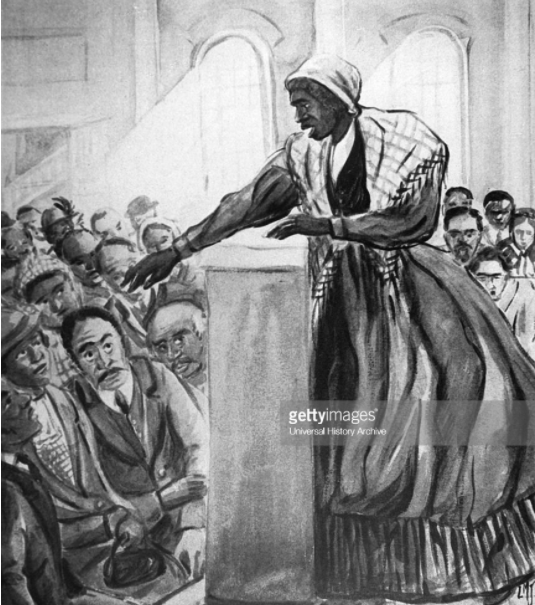

“Five prominent suffragists wooed Nora, stormed Carmel, showed Westfield the sun of political equality rising in the East, and splintered their verbal swords, maces, spears and daggers against two club closing days and a bridge party in Noblesville.” The June 6, 1912, edition of the Indianapolis Star vividly described what was probably the first women’s suffrage automobile tour in the state. The suffragists in question—Sara Lauter, Grace Julian Clarke, Mrs. R. Harry Miller, Julia Henderson, and Mrs. W.T. Barnes—represented the Woman’s Franchise League (WFL), one of the two major suffrage organizations in the state (the other was the Equal Suffrage Association).

This Hamilton County event was part of the Woman’s Franchise League’s re-energized campaign to get the vote. After sixty-one years of petitioning state legislators to enact laws that recognized women’s right to vote with no success, the WFL decided to take its arguments more directly to the people. Suffragists wanted to better inform the public about the benefits for all people when women voted and hoped that constituents would in turn pressure their legislators to enact women’s suffrage legislation. The WFL needed to garner enough support over the summer of 1912, when travel was easiest in the still very rural state, to have suffrage legislation introduced in the 1913 state legislative session. Gov. Thomas Marshall had added an urgency to the task with his proposed new state constitution. Marshall wanted only “literate male citizens of the United States who were registered in the state and had paid a poll tax for two years” to be permitted to vote. The existing state constitution, with its arcane amendment system, which had prevented women from gaining the vote in 1883, at least did not designate a sex as criteria for voting as Marshall’s proposal did.

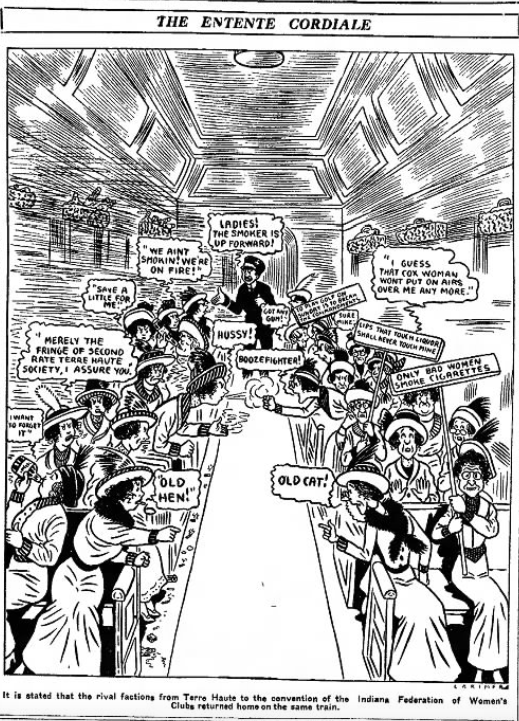

To get their message to the people, the WFL came up with innovative publicity ideas. At the WFL’s request, women’s suffrage supporter and former U.S. Vice-President Charles W. Fairbanks hosted a heavily attended suffrage-themed lawn party at his Meridian Street home. WFL member Lucy Riesenberg suggested a suffrage baseball game. The Indianapolis Athletic Association, owners of the local field, agreed to host the event as long as the WFL sold 3,000 tickets at 50 cents each. The suffragists deemed those terms “unreasonable” and dropped the idea. Grace Julian Clarke, ardent member of both the WFL and the Federation of Clubs, urged the group to pursue a suffrage auto tour as she heard had been completed by suffragists in Wisconsin. Sara Lauter offered the use of her car for the occasion and they almost immediately put the plan into action. What better way to reach women than to go directly to them.

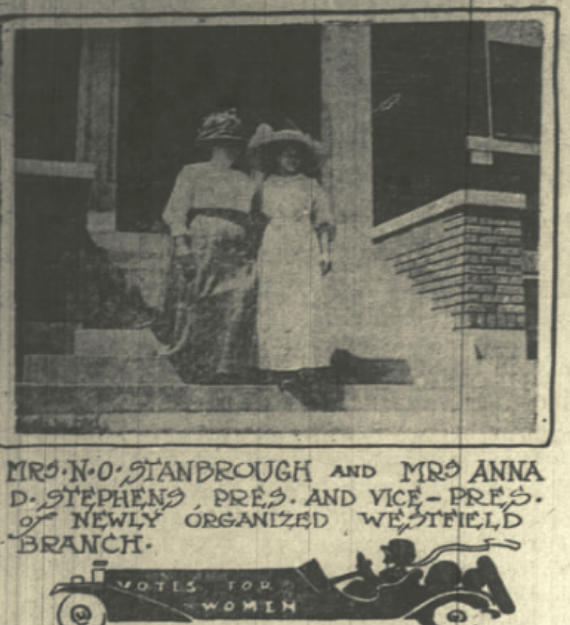

On June 5, the five suffragists fastened a yellow “Votes for Women” banner to the side of Lauter’s car, loaded suffrage flyers and themselves into it, and set out from Indianapolis at 9:30 a.m. Traveling north, they left some of the flyers behind in Nora and then motored to Westfield. A group of men and women suffragists hosted the travelers at the public library, where everyone enjoyed lunch and the Indianapolis women gave short talks about how women voters could improve the lives of mothers, working women, and everyone else. Westfield suffragists formed a new WFL branch league on the spot, with Mrs. N.O. Stanbrough named President of the new group, Anna D. Stephens named Vice President, and Lizzie Tresmire as both Secretary and Treasurer. The enthusiastic Westfield women even offered to travel to the village of Carmel, just three or four miles to the south, to establish a branch suffrage league there. When the Indianapolis suffragists returned to their car to take their message to Noblesville, they found it decorated with peonies, roses, and lilacs.

The Noblesville visit did not go as planned. The WFL suffragists had unfortunately chosen an inconvenient day for their visit. Women’s clubs did not meet in the summer and June 5 was the last meeting day of the year for two Noblesville clubs. The final day of the club season was a highlight of any club’s yearly program and not to be missed—even for a suffrage auto tour. Disappointed with the small number of women who attended the meeting at the First Presbyterian Church, but understanding the importance of the last day of the club year, WFL suffragists made the best of a bad situation. First, they promised to return the following week, and Mrs. Harry Alexander, Mrs. Walter Sanders, and Mrs. Charles Neal of Noblesville agreed to make the arrangements. Second, Clarke and Lauter took to the streets, where they distributed suffrage flyers and talked to unsuspecting shoppers and business owners around the courthouse square. At the end of the day, the suffragists headed south to Allisonville, distributed more flyers, returned to Indianapolis around 5:00, and declared their first auto tour “a good day’s work.”

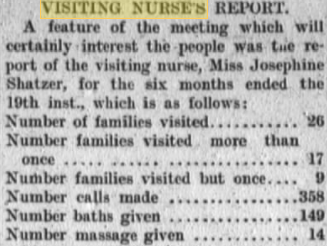

Motivated by their warm reception in Westfield and undaunted by the problems in Noblesville, suffragists chose Boone County as their next destination and traveled to Zionsville and Lebanon the following week. Hanging the “Votes for Women” banner from Mary Winter’s car, Winter, Julia Henderson, and Celeste Barnhill took on the task. The Rev. G.W. Nutter hosted the suffrage meeting at his church, the Zionsville Christian Church. He announced his full support for women voting and asked to be allowed to join the WFL. As had happened in Westfield, other men also attended the meeting and displayed as much support for the cause as women. Winter and Barnhill welcomed them and noted the support the WFL received from many men. They worried more, it seems, that some women remained indifferent to the vote. They tried to turn that indifference into support by explaining how the vote had the potential to improve the lives of all women through enactment of health and sanitation laws, regulations on child labor, and even by limiting or prohibiting the manufacture or sale of alcohol.

Leaving behind suffrage flyers in Zionsville, the women trekked to the courthouse in Lebanon for their next meeting. This time, Mary Winter stressed that women voters could bring about the introduction of new legislation that dealt with working conditions and wages, liquor legislation, and vice regulation. She noted that women who worked in factories realized the need for the ballot more than women who did not work outside the home. She hoped that those two groups of women would join forces and improve working and living conditions for everyone. As with Zionsville, while the crowd expressed an interest in the cause, Boone County residents did not create a new suffrage organization.

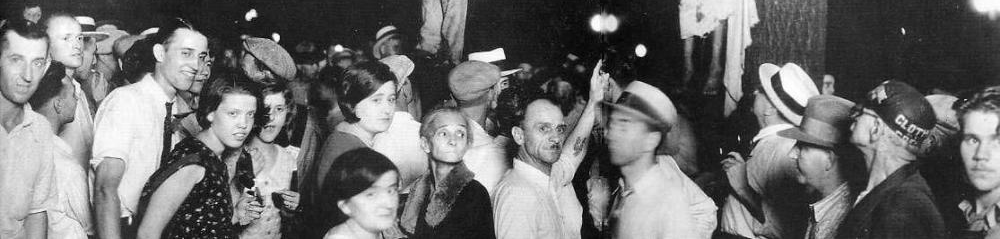

In the end, Marshall did not get his new state constitution that would have explicitly forbidden women from voting. He instead joined the ticket of Democratic presidential candidate Woodrow Wilson and in the November 1912 election became the Vice President of the United States. No suffrage legislation passed out of the 1913 state legislative session. In spite of that setback, auto tours became a standard means to reach women. In Indianapolis, suffragists used automobiles as speaking platforms for impromptu street meetings. By standing in their cars, women were elevated enough above the crowd to clearly be seen and heard.

As a sign of the success of the auto tours, street meetings, and other suffrage work, in 1917 the state legislature had granted women partial suffrage (they could vote for some state officials). After a court challenge, however, the state Supreme Court ruled the partial suffrage bill unconstitutional. Before that ruling, suffragists, sometimes with a public notary in tow, traveled the state in cars adorned with “Votes for Women” banners to be sure that women registered to vote. Thousands of women registered in the summer of 1917 in part because of the persistent auto tours of the WFL. The experiment of 1912 became the standard means of reaching Hoosier women and promoting suffrage in even the remotest part of the state.

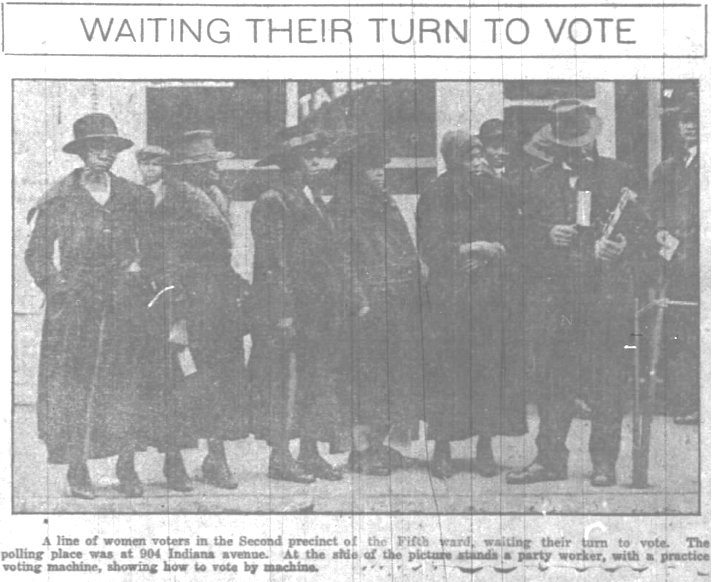

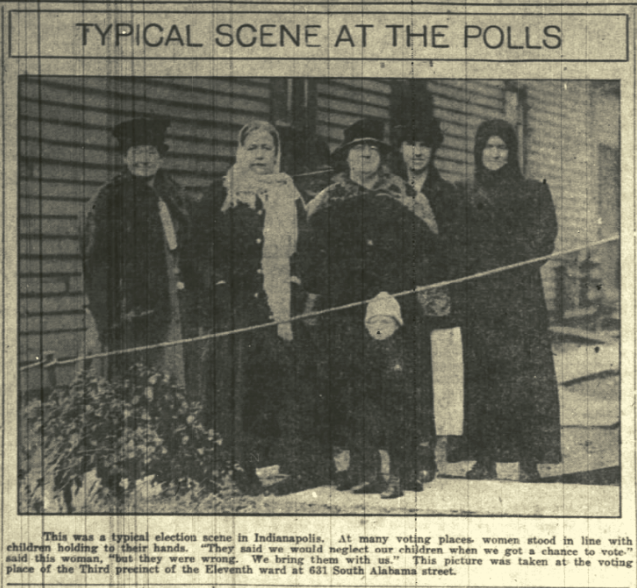

On January 16, 1920, the Indiana General Assembly ratified the 19th Amendment to the federal Constitution which recognized women’s right to vote. Finally, after federal ratification, Indiana women from all walks of life, sometimes with children in tow, stood in line in the bitterly cold weather to vote on November 2, 1920. Even an automobile accident did not prevent one Indianapolis woman from voting when, after a quick trip to the hospital, a friend drove her to her polling place. The automobile proved crucial not only in getting the vote, but to the voting booth.

Further Reading:

Susan Goodier and Karen Pastorello, Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State (Ithaca: Three Hills Press of Cornell University Press, 2017).

Genevieve G. McBride, On Wisconsin Women: Working for Their Rights from Settlement to Suffrage (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1993).

Eleanor Flexnor and Ellen Fitzpatrick, Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Enlarged Edition 1996).