A farmer woke up on a cool fall day in the 1820s, not long after Indiana became a state, with a lot on his mind. He worried that he might not get all of the crops in before the first frost and that his hogs wouldn’t fetch as high a price at the market this year. His wife worried about whisperings in town that the milk sickness had claimed another neighbor. Their children didn’t have much time to worry though. They were up before the sun to feed the animals and clear the wild back acres. Whatever their specific trials, they had more immediate concerns than learning algebra, astronomy, philosophy, or the history of ancient Greece.

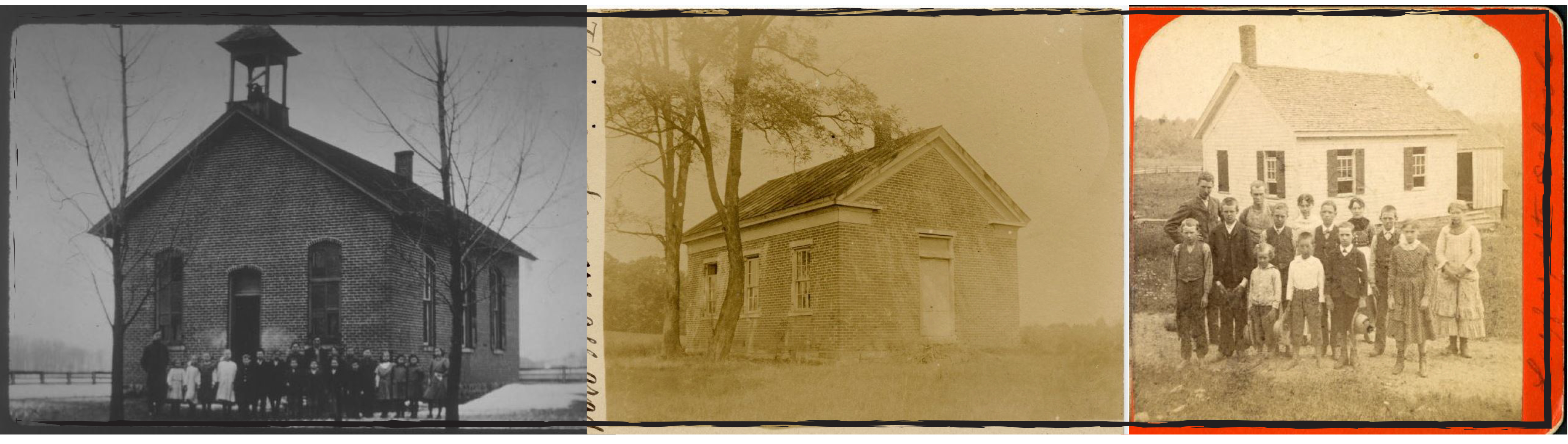

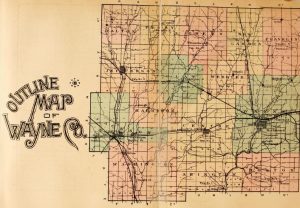

For many Hoosiers, education was not a priority compared to the immediate needs of the family farm or business. But others craved knowledge beyond the basic reading and arithmetic taught in one-room school houses. These ambitious students desired knowledge of the wider world, and fortunately for them, the State of Indiana worked to provide institutions of learning to meet their aspirations. In the case of the Wayne County Seminary, in the small but thriving town of Centreville (later Centerville), the mission was an incredible success. Over several decades hundreds of young men and women pursued advanced education within its walls.

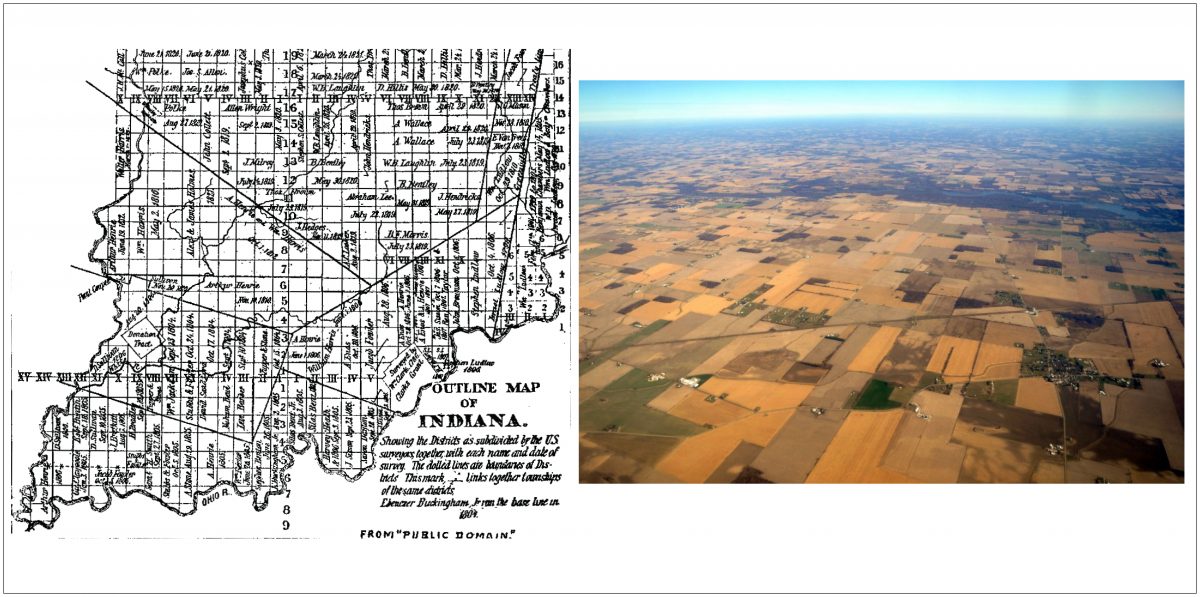

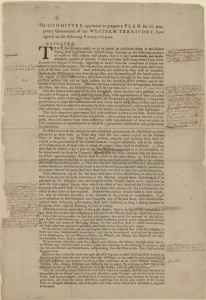

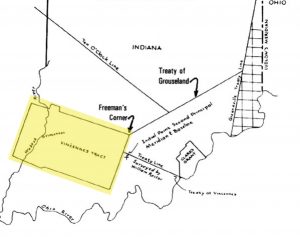

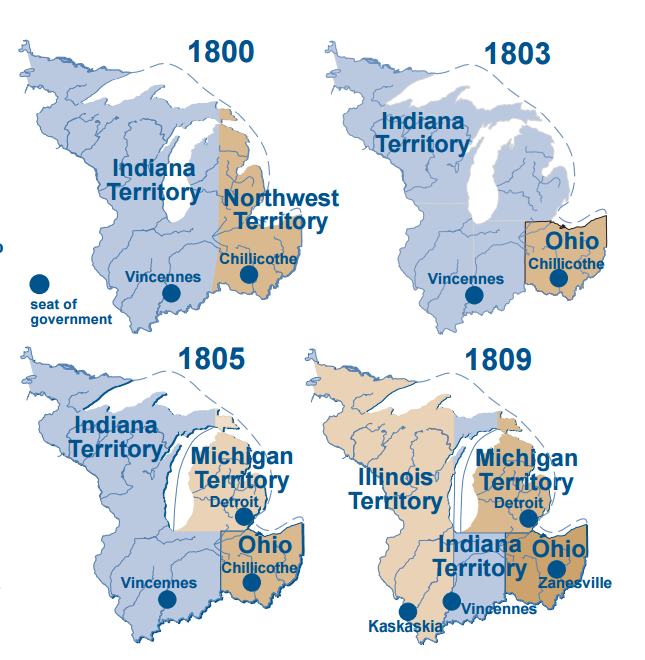

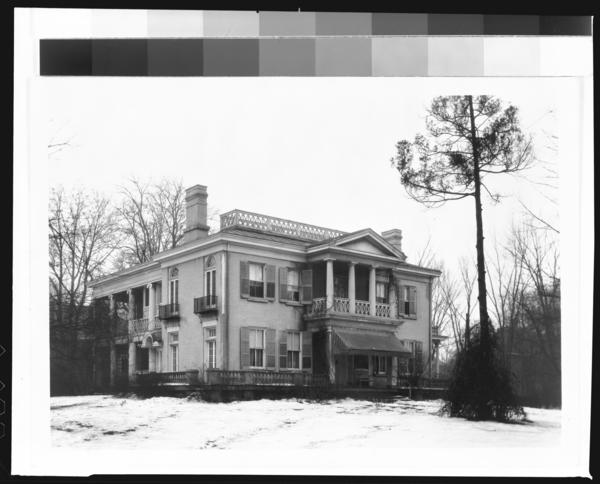

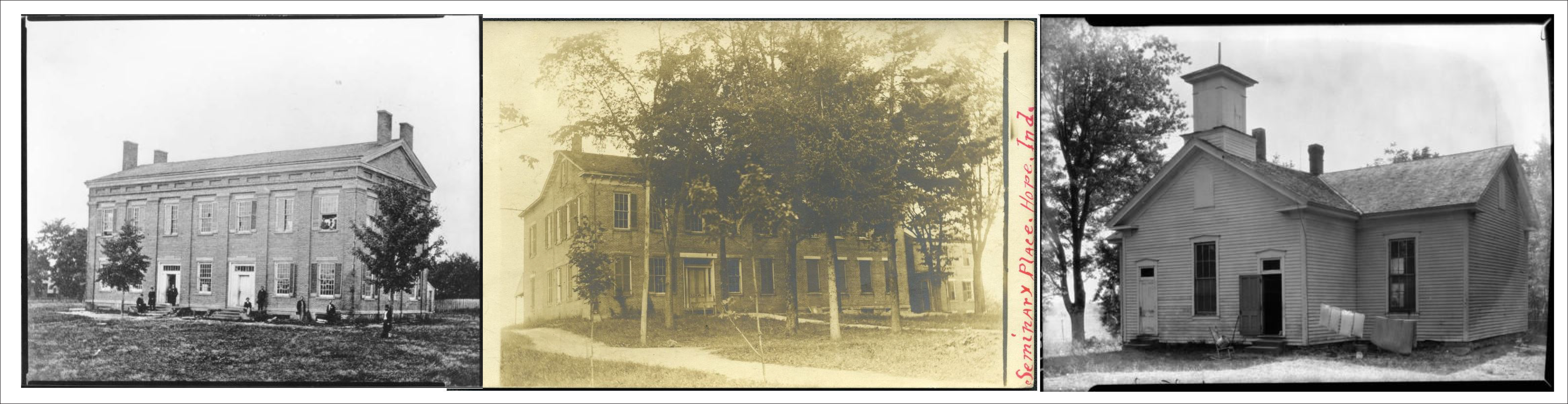

The 1816 Indiana Constitution and subsequent acts of the Indiana General Assembly encouraged and provided for the creation of an educational center in each county open to all citizens (although not free of tuition) known as a “county seminary.” By the late 1820s, many Indiana counties had established such an institution. While today “seminary” refers to a theological school preparing students for ministry, the county seminaries were non-denominational. They included primary and secondary classes and in some cases even collegiate and classical courses of study. In counties where the township schools flourished, the seminaries offered only the higher education classes . In January 1827, the Indiana General Assembly passed an act requiring the appointment of “County Seminary Trustees,” who were charged with acquiring land and contracting a building. Wayne County appointed its trustees in June 1827. Over the following year and a half, the trustees secured a location and built a fine brick structure that would house eager students for over sixty years.

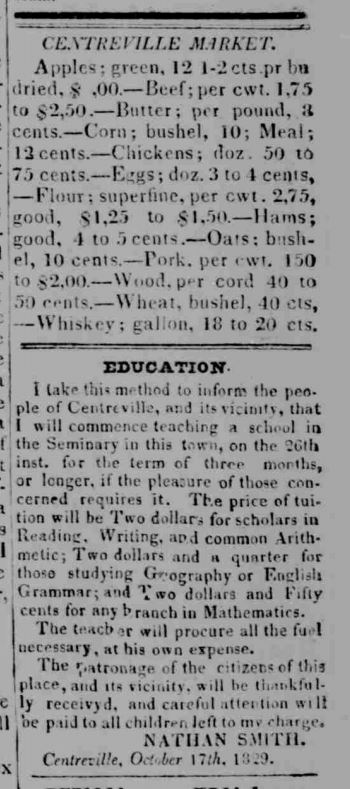

The Wayne County Seminary opened humbly. Teacher and administrator Nathan Smith announced via local newspapers that he would, “commence teaching a school in the Seminary in this town” on October 26, 1829, for a term of “three months, or longer, if the pleasure of those concerned requires it.” Tuition during this first term ran parents two dollars if their young scholar studied geography and English grammar and two dollars and fifty cents if mathematics was included. At the time, this was a good amount of money. For comparison sake, on the same page of the Western Times that the seminary announcement appeared, the Centreville Market advertised a dozen eggs for three to four cents and “Hams, good” for four to five cents, while whiskey would have cost you a whopping eighteen to twenty cents for a gallon. So, in 1829, fifty good hams could get you into Wayne County Seminary. This calculation is more than an exercise. Over the following years, the school would allow the mainly agrarian locals to trade produce and farm products for education.

By 1835, the school blossomed into a more advanced academy, though several newspaper articles imply this did not happen with ease. The greatest challenge was likely promoting the need for higher education to the residents of the surrounding regions. In a public announcement, the Wayne County Seminary Trustees stated: “An academy in which the higher branches are taught has long been wanted in our county, and we should be pleased to see the present attempt to establish one, patronized.” By this point, the school was attracting some students “residing distant from Centreville” and the trustees noted that boarding could be found in town for “as cheap as in any other town in the west.”

By this point, the school was “under the superintendence” of Giles C. Smith. The new superintendent had a stronger educational background than the average Indiana teacher at this time, evidenced by the fact that he went on to become a respected Methodist minister and leader within the Methodist Episcopal conference. In fact, for much of the school’s history, notable Methodist leaders made up the board and administration. The school, however, remained non-denominational, with no religious classes and with boarders attending the Sunday church service chosen by their parents. The trustees described the growing institution as “commodious and pleasantly situated,” and noted that the seminary trustees, if they did say so themselves, were “gentleman of liberality and integrity.”

This “liberality and integrity” was not simply promotional. It extended into the trustees’ educational philosophy as evidenced by one important element of the school: Wayne County Seminary provided young women the same educational opportunities as the young men. In 1835, the trustees made their case to local parents in the Richmond Palladium:

Considering, that the reputation and utility of the Seminary stand closely allied with the literary interests of this county, and knowing that the location of the one is nearly equidistant to the boundaries of the other, [the trustees] do earnestly invite those gentlemen, who know and appreciate the worth of a good education in the youth of the country, to place their sons, daughters and wards within this institution.

From the casual tone of appeal to parents to send their daughters, it seems likely that women had been included for some time, if not from the start. This 1835 trustees’ statement is no declaration that the school recently started accepting young women. Instead, it assumes some sort of general knowledge that young women had already been attending the school and expresses their hope that more young women would enroll.

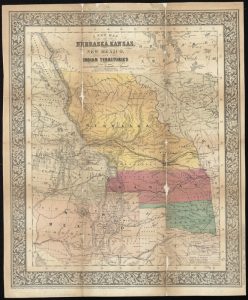

Also from this 1835 announcement, we’re offered a look at the elementary and higher education curriculum. The elementary students could study reading, penmanship, orthography (spelling), and arithmetic. The secondary classes included English grammar, history, bookkeeping, geography, “and the use of the Globes.” Finally, the higher education classes included algebra, geometry, surveying, astronomy, Greek and Latin, and “Natural and Moral Philosophy.”

The trustees also announced in 1835 that superintendent Smith would “be aided in his labors by the additional services of Mr. S. K. Hoshour.” By the following year, Samuel K. Hoshour took charge of the seminary and became perhaps the school’s most influential administrator. During Hoshour’s time at the Wayne County Seminary, he mentored several students who went on to become important Hoosiers, including Jacob Julian, Oliver P. Morton, and Lew Wallace. It’s worth stepping away from the seminary story to look briefly at the careers of these Wayne County luminaries.

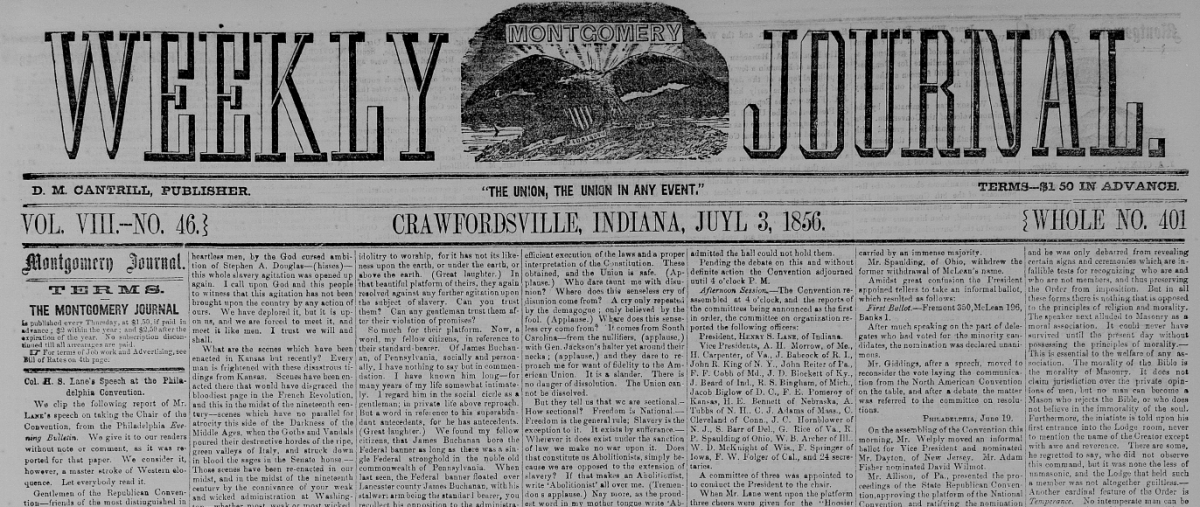

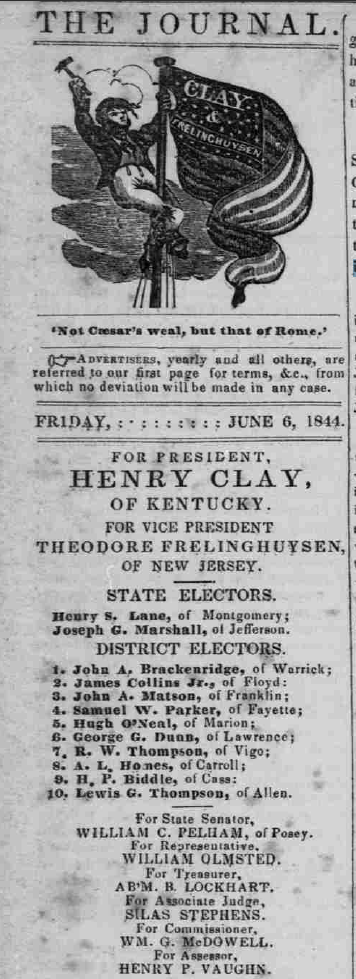

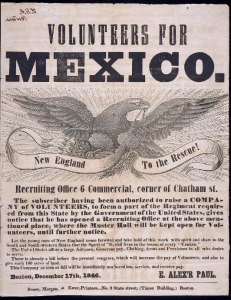

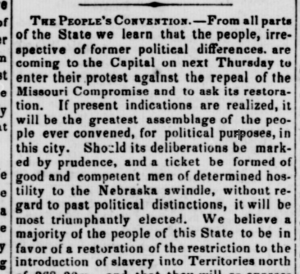

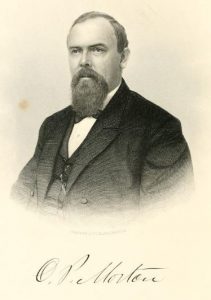

Oliver P. Morton also began his career as a lawyer in Centreville. He represented Wayne County at the seminal first convention of the new national Republican Party in 1856. He was elected lieutenant governor of Indiana in 1860, but almost immediately became governor when Henry S. Lane left the position for a U.S. Senate seat. Morton served as governor throughout the Civil War and won election to a second term in 1864. He completed Lane’s term in the U.S. Senate in 1867 and was reelected again in 1873.

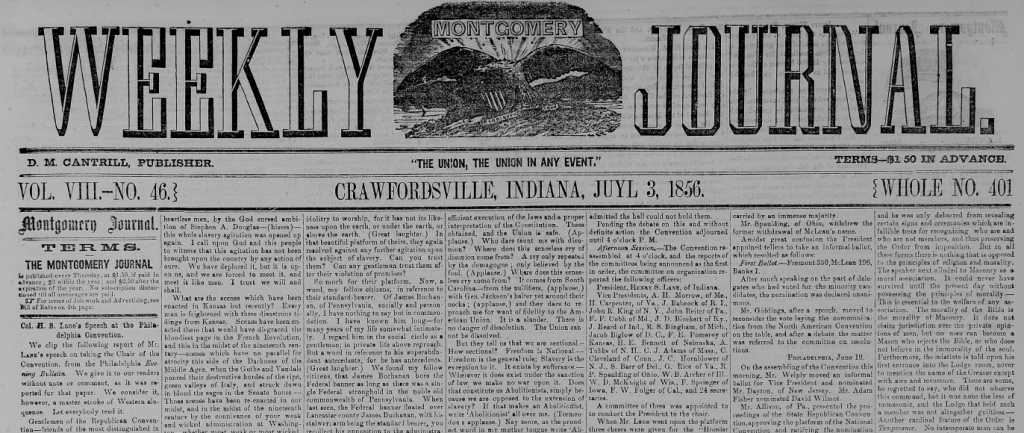

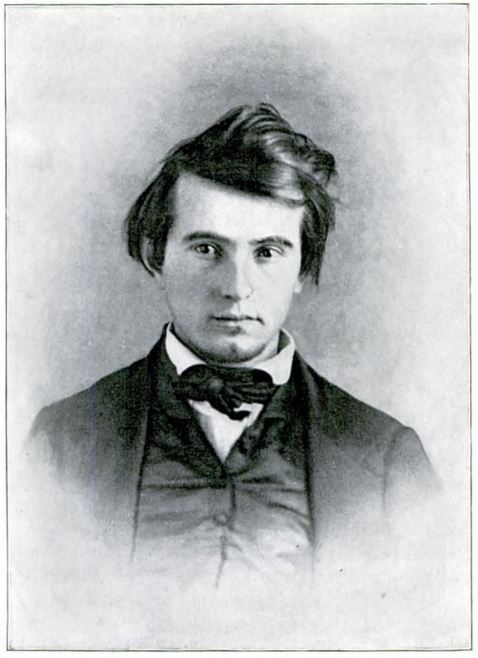

Lew Wallace, the son of an Indiana governor and grandson of a congressman, began a law practice in 1849, and settled in Crawfordsville in 1853. With the start of the Civil War in 1861, he volunteered for service and before the war’s end was a major general. Wallace later served as governor of the New Mexico Territory and U.S. minister to Turkey (the Ottoman Empire). He is best remembered and acclaimed as the author of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880).

Later in life, Wallace expressed how important his time at the Wayne County Seminary was to his creation of his famous novel. In his autobiography, Wallace described the profound influence that Professor Hoshour had on his writing. Wallace remembered attending the seminary in his “thirteenth year” because “there was a teacher of such repute that my father decided to send me to him.” Wallace wrote:

Professor Hoshour was the first to observe a glimmer of writing capacity in me. An indifferent teacher would have allowed the discovery to pass without account; but he set about making the most of it, and in his method there was so much wisdom that it were wrong not to give it with particularity… The general principle on which the professor acted is plan to me now. The lack of aptitude for mathematics in my case was too decided not to be apparent to him; instead of beating me for it, he humanely applied to cultivating a faculty he thought within my powers and to my taste.

Hoshour gave Wallace great works of literature and advice on writing. Wallace remembered Hoshour explaining the most important rule of writing: “In writing, everything is to be sacrificed for clearness of expression – everything.” Finally, Hoshour encouraged Wallace to read the Bible through a literary lens as opposed to a dogmatic focus. Wallace recalled:

This was entirely new to me, and I recall the impression made by the small part given to the three wise men. Little did I dream then what those few verses were to bring me – that out of them Ben-Hur was one day to be evoked.

Wallace referred to his time with Hoshour as “the turning-point of my life.”

While the seminary forged some great Hoosier men, the young women of the Wayne County Seminary thrived as well. Although the prejudices and legal obstacles of the period kept them from the public successes of their male peers, sources show the female students equaled the male students’ academic achievement, and perhaps even exceeded them in some areas. The young women took classes on the same subjects as the young men, but their classes were separate and taught by female teachers.

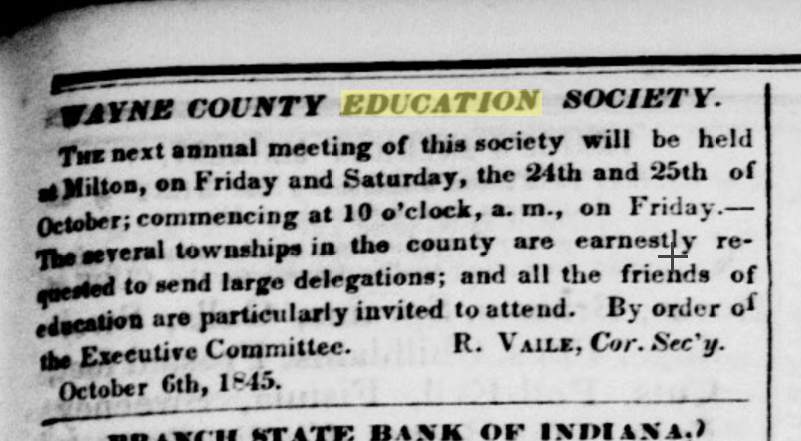

Several sources show that these women were highly respected in their community, praised by newspaper writers, and in in many ways treated as peers by their male colleagues. For example, when the county’s teachers formed the Wayne County Education Society in the early 1840s, seminary teachers Mary Thorpe and Sarah Dickson were not only included, they served on various committees that decided appropriate school texts, punishments, and funding. They served side by side with their male colleagues and prominent community members such as Levi Coffin, George Washington Julian, and Solomon Meredith.

Female teachers also served as the administrators of the girls’ school, which maintained a surprising degree of autonomy. Evidence of this autonomy can be gleaned from Wayne County newspapers. For example, in February 1842, the Richmond Palladium reported that a new principal, Rawson Vaile, had replaced the former seminary administrator, George Rea. The following month, Rea placed an announcement in the Wayne County Record somewhat dramatically decrying his removal and announcing his plan to open a rival school. Through this unrest at the seminary, teacher and administrator Mary Thorpe, calmly steered the girls’ school through the storm. She ran her own advertisement in the Wayne County Record, assuring her students:

Miss Thorpe Respectfully informs the Citizens of Centreville, that the late change in the Wayne County Seminary, will in no way affect her School; but that it will, as heretofore, remain under her exclusive control.

Throughout the 1840s, the Wayne County Record covered the “public examinations” of both the male and female students. During these student exhibitions, parents and other Wayne County residents packed into the nearby Methodist church as it was the only building large enough to hold the interested crowds. The program featured original essays, debates, as well as musical and dramatic performances. In March 1842, the Wayne County Record covered the examination of the male students and praised Principal Vaile, focusing on his penchant for strict discipline. However, the newspaper was harshly critical of the enunciation and articulation of the male students.

In contrast, a month later on April 13, the same newspaper raved about the “Female Department of the Wayne County Seminary” and called their public exhibition “one of the best examinations we have ever attended in this place.” The writer noted that the students did not just repeat rote, memorized facts, but had a deep understanding of their subject matter. The article stated:

From the lowest classes, studying the simple elements of Geography, or numbers, up to those in the higher branches of Natural Philosophy, Grammar, Astronomy, Algebra and Political Geography, all, as far as they had severally* advanced, seemed to understand the ground over which they had traveled. They did not possess a mere smattering knowledge but could readily tell the why and wherefore of the question propounded to them.

The Wayne County Record also praised Sarah Dickinson, the able teacher of these impressive young women: “We feel assured that no one has ever taught here, either Male or Female, that has given more general satisfaction.” Let’s hazard a guess that the young women would have been quite pleased with their success, and maybe even by their besting of the young men in the press’s estimation.

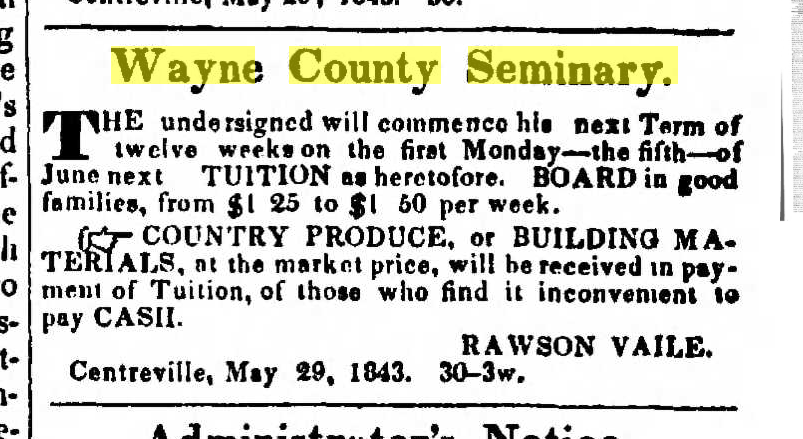

The Wayne County Seminary continued to flourish and grow in both enrollment and size. By 1843, the school expanded classroom space and lodging and the addition of more upper level classes in languages and sciences. The women could also now pursue a music focused curriculum if desired. The article noted that the seminary included “Three several Schools,* one Male and two Female,” and reiterated that “Pupils, in either the Male or Female departments” could pursue “the ordinary branches of an English Education” or the higher level courses of “Astronomy, Botany, Natural Philosophy, Mathematics, Geology, and the Latin and French Languages.”

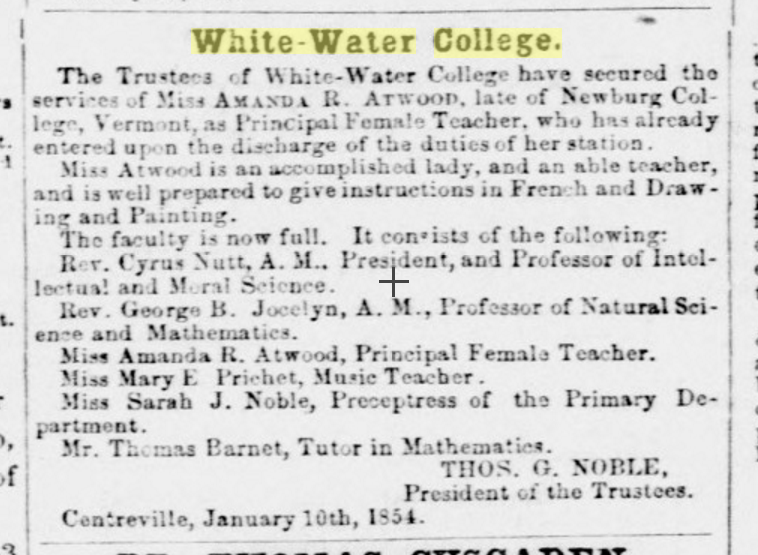

By the late 1840s, the institution reorganized and the new board of trustees changed its name to Whitewater Female College and Academy. Despite this somewhat misleading name, the school continued to educate both young men and women. While the board was now under the administration of the Methodist Episcopal Northern Indiana conference, classes remained secular and boarding students could still attend the church of their parents’ choice on Sundays. Notably, in 1849, the female students founded the prestigious Sigournian Society, a literary organization with its own library at the school. The society held exhibitions of original essays, hosted lively political debates, and performed music. The crest of the society featured an open book with a halo of light with their motto: “Many shall run to and fro and knowledge shall be increased” (Daniel 12:4).

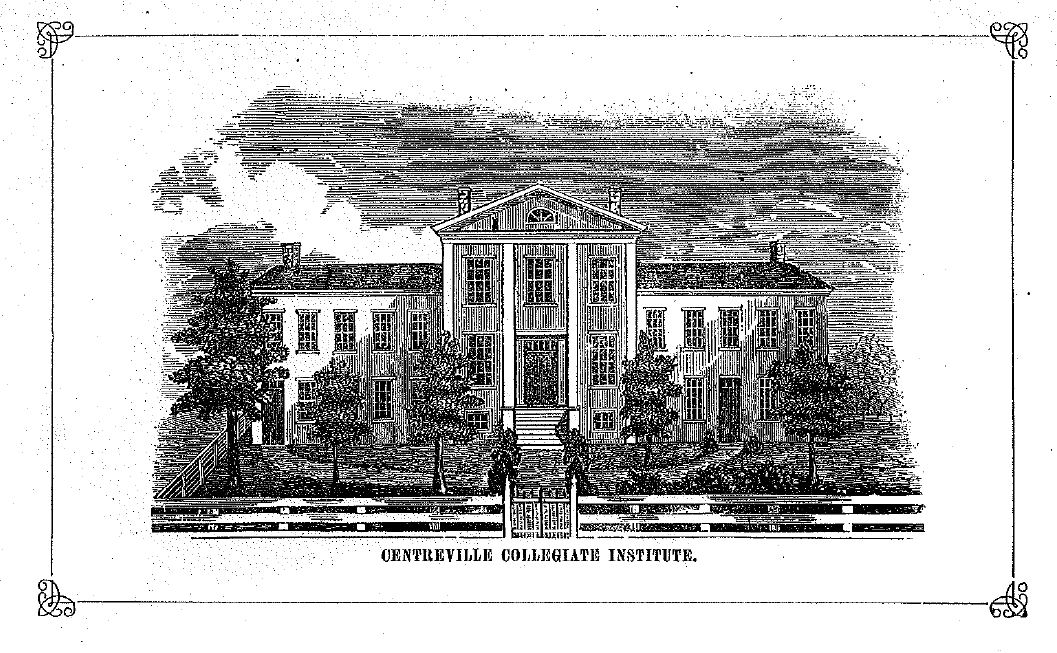

Over the following decades the school saw many changes but ardently continued its lofty educational mission. By the 1850s, the school, still under the “patronage” of the Methodist Conference, became known simply as “White Water College.” By this point, over 200 students attended the institution. In the early 1860s, after some financial trouble, the board sold the institution to Wiliam H. Barnes who remodeled and reopened the school and served as its president for a time. In 1865, the academy again changed administration and name, reopening in September 1865 as the Centerville Collegiate Institute. In the early 1870s, the site that once hosted the prestigious Wayne County Seminary became a public school. All signs of the original school were destroyed by fire in 1891.

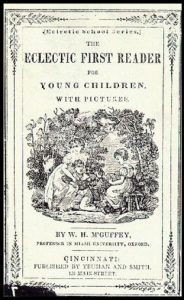

Today, not far from the site of the seminary, local kids attend Centerville Elementary School. If the teachers were to have their kids look out of the school’s east facing windows, perhaps they can imagine their distant relatives walking into the old seminary carrying “McGuffey’s Eclectic Series of School Books” and maybe even “country produce or building materials . . . in payment of Tuition.” And the teachers can appreciate that, while they might still have the same problems that Professor Vaile had in 1842 in getting his students to enunciate clearly, at least they don’t have to “procure all the fuel necessary” this icy winter as Professor Smith did back in 1829 at the opening of the ambitious, progressive, and democratic Wayne County Seminary.

Sources and Research Note:

Most of the primary sources referenced in this are newspaper articles accessed via Hoosier State Chronicles. A complete list of all articles used can be downloaded here: Wayne County Seminary timeline.

Most secondary information came from: Richard G. Boone, A History of Education in Indiana (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1892), 42-86.

*I came across scattered mentions of the term “several schools” in the contemporary newspapers. Though I was not able to find a precise definition, I gleaned from the context of the articles that the term refers to the level of education after primary and before college, roughly equivalent to what would be middle school through high school today.