Spanish Influenza hit Indiana in September of 1918. While the virus killed otherwise healthy soldiers and civilians affected by WWI in other parts of the world since the spring, most Hoosiers assumed they were safe that fall. Still, newspaper headlines made people nervous and health officials suspected that the mysterious flu was on their doorstep.

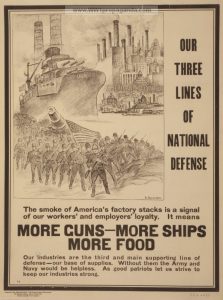

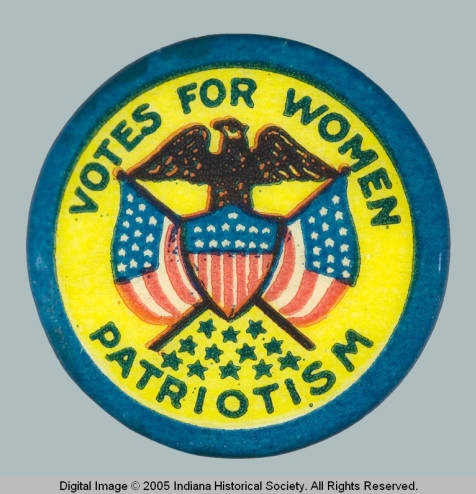

In April of 1917, the United States joined the Allied effort. Residents of Indianapolis, like most Hoosiers, largely united around the war effort and organized in its support. In addition to registering for military service, the National Guard, and the Red Cross, they organized Liberty Loan drives to raise funds and knitting circles to make clothing for their soldiers. Farmers, grain dealers, and bankers met to assure adequate production and conservation of food. They improved the roads in order to mobilize goods for the war effort, including a road from Indianapolis to nearby Fort Benjamin Harrison located just nine miles northeast of downtown Indianapolis. This penchant for organization would be extremely valuable throughout the bleak coming months.

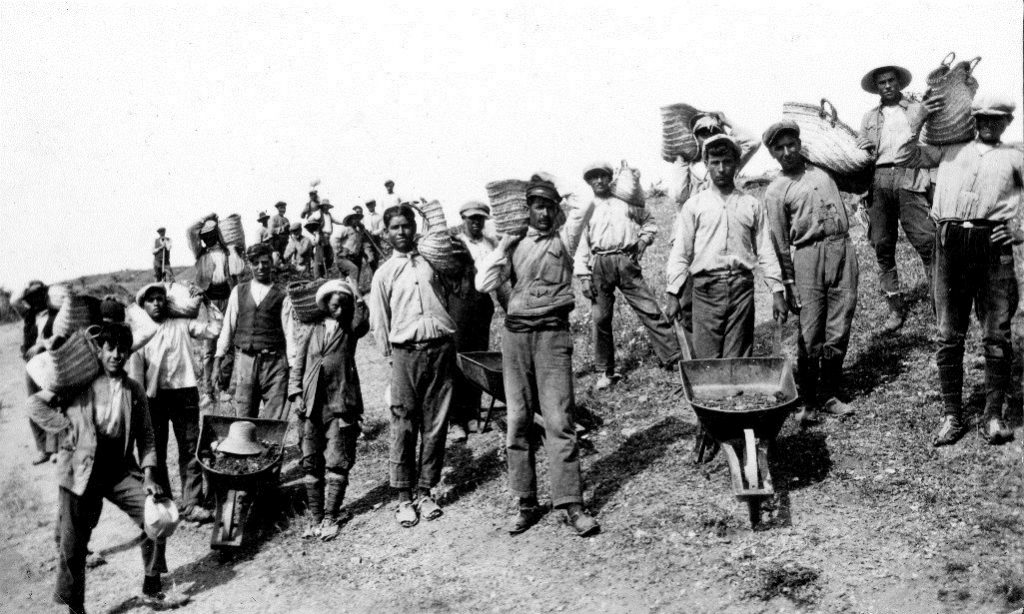

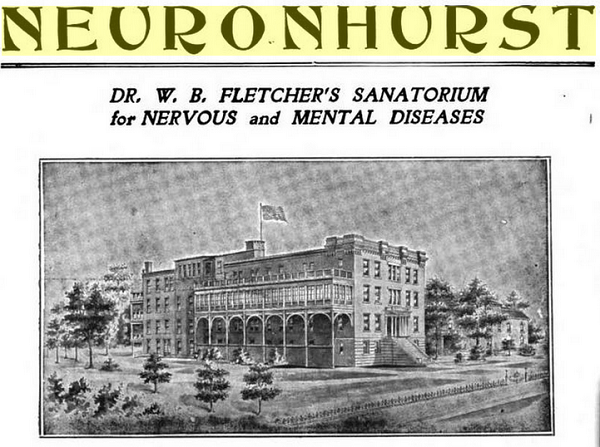

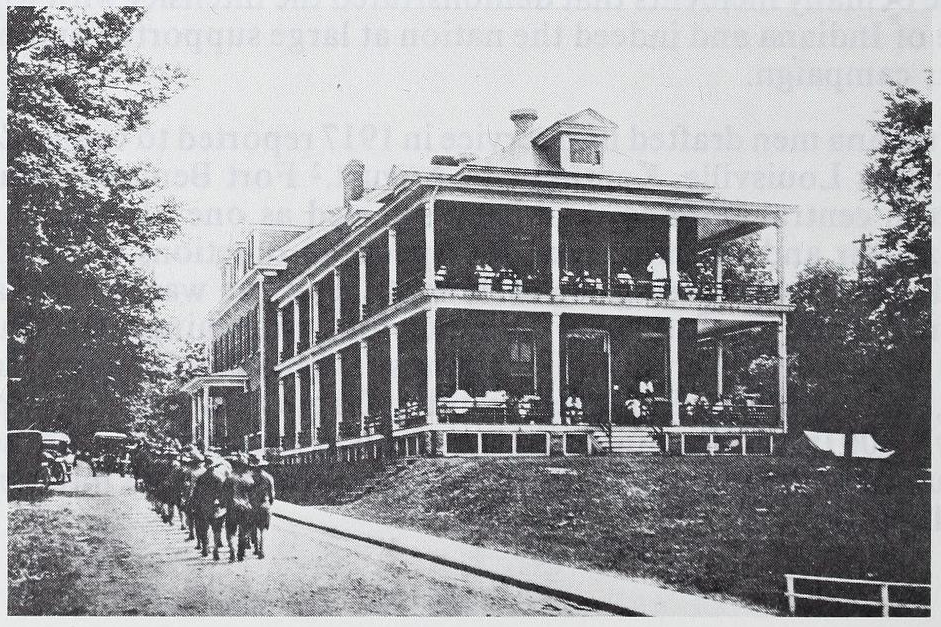

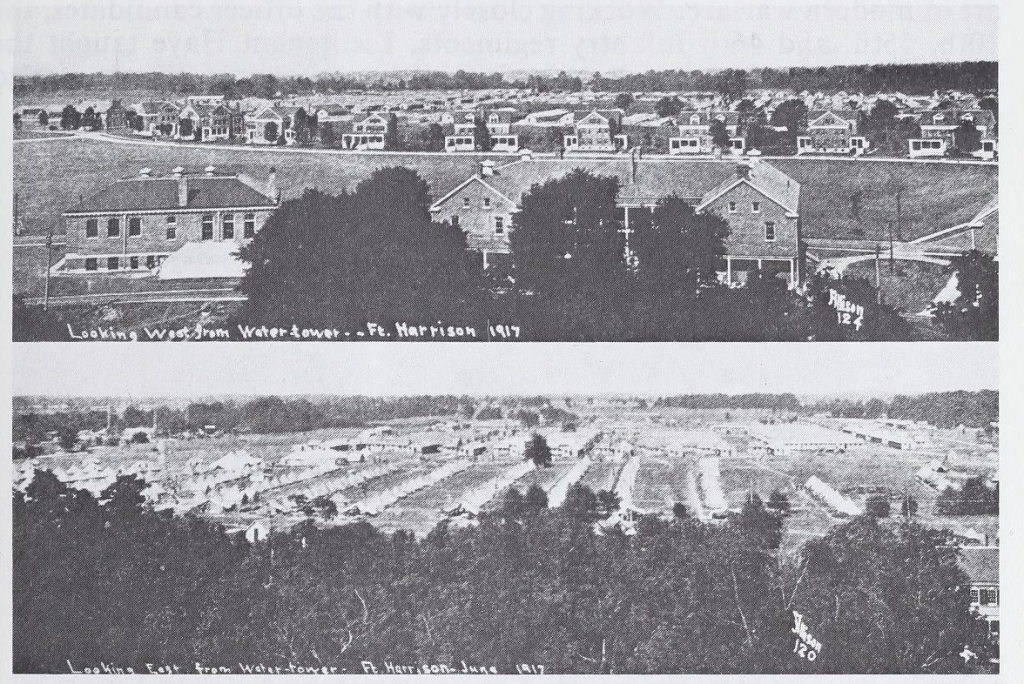

The U.S. Army constructed Fort Benjamin Harrison over a decade earlier with the intention of stationing one infantry regiment there. However, with America’s entry into the war, Fort Ben (as it was colloquially known) became an important training site for soldiers and officers. It also served as a mobilization center for both Army and National Guard units. In August 1918, just prior to the flu outbreak, the War Department announced that the majority of the fort would be converted into General Hospital 25. The Army planned for the hospital to receive soldiers native to Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois who would be returning from the front as wounded, disabled, or suffering from “shell shock.” By September, the newly established hospital was ready to receive a few hundred “wounded soldiers returning from France.” But the soldiers stationed there preparing to receive causalities, began to fall ill themselves.

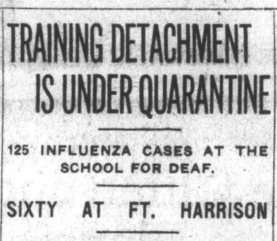

On September 26, 1918, the front page of the Indianapolis News announced unidentified cases of illness in training detachments stationed at the Indiana School for the Deaf, the Hotel Metropole, and Fort Benjamin Harrison. The detachment at the deaf school denied that men were infected with the deadly Spanish Influenza that was on the rise as soldiers returned to the U.S. from the front. The medical officers instead claimed “the ailment here is not as serious as that prevailing in the east.”

Despite this reassurance, the high number of cases was alarming. The major in command of the detachment issued a quarantine. The lieutenant from the hotel detachment also claimed that none of the illnesses there were caused by Spanish influenza. He referred to the cases as “stage fright,” as opposed to a full outbreak of the disease. At Fort Benjamin Harrison, sixty men suffered from influenza, but the Indianapolis News reported “none has been diagnosed as Spanish influenza and no case is regarded as serious.” The medical officers there reported, “An epidemic is not feared.”

While the front page reassured the city’s residents that there was nothing to fear and that the military had everything under control, a small article tucked away on page twenty-two hinted at the magnitude of the coming pandemic. Twenty-seven-year-old Walter Hensley of Indianapolis had died of Spanish Influenza at a naval training detachment on the Great Lakes. His body arrived in the city for burial soon after, a funeral that would be the first of many for otherwise healthy young military men. Only a few weeks later, Indianapolis would be infected with over 6,000 cases with Fort Benjamin Harrison caring for over 3,000 patients in a 300 bed facility before the end of the epidemic.

Indianapolis was not alone in its unpreparedness, as little was known about the strange flu. Influenza was certainly not uncommon, but most flu viruses killed the very young, sick, and elderly. The 1918 influenza, on the other hand, killed otherwise healthy young adults ages twenty to forty – precisely the ages of those crowded into military camps around the world. Furthermore, the disease could spread before symptoms appeared. Infected soldiers and other military personnel with no symptoms amassed in barracks and tents, on trains and ships, and in hospitals and trenches. As troops moved across the globe, so did the flu. It took on the name “Spanish influenza,” because unlike France and England, Spain did not censor reports of the outbreak.

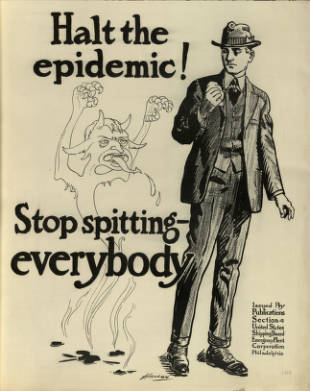

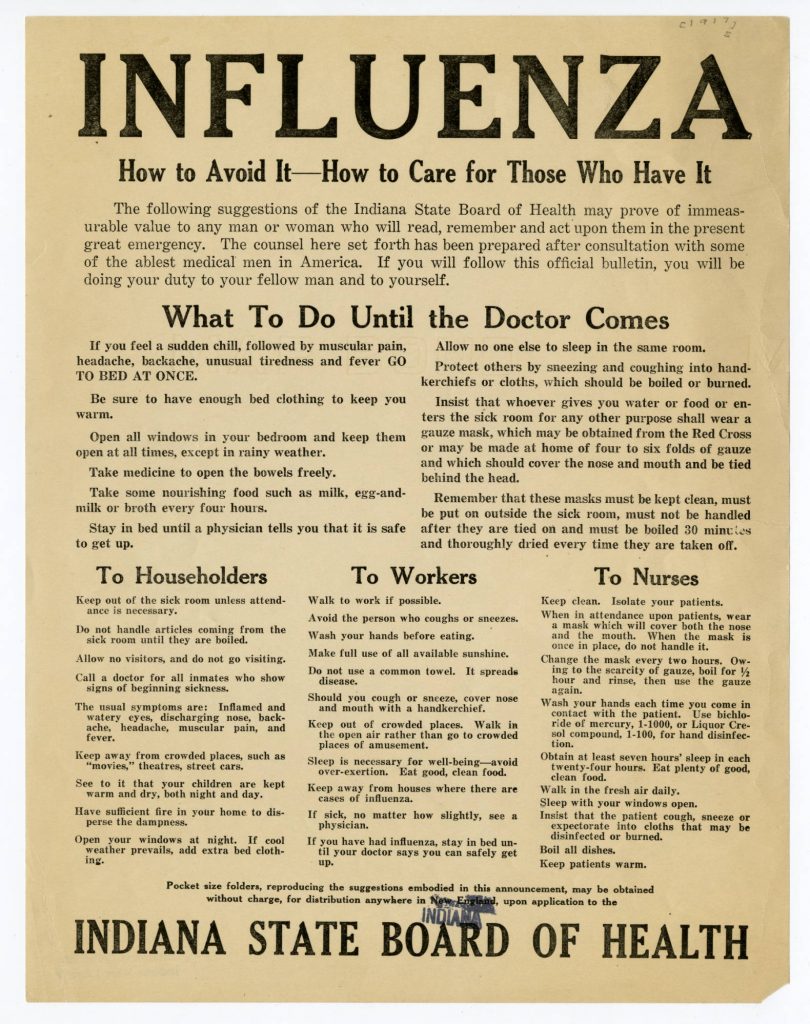

While many modern historians and epidemiologists now believe the pandemic likely began in a crowded army camp in Fort Riley Kansas, Americans in 1918 feared its spread from Europe and took some unlikely precautions. On July 3, 1918, the South Bend News-Times assured its readers that a Spanish passenger liner that had arrived in an Atlantic port “was thoroughly fumigated and those on board subjected to thorough examination by federal and state health officers.” Such measures did little to stop the flu, however, and by September 14 the South Bend newspaper reported on several East Coast deaths from Spanish influenza. On the same day, the Indianapolis News printed a notice from the Surgeon-General Rupert Blue, head of the U.S. Public Health Service, offering advice for preventing infection. These public notices became routine over the following months of the pandemic. Among methods listed for preventing the spread of the disease, Blue recommended “rest in bed, fresh air, abundant food, with Dover’s powders for the relief of pain.” He also warned of the “danger of promiscuous coughing and spitting.”

On September 19, 1918, Surgeon-General Blue sent a telegraph to the head health officer of each state requesting they immediately conduct a survey to determine the prevalence of influenza. In response, Dr. John Hurty, Indiana’s Secretary of the Board of Health, telephoned the local health officials in each city requesting a report. Hurty warned that the flu was “highly contagious,” but stated that “quarantine is impractical,” according to the Indianapolis News. Instead, he offered Hoosiers this advice:

Avoid crowds . . . until the danger of this thing is past. The germs lurk in crowded street cars, motion picture houses and everywhere there is a crowd. They float on dust, and therefore avoid dust. The best thing to do is to keep your body in a splendid condition and let it do its own fighting after you exercise the proper caution of exposure.

One week later, hundreds of men were sick with influenza in Indiana training camps. Again Hurty offered the best advice that he could while advising citizens to remain calm. However, he had to admit: “It has invaded several of our training camps and will doubtless become an epidemic in civil life.” He advised:

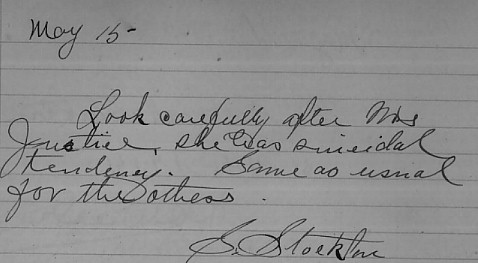

If all spitting would immediately cease, and if all coughers and sneezers would hold a cloth or paper handkerchief over their noses and mouths when coughing or sneezing, then influenza and coughs and colds would almost disappear. We also must not forget to tone up our physical health, for even a few and weak microbes may find lodgment in low toned bodies. To gain high physical tone, get plenty of sleep in a well ventilated bedroom. Don’t worry, don’t feast, don’t hurry, don’t fret. Look carefully after elimination. Eat only plain foods. Avoid riotous eating of flesh. Go slow on coffee and tea. Avoid alcohol in every form. Cut out all drugs and dopes . . . Frown on public spitters and those who cough and sneeze in public without taking all precautions.

Most notably, in this same September 26 front page article in the Indianapolis News, Hurty stated that Indiana had “only mild cases . . . and not deaths.” This would soon change.

Despite these public reassurances, Hurty and other Indianapolis civic leaders knew they needed to do more to prepare. Since little was known about how the flu spread, these men tried to keep the city safe using their intuition. A clean city seemed like a safer city, so they organized a massive clean up. On September 27, the Indianapolis News reported:

To prevent a Spanish Influenza epidemic in Indianapolis, Mayor Charles W. Jewett today directed Dr. Herman G. Morgan, secretary of the city board of health, to order all public places – hotel lobbies, theaters, railway stations and street cars – placed at once in thorough sanitary condition by fumigation and cleansing.

The article noted that in other cities local officials had been unable to prevent widespread infection and that Indianapolis should learn from their failures and “get busy now with every preventative measures that can be put in operation to make conditions sanitary so that infection will not spread.”

By the end of the month, influenza had reached the civilian population. Officials continued to discourage people from gathering in crowds and encouraged anyone with a cough or cold to stay home. The News reported that Indianapolis movie houses had begun showing films on screens in front of the buildings instead of inside the theaters.

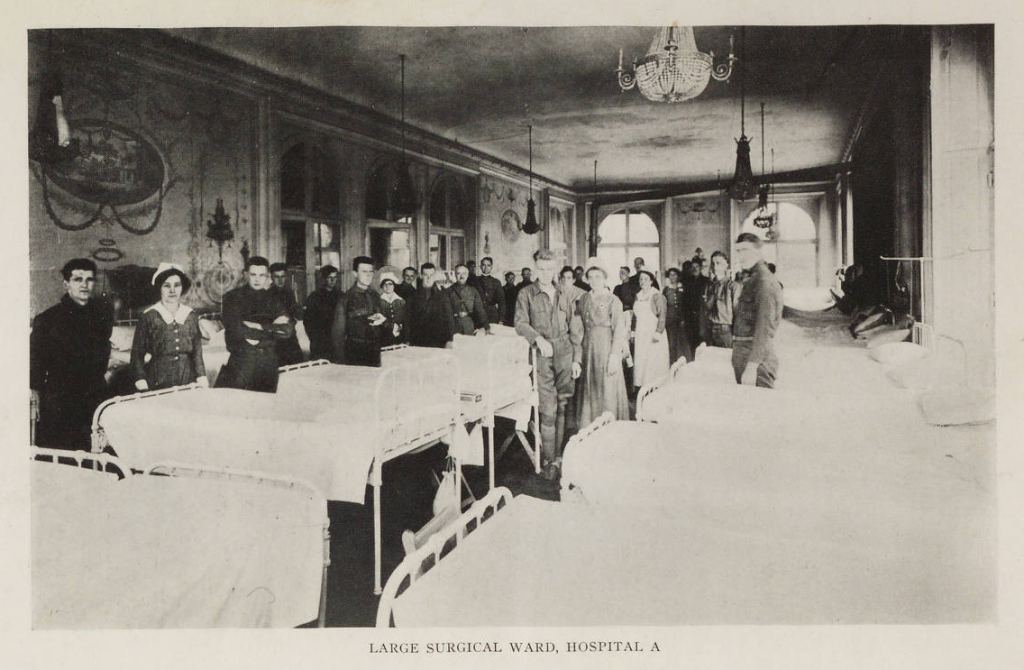

Meanwhile, the numbers of infected men at Fort Benjamin Harrison rose. By the end of September, officers in charge of the base hospital reported that there were “about 500 cases of respiratory disease” at the camp. Although newspapers still reported that it was unclear whether these illness were indeed Spanish influenza, it was clear that the situation was growing dire. Because so many nurses believed Indiana was safe from the pandemic and volunteered to work out east to fight the virus, the fort’s hospital only had twenty trained nurses to care for the hundreds of sick men. The Indianapolis News reported that enlisted soldiers were “being employed as nurses” and that one battalion of engineers had been completely quarantined. Notices of soldiers dying from influenza and related pneumonia began to fill the pages of Indianapolis newspapers.

On Sunday night, October 6, 1918, ten soldiers died in the fort’s hospital bringing the total for the week to forty-one deceased soldiers. Four civilians died from influenza and six more from the ensuing pneumonia. At the fort, officials reported 172 new cases of influenza (bringing the total to 1,653 sick soldiers). Of these, the base hospital was attempting to care for 1,300 men.

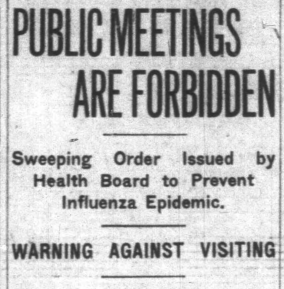

In response, Dr. Morgan announced “a sweeping order prohibiting gatherings of five or more persons.” The front page of the News read, “PUBLIC MEETINGS ARE FORBIDDEN,” and noted that all churches, schools, and theaters were closed until further notice. Only gatherings related to the war effort were exempt, such as work at manufacturing plants and Liberty loan committee meetings. The prominent doctor even discouraged people from gathering at the growing numbers of funerals, encouraging only close family to attend. In October of 1918, Indianapolis must have looked like a ghost town.

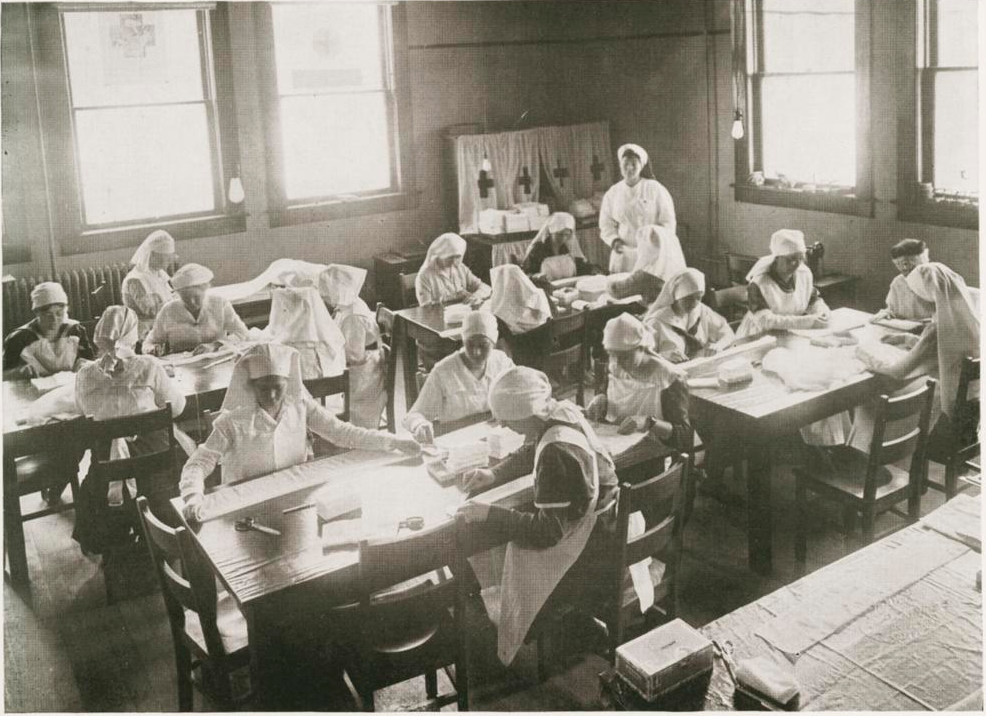

The sick desperately needed nurses and nowhere more than at Fort Benjamin Harrison. Two front page Indianapolis News headlines for October 7 read, “Ft. Harrison Soldiers in Dire Need of Nurses,” and “Graduate Nurses Are Needed for Soldiers.” The News reported that at Fort Ben “soldier boys are dying for lack of trained help” and that the “few nurses in service are worn to the point of exhaustion.” Officers of the local Red Cross worked to redirect nurses who were awaiting transport overseas to the local effort against influenza, while the women of the motor corps of the Indianapolis Red Cross were busy transporting needed supplies by automobiles.

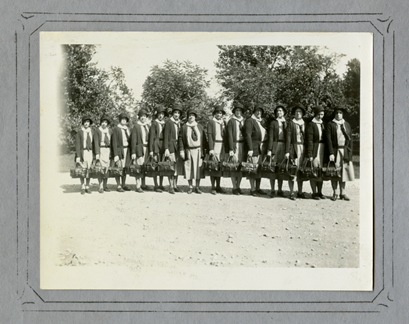

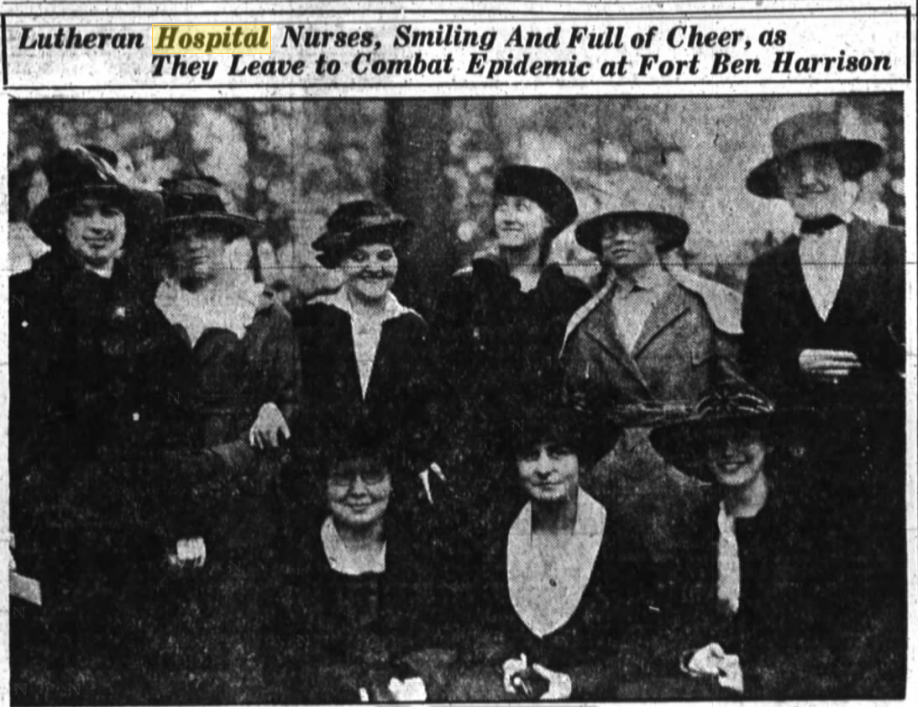

The rest of the newspaper that day was filled with reports on school closings, cancelled meetings, the numbers of sick in various counties, and funerals. The plague was peaking and Fort Benjamin Harrison suffered the most. While most residents of Indiana stayed far away from the infected camp, the brave women of Lutheran Hospital in Fort Wayne took their nursing skills into the heart of the epidemic. The Fort Wayne Sentinel reported on October 7, the same day the Red Cross called urgently for nurses, “10 Local Nurses Respond.” The paper continued:

Willing to risk their lives in the nation’s service in helping combat the ravages of Spanish influenza, ten Lutheran hospital nurses left the city . . . for Fort Benjamin Harrison, near Indianapolis, Ind., where they will enter service in the military base hospital, which is very urgently in need of qualified nurses to aid in fighting the epidemic.

The following day, the Sentinel published a picture of the brave nurses and the local paper praised their “patriotic devotion to place their training at the disposal of their government even at the risk of their lives.”

The same day, a medical officer from the fort hospital told the Indianapolis Star that several trained nurses had reported for duty “within the last few hours to relieve the situation” and that “everything that can be done for the boys is being done.” The Star reported that the officer was responding to “wild rumors” that the soldiers were not getting adequate care. However, the Indiana Red Cross and Board of Health knew that more nurses were needed. On October 11, the Fort Wayne Sentinel shared Dr. Hurty’s report that “during last night thirty soldiers had succumbed to the ravages of the epidemic at Fort Harrison, some of them expiring before their uniforms could be removed from them.” One of the men was Captain C. C. Turner of the medical reserve who had been sent to the fort from another camp only a few days before to help combat the influenza outbreak. His records had not even arrived yet and his relatives could not be contacted.

The situation at the fort prompted Dr. Morgan and several other leading doctors of the city to issue a statement. The doctors praised the efforts of the hospital staff and volunteers. They stated:

The medical staff of Camp Benjamin Harrison has succeeded in fourteen days in expanding a hospital of about 250 beds to one of 1,700 beds by occupying the well-built brick structures formerly used as barracks. These they were able to equip adequately with the assistance of the American Red Cross which . . . proved itself able to supply every demand made by the army on the same day the request was made.

The doctors reported that the hospital had treated 2,500 patients in the previous two weeks. Despite their heroic efforts, the epidemic persisted.

The city also bolstered its efforts as the number of infected rose to 1,536 civilians. On October 11, the Indianapolis News reported 441 new cases of influenza in a twenty-four hour period. In response, Dr. Morgan announced that the city board of health “enlarged the order against public gatherings of every description” and that the Indianapolis police department would enforce the order. “Dry beer saloons,” which were prohibition era gathering places, were closed. Department stores were prohibited from having sales and would be closed completely if found too crowded. Finally, the board of health directed its officers to post cards reading “Quarantine, Influenza,” on houses containing a sick person. The next twenty-four hours brought the city 250 new cases and the fort 47 new cases of Spanish flu. In that same period, twenty four young men died at Fort Benjamin Harrison. The epidemic was peaking.

A week later there was some evidence that the virus began to relax its grip on the fort, if not the city. The Indianapolis News reported that while the previous twenty-four hours had brought twenty-eight deaths to the city, the fort suffered only four. And while the city reported 252 new civilian cases, the fort reported only twelve new cases. Since the fort was struck by influenza before the city, civilians must have seen this decrease at the fort as a good sign. The plague had almost run its course.

On October 30, Dr. Hurty announced that the closing ban would be lifted in Indianapolis. Newspapers reported the lowest number of new cases since the start of the deadly month and Fort Harrison reported that not one person had died in the previous twenty-four hours. Schools could reopen Monday, November 4 and people with no cold symptoms could ride street cars and attend movie theaters. Through the end of 1918 and the beginning of 1919, there were small resurgences of the epidemic. Morgan ordered the wearing of gauze masks in public and discouraged gatherings. However, the worst had passed, and the war had ended.

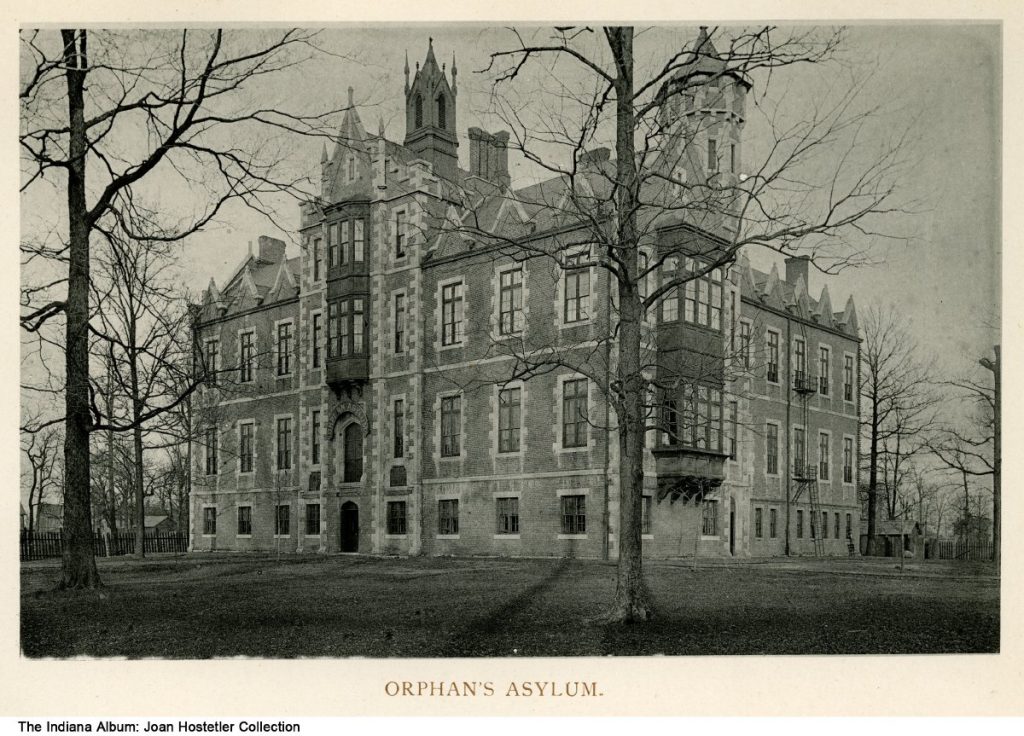

As Indianapolis began to return to normal, the damage was assessed. On November 24, 1918, the Indianapolis Star tallied the state’s loss at 3,266 Hoosiers, mostly young men and women. This massive loss of citizens in their prime left 3,020 children orphaned. The War Department also assessed the losses at Fort Benjamin Harrison. The Surgeon General reported that General Hospital 25 at the fort treated a total of 3,116 cases of influenza and 521 cases of related pneumonia. The hard work of the medical staff and brave volunteers transformed a fort designed to care for a few hundred injured men into a giant hospital caring for thousands.

The city also benefited from leadership of the committed men of Indianapolis and the State Board of Health, as well as cooperative citizens. According to the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine, “In the end, Indianapolis had an epidemic death rate of 290 per 100,000 people, one of the lowest in the nation.” The center attributes the city’s relative success to “how well Indianapolis as well as state officials worked together to implement community mitigation measures against influenza,” whereas in other cities “squabbling among officials and occasionally business interests hampered effective decision-making.” Indianapolis leaders presented a united front, shop and theater owners complied despite personal loss, and brave men and women volunteered their services at risk to their own lives. Somehow only one of the heroic volunteer nurses stationed at Fort Benjamin Harrison lost her life.

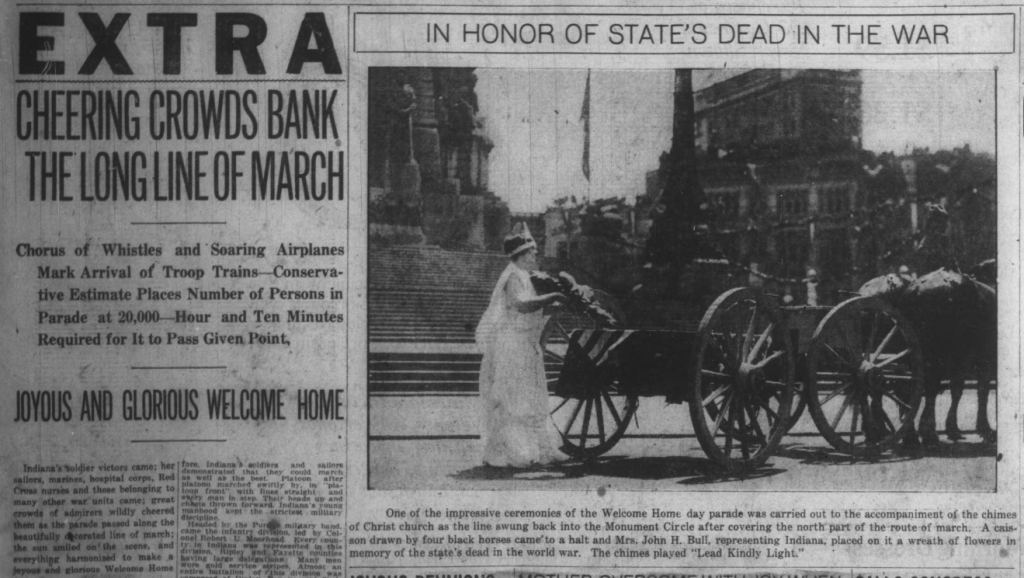

On May 6, 1919, the Indianapolis News replaced columns of text detailing the influenza-related losses with jubilant articles about the city’s preparations for Welcome Home Day. Trains unloaded Hoosier soldiers still carrying their regimental colors. Indianapolis decked herself out in red, white, and blue. On May 7, 1919, 20,000 men and women walked in the welcome parade that stretched for 33 blocks. Many, like the men and women of Hospital No. 32, trained and mobilized at Fort Benjamin Harrison. Many had survived the Spanish Influenza, nursed the sick, or lost a friend to the pandemic. Not a single article mentioned it. The city was ready to move towards peace and healing.

For further reading and linked resources:

“Guns, Germs, and Indiana Athletics, 1917-1920: How Did the Great War and the Great Pandemic Affect Indiana Sports,” Blogging Hoosier History.

Influenza Encyclopedia, University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine