Today, we drive over rivers and creeks in a few seconds and barely know their names. But before modern transportation severed so much of our connection to waterways, human contact with rivers practically defined life in water-rich Indiana.

One lost industry that had a brief “boom and bust” over most of the eastern U.S. a century ago was closely tied to the life of the rivers. If you’re keeping a list of industries (like steel and auto manufacturing) that have declined and even vanished from the Midwest, add one more: pearl button making.

Consumers today rarely give a thought to where buttons come from. How synthetic goods are made (i.e., the zippers, plastic buttons, and Velcro that partly replaced shell around 1950) may seem less “romantic” than the work of pearl fishermen hauling shiny treasures out of Midwestern streams in johnboats. Yet in spite of its nostalgic appeal, the pearl button industry also wreaked havoc on the environment and on workers in factories.

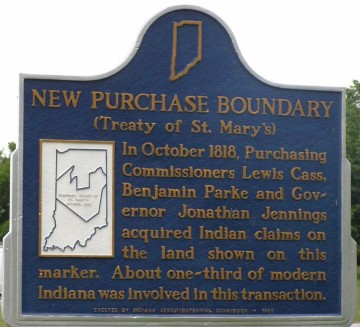

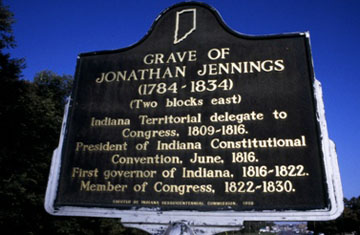

At the time of European settlement, midwestern rivers abounded in mussels. As many as 400 species probably lived in the Ohio Valley in 1800. The Mound Builder cultures that once occupied the American heartland found many ways to use mussels and left behind enormous refuse piles — what archaeologists call “middens” — in their towns, which almost always sat beside creeks and rivers. They were large towns, too. In the year 1200, Cahokia, across the Mississippi River from the future site of St. Louis, was bigger than medieval London.

Among Indiana’s early settlers, “diving” for pearls hidden in freshwater mussels dates back to at least 1846, when farmers at Winamac founded a small stockholders association to try to market shells taken from the Tippecanoe River. They sent a man to St. Louis and Cincinnati to ask about the value of freshwater pearls. Prices were low at the time and the “Pulaski County Pearl Diver Association” went bust.

Though a few button factories existed in Indiana before the Civil War — relying on shell, horn, and bone — the American freshwater pearl boom didn’t really gain momentum until 1900. In that year, a pearl frenzy erupted along the Black and White Rivers near Newport, Arkansas. Arkansas’ pearl boom had all the hallmarks of an old-time gold rush. A writer for the Indianapolis Journal reported in 1903:

Within the past three years more than $3,000,000 worth of pearls have been taken from the Mississippi Valley. . . The excitement spread from the land to the river steamboats. Their crews deserted them, and sometimes their captains, and the Black River was the scene of the wildest excitement. New towns were built and old ones were increased to the size of cities. Streets were laid out, banks and mercantile establishments were started, mortgages were lifted, money was plenty and times were prosperous. . . New York pearl dealers flocked there in great numbers.

The writer tells a story, perhaps exaggerated like much of his account, that an African American family who had lived in poverty made enough money pearling to build a large house and hire white servants. He also mentions that New York dealers were often ripped off by sellers masquerading Arkansas pearls as Asian.

Arkansas’ rivers were quickly “pearled out,” but the pearl boom spread and reached its peak around 1905-1910. Southwestern Indiana is almost as close to Arkansas as it is to Cincinnati. When the Southern boom died down, the hunt for pearls came north. The Jasper Weekly Courier reported in October 1903 that pearls had been found in the Wabash River at Maunie, Illinois, just south of New Harmony. “The river is a veritable bee hive and scores are at work securing mussel shells. The price of shells has risen from $4 to $15 a ton and an experienced man can secure a ton in a day. Farmers find it difficult to get farm hands.”

“Musselers” found an estimated $7000 worth of pearls in the Wabash in the first week of June 1909. Charles Williams, a “poor musseler,” found a “perfect specimen of the lustrous black pearl and has sold it for $1250. Black pearls are seldom found in freshwater shells.”

Vincennes experienced an explosion of musseling in 1905, as pearl hunters converged on the Wabash River’s shell banks. Eastern buyers came out to Indiana and frequently offered $500-$1000 for a pearl, which they polished into jewelry in cities like New York. A thousand dollars was a lot amount of money at a time when factory workers typically made about $8.00 a week. But with several hundred people eagerly scouring the riverbanks, the best pearls were quickly snatched up. For about a decade afterwards, “mussel men” and their families focused on providing shells for button manufacturers.

Interestingly, the shell craze caused a squatters’ village to spring up in Vincennes. A shanty town called Pearl City, made up of shacks and houseboats, sat along the river from 1907 to 1936, when as part of a WPA deal, its residents were resettled in Sunset Court, Vincennes’ first public housing.

At Logansport on the Wabash, patients from the Northern Indiana Insane Hospital spent part of the summer of 1908 hunting for pearl-bearing mussels. “One old man has been lucky, finding several pearls valued at $200 each. Local jewelers have tried to buy them but the old man hoards them like a miser does his gold. He keeps them in a bottle, and his chief delight is to hold the bottle so that he can see his prizes as the sun strikes the gems.” In and around Indianapolis, hunters discovered pearls in Fall Creek and the White River, especially around Waverly, southwest of the city.

Though every fisherman sought to find a high-value pearl and make a tiny fortune, the boom’s more prosaic side — button-making — eventually won out. From the 1890s to the 1940s, hundreds of small factories across the Midwest turned out glossy “mother-of-pearl” buttons. The industry especially flourished along a stretch of the Mississippi near Muscatine, Iowa, called the “button capital of the world.” Muscatine’s button industry was founded by John Boepple, a master craftsman from Hamburg, Germany, who immigrated to Iowa around 1887. Muscatine’s factories turned out a staggering 1.5 billion buttons in 1905 alone. About 10,000 workers were employed by button factories in the Midwestern states.

John Boepple lived to see the industry’s impact on rivers like the Mississippi. In 1910, the industrialist turned conservationist began work at a biological station established by Congress at Fairport, Iowa, to help repopulate mussels by reseeding riverbeds. Congress’ role was simply to preserve the industry, not to save decimated species. In 1912, the embattled mussels had their revenge: Boepple cut his foot on a shell and died of a resulting infection.

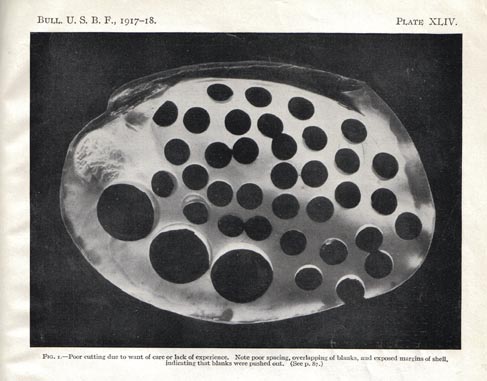

Although Iowa dominated the American button industry, numerous tiny factories popped up in small Indiana towns, including Mishawaka, Lawrenceburg, Leavenworth, Madison, and Shoals. (Shoals was named for its founder, Frederick Shulz, not for the mussel shoals on the White River.) Taylor Z. Richey, writing from Cannelton, Indiana, described how the work was done along the Ohio River in 1904. Many factories did not create the actual buttons, merely the “blanks” that were shipped out to Iowa.

Working in the button industry was far from quaint and actually proved a hazardous job. Exposure to hydrochloric acid and poor ventilation took a big toll on workers. Author Jeffrey Copeland notes that. there were more cases of pneumonia, typhus and gangrene among button factory laborers than in any other industry. Children as young as eight worked sixty-hour weeks carrying buckets of shells and acid to soften the material up. Eye injuries and loss of fingers often occurred as workers “stamped” the buttons out of shells or operated lathes. Even before the industry reached its turn-of-the-century heyday, gory accidents (such as this one, reported in the Jasper Weekly Courier in 1874) made it into the newspapers:

A French girl, sixteen years old, was caught by her long hair in a revolving shaft at a button factory in Kankakee, Ill., the other day, and the left side of her head was completely scalped. A severe concussion of the brain was also sustained. Her condition was considered critical.

Complaints about filth and dust drove Mishawaka’s factory to relocate to St. Joseph, Michigan, in 1917.

Partly under the leadership of a young activist named Pearl McGill, labor unions in Iowa battled it out with factory owners, culminating in Muscatine’s “Button War” of 1911, a fight that involved arson and the killing of police. In Vincennes in 1903, however, the usual pattern of Progressive-era labor politics seemed to go the other way around. The Indianapolis Journal reported that Eugene Aubrey, owner of a pearl-button factory at Vincennes and allegedly a member of the Socialist Party, fired worker Charles Higginbottom for serving in the militia during Evansville’s bloody July 1903 race riot, when many African Americans were gunned down. The Journal went on to accuse Aubrey of being a secret anarchist.

In his semi-fictional Tales of Leavenworth, Rush Warren Carter described a small-town Indiana button factory in those years. A boy named Palmer Dotson quits school at 16 and gets a job working under superintendent “Badeye” Williams. (Factory workers often lost eyes.) “Cutting buttons was not a business that developed one’s mind or elevated his thoughts,” Carter wrote. “The cutting process was a dull routine to a background of everything but enlightened conversation. Talk about your ladies’ sewing circles. When it came to gossip, [women] were not in the same league with the men in the button factory, who chewed and rechewed every real or imagined bit of gossip until it had been ground to a fine pulp.” Dotson died of tuberculosis at 21. A co-worker decided that opening a saloon would be preferable to stamping buttons.

In 1917, a silent movie based on Virginia Brooks‘ popular novel “Little Lost Sister” was playing at The Auditorium in South Bend. The plot begins in a sordid rural button factory in “Millville” (probably in Iowa), where the heroine, Elsie Welcome, has big dreams about getting out and going to Chicago. A classic stand-off with the foreman ensues:

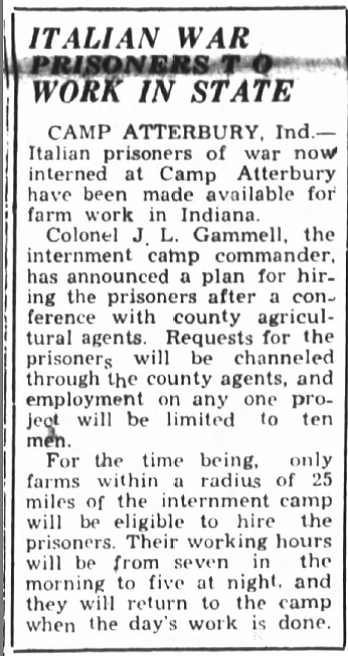

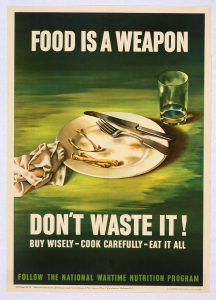

Although Iowa’s factories were still running in 1946 (the year actor Ronald Reagan chose Muscatine’s Pearl Queen), exhaustion of shell banks all over the Midwest was killing the industry fast. Japanese innovations increased competition after World War II. Synthetic plastics — which were cheap and could withstand washing machines better than shell — were pioneered in the 1920s and eventually took over the industry in the mid-1950s. Instead of smelly buckets of shells, workers handled tubs of polyester syrup. Then, two snazzy new inventions, zippers and Velcro, even cut into the demand for buttons outright.

Indiana’s factories, which had been shipping blanks to Iowa for years, had all gone out of business by the end of World War II. The last independent buttonworks in the U.S., the Wilbur E. Boyd Factory at Meredosia on the Illinois River, closed in 1948. Iowa’s button industry hung on until the mid-1990s, when Chinese innovations in pearl cultivation finally caused it to collapse.

Contact: staylor336 [AT] gmail.com