The results of a hotly challenged event, the first ever Women’s Safety Driving Contest made the front page of the August 12, 1923 Indianapolis Sunday Star. Sponsored by the newspaper and Indianapolis police department, the contest had drawn two hundred entrants. Competition proved fierce, with first place decided by a solitary point. Photos of the top eight “lady drivers” featured prominently, yet ten pages back, tucked between “Married Women Often Forget Maid Friends” and “Gotham Gossip About Hoosiers,” an event of arguably more significance would soon be taking place. The headline simply read: “Women Lawyers to Attend Convention.”

Fifty years before winning the right to vote in 1920, women began entering the legal profession. In 1899, a group of eighteen New York City women formed the Women Lawyers’ Club. Twenty-four years later, the newly-rechristened National Association of Women Lawyers planned to hold its first convention on August 28 – 29, 1923 in Minneapolis, with Chief Justice and former President William Howard Taft in attendance. The six Hoosier lawyers highlighted in the Star’s story would play key roles in moving women into positions of power and public leadership.

On October 7, 1894, the Sioux City Journal announced that “Miss Emma Eaton of Creston, Iowa, passed the examination at the head of the class.” The paper noted “She is a graduate of the state university [Iowa University] and the law department of Ann Arbor University [University of Michigan]. When her standing was announced, she was congratulated by the judges present and applauded by her classmates.”

Emma made a handful of court appearances in Iowa, assisting the Union County Attorney before settling on legal editorial work. In 1900, she married Edward Franklin White, a respected Indianapolis attorney and author. “Peggy” as she now called herself, was expected to put aside her professional career. For a few years she did just that, likely helping her husband edit law books. But in 1915, she got involved with a legislative bill to grant Indiana women partial suffrage; evidently not a universally popular position judging by the number of letters to the editor opposing it.

Historian Jill Weiss Simins noted that the two major state suffrage organizations—the Equal Suffrage Association (ESA) and the Woman’s Franchise League (WFL)—opposed one another regarding the question “Should suffragists accept partial suffrage to get their foot in the door and later work for full suffrage or demand full suffrage as their inalienable democratic right?” White toed the ESA’s line of thought in this regard. Responding to one particularly irate missive, White noted, “Some little independence of thought doesn’t hurt any cause.” That same year, White prepared arguments to the Indiana General Assembly for a bill to approve “the appointment of policewomen in twenty-five cities of the state.” Supporting her would be another entrant into Indiana’s legal profession, Eleanor P. Barker. Through their work, Indiana became one of the first to inaugurate a statewide system of policewomen. When “the policewoman bill” introduced by Robert W. McClaskey failed in 1915, she used her involvement in the Women’s Legislative Council of Indiana to pressure lawmakers to revisit it.

While membership in the Women Lawyers’ Club had grown to 170 members by 1914, locally two women would graduate from the Indiana Law School, one of them being Barker. The Indianapolis trailblazer became the first woman to win highest honors from any Indiana law school and the only woman to accomplish that particular feat two years in succession.

Like White, Barker dedicated herself to the cause of women’s enfranchisement. However, she toed the WFL’s line and felt it couldn’t be achieved on a state-by-state basis, opining that partial suffrage “took the steam out of the suffrage movement.” Instead, she supported the Anthony Amendment, which would become the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. Along with her role as the Indiana standard-bearer in Washington, D.C. suffrage parades, Barker chose to picket the White House “to impress President (sic) Wilson with the vigor of the militant suffrage crusade.” She also traveled the state registering women to vote and giving free classes in civics and political science.

Like many suffragists, Barker committed to war work at the outbreak of the Great War. Dr. Anita Morgan noted in her “We Must Be Fearless:” The Woman Suffrage Movement in Indiana that “What the war managed to do was to finally focus the energies of all these suffragists and clubwomen, so they acted in concert for one goal—win the war and in the process win suffrage for themselves.” The February 24, 1918 issue of the Indianapolis Star reported on Barker’s work, noting “In a time of below-zero weather, stalled traffic, all but impassable roads and multiplied discomforts and difficulties she heroically kept on her schedule made by the 14 – Minute Women’s Speaker’s Bureau.” As head of the state’s Congressional Union/Woman’s Party, Barker delivered thirty-two speeches, fourteen minutes long of course, about food substitution and conservation to record crowds throughout the Midwest. She also led the Women in Industry Committee, advocating for women’s and children’s working conditions during the war.

Ella Groninger was the second graduate from the class of 1914 and joined the family law firm of Groninger, Groninger & Groninger. A native of Camden, Ella had taught school before moving to Indianapolis in 1900. There, she attended the East Business College, clerking at her brothers’ law firm before obtaining her law degree. On October 15, 1919, in Marion County Superior Court, room five, Ella M. Groninger became the first woman judge to preside in an Indiana courtroom, ruling on the Tenney v. Tenney case.

George Tenney arrived with a litany of grievances in his divorce petition against Ida M. Tenney, claiming his wife hadn’t sewed buttons on his clothes and left the house lights on when she went out at night. After careful consideration, Special Judge Groninger denied the petition, saying “From the evidence introduced here, this woman has given twenty-nine of the best years of her life to this man. There is no proof of wrong.” When questioned afterwards on her decision, Groninger remarked, “The double standard of morality should not be given a chance to grow out of our divorce courts.

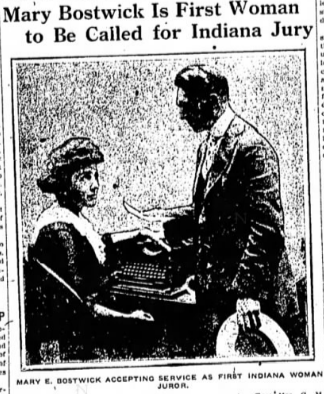

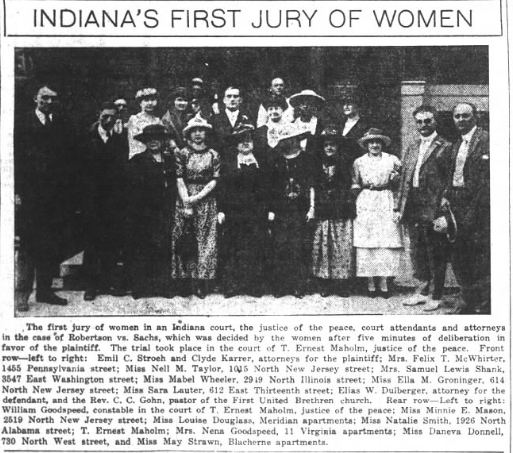

Groninger was judge and jury, serving on the first jury of women in an Indiana court, made possible by ratification of the 19th Amendment. The case, a replevin suit for the recovery of a Victrola, took place in the court of T. Ernest Maholm, Justice of the Peace, on August 28, 1920. Although the trial was scheduled to start at nine o’clock, Mary E. Boatwick, the first Indiana woman to be served with a jury summons, had to be excused due to pressing matters related to her work for the Indianapolis Star. A half hour later, twelve women were sworn in to a courtroom, which was decorated with a “bank of flowers” arranged around dusty law books in honor of the historic occasion. The women represented a variety of religions, races, and professions, and included African American suffragist and actuary Daneva Donnell.

Although Gronginger was listed as the only attorney, juror M. Elizabeth Mason had begun her final year at Benjamin Harrison Law School. Born in Ohio, she had attended the University of Chicago before relocating to teach at Indianapolis public schools in 1904. At the age of forty-four, she decided on a legal career, taking classes at night. The following year, “Minnie” Mason became one of three exceptional women to earn a degree from Hoosier law schools.

The defense’s strategy, noted by the Indianapolis Star, was unique: “Louis Dulberger, in a snappy gray suit and white suede shoes, smilingly told the jury how he had ‘long awaited to see the time when women could sit on the jury in the court, and, now that the time has come, insisted that only women serve on the jury in this case.’” His platitudes did little to sway the jurors, who deliberated for five minutes before forewoman, Groninger, announced they’d reached a verdict—in favor of the plaintiff. As they filed out of the courtroom, the jurors were given a white chrysanthemum as a memento from the historic day.

Following Mason was Adele Storck, who became the second woman to graduate from Benjamin Harrison Law School in 1921, winning top honors for the best senior class thesis. Born in Kassel, Germany, Adele Storck immigrated with her family to Odell, Illinois. In 1900, similar to her friend, Mason, she took a teaching position within the Indianapolis public school system. Later, she attended DePauw University before entering law school at the age of forty-five.

After graduation, Storck became the first woman admitted to the Indianapolis Bar Association. She and her friend established Storck & Mason, credited as “the first woman’s law firm in Indiana” and one of the earliest in the country. On October 21, 1921, in one of the fledgling partnership’s first cases, Storck & Mason filed suit for the plaintiff, Hattie A. Storck, Adele’s sister in Marion County Circuit court. The outcome has been lost to history, but the law firm of Storck & Mason continued on for well over three decades with both partners considered “pioneer women attorneys.”

Officially, the law firm of Stork and Mason ended upon the death of “Minnie” Mason in 1955. Over the years, it had stood as a sterling example of equality, setting the stage for the emergence of numerous women-owned business nearly five decades later. Of equal note, Mason and Storck showed that it’s never too late in life to pursue your dreams.

The final woman from our group of trailblazers benefited from the others’ experience. Graduating in 1921 from the Indiana Law School, Jessie Levy eschewed the expected career “in estate planning, probate, and related tax matters,” instead gravitating towards criminal law. Her clientele included four members of the John Dillinger gang. Accused of trying to throw open “the doors of freedom to the most notorious public enemies in the Midwest,” Levy replied that her only interest was in obtaining a “fair trial,” but added, “When the time comes and I am challenged, I will have plenty to say.”

And that she did, becoming in May 1934, the first woman from Indiana admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Court. A month later, Levy became the first woman to deliver a stay of execution in Ohio. Reflecting back, she observed, “Oh, I had some pretty lurid cases in my time but I enjoyed what I was doing and found the cases challenging.” On February 1, 1951, a bill sat pending in the Indiana General Assembly with a clause allowing a husband to sell jointly-owned property without the signature of his wife. Contending that the proposed bill would make it easier for one spouse to cheat the other, Levy led a referendum for an amendment requiring the signatures of both spouses.

In 1971, after a half century practicing law and presiding over every Marion County court as either a special judge or judge pro tem, Levy would be honored by the Indianapolis Bar Association. When an Indianapolis Star reporter observed that fifty years in practice qualified her as a senior citizen, Jessie protested, “But I still feel young,” and then excused herself for a scheduled court appearance.

These six exceptional women epitomized the advice given by the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who in 2015 told a group of young women at Harvard University: “Fight for the things that you care about, but do it in a way that will lead others to join you.” While the 19th Amendment increased women’s agency, it did not eliminate discrimination against them. Women still had to navigate a maze of state laws meant to keep them from exercising their rights. This is where the six Hoosier women made their most lasting contributions; each opposed discriminatory practices and laws restricting women’s access to the courtroom and the office. In the 1926 words of Eleanor P. Barker, “Women in Indiana have done more for politics and received less at the hands of politicians than the women of any other state.”

Click here for other firsts accomplished by these attorneys and a list of further reading sources.