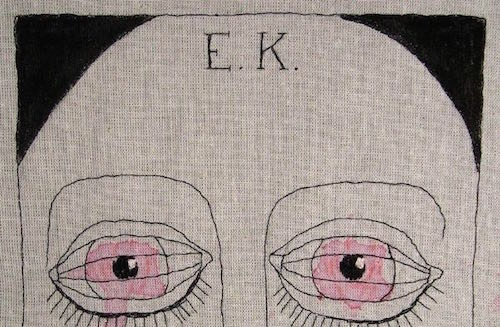

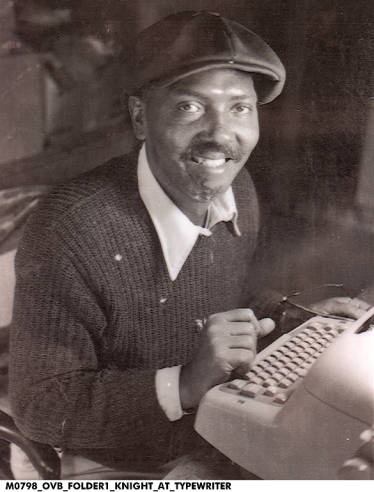

“I died in 1960 from a prison sentence and poetry brought me back to life.” This is how poet Etheridge Knight Jr. described his experience at the Indiana State Prison, where he served eight years for armed robbery. This post focuses on the years 1960-1968, in which the man “with something to say” began sharing his voice through poetry.

Born in 1931 in Corinth, Mississippi, Knight’s family moved to Paducah, Kentucky before moving to Indianapolis. He dropped out of school as a teenager and enlisted in the army in 1947. Knight served as a medical technician in the Korean War until 1950, when a serious injury would indirectly serve as a catalyst for his revolutionary Poems from Prison. His wounds proved so physically and psychologically traumatic that Knight soon developed an addiction to morphine. Or as Knight put it, “I died in Korea from a shrapnel wound and narcotics resurrected me.” Following his army discharge, Knight supported his habit by dealing drugs and stealing, which led to his sentence in the Michigan City, Indiana prison.

Betty De Ramus wrote in the Detroit Free Press that black poets of the 1960s, including those writing behind bars, were not trying to

pass civil rights laws or integrate bathrooms or even to trouble America’s conscience. They were battling for the minds of blacks, bent on persuading them of their potential and power, trying to open them, layer by layer, to their own lost beauty.

She argued that this movement, comprised also of African American music, theater, films, and novels were black artists’ way of “lighting candles in the darkness.” Knight would become a quintessential voice of the Black Arts Movement, described by Larry Neal as “’radically opposed to any concept of the artist that alienates him from his community. Black Arts is the aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept. As such, it envisions art that speaks directly to the needs and aspirations of Black America.’”

Knight did not immediately illuminate the darkness at the Indiana State Prison, where he became embittered by “racist guards and racist parole boards.” According to a 1972 Baltimore Sun article, he began writing poetry 18 months into his sentence, inspired by other black poets like Gwendolyn Brooks (who later visited him in prison) and Langston Hughes. He recalled “I read Walt Whitman and the European poets, too . . . I could never really get to them as I got to Hughes and Brooks.”

According to the Poetry Foundation, Knight “was already an accomplished reciter of “‘toasts'” before he entered the penitentiary. These toasts were long, narrative poems spoken from memory that related to “‘sexual exploits, drug activities, and violent aggressive conflicts involving a cast of familiar folk . . . using street slang, drug and other specialized argot, and often obscenities.'” At the Indiana State Prison, he “toasted,” amidst cell doors slamming and prisoners shouting. Other times, Knight recalled, “Sometimes in the joint . . . I’d back people up against the wall and say, ‘Here, you want to hear this?’ After all budding poets do need an audience, and where better to find one with time to listen?”

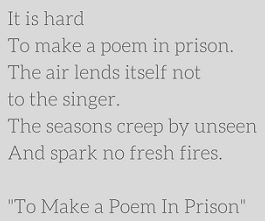

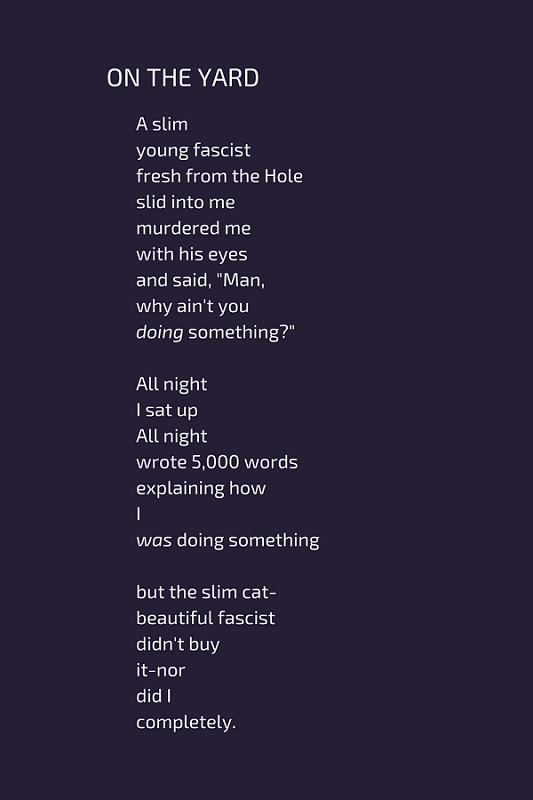

Knight later stated that “Poetry and a few people in there trying to stay human saved me . . . I knew that I couldn’t just deaden all my feeling the way some people did.” This poetry explored themes like “suffering and survival, trial and tribute, loss and love.” The Richmond Palladium-Item reported that through his words he “lashed out at the power brokers in prison and in literature with equal intensity and humor.” At first the budding poet encountered no trouble mailing out his poetry in an attempt to get published. The authorities did not resist, he recalled, because they considered James Whitcomb Riley to be a poet and “they didn’t understand what I was all about.”

His first published piece, a tribute to Dinah Washington, appeared in the Negro Digest about a year after he started writing from prison. Once published, prison officials began censoring his mail and prohibited him from mailing out his poetry. Knight responded by “smuggling material out to friends . . . who worked on the outside.” This resistance to prison life manifested not only in words, but in behavior and he spent time in solitary confinement, or, as he termed it the “hole” and “on the rock.”

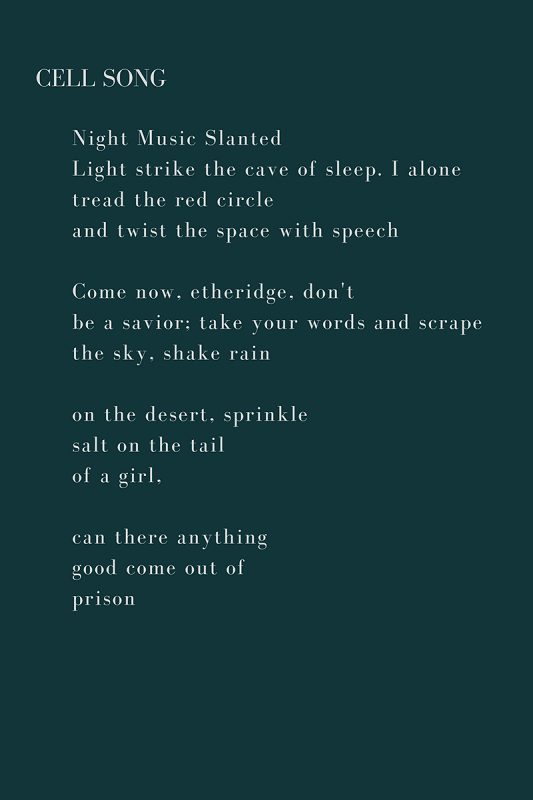

“The more oppressive the system you live under, the louder the poets scream,” Knight contended in 1989. And scream he did. His short stories and verses written in the penitentiary, were published in periodicals, anthologies, and the Journal of Black Poetry. Most famously, he published his book Poems from Prison, which included poems like “Cell Song” and “A Wasp Woman Visits a Black Junkie in Prison.” When he left prison in 1968 he worked as a punch press operator at a factory in Indianapolis. By 1972 his scream had been heard across the country and he had taught students creative writing at the University of Hartford in Connecticut and the University of Pittsburgh, and served as poet-in-residence at Lincoln University in Springfield, MO. He alleged that year that “There is more creativity going on in college campuses and prisons than any other places in the country.”

Knight assessed his years in prison, “My time made me see that prisons don’t rehabilitate. If you come out with any degree of sanity at all, you’re lucky. Prison is inhuman. It kills you.”

But poetry brought him back to life. Knight went on to establish Free People’s Poetry Workshops to counteract the “domination of the publishing industry by moneyed white males.” His books and spoken word garnered popular and critical acclaim and he received a fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation, won the American Book Award, and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

The poet, described by modern African American poet Terrence Hayes, as a “talented, ex-con, con man, blues-blooded rambling romantic” died in 1991 and is buried in Crown Hill Cemetery. For an in-depth examination of Knight’s works, see thepoetryfoundation.org.

Material for this post was derived from:

“Poet Gains Worldwide Acclaim,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 27, 1968, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

Helen Fogel, Detroit Free Press, February 22, 1969, accessed Newspapers.com.

Randi M. Pollack, “Etheridge Knight Talks on Prison,” The Baltimore Sun, February 18, 1972, accessed Newspapers.com.

Mike Fitzgerald, Palladium-Item (Richmond, Indiana), March 18, 1984, accessed Newspapers.com.

“Etheridge Knight: Going Against Safe Literary Doctrine,” The Indianapolis Star, March 12, 1989, accessed Newspapers.com.