The black snake undulated between the two women, winding back and forth, circling overhead. A lascivious leer seemed to be affixed to the snake’s mouth as it weaved, moving the women closer, but then winding between and pulling them apart. Augusta Knabe could not bear to see this horrible apparition between them. She reached for her cousin.

Augusta lost her grip on Helene and sat up in bed, struggling to catch her breath. She pushed her sweat-drenched hair back and collected herself. What a horrible dream! Augusta felt guilty she had not accepted her cousin’s offer of tea the past afternoon. She was sure the dream was her penance for wanting to avoid late afternoon traffic and enjoy the comfort of her home after shopping. Augusta promised herself she would stop by Helene’s flat after school and take her to tea the very next afternoon. Despite this promise, Augusta passed the rest of the night fitfully.

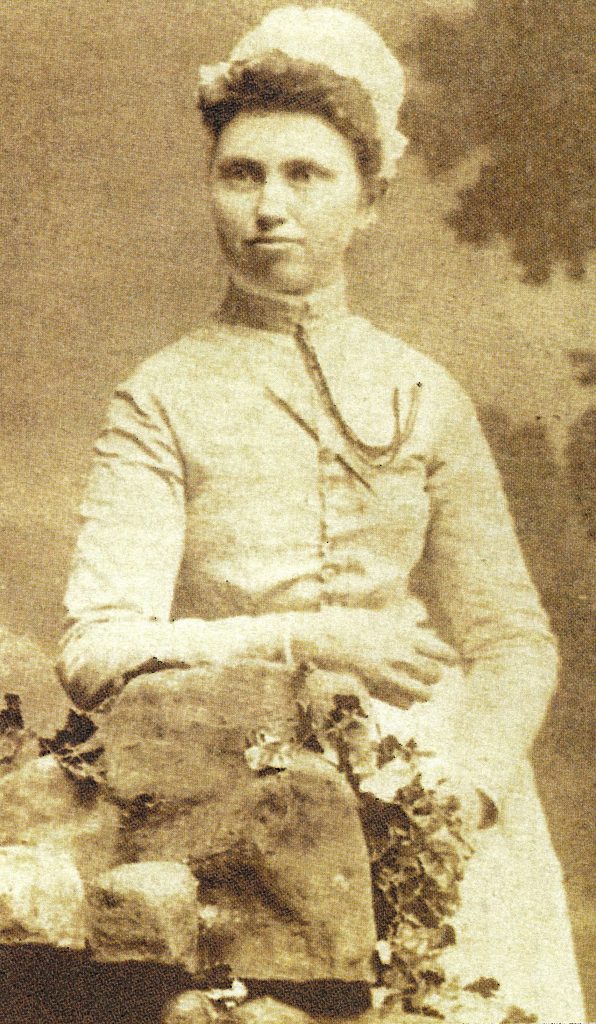

Augusta’s cousin, Helene Elise Hermine Knabe, yearned to be a doctor. In Germany women were not allowed in medical school until 1900 and it would not be allowed for women in the German state of Prussia, where she lived, until 1908. Her father, Otto Windschild, left her mother when Knabe was an infant and she was raised by her uncle after her mother died. Given her humble upbringing, becoming a doctor became more of a dream and less a reality with each passing year.

When Augusta informed Helene that women were allowed to attend medical school in America, Helene’s life changed forever and she moved to Indianapolis in 1896. The motto she heard most often growing up was “You cannot be a master in anything unless you know every detail of the work.” No one applied this maxim more than Knabe. To prepare for school she worked for four years in domestic and seamstress work in order to learn English from the upper class. She attended Butler University for a term to supplement her self-learning and to prepare her for the rigors of medical school.

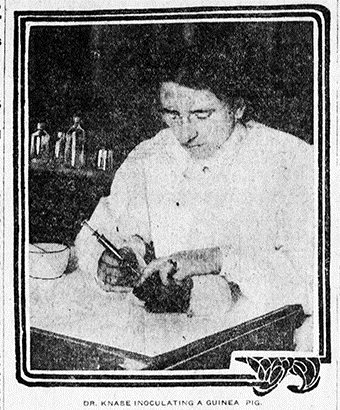

In 1900, Knabe entered the co-educational Medical College of Indiana (MCI). She was required to attend classes, dissect every body part of cadavers, maintain a 75% grade in all classes, refrain from drinking, and work fourteen hour days. During this time, she continued as a seamstress to supplement her income. Knabe also used her drawing skills by providing medical textbook illustrations to several books, including detailed sketches for anatomy, surgery, and pathology slides.

Knabe proved a trailblazer with her medical school accomplishments. Dr. Frank B. Wynn, the Director of Pathology at MCI, appointed her curator of the pathology museum. She was consequently placed in charge of the pathology labs at the school. Much to the chagrin of many of her male peers, Dr. Wynn chose her to be his only preceptee for the year. She began teaching underclassmen, an unheard of honor for a student. On April 22, 1904, Knabe became one of two women to graduate from MCI. She threw herself wholeheartedly into her profession, burning the candle at both ends to gain a foothold in practice, networking, and skills.

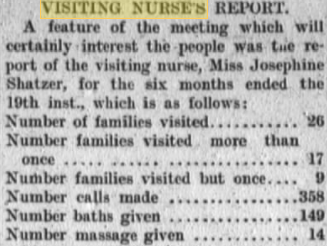

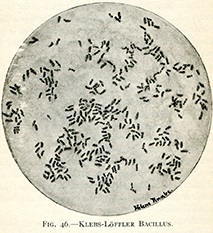

Dr. Knabe stayed on in her positions as lab curator and clinical professor—for which she was not paid. Appointed a deputy state health officer in 1905 by Dr. J. N. Hurty, the Secretary of the Indiana State Board of Health (ISBH), Dr. Knabe became the first woman to hold this office in Indiana. Part of her duties involved investigating suspected epidemics, such as typhoid and diphtheria, and making recommendations to reverse unsanitary conditions. Dr. Knabe routinely traveled the state to work with the public and doctors, and processed hundreds of pathological samples.

Despite Dr. Knabe’s expertise, Dr. Hurty did not hire her as superintendent of the lab. Instead, he chose Dr. T. V. Keene, regardless of the fact that he did not apply for the job. As the laboratory grew, Dr. Knabe became Assistant Bacteriologist and was expected to work longer hours and spend more time in the field. During her work at the ISBH, Dr. Knabe presented papers and worked with the public in diagnosis and education. Local papers interviewed her for her thoughts on how to make Indianapolis a more beautiful and clean city.

Dr. Knabe also kept current on new methods, most notably studying with Dr. Anna Wessel Williams of the New York Research Laboratory. Dr. Williams was brilliant in her own right as the originator of the rapid diagnosis of rabies, which was based on research from Negril and the co-developer of the diphtheria antitoxin. Dr. Knabe proved the widespread existence of rabies in Indiana. From this work, she implemented ways to prevent the spread of rabies by educating the public about the disease and its consequences.

Widely accepted as the state expert on rabies, Dr. Knabe was promoted to acting superintendent and paid $1,400 annually. Dr. Hurty promised her the superintendent position and an increase to $1,800 or $2,000. Over a year later Dr. Hurty told Dr. Knabe that there was no money for her salary increase and that because she was a woman she could not command the amount of money the position should pay anyway. Dr. Knabe contacted the newspaper and tendered her resignation, citing discrimination and broken promises.

Dr. Hurty had searched for what he considered “a real capable man” by actively recruiting Dr. Simmonds as the new superintendent. Additionally, although Dr. Hurty told Dr. Knabe the state had no money for her raise, he informed Dr. Simmonds he would pay $2,000 the first year and $3,000 in the second. That was a 47% increase from Dr. Knabe’s salary. The final slap in the face came from Dr. Simmonds himself in the first 1909 Indiana State Board of Health bulletin. He published Dr. Knabe’s findings about rabies in Indiana and elsewhere without crediting her.

Leaving the oppressiveness of state employ could not have been better for Dr. Knabe. Her dedication to medicine was rejuvenated. She opened her own private practice and continued her rabies research at $75 or more per case. While many female physicians shied away from accepting male patients because they may not be taken seriously or feared being attacked by male patients, Dr. Knabe insisted on having a phone installed in her apartment in case a patient needed her. She would always answer a knock or a call, regardless of the hour. Quite often she would treat people for free or accept payments via the barter system. This is how she acquired a piano and the lessons to go with it.

One of her biggest achievements was when she became the first elected female faculty for the Indiana Veterinary College (IVC), where she was the Chair of the Parasitology and Hematology. Dr. Knabe’s tenure at the IVC predates any recognized woman department chair at any veterinary college in the United States prior to 1920.

Demonstrating her willingness to be a social feminist, Dr. Knabe bucked trends at every turn by her work in sex education. She served as the medical director and Associate Professor of Physiology and Hygiene, known today as sex education, at the Normal College of the North American Gymnastics Union in Indianapolis. She also networked with women’s clubs and the Flanner House to create and teach hygiene and sanitation practices to all ethnic groups across the State of Indiana, especially African American communities.

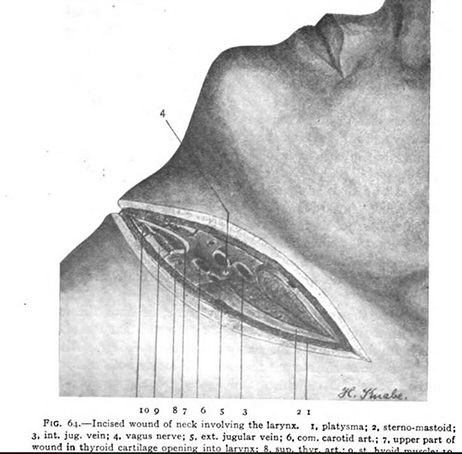

The same night that Augusta dreamt about the black snake, a person entered Dr. Knabe’s rooms at the Delaware Flats and brutally cut her throat from ear to ear. The killer was skilled enough to cut her on one side first, missing her carotid artery and cutting deep enough to cause her to choke on her blood. The second cut just nicked the carotid artery and cut into the spine. See Part II to learn how Dr. Knabe’s non-conformist lifestyle and work as a female physician would be used against her in the bungled pursuit of her killer.

* To learn more about the extraordinary life of Dr. Knabe, see She Sleeps Well: The Extraordinary Life and Murder of Dr. Helene Elise Hermine Knabe.