The only effort I ever made was to state on divers[e] occasions that I was not a member of the Klan.

– Samuel M. Ralston, 1924

Late in Ralston’s career as a Democratic politician in the 1920s, his party had to take a stand on the issue of the Ku Klux Klan‘s political influence. Would Democrats in Indiana and the country cater to the secret organization for their vote or disavow them as counter to the very principles of democracy? With individual exceptions, the party chose the later, albeit feebly, inserting an anti-Klan plank in their platform at the state and national level, without calling out the organization by name.

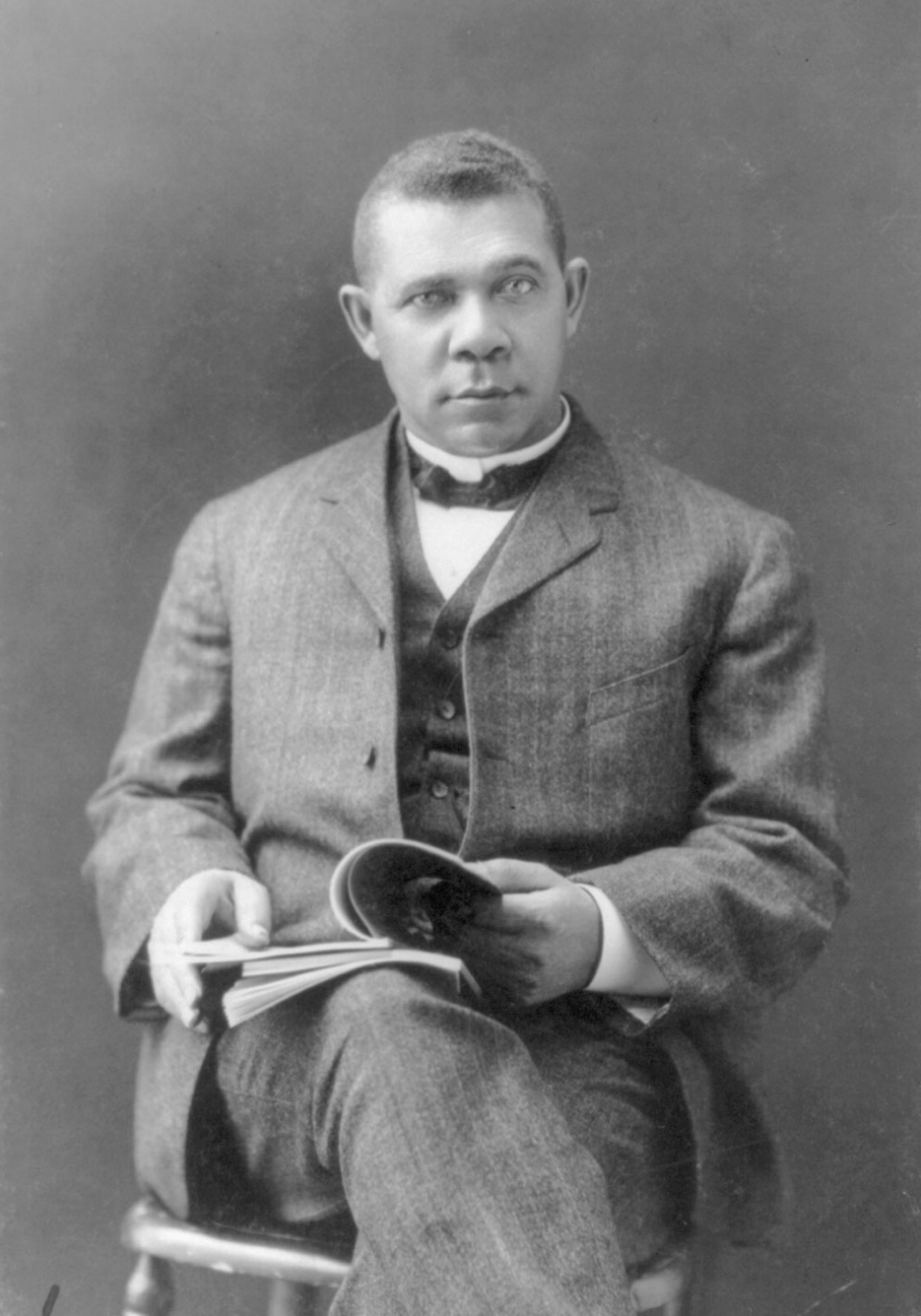

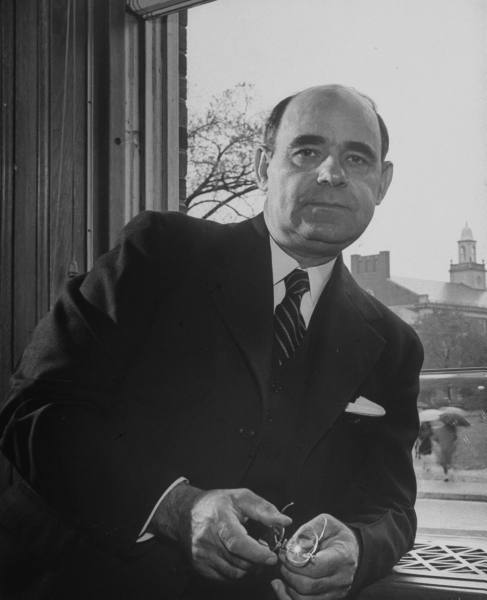

When questioned, Ralston consistently and repeatedly denied any affiliation with the Klan. Nonetheless, modern secondary sources continue to link his name with Klan influence, especially in relation to his 1922 U.S. Senate race. However, these sources charge Ralston with the wrong transgression. If Ralston was guilty of anything, it was not for being a Klan member or seeking Klan political support. Rather, he attempted to remain neutral when the Klan threat to immigrant, Catholic, Jewish, and African American Hoosiers demanded clear and bold moral action. This issue from his later career is worth examining in a more nuanced manner as we prepare to dedicate a new state historical marker to his earlier legacy as governor of Indiana.

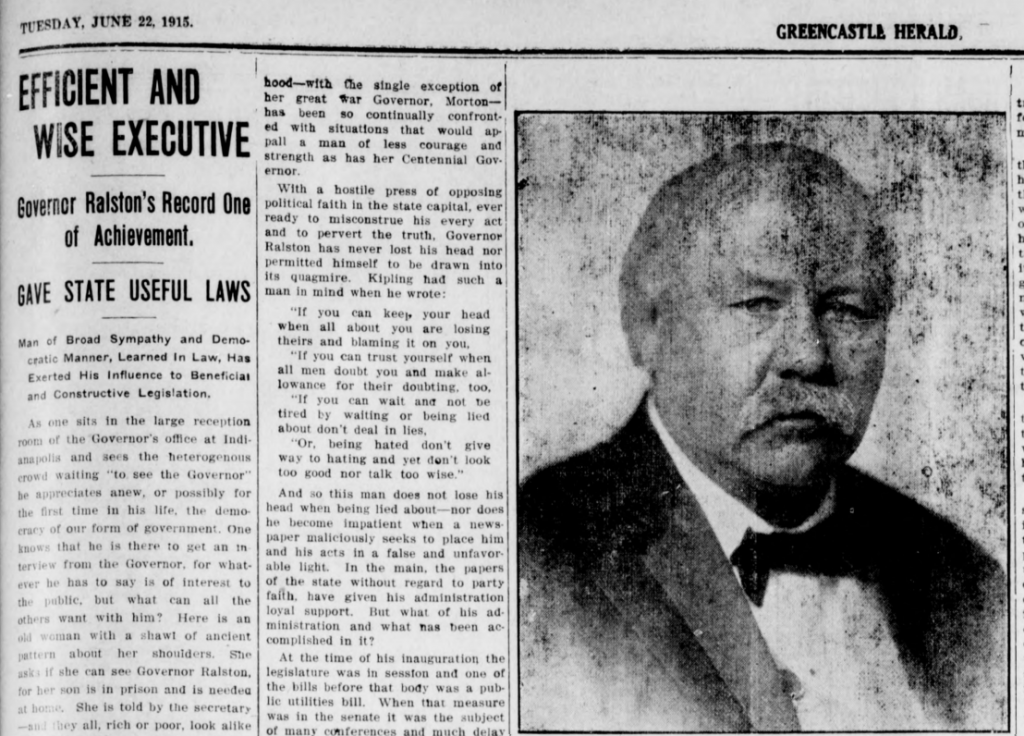

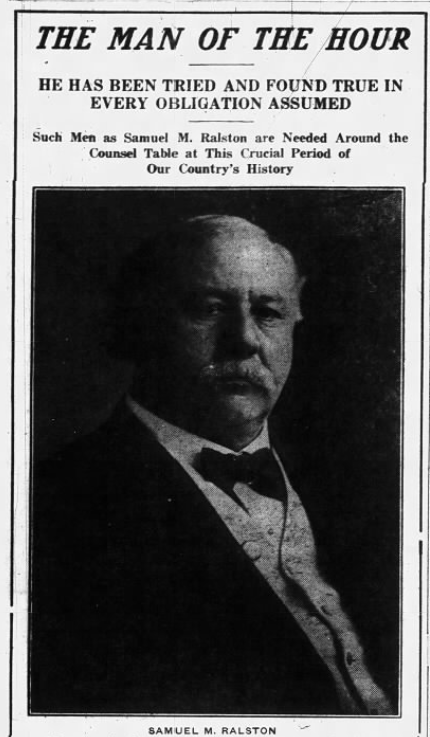

Ralston the Governor

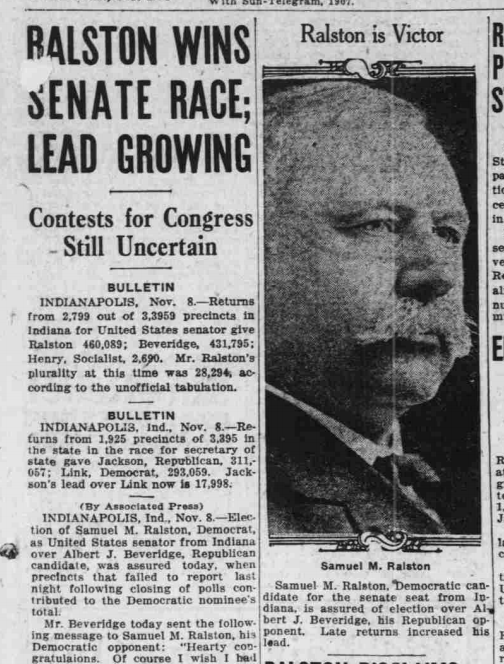

Samuel M. Ralston could be classified among the more progressive of the candidates who swept the 1912 state elections. Such a political leaning helped him defeat Progressive Party nominee Albert J. Beveridge, his closest gubernatorial challenger. The Progressive Party, or Bull Moose, were a third party of Republicans led by ex-President Theodore Roosevelt who challenged the political status quo. GOP gubernatorial nominee and former Governor Winfield T. Durbin came in third in the 1912 election.

Once in office, Ralston worked for many of the reforms advocated by the Progressive Party, albeit at a moderate pace that did not rock the Democratic Party boat. According to historian Suellen M. Hoy, Ralston’s publicly-declared progressive measures included: women’s suffrage, workmen’s compensation, better roads, improved vocational education, more humane prison conditions, and a child labor law, among other issues.

His concern for the average Hoosier’s welfare was evidenced in his advocacy for the creation of a public utilities act, which redefined utilities as being both publicly and privately owned and thus rightly regulated by citizens through their government agencies. His concern was also apparent in his swift and unrelenting action in organizing emergency relief in response to the Great Flood of 1913. Later that same year, he personally helped negotiate a resolution to a strike organized by streetcar workers that had turned violent.

Klan Allegations in Historical Sources

However, Ralston’s progressive legacy has been overshadowed by his alleged association with the Ku Klux Klan during his 1922 United States Senate campaign. This taint on his legacy seems to stem in part from an oft-quoted sentence from David M. Chalmers’ 1965 work Hooded Americanism. Chalmers wrote about the 1922 election:

The Klan’s most notable effort was its role in sending Samuel M. Ralston, to the Senate.

Chalmers’ source for this claim is a talk Ralston gave at St. Mary of the Woods, a Catholic women’s college in Terre Haute. In his address, the candidate spoke in part about “the importance of religious liberty and the separation of Church and State.” It is important to remember that in 1920, Indiana’s African American population was less than 3% of the total. Much of the Indiana Klan’s rhetoric and actions were directed to the more sizable Catholic populations. In reaction to this speech, Chalmers wrote that “the Klan was delighted.” Chalmers continued: “Here was a man who was not afraid to tell the papists off to their very face.” Chalmers argued for his interpretation, “Backed by the Klan . . . Ralston won.”

Chalmers is correct that the Klan endorsed Ralston’s candidacy. However, their support came not from Ralston’s actions, but his inaction, or neutrality, on the Klan issue. Retrospectively, this was not an admirable position. However, Chalmers overemphasizes any direct connection between the senator and the Klan.

The Klan in Context

The Klan was politically active in Indiana by the 1920s. Infamous Klan leader D. C. Stephenson claimed to have some measure of control of the votes of 380,000 Klansmen. He explained that his followers would receive sample ballots with a Klan-approved choice marked for both political parties – a Democrat and a Republican candidate favorable to, or at least not opposed to, the Klan. Eventually, Stephenson released the names of several prominent Indiana politicians who were Klansmen, including the Governor Ed Jackson and Mayor John L. Duvall of Indianapolis.

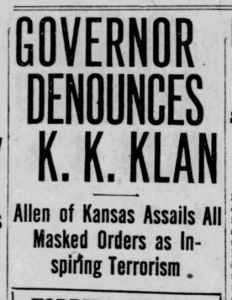

However, as historian Joseph M. White argues, the Klan’s “actual political power should not be overdrawn.” According to White, while the Klan had “a high level of influence” on Indiana politics, it never achieved the “outright control” that it did in other states. For example, in Georgia, Tom Watson gained his U.S. Senate seat in 1920 “using the supposed threat of Catholicism as the principle issue.” Ralston, on the other hand, mainly ignored the Klan in his 1922 bid for the Senate. While he did not cater to the secret organization, he also did not denounce it as other state leaders did. For example, Kansas Governor Henry J. Allen spoke at Richmond, Indiana, in October 1922 where he “flayed the Ku Klux Klan,” according to the Indianapolis News.

According to historian Thomas Pegram in his book One Hundred Percent American, the Klan was better at “targeting enemies” than it was at gaining politicians’ support for their desired policies. This was certainly true in Indiana. The Klan did not win the open support of any major Democratic candidates. Instead, it acted against the election of Republican U.S. Senate candidate Albert Beveridge for “various aspersions uttered by him about ‘groups’ and ‘racial prejudice’ [that] were taken by the Klan as occasion for passing the word to vote against Beveridge,” according to the Richmond Palladium. Stephenson himself stated that it was the aforementioned anti-Klan speeches that Governor Allen made in support of Beveridge that turned Klan support toward Ralston – not any specific action or position of Ralston.

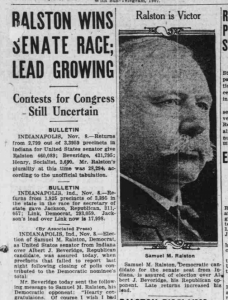

On November 8, 1922, Indiana newspapers announced Democratic Party gains nationwide, including the election of Ralston to the United States Senate. The extent to which his neutrality on the Klan issue helped his win is difficult to determine. What is clear, is that Ralston, once in office, did nothing to further any Klan-favorite legislation during his term. His position would become clearer as the 1924 elections drew near.

Democratic Neutrality

Indiana Democrats under the influence of political boss Thomas Taggart attempted to stay neutral on the Klan, neither courting their support nor directly denouncing the organization throughout the early 1920s. According to historian Leonard J. Moore in his book Citizen Klansmen, the party strategized that this neutrality would “deemphazise the Klan as an issue” allowing them to “attack the Republicans at their weakest point — corruption in both Indianapolis and Washington.”

However, the party and Ralston, soon had to take a clearer position.

Ralston’s Denial

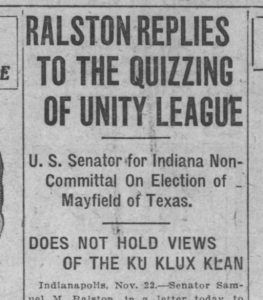

In November 1923, Indiana newspapers reported on Ralston’s response to questions on his relationship to the Klan from the Marion County branch of the American Unity League, a mainly Catholic organization working to unmask Klan members and thus obstruct their secret agenda. Most Indiana newspapers reprinted his letter in full on their front pages.

The League asked six questions in their letter. The first three addressed a petition filed against U. S. Senator from Texas, Earle B. Mayfield, by his opponent in the 1922 election, George E. B. Peddy. According to the U. S. Senate’s summary of the case, Peddy alleged that Mayfield benefited from the “use of fraudulent ballot counting procedures, excessive expenditure of money, and the flagrant participation of the Ku Klux Klan.”

The League asked Ralston if he thought Mayfield’s Klan association was “consistent with loyalty to the laws and constitution of the United States;” if Mayfield was worthy of his Senate seat while charged with receiving “vast sums of money” from the Klan; and if Ralston would vote for Mayfield to keep his seat “when the question comes up before the Senate.” Ralston responded that he would not “pre-judge” anyone before a hearing and that doing so would “be a gross violation of official duty, and would render me unfit to hold a seat in the Senate.” He continued:

Certainly your love for justice is such that it would shock you to know that I had deliberately taken on a frame of mind that would render it impossible for me to give Senator Mayfield a fair and impartial hearing.

Ralston moved on to the League’s fourth question: “Are you a member of the Invisible Empire of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, or of the organization known as the Royal Order of Lions, which is affiliated with the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan?” Ralston replied, “I am not now, and never have been, a member of either organization.” He added that he was a Mason, an Elk, a Presbyterian, and a Democrat.

The League’s fifth question read: “Do you believe in the officially announced program of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan which openly declares that Jews, Catholics, negroes and foreign-born citizens of the United States are not 100 per cent American, and should be discriminated against on account of race, creed, color or birthplace?” Ralston responded:

My answer is that I hold no such view of these people, as a class, and if you had followed me in my campaign for the Senate you would know that I do not.

The League ended with a sixth question: “Finally, are you for the constitution of the United States and the ideals of the American republic, or for the announced principles of the Ku Klux Klan and the invisible empire?”

Ralston called the question “an insult” and gave an extensive response:

I do not believe that the Ku Klux Klan, or any civic organization has announced principles and ideas the equal of those set forth in the constitution of the United States . . . I have never failed, when it was seemly for me to mention the subject, to declare my unabated devotion of our Federal constitution, which provides for the separation of Church and States, and guarantees to every man the right to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience . . . I shall in the future, as I have in the past, stand ready to oppose the promulgation of any principle of the Ku Klux Klan, or of the Presbyterian church to which I belong, or of any Jewish organization to which you may belong, or of any other character, that is at war with [the constitution].

Neutrality as Complicity

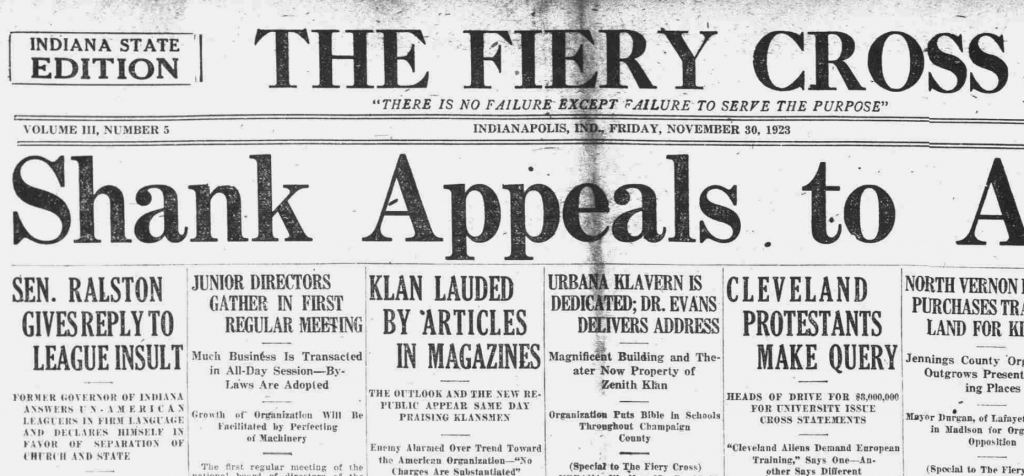

Finally, Ralston had made a strong statement disavowing any association with the Klan. However, the Fiery Cross, a Klan newspaper published in Indianapolis, also reprinted Ralston’s letter in full. It might seem strange that the Fiery Cross published a denunciation of their organization by a politician they had supported. However, they may have felt they benefited from Ralston including the Klan in a list with major groups and religions, including his own, thus normalizing their movement to some extent.

On June 26, 1924, at the Democratic National Convention in New York, Senator Ralston, despite his objections, was one of nineteen candidates nominated for the presidency of the United States. The convention was one of the most contentious political conventions in U.S. history (and no it really was not called the “Klanbake.”)

After eighty-eight ballots it started to look like the convention was swinging towards Ralston, the supporters of New York Governor Al Smith’s nomination, including the New York World, attempted to link Ralston with the Klan issue. The story quickly gained traction during a quick-paced convention that didn’t have a clear front-runner or consensus candidate. The Indianapolis Star printed daily reports from their correspondent in New York. On June 28, the Star reported that “in a last-hour effort to kill off the Ralston candidacy which has been in its ascendancy for the past two days, the New York World, the Al Smith organ,” printed a story claiming that the Klan supported Ralston even more than William Gibbs McAdoo, who had catered their support.

The following day, the Star reported that Ralston was “nettled” by the New York World‘s charges, “emphatically denied allegiance with the Klan, and denounced persons who attempted to link his name with it.” The Star quoted Ralston:

You can say for me that any one who says or intimated that I am a klansman is a ‘liar,’ and you can put that on the wires too.

The Star reported that “Ralston declared that he could not understand the attitude of the World, saying that he had already emphatically stated his position on the Klan question, and that there should be no further question as to where he stood.” He reiterated that “he had never sought the vote of any klansman, that he was not a klansman or in any way affiliated with the organization.” Instead, the Star reported, he would “appreciate the votes of all citizens regardless of race, creed or belief, provided that the support was given him with the full understanding that he would stand squarely on the platform of the Democratic part and the constitution of the United States.”

As he did (wittingly or not) in his response to the American Unity League, his grouping the Klan in with a “creed or belief” assimilated the extremist organization into the standard pool of voters. In fact, in his response to the World, he drove this message home. The Star quoted Ralston:

I never asked a klansman to vote for me. I never asked a Jew or a Catholic to vote for me. I never asked any one to vote for me for President . . . But if I am nominated and elected I will try to give a good, honest Democratic administration. Jew, Catholic and klansman will be treated alike in full recognition of the constitutional rights guaranteed every citizen.

What Ralston did not or did not choose to see, of course, was that there was no democracy for Catholics and Jews as long as the Klan was tolerated by men in power. His statement to the convention attendees was more succinct. Ralston wrote again that he was “not a member of the Klan or any of its branches” and continued:

If nominated, I shall stand on the platform of the New York convention and insist upon every citizen having his constitutional rights safeguarded.

The New York World took one final shot at Ralston on July 2, printing the claims of attorney Claude V. Dodson of Boone County, Indiana, where Ralston also lived and practiced law for much of this career. Dodson told the New York World that he “to my shame” was at one time a member of the Boone County Indiana Klan, which had been organized in that region in 1923 by P. B. Ramsey. Dodson described one of Ramsey’s recruiting tactics:

These organizers told members of the Klan after their initiation that Samuel M. Ralston was a member of their organization. He also told prospective members in some instances that Senator Ralston was a member in an effort to gain the prospect as a member.

Dodson agreed that any claims that Ralston was a member of the Klan were indeed false. However, he and the New York World thought that Ralston should have forthwith and publicly denied the unauthorized use of his name, and denounced the Klan as an “unAmerican organization” in his hometown. Dodson continued:

I will say frankly that the Klan claim as to Senator Ralston’s membership should have little weight or credence, because most of the Klan claims are false, but in this instance, Senator Ralston’s attention was called to this matter more than a year ago. He was informed that his name was being used by the Klan organizers, and no doubt it influenced many people to join the Klan . . . At that time Senator Ralston did not avail himself of the opportunity to inform the people of the state as to the truth of falsity of the Klan claim; neither did he show any anger publicly toward Klan organizers for using his name. It was only when those opposed to the Klan some six months later insisted on a public statement from Senator Ralston as to his attitude toward the Klan and his membership therein that Senator Ralston was insulted . . . Senator Ralston’s statement that he stands on the constitution . . . is well and good, but we who are opposed to the Klan ask Senator Ralston to come out and state flatly, calling the Klan by name, what his attitude is toward that organization and its principles.

Ralston responded tepidly to these charges, continuing to disavow membership without actually condemning the Klan:

To what extent the Klan or any other organization runs counter to the constitution of my country I am against it.

The World reported that when “asked what efforts he had made to prevent the Klan from using his name to obtain new members,” Ralston reiterated:

The only effort I ever made was to state on divers[e] occasions that I was not a member of the Klan.

Several days later, Ralston withdrew from the race. Although to be clear his withdrawal was due to poor health, and not being interested in running for national office (his supporters had promoted his candidacy against his will). The Klan rumors had next to nothing to do with his decision.

Conclusion

In short, Indiana Democrats knew that open support of the Klan would lose moderate votes. However, they also knew it was politically expedient not to have the Klan actively working against a particular nominee. Thus, Ralston chose a course of “emphatic” denial of membership in the secret organization, without denouncing the Klan itself. In fact, he stated that he would treat Klan members no differently than anyone that attended his own church. This implication that they would be left alone was good enough for some Klan members. However, it’s also clear from his record as governor and his reverence for the Constitution that he did care about upholding the rights of women, workers, children, and the incarcerated.

Of course, from our perspective today, we judge those in power who do not act in times of moral crisis as complicit in the related atrocities. Ralston, however, did not have this clear picture of the Klan’s legacy. In the Progressive Era political climate, Ralston walked a middle path that he knew would help him stay in office and effect change on the issues that were important to him. The work of fighting the Klan and working for civil rights would be left to other Hoosiers who had a clearer vision of the threat the secret organization posed to the democracy Ralston loved.

Further Reading

Suellen M. Hoy, “Samuel M. Ralston: Progressive Governor, 1913-1917,” PhD Dissertation, April 1975, Department of History, Indiana University.

Leonard J. Moore, Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921-1928 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991).

Thomas Pegram, One Hundred Percent American: The Rebirth and Decline of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2011).

Joseph M. White, “The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana in the 1920’s as Viewed by the Indiana Catholic and Record,”1975, Master’s Thesis, Butler University, accessed Butler University Digital Commons.