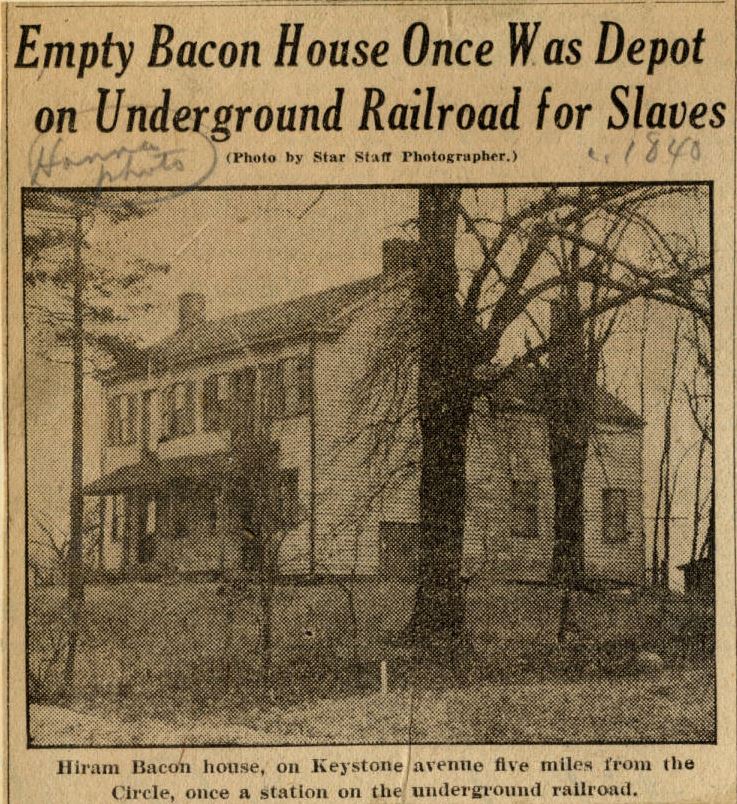

Hiram and Mary Bacon actively helped freedom seekers escape through the area. A 1931 article in the Indianapolis Star claimed that “The Bacon house stands on the east side of the road [now the paved Keystone Avenue], and the large barn was on the west side. In it was a wheat bin, which could be entered only from outside by a ladder. It was usually concealed by piles of hay. Here and in the bin in the cider house, the fugitives were hidden and conveyed after dark to the next depot . . . The matter was never discussed in public.” At night, freedom seekers hid out in the peat bog across from the Bacon dairy farm.

The 400-acre family farm was located approximately where Glendale Mall sits today. (Most of east Broad Ripple would have been deep in the morass back in the mid-1800s.) Empty in the 1930s, the site of the Bacon farmhouse is occupied today by the Donut Shop at 5527 N. Keystone.

Around 1900, this area, now considered part of Broad Ripple, was called Malott Park. Not to be confused with today’s Marott Park, Malott Park was a small railroad town later annexed by Indianapolis. Barely a century ago, it was one of the last stops on a railroad line that connected northern Marion County with the Circle downtown. Until World War II, Glendale was a far-flung place out in the country.

Walter C. Kiplinger, a chemistry teacher and tree doctor for Indianapolis public schools, wrote a fascinating article about the peat bog for the Indianapolis News in 1916. The part of the bog he described was about a mile north of the State Fairgrounds, near 50th Street and Arsenal Park. Now a major residential neighborhood, a hundred years ago it sounds like GPS coordinates were the only thing we’d recognize about the place:

You can reach it very easily if you have a machine [car] by taking the White River road to Malott Park, but when the spring rambling fever comes it is much more easy to go cross-country. It is just a pleasant afternoon’s hike there and back. . . If common courtesy is observed in closing gates and keeping off fields where the crops might be injured, the owners of the farm lands usually do not enforce their trespass notices. . .

How much peat there is in Bacon’s slough or how thick the bed is, no one seems to know. . . Whatever the average depth, it is as truly a peat bog as any in Ireland.

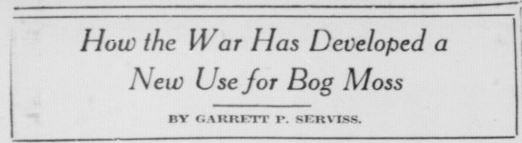

Serious proposals to harvest peat in Indianapolis were mentioned in the press from 1905 until the 1920’s, when the idea was apparently dropped. Other parts of Indiana, especially up north, also explored the possibility of using peat as a substitute for coal. During World War I, the U.S. and Canada exported sphagnum moss from North American peat bogs to Europe, where a cotton shortage had led army doctors to experiment with peat bandages on the Western Front. The moss served as a kind of natural antibiotic and was a success when used to dress wounds. (The story made it into the South Bend News-Times in 1918.)

Use of peat has always been widespread in Europe. Not a fossil fuel, it emits an odorless, smokeless heat and an “incredible ambiance.” For millennia, it has served as a cheap heat source in rural Ireland and Britain (where it also gives the “smoky” flavor to Scotch whisky.) The Indianapolis News ran an article about “inexhaustible” Irish peat in 1916, informing Hoosiers that “Mixed with crude molasses from sugar mills it is also used as a forage for cattle, while semi-successful efforts have been made to convert the vegetable fibers into a cheap grade of paper.” In 1929, a massive 40% of the Soviet Union’s energy came from peat, but today, large-scale industrial harvesting is only common in Ireland and Finland.

As an alternative fuel source, peat nearly became a reality in central Indiana in the early 1900s. E.H. Collins, a “scientific” farmer from Hamilton County, touted that the “earth that would burn” in the summer of 1905.

Collins owned a farm a mile north of the State Fairgrounds, in the vicinity of Bacon’s Swamp. An article on August 19 in the Indianapolis News refers to the 30-acre peat bog he “discovered” as the “Collins Bog.” The farmer estimated that it held about 400,000 tons of the fuzzy stuff.

The 1905 article in the Indianapolis News is a strange flashback, envisioning a grand future that never really came about.

The announcement that a good fuel deposit has been found at the city limits and can be drawn on in case Indianapolis gets into a fuel pinch is of great importance to a city that, thus far, has been left out of practically every fuel belt in Indiana in recent years — in fact, since she was the very center of the stove wood belt. Too far west to be in the gas belt, too far east to be in the coal fields and outside of the oil territory, Indianapolis, since the old cordwood days, has been a negative quantity in the state’s fuel supply. . .

The discovery of good peat deposits around Indianapolis calls attention to the fact that Indiana sooner or later is to come to the front as a peat-producing state.

Obviously, this never happened. Peat was briefly harvested in Bacon’s Swamp in the mid-20th century, as it was in a few other spots throughout northern Indiana, but the resource was mostly used for gardening, not as a rival to coal.

As Indianapolis’ economic downturn and “white flight” led to the explosion of Broad Ripple as a suburb in the 1950s, the swamp was more and more threatened. Conservationists were mostly ignored when they argued that the swamp protected creatures who keep insect populations in check and therefore help farmers and gardeners. In February 1956, three children drowned trying to save a puppy who had fallen through the ice in one of the lakes here, prompting residents in the area to push for “condemning” and obliterating the “deadly swamp.”

While the squishy, “bottomless” ground was a constant problem for developers — devouring roads in 1914 and 1937 — gradually only a tiny remnant pond was left, just west of Keystone Ave and a block south of Bishop Chatard High School. Yet the tree doctor Walter Kiplinger did remember one man who kept himself warm with a satisfying peat fire in Indianapolis back in the day.

“There used to be one from the ‘ould sod’ [Ireland] who lived in a shack near the hog pens east of the slough,” Walter C. Kiplinger remembered during World War I in the Indianapolis News:

His name was Michael O’Something-or-other, I’m not certain what, but he was a gentleman in the highest sense of the word. There was nothing hyphenated about his Americanism, but is a man any the worse American for having a bit of sentimental feeling for the old country in his makeup? Surely when one has a bit of Ireland’s own bog land in his own back yard, you might say, he has a perfect right to dig and use the peat for fuel. . .

Bacon’s Slough will probably go the way of similar places; but one should not be too pessimistic. The Irish may mobilize some St. Patrick’s Day, and go out and save it just for the sake of that peat bog. You can never tell.

Contact: staylor336 [at] gmail.com