Editor’s note: Read this, but don’t forget to check out our podcast about Garrett too!

In 1947, Jackie Robinson made history when he broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball. Robinson set the precedent, and in the years following, many African American players would follow his lead to join big league teams. In 1948, just one year after Robinson’s debut with the Dodgers, Indiana witnessed its own trailblazer in sports, as Shelbyville’s Bill Garrett broke the ironically named “gentleman’s agreement” that had barred African Americans from playing Big Ten college basketball (the Big Ten became the Big Nine in 1946 when the University of Chicago withdrew its membership. In 1949, Michigan State College – now Michigan State University – joined the conference, and it again assumed the name the Big Ten).

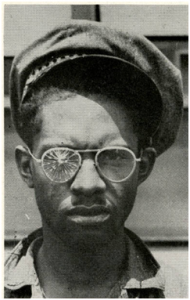

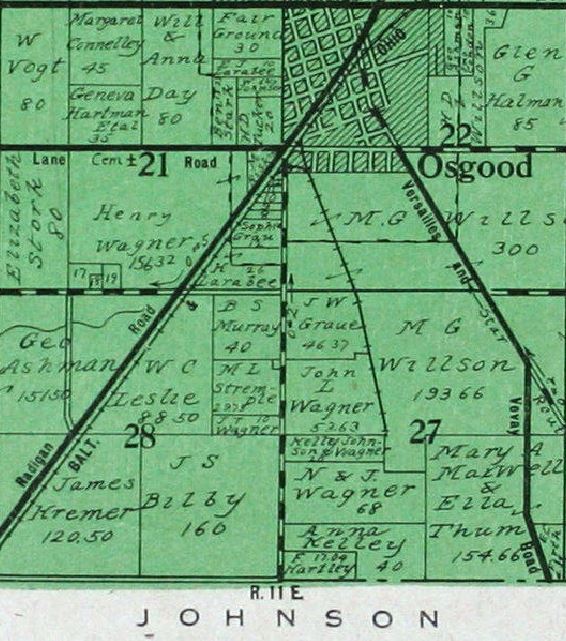

Bill Garrett was born in 1929, at a time when segregation and racial discrimination were rampant in Indiana. The Indianapolis Times had just been awarded the Pulitzer Prize for exposing the Ku Klux Klan’s influence in state politics the year before, and just one year later the state would experience the horrific lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion. In their thoroughly researched book Getting Open: The Unknown Story of Bill Garrett and the Integration of College Basketball, authors Tom Graham and Rachel Graham Cody note that Shelbyville avoided much of the racial violence that other Indiana communities experienced at this time, but that segregation was nevertheless commonplace. Garrett, like other African Americans there, attended the segregated Booker T. Washington Elementary School, and when he entered Shelbyville High School in the 1940s, he was one of only a few black students in his class.

Despite this, Garrett became widely recognized for his skills on the basketball court, and by his senior year in high school (1946-1947), he was one of the star players on Shelbyville’s varsity basketball team. Newspapers across the state praised him for his play. On January 9, 1947, one day after Garrett helped lead the Shelbyville Golden Bears to a decisive 59-40 victory over Greencastle, the Greencastle Daily Banner recognized him as “one of the smoothest performers and best shots” to appear on the Greencastle court over the years. He was quick, clever, and had a “natural talent” for the game. Many regarded him as the second Johnny Wilson. Wilson, also African American, had graduated the year before from Anderson High School, where he led the team to the state basketball title and was named Indiana’s “Mr. Basketball.” The Indianapolis Recorder noted the similarities between the two in a March 22, 1947 article, stating that the resemblance in their play was “uncanny.”

The mark of greatness, however, in Garrett as in Wilson, is the ability to sweep through the opposition and turn a stalemated contest into a rout. It is that extra speed and split-second timing which stamps an all-state player as distinguished from a good player. It is cool floor-generalship and flawless ball-handling – and Garrett has them all.

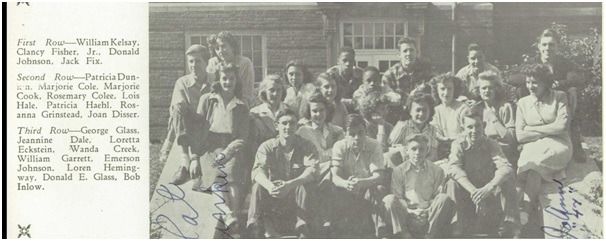

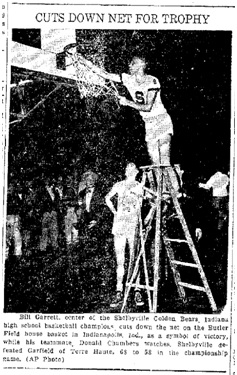

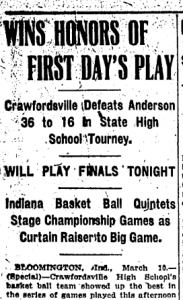

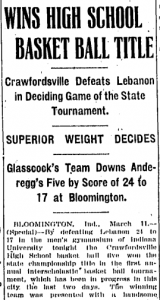

When the 1947 Indiana high school basketball tournament kicked off in late February that year, 781 teams competed for a shot at the title. Despite the odds, Garrett, along with starters Emerson Johnson, Marshall Murray, Hank Hemingway, and Bill Breck, helped lead Shelbyville to the school’s first basketball championship. On March 22, Shelbyville defeated the East Chicago Washington Senators 54-46 and advanced to the title game where they beat undefeated Terre Haute Garfield 68-58.

At a time when segregation was prevalent in the state, Shelbyville’s team featured three African American starters: Murray, Johnson, and Garrett, each of whom had captured the hearts of Shelbyville fans.

Garrett had set a new individual state tournament scoring record during the competition. His 91 points in the final four games broke the 85-point record set by Johnny Wilson the year before. And like Wilson, he too was named “Mr. Basketball” for the season.

After the 1947 title game, many wondered where Garrett would continue his basketball career. Despite the fact that he, Wilson, and other African American players were leading their teams to high school titles and were considered some of the best players in the state, the “gentleman’s agreement” barred them from playing college basketball on Big Ten varsity teams into the late 1940s. Reports out of Indiana University at this time note that there was “no written rule in the Big Ten regarding participation in athletics. The unwritten rule subscribed to by all schools precludes colored boys from participating in basketball, swimming, and wrestling.”

In the years following, many would question the inconsistency of this rule, as blacks participated in football and other Big Ten sports during this period. Some speculated that the reason for the discrepancy was that basketball was played in more intimate settings with briefer uniforms, thus increasing the chance of contact between white players’ and black players’ skin.

Referred to as the” gentleman’s agreement,” the “unwritten rule,” or the “lily-white rule,” the color line in basketball came under increasing attack throughout the 1940s as more and more talented black players were being overlooked solely because of their race. In 1944, African American Richard (Dick) Culbertson played varsity at the University of Iowa, but coaches largely regarded his participation as an exception rather than the rule. Culbertson was a substitute rather than a starter, and wartime conditions had made it more difficult to field a team, leading to slightly relaxed rules.

On March 25, 1947, after watching Bill Garrett, Emerson Johnson, and Marshall Murray help Shelbyville win the state championship, John Whitaker of the Hammond Times wrote an open letter to the commissioner of the Big Ten in which he asked why the “unwritten agreement” existed:

If the biggest, braggingest athletic conference in the middle of the greatest country in the world can use Negroes like Buddy Young, Ike Owen, Dallas Ward, Duke Slater, George Taliaferro and the like to draw $200,000 crowds for football . . . and Negroes like Jesse Owen[s] and Eddie Tolan to win Olympic crowns . . . why can’t it use them in basketball.

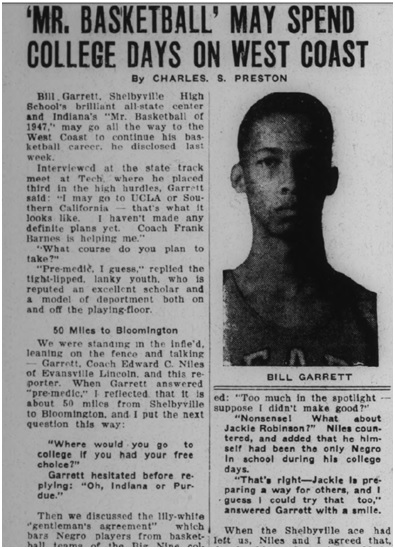

In June 1947, the Indianapolis Recorder reported that despite Garrett’s hopes to play Big Ten basketball at IU or Purdue, the “gentleman’s agreement” might force him to continue his career in California. The news disappointed many who had hoped to see Garrett stay in state, and prompted Recorder writer Charles S. Preston to call out the state and the Big Ten conference in hopes of bringing an end to the ban:

What in Hades is the matter with the Hoosier state, when we are going to let one of our best basketball players of all time get away from us, and go out to California to play! And all because of a ridiculous ‘unwritten law’ that doesn’t begin to make sense!

Though some denied that such an agreement barring blacks from Big Ten basketball existed, the continued absence of African Americans on these teams indicated otherwise.

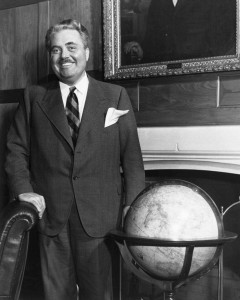

Fearful that Garrett would be bypassed by Big Ten teams like others before him, black leaders in Indianapolis banded together in order to persuade IU to give him an opportunity to make the school’s team. Faburn DeFrantz, Executive Director of the Senate Avenue YMCA in Indianapolis, spearheaded the effort, and in the months following the 1947 state high school tournament, he and other black leaders drove down to Bloomington to meet with IU President Herman B Wells on Garrett’s behalf.

President Wells was eager to end racial discrimination and segregation at IU, and had already been doing so quietly in other parts of the campus at this time. After meeting with DeFrantz and the others, Wells asked IU basketball coach Branch McCracken to give Garrett a chance to make the team, noting that he would handle any potential backlash from other Big Ten coaches.

In DeFrantz’s unpublished autobiography, excerpts of which were obtained by Graham and Cody during their research, DeFrantz acknowledges Wells’ role in helping to break down racial barriers at IU:

In Indiana University’s President Herman B Wells democracy found an ally. No overhaul of policy such as that accomplished at Indiana University could have been possible without the cooperation he gave.

In an October 4, 1947 article, the Indianapolis Recorder praised DeFrantz and others for their efforts to get Garrett to IU and recognized them as “key figures in the victory for democracy.” In January 1949, during Garrett’s first season on the varsity team, the Recorder named DeFrantz to its 1948 Race Relations Honor Roll, noting his unremitting campaign to help end racial discrimination in sports. Two years later, Garrett would also be named to this Honor Roll.

Garrett was admitted to IU in the fall of 1947 and played one year on the freshman basketball squad. He made his regular-season varsity debut in December 1948 as IU beat DePauw 61-48. In doing so, he became the first African American player on an IU varsity basketball team. More importantly, the Recorder recognized on December 11, 1948, that “Garrett’s entry into the Big Nine ranks may prove to be the beginning of the end for an anti-Negro ‘gentleman’s agreement’. . .”

Integration in basketball, both at the high school and eventually the college level went a long way in improving race relations in the state, as fans cheered their teams to victory regardless of the color of their players’ skin. On February 18, 1950, the Recorder reported on the influence that sports had on blurring the color line, stating:

Race prejudice, too, has generally been given the bum’s rush by the fans who lose sight of everything but the fortunes of OUR TEAM. The performances of such athletes as Bill Garrett, Johnny Wilson, and a host of others have probably done as much as anything else to kill the Ku Klux Klan spirit in Indiana. A quick field goal by a Negro player will do more to “convert” the ordinary Hoosier than all the Race Relations Days in a century.

Garrett helped “convert” thousands in Shelbyville and across the state during his high school years and he would work to do the same while playing at IU.

Check out Part II coming later this week to learn about Garrett’s achievements while on IU’s squad, his impact on other African-American players, and his career after graduating.

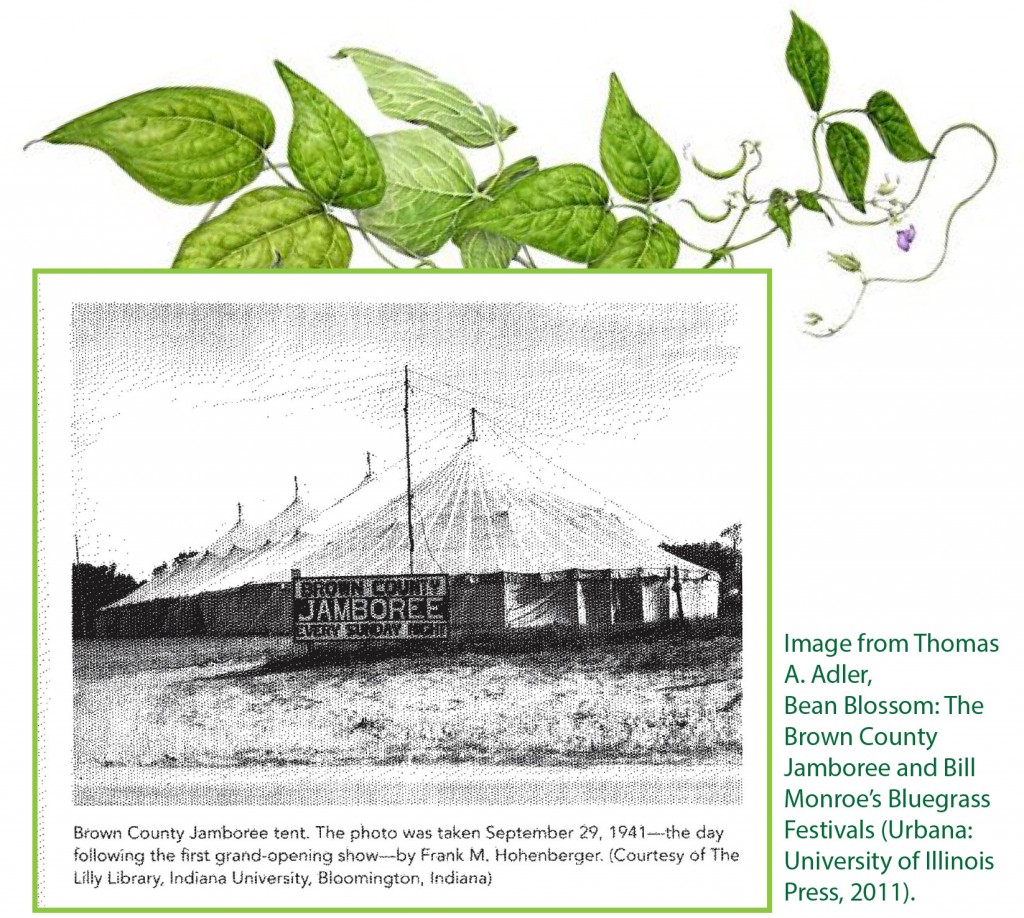

The “free” aspect of the free show didn’t last long, as the organizers couldn’t help but see how the crowd was growing. The lunchroom business was booming and there was no reason the promoters and performers shouldn’t make a little money too. They built a small stage, fenced in the area, and started to charge twenty five cents per show. Soon, they put up a tent as can be seen in the only known photograph of the Jamboree from this period.

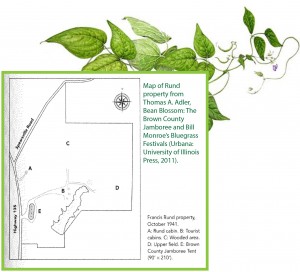

The “free” aspect of the free show didn’t last long, as the organizers couldn’t help but see how the crowd was growing. The lunchroom business was booming and there was no reason the promoters and performers shouldn’t make a little money too. They built a small stage, fenced in the area, and started to charge twenty five cents per show. Soon, they put up a tent as can be seen in the only known photograph of the Jamboree from this period. Just before the Jamboree launched, locals Francis and Mae Rund had been making improvements to their nearby property and building cabins with some sort of tourism-related business in mind as early as August 1940. By the summer of 1941, as the large crowds coming to the Jamboree were causing traffic and parking problems and more seating was needed at the outdoor venue, the Runds saw an opportunity to construct a permanent building (as opposed to a tent) so the programs could continue be held in the winter. Construction began in October. The barn-like building was funded by residents and was to seat 2,500 attendees. On October 23, 1941, the Brown County Democrat reported:

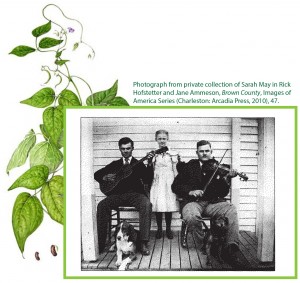

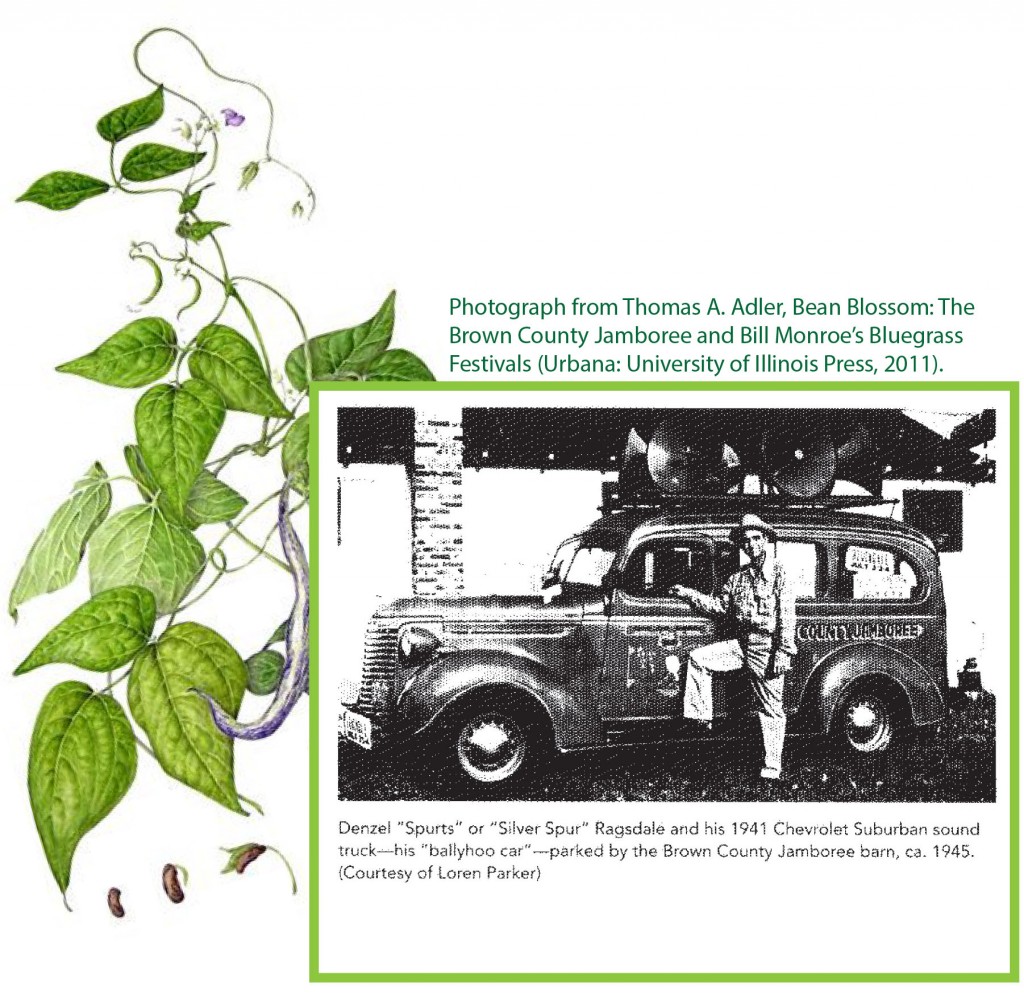

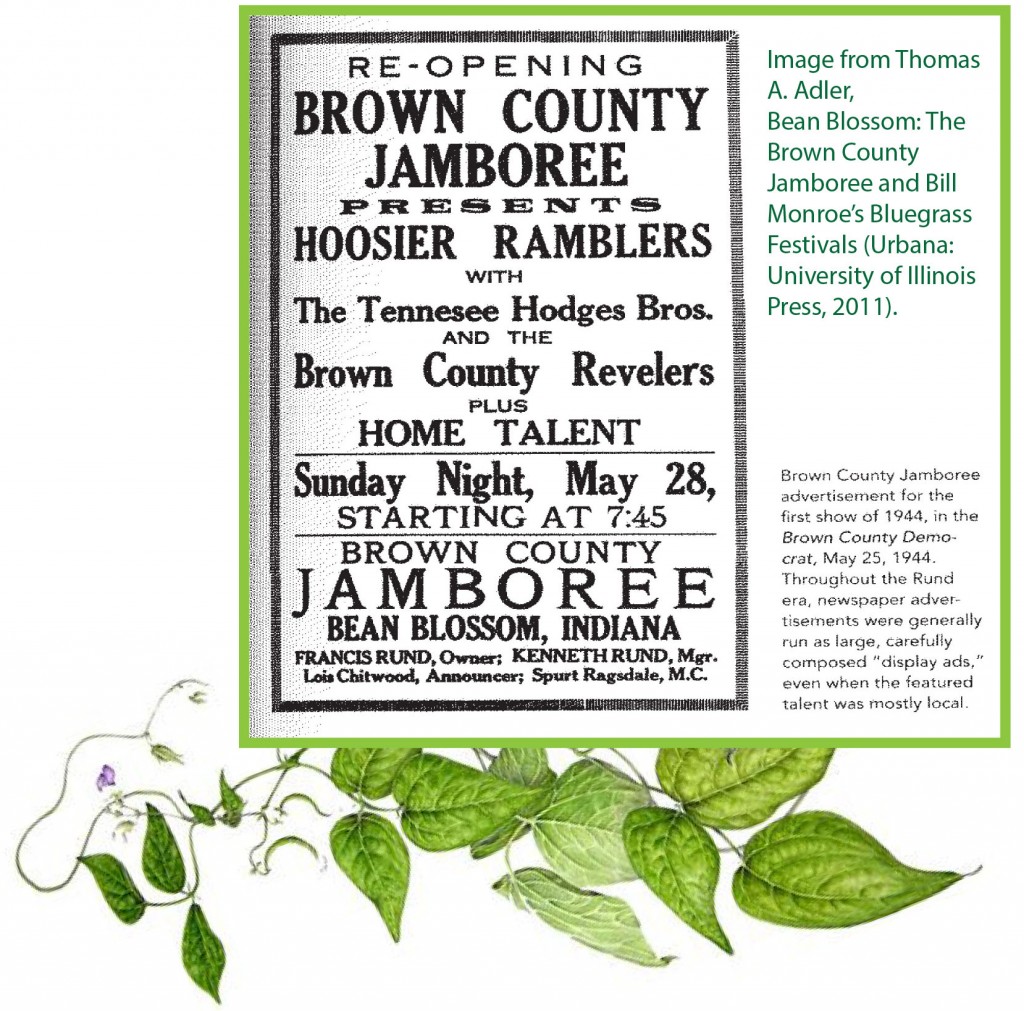

Just before the Jamboree launched, locals Francis and Mae Rund had been making improvements to their nearby property and building cabins with some sort of tourism-related business in mind as early as August 1940. By the summer of 1941, as the large crowds coming to the Jamboree were causing traffic and parking problems and more seating was needed at the outdoor venue, the Runds saw an opportunity to construct a permanent building (as opposed to a tent) so the programs could continue be held in the winter. Construction began in October. The barn-like building was funded by residents and was to seat 2,500 attendees. On October 23, 1941, the Brown County Democrat reported: The shows during the Rund decade (1941-51) generally featured a variety show format hosted by an emcee which included comedic performers as well as music. However, the country and “hillbilly” music was always the main draw. Adler writes, “Brown County Jamboree shows were professional, fast paced, and entertaining. From the beginning, the music, comedy, and ambience of the site combined to present a nostalgic and entertaining whole.” The Indianapolis Star on August 10, 1941 described the Jamboree as “a co-operative program providing real, homespun talent, rail-fence variety of music and frivolity . . . old fiddlers and rural crooners, who would sing and warble Brown county ballads brought over the mountains by their pioneer ancestors.” The Indianapolis Times noted October 10, 1941 that in addition to “singing and dancing” the Jamboree included “vaudeville skits.” The Runds ran large advertisements for the Jamboree in the local newspaper and partnered with nearby radio stations, notably WIRE and WFBM, Indianapolis. On October 23, 1941, the Brown County Democrat reported that the Indianapolis radio station WIRE referenced the Jamboree many times during its programs.

The shows during the Rund decade (1941-51) generally featured a variety show format hosted by an emcee which included comedic performers as well as music. However, the country and “hillbilly” music was always the main draw. Adler writes, “Brown County Jamboree shows were professional, fast paced, and entertaining. From the beginning, the music, comedy, and ambience of the site combined to present a nostalgic and entertaining whole.” The Indianapolis Star on August 10, 1941 described the Jamboree as “a co-operative program providing real, homespun talent, rail-fence variety of music and frivolity . . . old fiddlers and rural crooners, who would sing and warble Brown county ballads brought over the mountains by their pioneer ancestors.” The Indianapolis Times noted October 10, 1941 that in addition to “singing and dancing” the Jamboree included “vaudeville skits.” The Runds ran large advertisements for the Jamboree in the local newspaper and partnered with nearby radio stations, notably WIRE and WFBM, Indianapolis. On October 23, 1941, the Brown County Democrat reported that the Indianapolis radio station WIRE referenced the Jamboree many times during its programs.