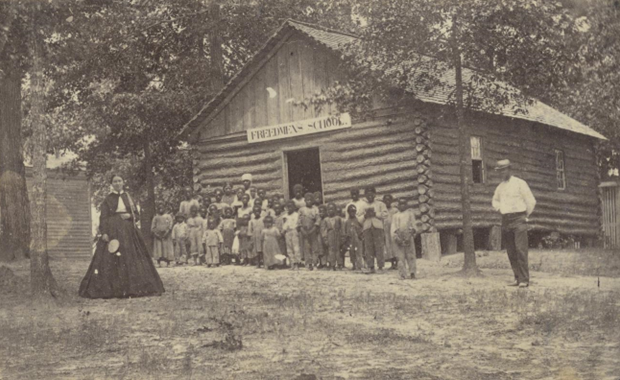

Despite its status as a free state in the federal union, Indiana maintained a complicated relationship with the institution of slavery. The Northwest Territory, incorporated in 1787, banned slavery under Article VI of the Articles of Compact. Nevertheless, enslaved people were allowed in the region well after lawmakers organized the Indiana Territory in 1800. As historians John D. Barnhart and Dorothy L. Riker noted, there were an estimated 15 people enslaved in and around Vincennes in 1800. This number only represented a fraction of the 135 slaves enumerated in the 1800 census. When Indiana joined the Union as a free state in 1816, pockets of slave-holding citizens remained well into the 1830s.

Fugitive slave laws, a core policy that before the Civil War, perpetuated the “dreaded institution.” The U.S. Congress passed its first fugitive slave law in 1793, which allowed for slave-owning persons to retrieve their human property in any state and territory in the union, even on free soil. Indiana, both as a territory and a state, passed legislation that ensured compliance with federal law. The controversial Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 exacerbated the problem, with many arrests, enslavements, and re-enslavements of African Americans in Indiana. Scholars estimate that 1,000-5,000 freedom seekers escaped bondage annually from 1830-1860, or roughly 135,000 before the Civil War.

Making matters more complicated, Indiana ratified a new constitution in 1851 that included Article XIII, which prohibited new settlement of African Americans into the state. Article XIII also encouraged colonization of African Americans already living in the state. The Indiana General Assembly even passed legislation creating a fund for the implementation of colonization in 1852. It stayed on the books until 1865. This, along with a litany of “black codes,” limited the civil rights of free African Americans and harsher penalties for African Americans seeking freedom. As historian Emma Lou Thornbrough observed, Indiana’s policies exhibited an “intense racial prejudice” and a fear of free, African American labor. One window into understanding complex history of fugitive slaves is by analyzing newspapers. Ads for runaways, fugitive slave narratives, and court case proceedings permeate Indiana’s historic newspapers. This blog will unearth some of the stories in Indiana newspapers that document the long and uneasy history of African American freedom seekers in the Hoosier state.

Runaway advertisements predominantly chronicled fugitive slavery in Indiana newspapers during the antebellum period. These ads would provide the slave’s name, age, a physical description, their last known whereabouts, and a reward from their owner. One of the earliest ads comes from the September 18, 1804 issue of the Indiana Gazette, while Indiana was still a territory. It described two slaves, Sam and Rebeccah, who had run away from their owner in New Bourbon, Louisiana. Sam was in his late twenties and apparently had burns on his feet. Rebeccah was a decade younger than Sam and “was born black, but has since turned white, except a few black spots.” This might have been a case of vitiligo, a skin pigment disorder. In any event, their owner offered a fifty dollar reward for “any person who will apprehend and bring back said negroes, or lodge them in any jail so that the owner may get them.”

On December 9, 1807, the Western Sun ran a similar ad with a small, etched illustration of a runaway slave. Slaveholder John Taylor offered thirty dollars for the capture and return of three slaves (two men and one woman) who had taken two horses and some extra clothes. “Whoever secures the above negroes,” Taylor said, “shall have the above reward, and all reasonable charges if taken within the state; or ninety dollars, if out of the state . . . .”

These ads escalated after Indiana’s statehood in 1816, leading to expansions of the role of local officials. As Emma Lou Thornbrough noted, African Americans “were sometimes arrested and jailed on the suspicion that they were fugitives enough though no one had advertised them.” For example, the Western Sun & General Advertiser published a runaway ad on June 27, 1818 asking for the return of Archibald Murphey, a fugitive from Tennessee who had been captured in Posey County. Sheriff James Robb, and not Murphey’s supposed owner, took it upon himself to run an ad for the runaway’s return. “The owner is requested to come forward [,] pay charges, and take him away,” the ad demanded.

Owners understood the precarious nature of retrieving their slaves, so some resorted to long ad campaigns in multiple newspapers. A slave named Brister fled Barren County, Kentucky in 1822, likely carrying free papers and traveling north to Ohio. His owner offered a $100 reward for his return for at least three months in the Western Sun & General Advertiser. He had also advertised in the Cincinnati Inquisitor, Vincennes Inquirer, Brookville Enquirer, Vandalia Intelligencer, and Edwardsville Spectator.

Other ads provided physical descriptions that indicated the toll of slavery on a human being. Two runaways, named Ben and Reuben, suffered from multiple ailments. Ben had his ears clipped “for robbing a boat on the Ohio river” while Reuben lived with a missing finger and a strained hip. Lewis, a fugitive from Limestone County, Alabama, had a “cut across one of his hands” that caused “one finger to be a little stiff.” They could also be rather graphic. The Leavenworth Arena posted an ad in its July 9, 1840 issue requesting the return of a slave named Smallwood, who scarred his ankles from a mishap with a riding horse; reportedly a “trace chain” wrapped around his legs, “tearing off the flesh.” The pain these men, among many others, endured from the years of their bondage was sadly treated as mere details in these advertisements.

While ads represented a substantial portion of newspaper coverage, articles and court proceedings also provided detail about the calamitous lives of fugitive slaves. First, court cases provide essential insight into the legal procedures regarding fugitive slaves before the Civil War. The Western Sun & General Advertiser published the court proceedings of one such case in its November 21, 1818 issue. John L. Chastian, a Kentucky slaveholder, claimed a woman named Susan as his slave and issued a warrant for her return. Corydon judge Benjamin Parke ruled in favor of Chastian on the grounds that Susan had not sufficiently demonstrated her claim to freedom and the motion for a continuance on this question was overruled. Even if Susan had been a free person, the legal system provided substantial benefits to the slaveholders, and since she could not demonstrate her freedom, she was therefore obligated to the claimant.

As for abolitionists, they faced court challenges as well. In 1843, Quaker Jonathan Swain stood before a grand jury in Union Circuit Court, “to testify in regard to harboring fugitive slaves, and assisting in their flight to Canada.” When asked to testify, Swain refused on grounds of conscience. The judge in the case granted him two days to reconsider his choice. When Swain returned, “he duly presented himself before the Judge, Bible under his arm, and declared his readiness to abide the decision and sentence of the Court.” The judge cited Swain in contempt and jailed him, “there to remain until he would affirm, or should be otherwise discharged.” This episode was one of many that demonstrated the intense religious and moral convictions of Quakers and their resistance to slavery.

By contrast, many of those who sought slaves faced little challenge. The Evansville Tri-Weekly Journal reported that Thomas Hardy and John Smith, on trial in the Circuit Court of Gibson County for kidnapping, were acquitted of all charges. The judge’s ruling hinged only on a fugitive slave notice. This notice provided “sufficient authority for any person to arrest such fugitive and take him to his master.” As with the case involving Susan, the alleged slaves procured in this case received less legal protection than the two vigilantes that captured them. These trends continued well into the 1850s through the end of the Civil War.

Second, numerous articles and narratives concerning fugitive slaves and free persons claimed as fugitives were published during the antebellum period. The passage of the federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, of which Indiana kept its obligation to enforce, exacerbated coverage. Some articles were merely short notices, explaining that a certain number of alleged fugitive slaves were passing through a town or getting to a particular destination. The Evansville Daily Journal ran a brief description in 1859 about two men “who had the appearance of escaped slaves, came upon the Evansville road, last night, and passed on to Indianapolis.” It was also reported that they “had a white adviser with them on the cars,” supposedly a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad. In another piece, the Journal wrote uncharitably about a “stampede of slaves” that:

. . . left their master’s roofs, escaped to the Licking river where they lashed together several canoes, and in disguise they rowed down the Licking river to the Ohio and crossed, where they disembarked and made a circuitous route to the northern part of Cincinnati.

After their travel to Cincinnati, the twenty-three fugitives began their route to Canada via the Underground Railroad.

Articles covering the arrest of fugitive slaves also filled the headlines. As an example, the New Albany Daily Ledger ran a piece in 1853 about two fugitive slaves captured in the basement of local Theological Seminary. Jerry Warner, a local, arrested them both and received $250 in compensation for their capture. The Evansville Daily Journal reported of the arrest of three fugitive slaves in Vincennes who were on their way to freedom in Canada. Two men, one from Evansville and another from Henderson, Kentucky, pursued and captured the fugitives nearly eight miles outside of the city. The fugitives defended themselves against capture, with one of them brandishing a pistol who “snapped it twice at the officer, but it missed fire.” The officers then transferred the fugitives to Evansville, who were supposedly returned to Henderson.

Conductors of the Underground Railroad also faced arrest for the aid of fugitive slaves. Another article from the Evansville Journal chronicled the arrest of a man known simply as “Brown” who aided four female slaves to an Underground Railroad stop at Petersburgh, Indiana. A US Marshal and a local Sheriff “charge[d] on the ‘worthy conductor,’ and he surrendered.” The officers returned Brown to the Henderson jail for processing. It was later discovered that he received $200 from a free African American for his last job. The Journal described Brown as a “notorious abolitionist, and if guilty of the thieving philanthropy with which he is charged, deserved punishment.” Indiana’s free state status did not lessen the prejudice against African Americans and abolitionists; it only obscured it.

One of the more elaborate, yet challenging methods fugitive slaves used to seek freedom involved shipping boxes. The Evansville Daily Journal reported of a fugitive slave captured aboard the steamer Portsmouth, a shipping vessel traveling from Nashville to Cincinnati. He was in the box, “doubled up like a jack-knife,” for five days before authorities discovered him and took the appropriate actions. The ship docked at Covington, Kentucky and they “placed the negro in jail to await the requisition of his owner.” It was learned later that the fugitive slave had an agreement with a widow to move to Ohio on condition that he work for her for a year. “He had fulfilled his part of the contract,” the Journal wrote, “and she was performing her stipulations, and would have enabled him to escape had it not been for the unlucky accident.” This story was also covered in the Terre Haute Daily Union and similar stories ran in later issues of the Journal, the Nashville Daily Patriot, and the Richmond Palladium.

Sadly, the ultimate risk for a fugitive slave was death, and Indiana newspapers chronicled these events as well. The Crawfordsville Weekly Journal published an article on August 16, 1855 detailing the death of a fugitive slave by drowning. It appeared to the authorities that the fugitive, resting near Sugar Creek in Crawfordsville, was discovered by a group of men and questioned about his status. Under pressure, the fugitive leaped into the water and tried to flee, which spurred one man to shoot off his gun in an attempt to stop him. As the Journal wrote, “this alarmed the negro, and he plunged beneath the waters, and continued to rise and then dive, until exhausted, and he sank to rise no more until life was extinct.” His body was discovered a few days later. While some deemed his death a mere drowning, others thought it more “suspicious.” The Journal continued:

Putting the most favorable construction on the circumstances, there was a reckless trifling with human life which nothing can justify. He was doubtless a fugitive, but they knew it not, and had no right to arrest him or threaten his life. They knew of no crime of which he had been guilty, and only suspected him of an earnest longing after that freedom for which the human heart ever pants; and because he acted upon this feeling, so natural and so strong, they threaten to tie and imprison, and when struggling with overwhelming waters, he is threatened with being shot if he does not return ; and then when strength and life were fast failing, stretched not forth a helping hand to save him from immediate death.

If the facts as stated be true, (of which we have no doubt,) there is high criminality, of which the laws of our country should take cognizance; and when the news of the negroe’s [sic] death shall have reached his owner, he will doubtless prosecute those men; it may be for murder in the second degree, or at least for the value of the slave.

The Journal eloquently elucidated why the application of fugitive slave laws, especially by vigilante citizens, harmed the civil rights and lives of both free people and those still in servitude (of which there were a mere few).

Free African Americans additionally faced threats to their lives and livelihood from the enforcement of fugitive slave laws. A well-known instance in Indiana regarded the arrest and release of John Freeman. Arrested and jailed on June 21, 1853, Freeman faced a charge from Pleasant Ellington of Missouri that he was one of his slaves. Freeman hired a legal team and after a lengthy trial that testified to his status as a free-born African American, he was released on August 27, 1853. It turned out that Ellington misidentified Freeman as a slave named Sam, who fled from servitude in Greenup County, Kentucky and likely escaped to Canada. Due to the diminution of his character, Freeman sued Ellington in civil court for 10,000; it was later ruled in favor of Freeman and he received $2,000 and additional unnamed damages. What Freeman experienced is but a snapshot into how fugitive slave laws harmed the rights of free people as well as slaves.

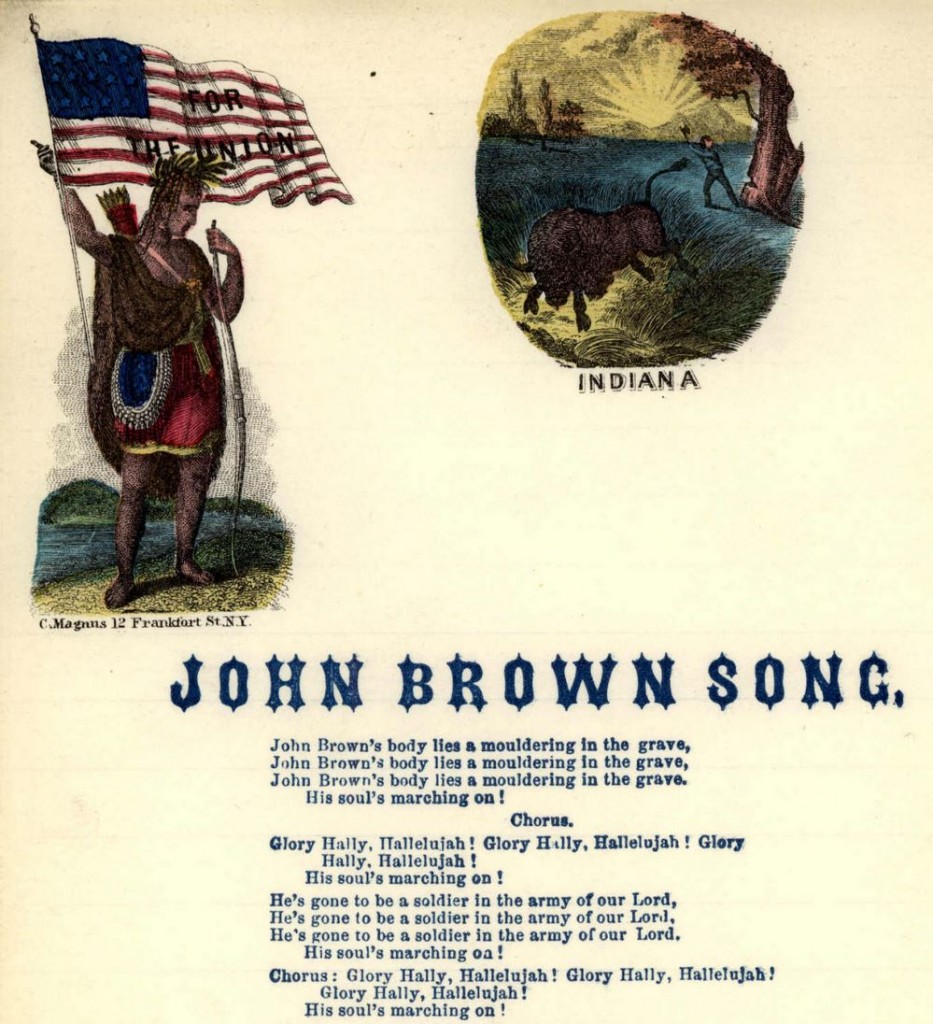

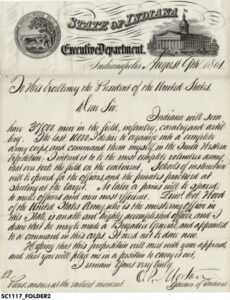

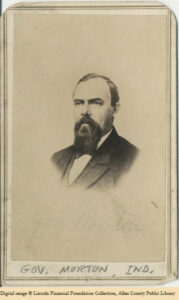

After the Civil War began, fugitive slaves continued to elicit concern, and coverage, in Indiana newspapers. In the spring of 1861, the Sentinel reprinted a piece from the Jeffersonville Democrat about the rise of fugitive slaves traveling through the Ohio River region: “the number of fugitive slaves caught on the Indiana side of the river, and returned to Kentucky within the past three months, is greater than that of any like period during the past ten years.” Kentucky’s government still offered a reward of $150 for each returned slave. That summer, the Indiana State Guard published President Abraham Lincoln’s thoughts on the issue. Lincoln, in a manner characteristic of his own political calculus, declared that Union soldiers were not “obliged to leave their legitimate military business to pursue and return fugitive slaves” but also cautioned that “the army is under no obligation to protect them, and will not encourage nor interfere with them in their flight.” The new President offered a nuanced position that possibly placated the Border States while satisfying the abolitionist wing of his own party. Realistically, it was a long way away from the Emancipation Proclamation.

The end of the Civil War brought the end of slavery as a federally-protected policy, and thus eliminated the need for fugitive slave laws. Their end brought a larger fulfillment of the Declaration of Independence’s commitment to the proposition that “all men are created equal.” Yet, the history of fugitive slaves often fell into tales of folklore and hyperbole. Looking at a primary source like newspapers helps to dispel many of the myths and provides nuance to the controversial subject of human enslavement in the United States. These stories represent a small fraction of the larger narrative about American slavery. To learn more, visit the Library of Congress’ page about fugitive slave ads in historical newspapers: https://www.loc.gov/rr/news/topics/fugitiveAds.html. You can also search Hoosier State Chronicles for more fugitive slave ads and articles.

Other Resources

Indiana Historical Bureau: Slavery in Indiana Territory