It is easy to assume that women unanimously supported woman’s suffrage, while men, clinging to their role as the households’ sole political actor, opposed it. However, this was not the case. In 1914, suffrage leader Alice Stone Blackwell wrote, “the struggle has never been a fight of woman against man, but always of broad-minded men and women on the one side against narrow-minded men and women on the other.”[i]

With the centennial of women’s suffrage upon us, we celebrate the determination of those women who fought for so long to secure their own enfranchisement. Understandably, many examinations of the suffrage movement only briefly touch on organized opposition of the movement, if at all. This is likely because it is much easier for us to identify with suffragists than it is with their counterparts. However, this lack of coverage can lead to the assumption that the anti-suffrage movement was weak or inconsequential compared to that of the pro-suffrage masses. That assumption would be incorrect. According to Historian Joe C. Miller, organized anti-suffragists outnumbered organized pro-suffragists until 1915, just five years before the ratification of the 19th Amendment. [ii]

In the wake of suffrage gains in western states, anti-suffragists began to organize in 1895, forming the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women. Later, women formed similar organizations in New York (1895) and Illinois (1906). In 1911, leaders within these groups came together to establish the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS), which led to increasing organization on a national scale. By 1916, when pro-suffragists finally outnumbered antis, NAOWS claimed to have organized resistance in 25 of the 48 states.[iii]

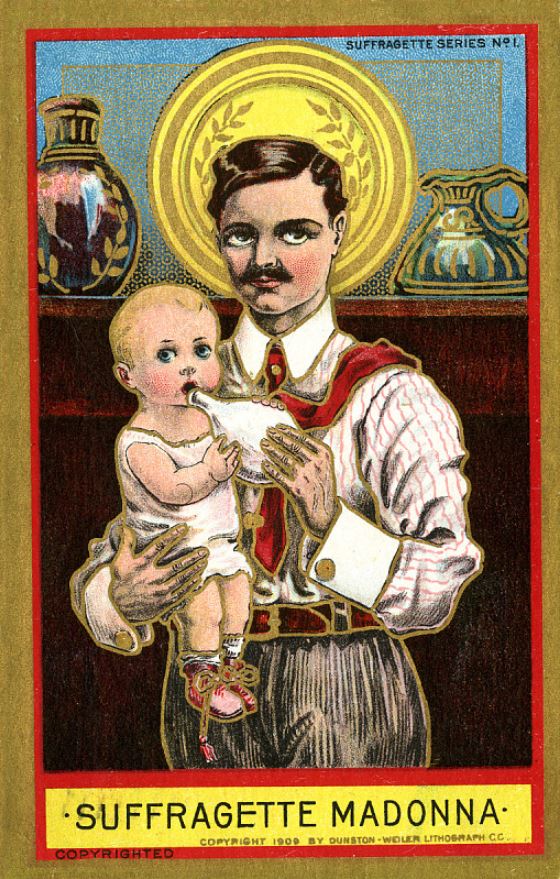

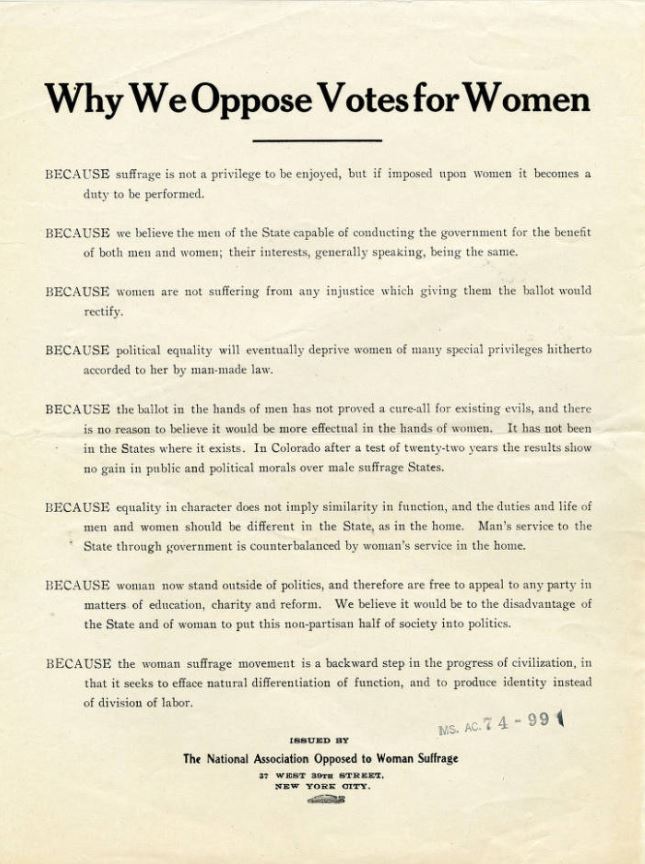

You may be wondering why so many women felt strongly about legislation that we would consider to go against their best interests. That’s a difficult question to answer since, as with any movement, each woman would have had her own reasons to oppose suffrage. The various pamphlets and broadsides distributed by NAOWS, such as the one below, shed light on their reasoning.

Views like those expressed in “Why We Oppose Votes for Women” became even more pervasive throughout 1916 and 1917 in response to a national spike of suffrage activity across the nation.[iv] Some Indiana women belonged to this opposition movement. Hoosier suffragists were working tirelessly to promote three separate bills that could lead to their enfranchisement. In the midst of the 1917 legislative session, anti-suffragists made their appearance in the form of “The Remonstrance,” a petition sent to State Senator Dwight M. Kinder of Indianapolis.

This “Remonstrance,” presented to the Indiana General Assembly on January 19, 1917, and subsequently reprinted in Indianapolis newspapers, laid out arguments against suffrage in three broad strokes:

- We Believe it is the demand of a minority of the women of our state.

- We are opposed to woman suffrage because we believe that women can best serve their state and community by leaving party politics to man and directing their gifts along the lines largely denied to men because of their obligations involved in the necessary machinery of political suffrage.

- We believe that with women in party politics there will arise a new party machine with the woman boss in control.

While these are the core arguments presented in the petition, it’s worth reading it in its entirety, as the supporting statements are fascinating. The petition’s arguments are similar to some of those put forth by the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, and there is a reason for that. On January 13, the Indianapolis News reported that anti-suffragists from Boston had been in the city for two weeks,

prepared to do a big and brave work. They went from house to house telling the poor misguided women of Indianapolis what a dreadful thing would befall them if they obtained equal suffrage. They asked that the women sign a petition against this particular brand of punishment the men of the legislature might mete out to them.

This was the same petition that would land on Senator Kinder’s desk days later. These East Coast anti-suffrage activists, either from the national organization or the closely-related Massachusetts group, came to Indiana, where no anti-suffrage organization existed, to turn women against their own enfranchisement.

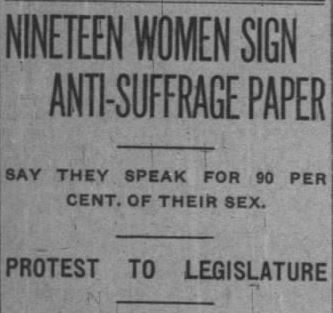

While this work did convince some Hoosier women to submit the petition, it wasn’t particularly successful—if anything, the petition generated more support than ever for the suffrage bills before the Indiana General Assembly. While the document claimed to represent the “great majority of women” in the state, it was signed by just nineteen women, all of whom lived in the same upper-class Indianapolis neighborhood and who would likely have traveled in the same social circles. The response from suffrage activists around the state was swift.

Just two days after “The Remonstrance” appeared in Indianapolis papers, the Indianapolis News published an article penned by Charity Dye, an Indianapolis educator, activist, and member of the Indiana Historical Commission (which eventually became the Indiana Historical Bureau). Responding to the antis’ claim that they represented ninety percent of Hoosier women, Dye released the results of a poll taken in the fall of 1916. The women polled were all residents of the Eighth Ward of Indianapolis and each woman could select from “pro,” “anti,” and “neutral,” options. Of 1,044 women polled, 628 (60%) were in favor of suffrage. Dye ends the article, “In view of the fact that nineteen Indianapolis women asserted in The News Saturday that 90 per cent of Indiana women are opposed to suffrage, this is interesting reading.”[v]

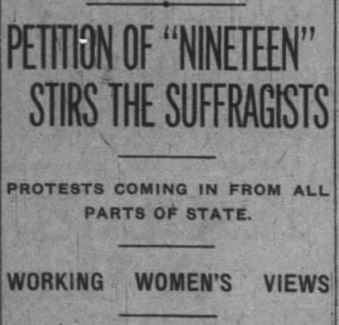

The next day, women from around the state began sending their own list of nineteen names to newspapers—all in favor of suffrage. First, nineteen librarians and stenographers declared their support for suffrage “for what it will mean to them in the business world.”[vi] Next came nineteen Vassar College graduates, who signed their names “in protest against the assertion of nineteen anti-suffragists that women do not want suffrage.”[vii] Finally, nineteen “professional women,” who held medical degrees added their names “just because it is right.”

As lists of names continued to pour in from around the state, Joint Resolution Number 2, which would have granted Hoosier women full suffrage if passed, was winding its way through the Indiana General Assembly session. Just as enthusiasm for the bill reached its zenith, a new, even more promising prospect appeared when the legislature enacted a Constitutional Convention bill on February 1. According to Historian Anita Morgan, “A new Indiana Constitution could have full suffrage included in the document and eliminate the need to rely on a state law that could be overturned.” Pro-suffrage support for the convention flooded in.

Anti-suffragists saw this as possibly their last chance to block the enfranchisement of women in Indiana and called for a legislative hearing, where they could voice to their grievances. Their goal was to persuade future members of the Constitutional Convention not to add women’s suffrage to the newly penned constitution. They got their hearing, but it didn’t exactly go as planned. On February 13, 1917, men and women, who supported and opposed suffrage, flooded the statehouse. What followed was hours of “speeches for and against votes for women [which] flashed humor, keen wit and an occasional bit of raillery or pungent sarcasm that brought laughter or stormy cheering.” First, state representatives heard from pro-suffragists, who pointed out that both the House and Senate had already expressed support for suffrage – all that was left now was to hammer out the details. The crowd, overwhelmingly composed of suffrage supporters, cheered throughout the address. Then Mary Ella Lyon Swift, leader of the original nineteen anti-suffrage remonstrants, spoke. She opined:

Suffrage, in my opinion, is one of the most serious menaces in the country today. With suffrage, you give the ballot to a large, unknown, untested class – terribly emotional and terribly unstable. . . If you thrust suffrage upon me you dissipate my usefulness, and in the same way you dissipate the usefulness of the most unselfish, most earnest and most capable women, who are working in their way, attracting no attention to themselves for the good of their country and mankind.

When one representative asked Swift to explain that last statement, she replied that suffrage would make “it necessary for us to fight the woman boss and the woman machine.”

There again appears that talking point from the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, that once women get the vote, they’ll be irrevocably corrupted, with all-female political machines being run by female political bosses. One of the only other female speakers opposing women’s suffrage was Minnie Bronson, the secretary of NAOWS. Bronson addressed the overwhelming presence of pro-suffragists, quipping, “[Anti-suffragists] are not here pestering or threatening you, but are at home caring for their children.” Finally, after hours of debating, Charles A. Bookwalter, former mayor of Indianapolis, delivered the decisive line, “It is 10:35 o’clock. Suffrage is right and hence inevitable.”[viii]

This hearing seems to have been the last gasp of the anti-suffrage movement in Indiana. While suffrage detractors continued to voice their opposition from time to time, the organized efforts of NAOWS in Indianapolis had come to an end. The nineteen women who sent “The Remonstrance” to the Indiana General Assembly went back to hosting parties, attending literary club meetings, doing charity work and, presumably, not exercising their newly-granted rights when the 19th amendment was ratified in 1920.

[i] Joe Miller, “Never a Fight of Woman Against Man: What Textbooks Don’t Say about Women’s Suffrage,” The History Teacher 48, no. 3 (May 2015): 437.

[ii] Ibid., 440.

[iii] Mrs. Arthur M. Dodge, “Keynote of Opposition to Votes for Women,” Boston Globe, October 15, 1916, 54, accessed Newspapers.com.

[iv] Dr. Anita Morgan, “We Must Be Fearless”: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Indiana (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press, 2020), p. 137-138.

[v] Charity Dye, “Gives Suffrage Vote for the Eighth Ward,” Indianapolis News, January 22, 1917, 22, accessed Newspapers.com.

[vi] “Petition of ‘Nineteen’ Stirs the Suffragists,” Indianapolis News, January 23, 1917, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.

[vii] “Protest of Vassar Women in Factor of Equal Suffrage,” Indianapolis News, January 24, 1917, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[viii] “Sparks Fly at Hearing for Women,” Indianapolis Star, February 14, 1917, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.