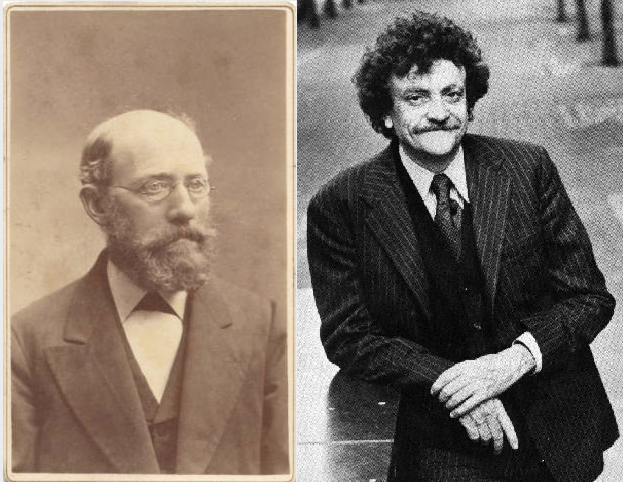

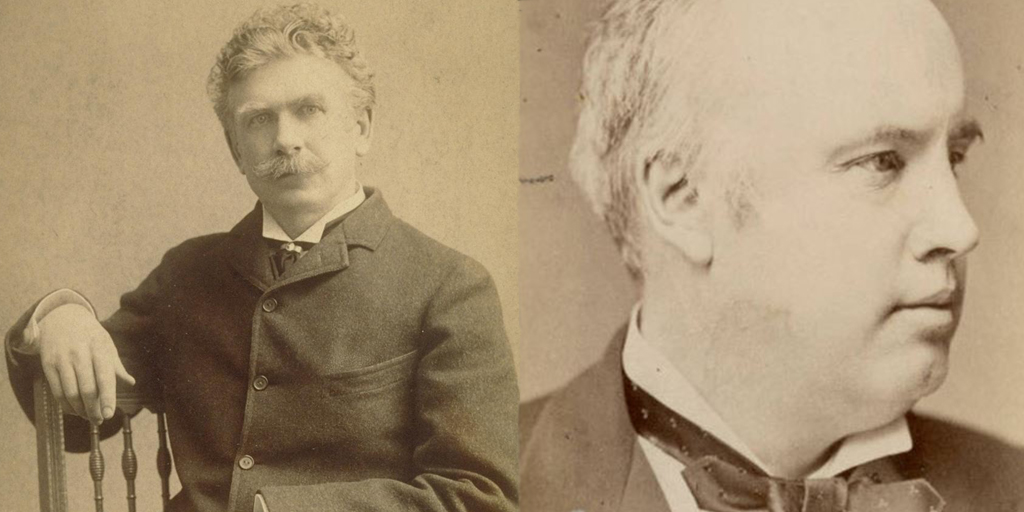

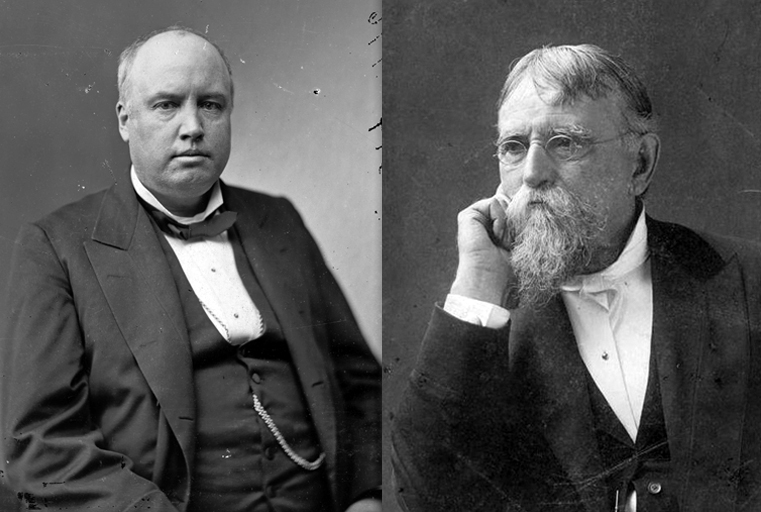

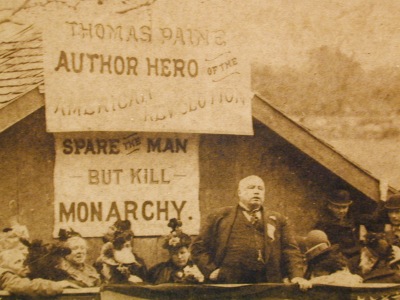

Robert Green Ingersoll (1833-1899) remains one of the most influential leaders and intellectuals in “The Golden Age of Freethought” in the United States from the 1870s to the 1910s. Its adherents advocated for skepticism, science, and the separation of church and state. Ingersoll, a Civil War veteran, parlayed his success as a lawyer into an influential career in Republican politics, social activism, and oratory. Ingersoll served as a counterpoint to rising participation and influence in government of religion in the United States, delivering speeches to sell-out crowds that decried religiosity and its public entanglements. Ingersoll was also an early champion of women’s rights, influencing such early feminists as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and later ones such as Margaret Sanger.

He also spent considerable time and energy in Indiana, a state whose own religious diversity towards the late nineteenth century expanded, including German Lutherans to Catholics and other protestant denominations. From giving lectures throughout the state to influencing some of Indiana’s well-known historic figures, Ingersoll left a profound impact on the state and its development during the Gilded Age. As an example, Ingersoll delivered lectures at the illustrious English’s Opera House several times. The Indianapolis News wrote in 1899 that his lecture on “Superstition” was well attended and that “several people were shocked by the lecturer’s utterances, and left, some of them stopping in the lobby to ‘talk it over.’ The remainder seemed to enjoy the walk.”

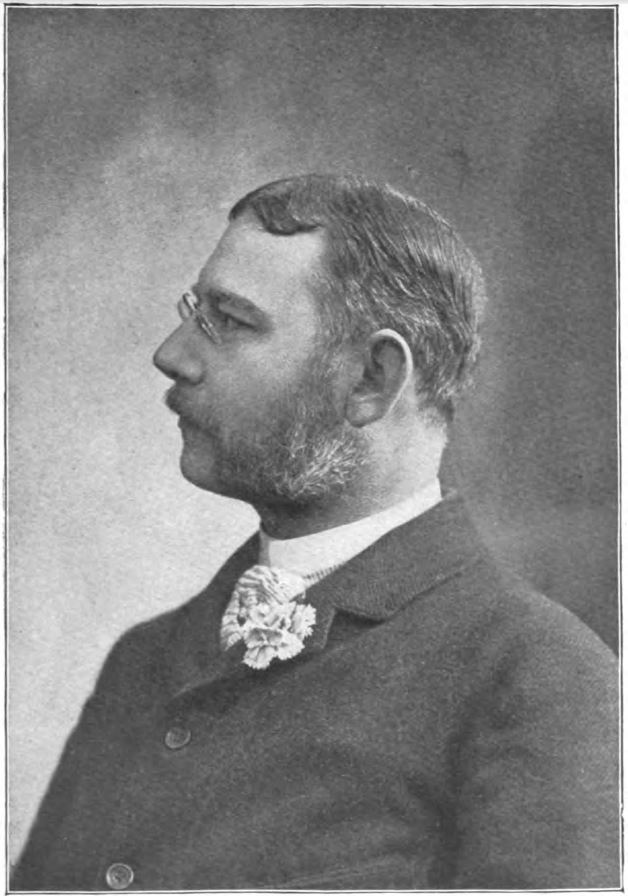

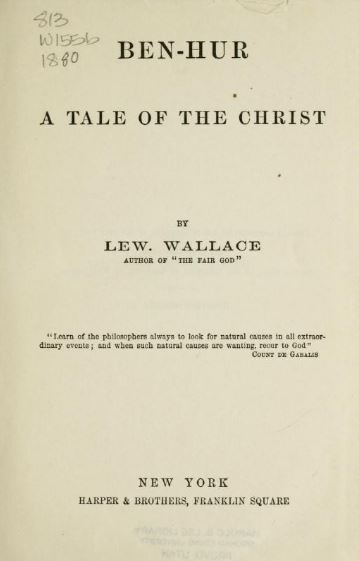

To get a further sense of this influence, one particular story bears recalling, which involved a train ride with an old Civil War colleague. Lew Wallace, Indiana native, Civil War general, and the author of the novel Ben-Hur, cited Ingersoll as his influence in writing the Christian epic. As Wallace biographers Robert and Katharine Morsberger noted, Wallace “had written the story [Ben-Hur] partly to refute Robert G. Ingersoll’s agnosticism. . . .” The story surrounding this influence is near apocryphal to scholars of both Ingersoll and Wallace. However, Wallace intimated the story’s veracity in the preface to a selection from Ben-Hur entitled The First Christmas.

On September 19, 1876, both Wallace and Ingersoll supposedly shared a train ride to Indianapolis to attend a Civil War soldiers’ reunion (although one of Wallace’s accounts says it was a Republican convention); both men served the Union Army during the Civil War and fought at the battle of Shiloh. Wallace recounted the highlights of their conversation in his preface to The First Christmas:

[I] took a sleeper [car] from Crawfordsville the evening before the meeting. Moving slowly down the aisle of the car, talking with some friends, I passed the state-room. There was a knock on the door from the inside, and some one [sic] called my name. Upon answer, the door opened, and I saw Colonel Robert G. Ingersoll looking comfortable as might be considering the sultry weather.

Ingersoll invited Wallace to join him in conversation. Wallace accepted on the condition that he could dictate the subject. From there, Wallace asked Ingersoll if he believed in the afterlife, the divinity of Christ, and the existence of God, with the “Great Agnostic” answering in the resounding, “I don’t know, do you?” Then, Wallace asked Ingersoll to present his best case against the doctrines of Christianity, which Ingersoll did with such “a melody of argument, eloquence, wit, satire, audacity, irreverence, poetry, brilliant antitheses, and pungent excoriation [concerning] believers in God. . . .” Ingersoll’s views of both theological and biblical skepticism shook Wallace to the core, with the latter remarking that, “I was in a confusion of mind unlike dazement.”

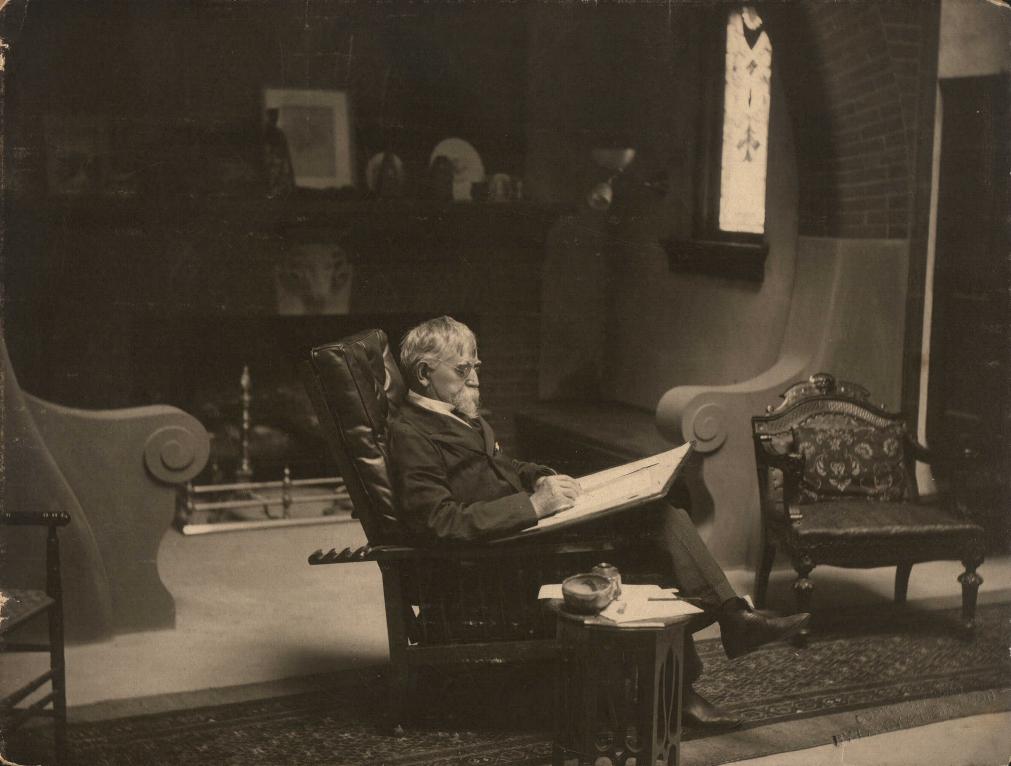

Lew Wallace’s own theological confusion, what he called “absolute indifference,” seemed spurred into action by Ingersoll’s words: “. . . as I walked into the cool darkness, I was aroused for the first time in my life to the importance of religion.” Thus, Wallace began his own investigation into the doctrines and traditions of Christianity, culminating in the authorship of Ben-Hur and a “conviction amounting to absolute belief in God and the divinity of Christ.” This story found its way into newspapers as well, with reporters recounting the meeting in the Terre Haute Sunday Evening Mail and the Indianapolis News. According to Wallace’s accounts and its echoes in newspapers, his evening with Ingersoll led to a full conversion to Christianity and the writing of one of the most successful religious novels of the period.

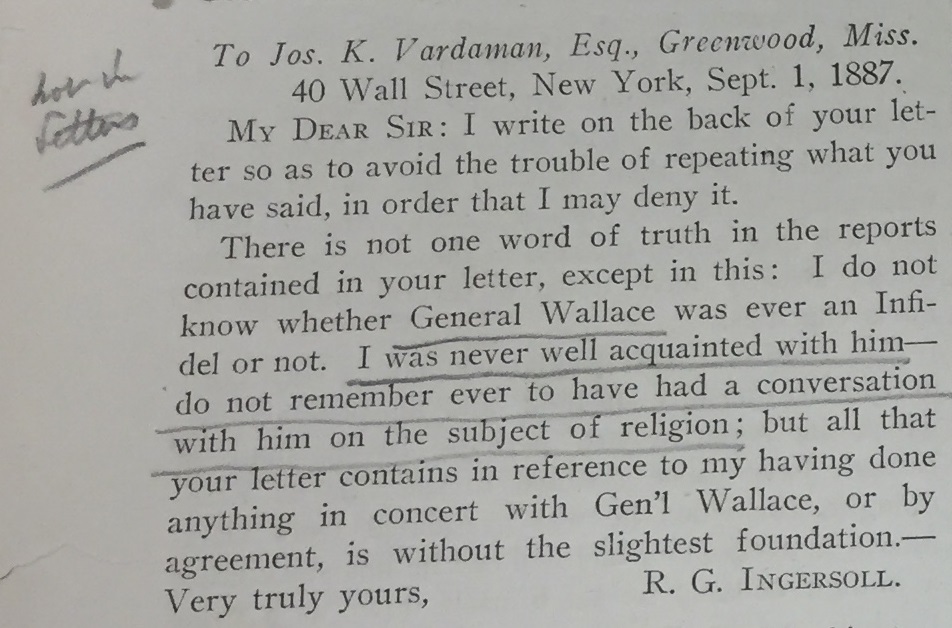

Wallace’s conversation with Ingersoll spurring him on to a religious awakening is indeed a compelling story. However, a recently uncovered letter from Ingersoll gives cause to question the tale’s veracity. In 1887, seven years after Ben-Hur‘s publication, Ingersoll responded to a correspondent, lawyer and future Mississippi Governor James K. Vardaman (incorrectly transcribed as Joseph Vardaman), asking about his role in inspiring Wallace’s novel. Ingersoll wrote that he was “never well acquainted with” Wallace and did “not remember ever to have had a conversation with him on the subject of religion.” Ingersoll stressed that the story of their meeting on the train appeared to him as “without the slightest foundation.”

For Wallace’s part in creating Ben-Hur, we know from documentary evidence that he was already well-advanced in writing the novel before the time he claimed the interaction with Ingersoll took place. In 1874, Wallace wrote in a letter to his half-sister, “I have just come out of the court room, and business is over for the day. Now, for home, and a Jewish boy whom I have got into terrible trouble, and must get out of it as best I can.” This letter clearly alludes to some of Judah Ben-Hur’s trials, whether being charged with the assassination of Valerius Gratus, being enslaved in a Roman galley, or surviving the sea battle.

While Wallace’s recollections with the “Great Agnostic” may have been a fiction, the story’s enduring popularity among Wallace scholars nevertheless speaks to Ingersoll’s intellectual and rhetorical power. The story of their supposed train ride in 1876 continues to interest scholars and the general public, but whether the event actually happened may be lost to history.