Sometimes when you think back over your old history texts, and remember that the accounts there relate the deeds of men- not women- doesn’t it give you a marvelous feeling to realize that the greatest chapter of history of mankind is being written today, and that you women are going to have your names in the headlines?

-LaVerne Heady, columnist for Republic Aviation News

Reliable, versatile, and fast, the P-47 Thunderbolt is considered one of the most important fighter-bombers in World War II. Manufactured by Republic Aviation Corporation and debuted in 1943, the P-47 served in both the European and Pacific theaters and quickly became the Allied Forces’ main workhorse. By the end of the war, Republic Aviation produced 15,683 Thunderbolts, which performed more than half a million missions, shooting down more Luftwaffe aircrafts than any other Allied fighter. What’s more impressive than its statistics, however, is the pilots’ testimonials on the durability of these planes, which quickly gained a reputation for their ability to deliver a pilot safely home after sustaining otherwise catastrophic amounts of damage.[i] One of the most dramatic examples of the Thunderbolts’ durability occurred in 1945, when the entirety of a P-47s right wing was sheared off during a bombing mission. The pilot returned to base unharmed, and the plane was reportedly repaired and flown for another 50 missions.[ii]

Military history often focuses on aircraft design and the pilots who flew them. However, who built these planes is equally intriguing. Almost half of the manpower behind P-47 production were women. Known as “Raiderettes,” these women served in a wide array of positions at Republic. This piece will examine the lived experiences of the Raiderettes at the Republic plant in Evansville, Indiana and how their hard work, sacrifices, and patriotism contributed to the production of over one-third of the Thunderbolts manufactured during World War II.

ON THE ASSEMBLY LINE: WOMEN’S ROLES AT REPUBLIC AVIATION

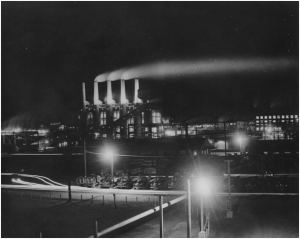

Evansville played a major role in the home front effort throughout the war. In total, fifty different Evansville companies received over $580 million in defense contracts. This included Sunbeam, Serval Inc., Chrysler, and the Missouri Valley Bridge & Iron Co. Shipyard, which produced critical defense industry products such as ammunition, tracer rounds, and landing ship tanks. This booming industry nearly tripled Evansville’s manufacturing workforce and revitalized the previously struggling city. [iii] In 1942, Republic and the U.S. War Department announced they would build a second P-47 factory south of the Evansville Regional Airport. The first facility was located in Farmingdale, New Jersey. Construction commenced at a rapid pace and the plant was finished in August of 1943, three months ahead of schedule. However, P-47 construction was already underway before the factory was even finished, with newly hired workers manufacturing parts in garages, rented factory spaces, and other facilities. Evansville’s first P-47 dubbed “The Hoosier Spirit” flew from the plant on September 19, 1942. The Hoosier Spirit marked the first of over 6,000 Thunderbolts manufactured in Evansville during the span of three years.

From the beginning, Republic sought to hire a substantial number of women workers because men were fighting overseas. Republic recruited women through newspaper advertisements and provided free, educational opportunities. Evansville College (now the University of Evansville) partnered with Purdue University and the U.S. Department of Education to offer twenty-two-night classes in engineering, science, mathematics, aircraft drafting, and other industrial skills. Notably, the Evansville Press wrote that, for the night classes, “Women especially are urged to enroll… The War Manpower Commission estimates that at least two million more women must enter war industries this year.”[iv] Soon after night classes began, Evansville College and Purdue began to offer daytime classes as well to fulfill the needs of night shift workers at Republic and other defense companies. E. C. Surat, district manager of the Purdue war training program, told the Evansville Courier and Press that “Women with mathematical training may be placed at once” in factory positions and urged that women seeking a defense industry job “enroll in the qualifying mathematics course.”[v]

The Evansville Mechanic Arts School also recruited women for their industrial classes. Previously, the school designed courses solely for men, but, upon the outbreak of the war, opened to women “without a halt.” The school especially appealed to homemakers and unemployed women to enroll.[vi] In her article, “Diary of a Riveter,” Raiderette Mary Ellen Ward describes the challenges of these types of training courses and adjusting to the “nerve wracking” noise as they learned drilling techniques, how to measure rivets, and built physical strength to rivet for fourteen plus hours a day.[vii] The City of Evansville and the Republic Aviation Corporation recognized early on the integral role women would play in the home front effort and began recruiting them and providing key training and education for them to succeed in manufacturing roles.

Women from the “tri-state” area of Illinois, Kentucky, and Southern Indiana performed a diverse number of roles, including managerial positions, across the Republic plant. Raiderettes could be found working side by side with men in machining parts, welding metal, wiring electrical components, inspecting aircrafts, and transporting supplies. This makes it impossible to describe a singular, definitive experience among the Raiderettes. However, women across the plant embraced their roles, seeing it as a patriotic duty, and exceeded the expectations of the public. The Muncie Evening Press reported that, in some tasks, women workers across the country exceeded men’s production output by 10 percent or more.[viii] Day-to-day life in the plant consisted of 10 to 14-hour shifts across various departments and, for many, included long commutes of up to 80 miles away a day. Beyond production work, women actively participated in work-adjacent roles, leading the charge on key social services for all Republic employees. Given the amount of time spent at both work and Republic-related events, almost all Raiderettes experienced World War II primarily through the lens of their position at the Evansville plant, making it a key experience to analyze in order to better understand the Indiana home front during World War II.

One Raiderette, Mildred F. Harris, participated in an oral history interview in 2002, providing key insight into the subjective experience of women at Republic. A schoolteacher, Harris entered war work when her husband was drafted in 1943, commuting 55 miles a day, six days a week from her home in Kentucky to work at the Evansville plant. Harris was placed in a supervisory role managing other aircraft inspectors and supervising factory operations. She stated that men respected her and other female inspectors’ position of authority “as long as the inspectors had this army badge on,” and that they recognized the need for women to work in factories as “they couldn’t get enough men to do it.” Despite this, Harris still experienced sexism in the workplace with some of the men calling her nicknames like “Rose,” “Buttercup,” or “Daisy,” despite her position supervising them. Harris largely ignored these nicknames and kept to herself while she performed her job. Like many women, Harris felt a duty to support both her country and male relatives who served in the war, underlining the importance of her position as an aircraft inspector and the pressures of such long days and high stakes. Her experiences also demonstrated that, simply because women now appeared in “male roles,” that sexism and gender roles still pervaded most Raiderettes experiences. [ix]

Women also contributed to the company culture at Republic, actively participating in clubs, the company newspaper, and sports leagues for basketball, softball, bowling, golf, and ping pong. Republic’s clubs competed against other manufacturing companies in Evansville. In addition, women led the charge on hosting social functions like skating nights, formal dances, and even a holiday musical production called “Flying High.” A daycare service was provided for working mothers at the reduced price of 50 cents per week.[x] This proved to be critical as women often found themselves to be “two-job” workers, working at Republic for fourteen hours a day while also continuing to maintain the domestic sphere and raise children, often without the support of their spouse who may have been drafted. Women also formed the “war matrons club,” which catered specifically to older Raiderettes whose sons were serving overseas. This club tracked soldier’s birthdays, wrote to them, and provided a support system for mothers separated from their children due to the war.[xi] While easily overlooked, these services provided necessary social outlets during a period of great change and anxiety in the United States and fostered a strong sense of community for all Republic employees. They also provided workers, many of whom had family members serving overseas, with vital social connections and filled a key gap in societal recreation and relaxation.

While women were praised for their patriotism and largely welcomed into the plant, gender roles still defined the Raiderettes’ wartime experiences. Often, the work of women was more heavily scrutinized than men’s and feminine traits characterized as a detriment to wartime production. This can be seen in Republic Aviation News through warnings against “super-sensitiveness” in the workplace and constant reminders that a woman must uphold or surpass the standards of the men who worked alongside them.[xii] Additionally, extra emphasis was placed on women’s fashion and social life with an entire column called Strictly Feminine. The column reported on social news, like who danced with whom at the canteen, what women were wearing to social functions, and other, non-work related, news. Women were often expected to meet their position’s expectations and perform social and emotional labor while doing so. Republic Aviation News paints a more nuanced picture than that of the one-dimensional and patriotic “Rosie the Riveter,” who flawlessly steps into a traditionally male position just as a man would. Women’s positions and experiences in home front factories were distinct and laced with gender roles and bias as they were expected to do a “man’s job” but in a traditionally feminine manner.

A major point of friction between women and men in the factory was whether women would continue working after the war concluded or if their jobs ought to be relinquished back to male workers. Inspector Harris, upon reflecting on the closure of the plant, stated “Now, what they [the male factory workers] expected them to do, what they wanted them to do when the war was over, [was] to go back home and wash dishes like they had been doing.”[xiii] This attitude is reflected in the fact that, after the government cancelled their wartime contracts with Republic, women disproportionately lost their jobs compared to male workers.[xiv] While it is debated whether women truly desired to return home or sought to continue working in the factories- likely a mix of both- they unilaterally faced unfair obstacles in remaining in the workforce post-war.

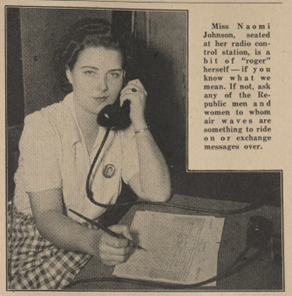

Despite the continued presence of gender bias in the factory, Raiderettes pushed against and broke the glass ceiling in various ways. For example, Naomi Johnson was notable for being the first woman restricted radio operator- a position that allows users to utilize advanced aircraft radios to communicate and direct pilots- in the region. Originally from Marion, Kentucky, Johnson moved to Evansville in 1937 and earned her operator license in 1940 from the Federal Communications Commission. Johnson originally tested police radios in cars but, upon the outbreak of the war, transitioned to Republic Aviation. She began working on electrical equipment but, after nine months, was transferred to a radio control board, where she communicated with pilots flying and landing P-47s at the Evansville Regional Airport. Due to her strong interest in and advanced knowledge of aviation, she was made an honorary member of the Civil Air Patrol. When interviewed by Republic Aviation News, Johnson expressed her strong passion for her work, stating, “The thing I like best about radio work is the fact that it’s something you can never learn enough about. You can just keep studying and studying. But I wouldn’t mind being called a book-worm if I could read about radio.”[xv]

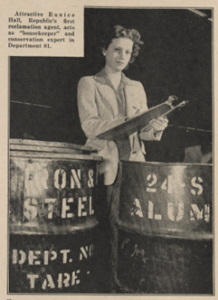

Another woman, Eunice Hall of Newburgh, Indiana, became the first “reclamation agent” at the Evansville plant, a new position that encouraged the conservation of factory materials to reduce waste in the various plant divisions. Working with the Utility Shop division, Hall also served as the division’s Safety Council representative. While Republic Aviation News minimized her position by comparing it to a “housekeeping” role, Hall excelled at leadership by defining this new company role and taking the lead on both shop safety and material conservation, a key aspect of the home front’s defense industry economy.[xvi]

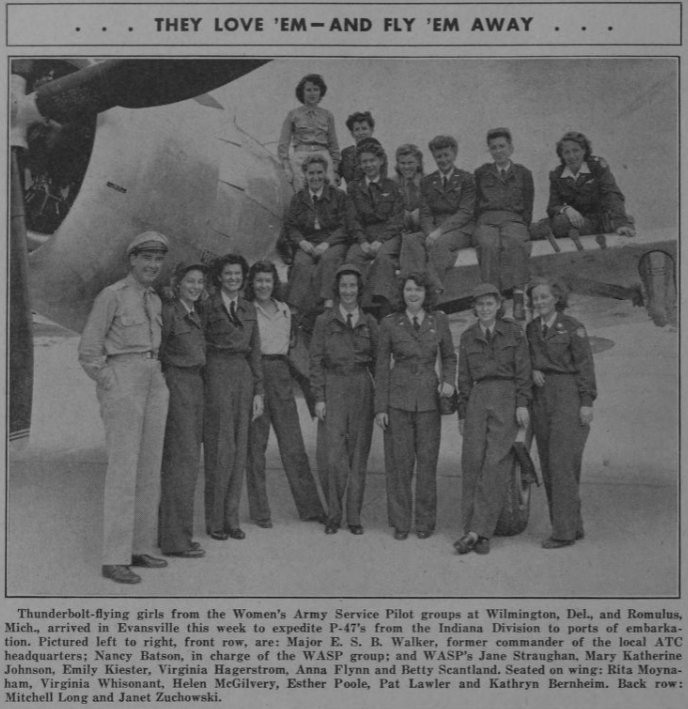

Other women broke into aviation and flew P-47s domestically. The Women Airforce Service Pilots, (WASPs) were elite civilian pilots who supported the war effort by ferrying, testing, and transporting planes. Described as “polished” and having perfect uniforms, the WASPs visited the Evansville plant numerous times to transport Thunderbolts to military bases.[xvii] On October 10, 1943, Theresa James and Betty Gillies landed in Evansville to deliver two Thunderbolts and transport two others. Gillies is notable as the first ever woman to fly a P-47 aircraft.[xviii] In 1944, WASPs regularly began transporting P-47s from the Evansville plant, with Republic Aviation News stating that 85 women would participate and, each month, 16 of them would fly to the Evansville plant to ferry completed planes to military bases.[xix] While the activities of the WASPs generated much interest both in the news and amongst factory workers, it is reported that the WASPs largely stayed separated from the rest of the factory and focused on their positions.[xx]

As evidenced by the previous examples, women held diverse roles within Republic Aviation and navigated their new, public-facing roles in a variety of ways. Some women, like those in the War Matrons club or Eunice Hall, embraced social responsibilities at the plant by serving on committees and clubs and embracing a more “traditionally feminine” role at Republic. Meanwhile, others, such as the WASPs or Harris, were more reserved in their roles and attempted to ignore or minimize gender roles and bias. However, the common thread of all of these women is that they collaborated with both male workers and one another, pushing against traditional gender roles to best serve the United States during World War II. Their sacrifices were largely recognized and praised by the public. However, it was also expected that they would revert to traditional roles upon the end of the war which, generally, is what occurred. Despite this, these women successfully navigated a challenging period in American history to provide a vital service on the home front and ought to be remembered for their work.

On August 21, 1945, Republic Aviation announced they would be ending all production at Evansville and the plant was soon listed for sale. Upon its closure, the plant had produced over one-third of all the P-47 Thunderbolts in the world, hired thousands of employees, and infused millions of dollars into the local economy. In addition, the plant had gained national recognition, earning three Army-Navy E awards for “excellence in production.”[xxi] This prestigious award was granted to 5% of all eligible plants and represented the top echelon of home front production.[xxii] The plant’s production was considered so outstanding, that President Franklin D. Roosevelt even visited the plant on April 27, 1943 as part of a 17-day, 20-state tour of America’s defense industry, presenting awards to multiple employees.[xxiii]

Without the thousands of women who worked at the Republic plant, these national honors would not have been achieved. Similarly, the quality and reliability of the P-47, which is world-renowned and contributed to Allied Forces’ air superiority during WWII, would not have been possible without the dedicated hands that constructed the planes at an unprecedented pace. While the lives and roles of the Raiderettes at the Republic factory did not ascribe to the simplified “Rosie the Riveter” archetype, they were critical to the defense effort nonetheless, and ought to be commemorated as both Indiana and national heroes.

Notes:

[i] “Republic P-47 Thunderbolt,” National Museum of World War II Aviation, accessed https://www.worldwariiaviation.org/aircraft/republic-p47-thunderbolt; National Air and Space Museum, “Republic P-47D-30-RA Thunderbolt,” Smithsonian Institution, n.d., accessed https://www.si.edu/object/republic-p-47d-30-ra-thunderbolt%3Anasm_A19600306000.

[ii] Dario Leone, “The Story of the P-47 that Safely RTB after it Had a Wing Sheared off Against a Chimney during a Strafing Run and its Tail Damaged by Spitfires that Mistook it for a German Fighter,” The Aviation Geek Club, September 20, 2023, accessed https://theaviationgeekclub.com/the-story-of-the-brazilian-p-47-that-safely-rtb-after-it-had-a-wing-sheared-off-against-a-chimney-on-a-strafing-run-and-its-tail-damaged-by-spitfires-that-mistook-it-for-a-german-fighter/.

[iii] James Lachlan MacLeod, Evansville in World War II (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015); David E. Bigham, “The Evansville Economy,” Traces of Indiana And Midwestern History 3, no. 4 (Fall 1991): 26-29, accessed https://images.indianahistory.org/digital/collection/p16797coll39/id/7111/rec/3; Hugh M. Ayer, “Hoosier Labor in the Second World War,” Indiana Magazine of History 59, no. 2 (June 1963): 95-120, accessed https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/8960/11634.

[iv] “College to give Classes in War Work,” Evansville Press, September 12, 1943, accessed Newspapers.com.

[v] “Day War Training Classes Planned,” Evansville Courier, October 15, 1943, accessed Newspapers.com.

[vi] “These Doors Never Close: Mechanic Arts School Has Prominent Part in War Work Training Program,” Evansville Courier and Press, July 2, 1942, accessed Newspapers.com.

[vii] Mary Ellen Ward, “Diary of a Riveter,” Republic Aviation News, February 12, 1943, accessed Indiana State Library.

[viii] “Two-Job War Worker: She Does a Man-Sized Job on Production Line Plus ‘Women’s Work’ of Maintaining a Home,” Muncie Evening Press, November 5, 1942, accessed Newspapers.com.

[ix] James Russell Harris, “Rolling Bandages and Building Thunderbolts: A Woman’s Memories of the Kentucky Home Front, 1941-1945,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, (Spring 2002): 167-194, accessed JSTOR.

[x] “New Plan for Child Care Offered: Play Center Fills Need Before and After School,” Republic Aviation News, November 26, 1943, accessed Indiana State Library.

[xi] “War Mothers Organized at Republic Plant,” Evansville Press, April 29, 1943, accessed Newspapers.com.

[xii] “A Message from Ellen J. Dilger,” Republic Aviation News 100, no. 2, January 29, 1943, accessed Indiana State Library.

[xiii] Harris, “Rolling Bandages,” 182.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] “First Woman Restricted Radio Operator in This Region is Republic’s Naomi Johnson,” Republic Aviation News, September 3, 1943, accessed Indiana State Library.

[xvi] “Utility Shop Girl Becomes First Official Reclamation Agent at Indiana Division,” Republic Aviation News, January 7, 1944, accessed Indiana State Library.

[xvii] Harris, “Rolling Bandages,” 184-185.

[xviii] “First Woman Ever to Fly a Thunderbolt is One of Two Girls Landing Here in P-47s,” Republic Aviation News, October 15, 1943, accessed Indiana State Library.

[xix] “First Squadron of Girl Pilots Here to Fly P-47’s,” Republic Aviation News, August 1, 1944, accessed Indiana State Library.

[xx] Harris, “Rolling Bandages,” 184-185.

[xxi] “Raiders Win Army-Navy ‘E’ I.D. [Indiana Division] Gains Highest Production Honor,” Republic Aviation News, May 5, 1944, p. 1, accessed Indiana State Library; “Your Army-Navy ‘E,’” Republic Aviation News, May 5, 1944, p. 2, accessed Indiana State Library; “Army, Navy Honor Raiders,” Republic Aviation News, May 26, 1944, p. 1, accessed Indiana State Library; “Raiders Win 2nd ‘E’ Award: Achievement lauded by Marchev,” Republic Aviation News, November 3, 1944, p. 1, accessed Indiana State Library; “I.D. Earns 2nd Army-Navy ‘E’ for Outstanding Work,” Republic Aviation News, November 3, 1944, p. 2, accessed Indiana State Library; “Raiders Win 3rd Army-Navy “E,” Republic Aviation News, May 25, 1945, p. 1, accessed Indiana State Library.

[xxii] “Army-Navy E Award,” Naval History and Heritage Command, September 15, 2020, accessed https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/a/army-navy-e-award.html.

[xxiii] “Camera Highlights of the President’s Visit to the Indiana Division on Tuesday, April 27,” Republic Aviation News, May 21, 1943, p. 4-5, accessed Indiana State Library; “Roosevelt visits Evansville; Sees P-47 Dive at 500 M.P.H,” Indianapolis News, April 29, 1943, p. 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Evansville Aircraft Plant Receives Visit of President,” Muncie Evening Press, April 29, 1943, p. 9, accessed Newspapers.com.