Legendary choreographer and “unsung gay hero” Charles Allen sat with a tape recorder in his Fort Wayne house, a veritable art museum awaiting curation. Sipping gin and orange juice from an empty peanut butter jar, he began to document his life. Notorious for self-mythologizing—once claiming to have killed a man using “voodoo and black magic”—some of the anecdotes he fed the tape no doubt were embellished.[1] These would prove unnecessary, however, as his legacy speaks for itself. Not only did Allen give “birth to generations of dancers and . . . change the way people looked at the world around him,” but he inspired and empowered LGBTQ+ Hoosiers, perhaps unintentionally. Upon Allen’s 1980 death, Jerry Jokay wrote in TROIS, Fort Wayne’s gay newsletter, that “Although he probably wouldn’t have seen it this way, one of his greatest contributions was that he was a gay hero. And he is a gay hero simply because his gayness was a trivial issue in his life even in spite of the oppression it caused him.”[2] Allen, on the other hand, would probably consider his greatest contributions to be advancing performing arts and instilling a love of storytelling and self-expression in Hoosiers.

Born in 1912, Allen was likely raised by his aunt and uncle in Mongo, Indiana. Depictions of Allen’s childhood are characteristically colorful and include a traipse through Tamarack Swamp with famed author and naturalist Gene Stratton Porter in search of insects and plant specimens.[3] Allen “recalled dyeing his hair pinkish-brown as a child, catching blue racer snakes, putting them around his neck, and startling passersby on highway 20 near his home. A barefoot, innocent, wild-haired child of the swamp.”[4] The spirited child attended school in Kendallville and spent free time in LaGrange, where he learned to play piano at Wigdon Theater. Fully enamored with artistic expression, he devoured performances delivered by a travelling company. The News-Sentinel reported “there was a troupe of four or five men, who did a two-reel silent movie, and set up an impromptu stage with an indian scene. There was singing, and two of the men did female impersonations. When he left the show, his life had changed. . . . He’d fallen in love.”

The production continued to call to him, long after the caravans departed. He left school, took a train to northern Michigan, where the travelling company had migrated, and became its new pianist. As despair deepened during the Great Depression, the public increasingly took solace in travelling shows. These provided Allen with opportunities to try his theatrical hand and hone his skills as a performer. The News-Sentinel noted, “People were doing almost anything for money. He fell in with a freak show,” dubbed the Palace of Wonders, for which he mesmerized crowds as the Human Pin Cushion. During this period, Allen learned how to perform the “half-man, half-woman” act, styling his feminine half after screen siren Marlene Dietrich. When he returned to Fort Wayne, he would perform this routine at local tavern, Henry’s, and played piano at bars like This Old House, Trolly Bar, and the Caboose.[5] Allen insisted that friends stay at his house once the bars closed down for the night, hating solitude.[6]

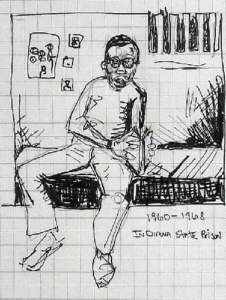

The eclectic career he had forged for himself was abruptly derailed by the conformist ethos of the 1940s. At a time of global upheaval, Americans held evermore sacrosanct heteronormativity. The News-Sentinel reported that during this “less enlightened age,” a judge sentenced Allen to six years in a Michigan City Prison after “an affair with a soldier led to a charge of sodomy.”[7] Allen recalled in the Fort Wayne Free Press that the judge declared ironically “we’re going to send you where you’ll be happy; locked up with a lot of men!”[8] This prediction proved correct, as he spent time with paramours in a makeshift room fashioned out of old pianos and curtains. On weekends, he played piano for the men waiting in line to watch a movie. While it played, a band mate would take his place at the piano, so that he could go hold hands with his companion. During his few years in prison, Allen made friends, assembled a band—for which he played the sousaphone—and learned how to dance.[9]

The News-Sentinel noted that in prison Allen “kept following his insatible [sic] desire to learn. Where he could find no one else to teach him, he taught himself. The creativity could never let him rest. It would be that way to the end of his life.”[10] This cultivation of self-expression paralleled the journey of African American poet, Etheridge Knight. While serving eight years at the Indiana State Prison in the 1960s, he discovered the restorative power of writing, culminating in his revolutionary Poems from Prison. Knight later stated that “Poetry and a few people in there trying to stay human saved me . . . I knew that I couldn’t just deaden all my feeling the way some people did.”[11]

So, too, did music and dance sustain Allen during his incarceration. Upon release, he returned to Fort Wayne, opening the Charles Allen Dance Studio.[12] According to the Journal-Gazette, he was the city’s only choreographer and, through his trips to New York and Chicago, “single-handedly” invigorated the city’s theater scene. Something of a cultural conduit, Allen traveled to Vera Cruz, Mexico to research indigenous dances. He studied dance at the University of Guatemala and the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico, imbuing midwestern students with unique material and perspectives.[13]

In life and work, Allen gravitated towards those on the fringes, perhaps identifying with their struggles or the stigmatization they endured. He reportedly taught exotic dancers how to improve their performances and played piano at “houses of ill repute.”[14] In his TROIS article, Springer wrote that Allen played piano and felt a “kinship” with Black Americans because “like him, they were among the outsiders of society.”[15] Though he was exacting and sometimes cruel, the News Sentinel reported that “he would work with beginners no one else had time for, work tirelessly because he felt a love of what he was doing.”[16] Janice Dyson recalled this experience, after her mom “scrimped grocery money to help pay” for lessons for her and her sister, Bernice. She recalled that Allen “was a real taskmaster. . . . Bernice was intimidated by him and quit after about a year. I wasn’t afraid of him, but I learned pretty quickly that when he said practice or else, he meant it.”[17] Perhaps he hoped to provoke the same grit he’d developed through surmounting the many hardships imposed by society.

While he worked with Fort Wayne performers, Allen reportedly knew the jazz greats, like Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong, and one friend noted that “a lot of famous people used to come here and have him fix their acts. Polish the acts. Reblock them or rechoreograph them.'”[18] Legend has it that one winter Allen sold his horse to pay the train fare to see Holiday perform in New York City. Due to a snow storm, he was the only person to show up at the theater. The usher relayed his presence to Holiday, who performed only for him, after which they went out for a drink. She reportedly drove him to the train station and ran alongside the cars, waving as the train departed. Allen was so moved by the experience that he wept while watching the train station scene in “The Lady Sings the Blues.”[19]

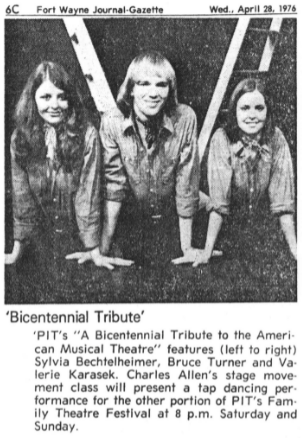

Purdue University Fort Wayne (PUFW) recognized the ingenue’s talent, hiring Allen to teach courses like Stage Movement.[20] He felt immense pride about being self-taught. A man who embodied resistance towards oppression and convention, his influence intersected fortuitously with the cultural revolution of the late 1960s and 1970s. Friends and colleagues seem to agree that he was not an activist in the traditional sense, but he always answered when called to provide insight about homosexuality or the burgeoning “homophile” movement. He recognized that, as one of few men in the area living openly, if he did not engage in public discourse that no one one would. When asked by WANE-TV to serve as one of five panelists about homosexuality Allen agreed, saying “‘I’m all right here, I don’t have any problems because I’m not scared. But a lot of people are scared; they’re scared they’ll get arrested.”[21] He appealed to dozens of people to serve as panelists, but only two agreed. Those who declined feared that their parents would disown them or that they would lose their job, as had one of Allen’s friends who served in World War II. Others claimed the panel was unnecessary or worried that it would upset the “status quo,” which had provided a modicum of safety. To this reasoning, Allen said, “‘I thought if everything is so fine, why can’t they get on the air and say it’s fine. It’s because it isn’t fine.”[22]

Allen spoke about homosexuality at PUFW campus teach-ins and college classes, and wrote editorials for the student paper, The Fort Wayne Free Press, under the pseudonym “Claude Hawk.”[23] He wanted audiences to understand that sexuality was not a choice, noting that “My own doctor tells me that one gene or chromosome determines sexual preference—not butchness, effeminancy, athleticism, not militancy, but whom you want to go to bed with.”[24] He added that this knowledge, while “comforting,” doesn’t help if you get fired or the “bartender breaks your glass after each drink, etc., etc.” His efforts shifted the perspectives of students like Linda Lamirand and Katharine Stout, who attended a teach-in with the “brave man” who “sat up there and told it like it is.”[25] The authors were enlightened by Allen’s revelations that he knew he was gay at the age of four and that scientific studies suggested that biology dictated sexual preference.

In one Free Press editorial, Allen addressed those who had come to terms with their sexuality, but faced the question “where do you go?” to meet someone. Of the dilemma, he wrote:

You can’t find someone at an office party or at a neighborhood bar because someone would ‘find out’. So you experiment. You drink too much or get so horny that, without experience, you get your teeth bashed in saying something dumb to to the wrong person; or the right-wrong person who relieves you of your watch, wallet, and rings. Or sometimes you are picked up by a nicelooking, intelligent, young man with long hair and bare feet, who turns out to be fuzz and you are entrapped, fined, and-or jailed.[26]

He advised readers to find a “gentle, gay” friend, who can help navigate the covert social world, or a relatively tolerant restaurant or bar. A “third salvation,” Allen noted, was to “know an art or theater crowd who don’t give a damn. Not about you, but about it.” The theater provided a world in which he did not have to explain himself or act as a local spokesperson for homosexuality. He wrote that the “freedom, acceptance, and love” afforded by the theater community created “a place to breathe in this pollution of brotherhood. Since one doesn’t have to hide, or lose his job in these fields, these are the more obvious” ones in which to work.[27] In fact, Allen noted that living as a gay man paralleled life in the performing arts, writing:

“You are forced to think and live like a male and play the game so well that you are never uncovered. And this becomes an art, gives you a facility for understanding objectively what’s going on. It’s like a play, and while others are doing it naturally you’re listening for clues, and if well rehearsed, arrive at a happy ending.”[28]

While TROIS writer Jerry Jokay considered Allen “Fort Wayne’s unsung gay hero,” he noted that “his fortitude laid in the fact that he didn’t dwell upon his difference . . . Allen was preoccupied with being so much more, as his best friends attest.”[29] Preoccupied, he was. Allen informed Free Press readers about his life, writing in 1971 that “I ran my own school, taught at Purdue, played piano in bars, was connected with Ft. Wayne Civic Theater, Kenosha Little Theater, Theater Alanta, had choreographed a Broadway show, was a Japanese paper folder, an Arabian knot tier.”[30] He had traveled the globe in search of inspiration and imbued new generations of performers with it. The News-Sentinel wrote that “he became unique, in a world of his own creation. His art became his life, his life his art.”[31]

His life, his art. Perhaps it was his cancer diagnosis that inspired him to detail them on tape, stories that writer Dan Luzadder suggested “may have been plucked from the intensity of his nether world.”[32] We don’t know what stories he told, as he ran out of time to complete the recordings,* but perhaps he described the demands of caring for his pet python or recited original sonnets, haikus, and Limericks, “both clean and questionable.”[33] We can be certain that his life and art profoundly influenced those around him. This is evidenced by the obituaries written upon his death in 1980 at the age of 68. Luzadder wrote in the Fort Wayne News-Sentinel:

There was loneliness and insecurity. There were things that drove him. And there was tremendous courage to live through the times of his life, to aspire to art, to survive with nothing more than intelligence and faith in himself, to go hungry, to be alone, to see the world in its intolerance and still love it.[34]

On March 21, hundreds of people from all walks of life—including actors, dancers, bartenders, city officials, and editors—stood shoulder-to-shoulder at the Performing Arts Center to pay their respects to the man “whose life had taught them the meaning of art.”[35] His memorial served as a final standing ovation, with Civic Director Richard Casey reading from “Hamlet,” poets performing spoken word, and dancers delivering a finale performance of “Mr. Bojangles.”[36]

Allen provides us with a window into the experiences of those who lived openly in Indiana prior to the liberating events of the 1980s and 1990s. Before a sense of community was fostered by the formation of groups like Fort Wayne Gay and Lesbian Organization (GLO), Pride Week celebrations, and the publication of gay newsletters, Allen drew upon a deep reservoir of self-assurance and creative impulse to fashion a fulfilling life.[37] In his 1980 tribute, Steve Springer described Allen as “an individualist. Society had its standards of behavior and Allen had his own.” And although he had suffered because of these standards, Springer insisted that “Long after Anita Bryant and her hordes of intolerants are forgotten, the legend of Charles Allen will live on.”[38]

* The author has been unable to locate these recordings. If you know of their location please contact npoletika @library.in.gov.

Sources:

All issues of The Fort Wayne Free Press were accessed via mDON Mastodon Digital Object Network, Helmke Library, Purdue University Fort Wayne.

[1] Dan Luzadder, “Charles Allen: His Life and His Art Were his Epitaph,” (Fort Wayne) News-Sentinel, March 21, 1980, 7A, Indiana State Library (ISL) microfilm.

[2] Jerry Jokay, “Who Was Charles Allen?,” TROIS (Three Rivers’ One in Six) (March 1983), Northeast Indiana Diversity Library Collection, accessed Indiana Memory.

[3] “Arts Center Site for Allen Service,” (Fort Wayne) News-Sentinel, March 20, 1980, ISL microfilm.

[4] Dan Luzadder, “Charles Allen: His Life and His Art Were his Epitaph,” (Fort Wayne) News-Sentinel, March 21, 1980, 7A, ISL microfilm.

[5] Dell Ford, “Artists’ Artist Charles Allen Dies,” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, March 20, 1980, 1C, 2C, ISL microfilm.

[6] Dan Luzadder, “Charles Allen: His Life and His Art Were his Epitaph,” (Fort Wayne) News-Sentinel, March 21, 1980, 7A, ISL microfilm.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Claude Hawk, “Boys Will Be Girls!,” The Fort Wayne Free Press 2, iss. 1 (January 1, 1971): 3.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Dan Luzadder, “Charles Allen: His Life and His Art Were his Epitaph,” (Fort Wayne) News-Sentinel, March 21, 1980, 7A, ISL microfilm.

[11] Nicole Poletika, “Etheridge Knight: ‘can there anything good come out of prison,'” May 3, 2017, accessed Untold Indiana.

[12] Steve Springer, “Chas. Allen,” The Communicator, March 27, 1980, reprinted in TROIS (Three Rivers’ One in Six) (May 1980): 5, 7, Northeast Indiana Diversity Library Collection, accessed Indiana Memory.

[13] Dell Ford, “Artists’ Artist Charles Allen Dies,” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, March 20, 1980, 1C, 2C, ISL microfilm.

[14] Ibid.; Dan Luzadder, “Charles Allen: His Life and His Art Were his Epitaph,” (Fort Wayne) News-Sentinel, March 21, 1980, 7A, ISL microfilm.

[15] Steve Springer, “Chas. Allen,” The Communicator, March 27, 1980, reprinted in TROIS (Three Rivers’ One in Six) (May 1980): 5, 7, Northeast Indiana Diversity Library Collection, accessed Indiana Memory.

[16] Dan Luzadder, “Charles Allen: His Life and His Art Were his Epitaph,” (Fort Wayne) News-Sentinel, March 21, 1980, 7A, ISL microfilm.

[17] Janice Dyson, “Studio Marks 65 Years of Dancing,” KPC News, December 28, 2017, accessed kpcnews.com.

[18] Dell Ford, “Artists’ Artist Charles Allen Dies,” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, March 20, 1980, 1C, 2C, ISL microfilm.

[19] Steve Springer, “Chas. Allen,” The Communicator, March 27, 1980, reprinted in TROIS (Three Rivers’ One in Six) (May 1980): 5, 7, Northeast Indiana Diversity Library Collection, accessed Indiana Memory.

[20] “Family Festival Slated,” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, April 28, 1976, 6C.

[21] “It Isn’t Fine,” The Fort Wayne Free Press 2, no. 17 (September 9-23, 1971).

[22] Ibid.

[23] Claude Hawk, “Wherever You Are!,” The Fort Wayne Free Press 1, iss. 10 (October 7-21, 1970): 4.; Claude Hawk, “Out of the Closet,” The Fort Wayne Free Press 1, iss. 11 (November 2-18, 1970): 3, 6.; “It Isn’t Fine,” The Fort Wayne Free Press 2, no. 17 (September 9-23, 1971).

[24] Claude Hawk, “Wherever You Are!,” The Fort Wayne Free Press 1, iss. 10 (October 7-21, 1970): 4.

[25] Linda Lamirand and Katharine Stout, “Dear Freep,” The Fort Wayne Free Press 2, iss. 7 (April 22-May 6, 1971): 10.

[26] Claude Hawk, “Wherever You Are!,” The Fort Wayne Free Press 1, iss. 10 (October 7-21, 1970): 4.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Claude Hawk, “God Love Us All,” The Fort Wayne Free Press 2, iss. 8 (May 6, 1971): 9.

[29] Jerry Jokay, “Who Was Charles Allen?,” TROIS (Three Rivers’ One in Six) (March 1983), Northeast Indiana Diversity Library Collection, accessed Indiana Memory.

[30] Bob Ihrie and Charles Allen, “Holiday on Ice,” The Fort Wayne Free Press 2, iss. 2 (January 18-February 2, 1971): 3.

[31] Dan Luzadder, “Charles Allen: His Life and His Art Were his Epitaph,” (Fort Wayne) News-Sentinel, March 21, 1980, 7A, ISL microfilm.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Dell Ford, “Artists’ Artist Charles Allen Dies,” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, March 20, 1980, 1C, 2C, ISL microfilm.

[34] Dan Luzadder, “Charles Allen: His Life and His Art Were his Epitaph,” (Fort Wayne) News-Sentinel, March 21, 1980, 7A, ISL microfilm.

[35] Dell Ford, “Funeral Celebrates Dance, Poetry, Drama, Music,” Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, March 22, 1980, C1, ISL microfilm.; Steve Springer, “Chas. Allen,” The Communicator, March 27, 1980, reprinted in TROIS (Three Rivers’ One in Six) (May 1980): 5, 7, Northeast Indiana Diversity Library Collection, accessed Indiana Memory.

[36] Dell Ford, “Funeral Celebrates Dance, Poetry, Drama, Music,” Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, March 22, 1980, C1, ISL microfilm.

[37] Nicole Poletika, “From ‘Gay Knights’ to Celebration on the Circle: A History of Pride in Indianapolis,” October 5, 2021, accessed Untold Indiana.

[38] Steve Springer, “Chas. Allen,” The Communicator, March 27, 1980, reprinted in TROIS (Three Rivers’ One in Six) (May 1980): 5, 7, Northeast Indiana Diversity Library Collection, accessed Indiana Memory.