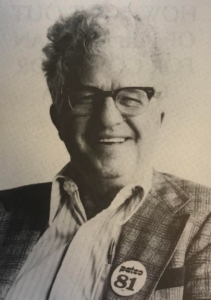

Physicist and educator Dr. Melba Phillips of Pike County, Indiana was an esteemed colleague of J. Robert Oppenheimer and important innovator in her own right. The two young scientists introduced a foundational physics principle, the Oppenheimer-Phillips Process, before taking separate paths. Phillips became an influential educator while Oppenheimer . . . well, I don’t want to spoil the movie for you. And while Phillips does not appear in the film, she did play an important role in the “heroic age” of physics, especially those exciting years that she and Oppenheimer spent at the University of California, Berkeley.

Melba Newell Phillips was born in 1907 in Pike County to a family of teachers. She graduated early from Union High School and enrolled at Oakland City College (now University) in Gibson County. There she benefitted from several important mentors, developed foundational math and science skills (though she recalled learning more physics from textbooks than her professor), and pushed back against conservative rules and instructors. This independence and refusal to compromise would serve her later in life. [1]

After graduating in 1926, Phillips taught briefly at Union High School before accepting a teaching fellowship at Battle Creek College in Michigan. She taught classes and filled in the gaps in her physics education by taking advanced courses. She earned her master’s degree in 1928 at the age of twenty one. In the summer of 1929 she attended a symposium on theoretical physics at the University of Michigan taught by Edward U. Condon, a distinguished and innovative physicist who would later join the Manhattan Project. Phillips impressed Condon and on his recommendation was accepted to the PhD program at the University of California Berkley in 1930. [2]

There was no better place for a young physicist in the 1930s than Berkeley. After World War I, the university devoted abundant resources to the physics department. They hired innovative scientists as teachers and built cutting-edge facilities to encourage experimentation. For example, the university hired renowned scientist Ernest Lawrence, who in 1931 invented the famous cyclotron, a particle accelerator that allowed the user to smash open atomic nuclei. Lawrence worked with his fellow faculty members Emilio Segre and Owen Chamberlain using both theoretical physics and the cyclotron to confirm the existence of the antiproton. All three received the Nobel Prize and joined the Manhattan Project.[3]

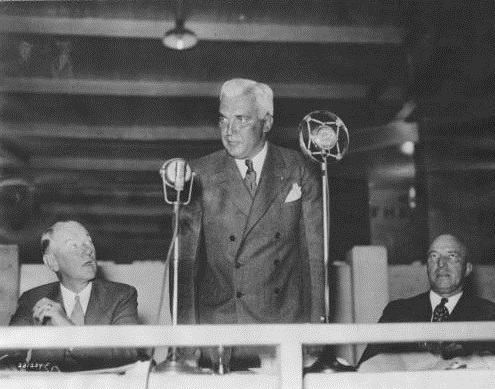

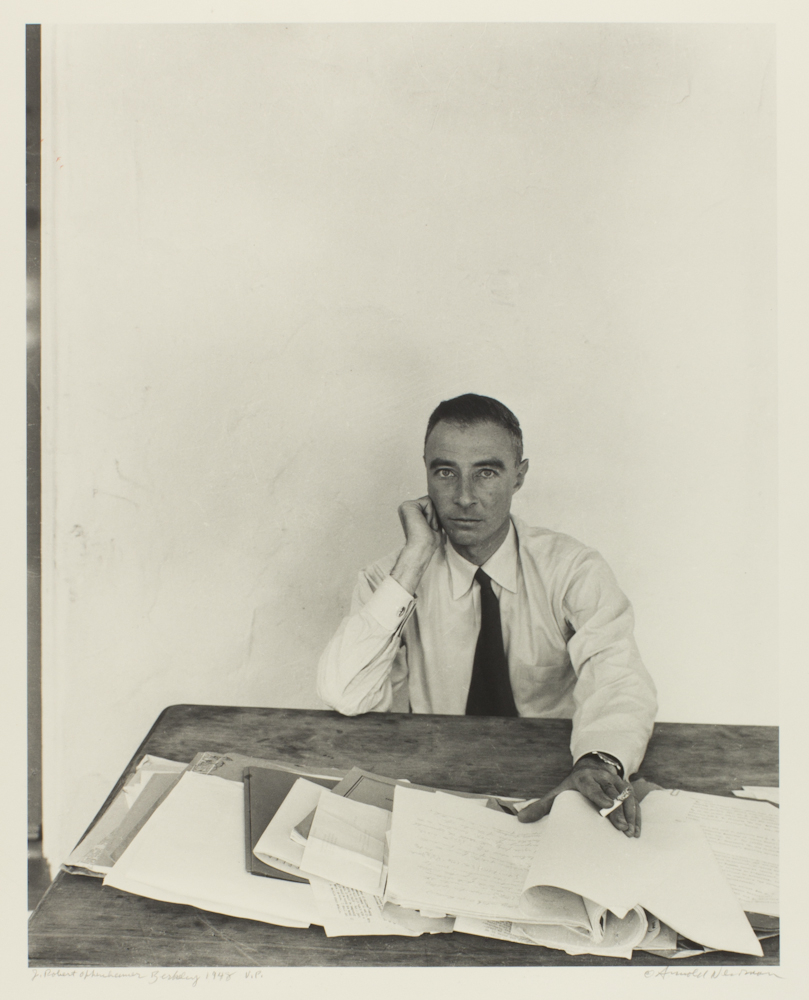

The faculty member who worked most closely with Phillips, greatly influenced her, and became a lifelong friend: the renowned J. Robert Oppenheimer. He had come to Berkeley as an assistant professor of physics in the summer of 1929, shortly before Phillips. He taught theoretical physics, an area in which Berkeley was weak. Oppenheimer explained that he didn’t teach students to prepare them for careers, but instead was motivated by including them in the unsolved problems of the physics world. He stated:

I didn’t start to make a school. I didn’t start to look for students. I started really as a propagator of the theory which I loved, about which I continued to learn more, and which was not well understood and which was very rich. The pattern was not that of someone who takes on a course and teaches students preparing for a variety of careers but of explaining first to faculty, staff, and colleagues and then to anyone who would listen, what this was about, what had been learned, what the unsolved problems were. [4]

Phillips was profoundly drawn to solving the unknown, something she had ruminated on as an undergrad. Oppenheimer was the perfect mentor for her curious nature and ambition.

By 1931, Phillips had chosen two topics within the field of experimental physics to study and work into her doctoral dissertation. (Experimental physics is the branch of the field dealing with observation of physical phenomenon through experimentation to test a theory. In turn, these experiments further shape new theories. They are symbiotic sub-disciplines.) As theoretical physics was Oppenheimer’s area of expertise, he became her advisor, and almost immediately, her friend. By 1933, she had worked both of her topics into a dissertation–each of which could had been a dissertation unto itself, according to her peers. [5] Physicists Dwight Neuenschwander and Sallie Watkins explained:

Melba was not the kind of physicist who enters a new field, picks all the low-hanging fruit, and moves on. Rather, the fruit that Melba harvested required her to climb high into some very tall trees. She solved difficult problems, and was a stickler for detail, to do the job right . . . Melba asked genuine questions in her papers. To answer them she invoked fundamental principles, then developed them with sophisticated calculations and insightful approximations and, quite often, with numerical integrations that had to be done by hand because programmable computers had not yet been invented.[6]

Even before her dissertation was finished, several academic journals published Phillips’s work. She had begun to make a name for herself in the physics world and had made herself the peer of her mentor. In 1933, Oppenheimer called her “an extraordinarily able woman” with “a genuine vocation for mathematics and theoretical physics, and an outstanding talent for it.” [7] He praised her “difficult and important” contributions to theoretical physics while studying at Berkeley and stated that he could “fully recommend her as a valuable member of any university physics department in the country,” although he would “regard it as a very real loss” t0 his department.[8] A full-time job remained elusive, in part because of the Great Depression, but gender discrimination undoubtedly contributed. After earning her Ph.D. in 1933, Dr. Phillips stayed nominally employed with a combination of work as a research assistant and a part-time instructor. She used her extra time at the university to advance her career.

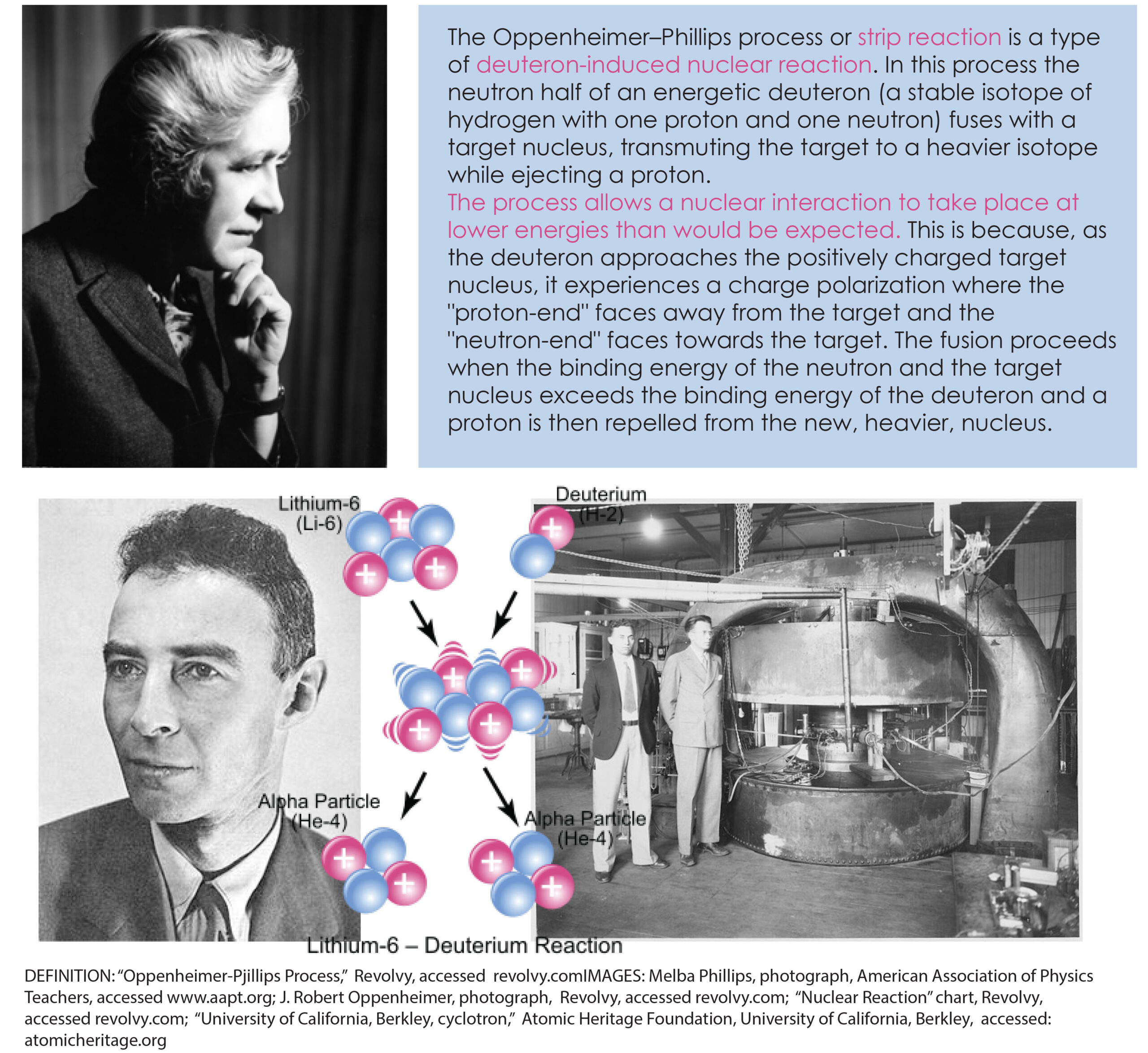

During this period, Phillips and Oppenheimer worked together on problems of theoretical physics, while their colleague Ernest Lawrence’s experiments using the university’s particle accelerator confirmed their theories. In a 1935 paper, Phillips and Oppenheimer proposed a process that was a type of deuteron-induced nuclear reaction, which became a staple of nuclear physics; the New York Times called the discovery a “basic contribution to quantum theory.” [9] This Oppenheimer-Phillips process, as it was called, explained “what was at the time unexpected behavior of accelerated deuterons (nuclei of deuterium, or ‘heavy hydrogen’ atoms) in reactions with other nuclei.” [10] The paper was widely circulated and praised. The Oppenheimer-Phillips process secured Phillips’s place in the history of physics.

Despite her accomplishments and praise from colleagues, Phillips faced challenges. While she had ascended to the peak of her field in a time of unprecedented progress, she bore the historical burden of gender discrimination within that field. According to science writer Margaret Wertheimer, physics has historically been more resistant to women than other scientific fields because of its quest to discover the truths of the universe that descend from theological traditions. While science and religion have been depicted as at odds during the last few centuries, this was not always the case. As the study of physics developed during the Middle Ages, its goal was a religious one: to understand the ultimate truths of the universe through mathematics. It followed then that the social, cultural, and political forces that prevented women from interpreting sacred texts or entering the clergy applied to the field of physics. [11] Some of these prejudices against women remained in the 1930s.

While Phillips clearly had to deal with the burden of exclusion in the field upon her arrival in Berkeley, she was not always comfortable talking about her experience. In interviews she was careful not to insult the many supportive colleagues while speaking of those who were not. Phillips stated:

As in my first college year I was often the only woman in the class, but classes were never large, and the competition was fun rather than otherwise . . . During the five years I lived in Berkeley four women took PhD’s in physics, and perhaps an equal number stopped with the M.A. . . . Were women discriminated against in the department? It did not seem so, certainly not as students. We had teaching fellowships on par with everyone else. It is true that there was one professor who would not take women assistants but it was no hardship to miss that option. [12]

In the same recollection Phillips referred vaguely to “unfair decisions” made by the university about salaries and stipends, but discounted “overt discrimination on account of sex.”[13] Clearly then, Phillips saw that women were not getting equal access to facilities, credit for discoveries, and pay. In fact, physicist and chemist Francis Bonner, who would go on to work on the Manhattan Project, explained that normally such an accomplishment as publishing a new physics principle considered “one of the classics of early nuclear physics,” would have meant a faculty appointment [14]. Phillips received no such appointment. This could be partly because of her gender and partly because of the depressed economy. So perhaps in interpreting the climate at Berkeley at this time, we should use Phillips’s own words whenever possible. She seemed to distinguish between “unfair practices” and “overt discrimination.” And while the former will persist throughout this examination of her career and its challenges, one example of the latter practically jumps off the pages of national newspapers.

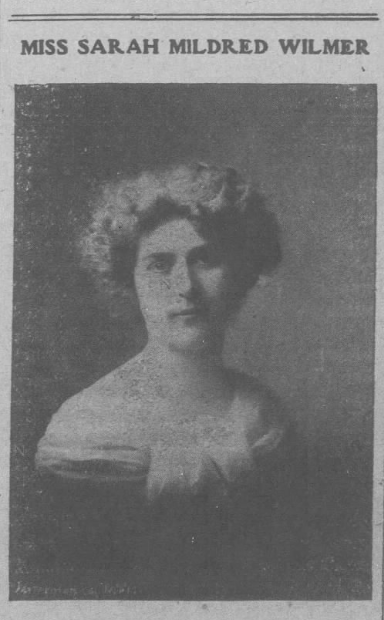

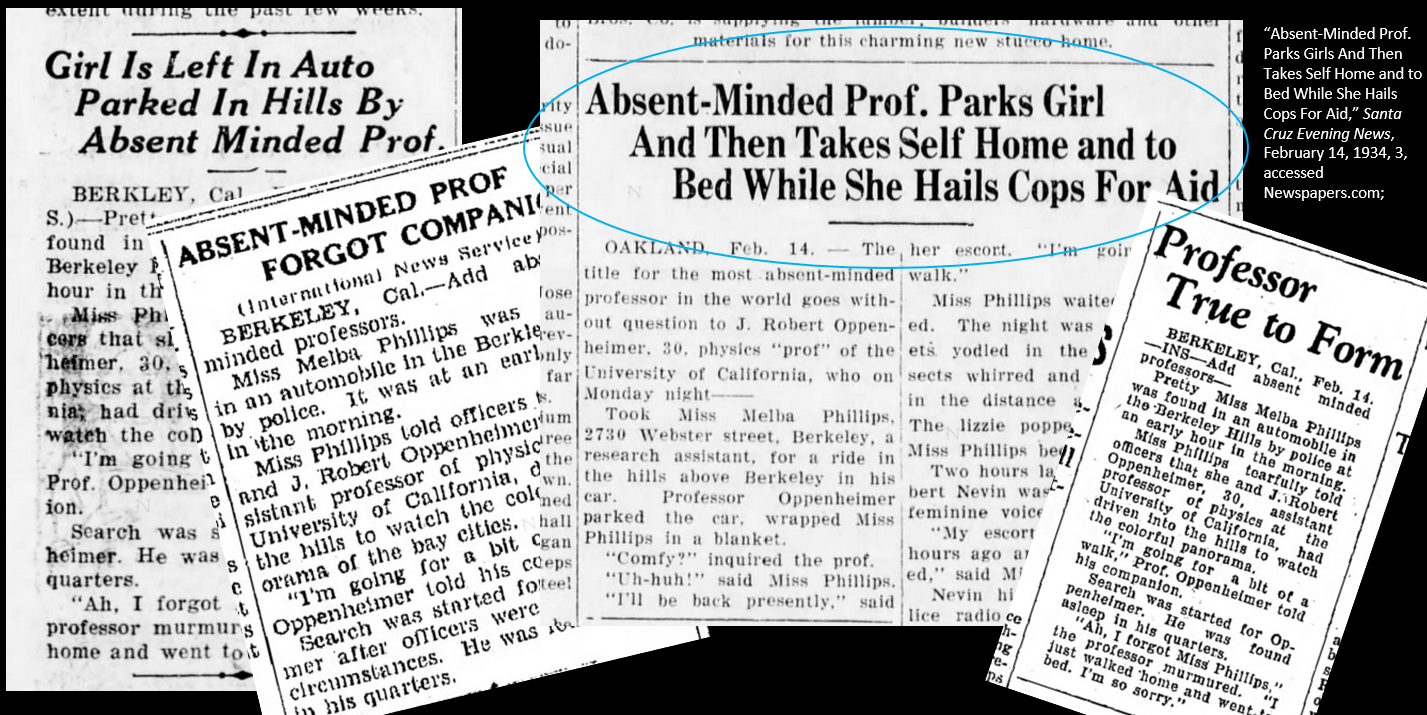

In February 1934, Phillips’s name appeared in headlines across the country, but not for her groundbreaking work in physics. Instead, she appeared in the national press for the first time, infantilized and sexualized as a poor, tearful girl who was nearly scandalized by her professor. This incident is worth examining in some detail not only for further evidence of the prejudice Phillips faced, but also because the story continues to be retold without deeper examination in biographies of Oppenheimer.

On February 14, the Associated Press (AP) reported:

Robert Oppenheimer, 30, physics professor of the University of California, took Miss Melba Phillips of Berkeley, a research assistant, for a ride in the Berkeley hills Monday night. Prof. Oppenheimer then parked the automobile, made Miss Phillips comfortable by wrapping a blanket around her, and said he was going for a walk. Time passed but Miss Phillips waited and waited. Two hours later Policeman Albert Nevin passed by. “My escort went for a walk hours ago and he hasn’t returned,” Miss Phillips told the officer tearfully. [15]

The article continued to state that the police raised an alarm and searched the area to no avail. Eventually, they looked for Oppenheimer at the faculty club where he lived. The AP reported:

And there they found him – fast asleep in bed. “Miss Phillips?” he exclaimed to the officers. “Oh, my word! I forgot all about her. I just walked and walked, and I was home and I went to bed. I’m so sorry.”[16]

The International News Service (INS) also picked up the story, with some minor tweaks. In the INS version “Pretty Miss Melba Phillips was found in an automobile in the Berkeley Hills by police at an early hour in the morning.” Oppenheimer had driven her “into the hills to watch the colorful panorama” of a sunrise. After he was found in his quarters, he supposedly stated, “Ah, I forgot Miss Phillips. I just walked home and went to bed.” [17]

Local newspapers included even more questionable details. One article was titled “Absent-Minded Prof. Parks Girl and Then Takes Self Home and to Bed While She Hails Cops For Aid.” The extra details in this article include the following:

Professor Oppenheimer parked the car, wrapped Miss Phillips in a blanket.

“Comfy?” inquired the prof.

“Uh-huh!” said Miss Phillips.

“I’ll be back presently,” said her escort. “I’m going for a walk.”

Miss Phillips waited and waited. The night was dark. Crickets yodled [sic] in the bushes. Insects whirred and crawled. Off in the distance a dog barked. . . Miss Phillips became jittery. Two hours later Policeman Albert Nevin was hailed by a faint feminine voice.

“My escort went for a walk hours ago and he hasn’t returned,” said Miss Phillips tearfully. [18]

The article–rife with action verbs–concludes with a description of the capable policemen. The cops “hit” the phones, police cars “hurried to the spot,” the men “combed the bushes,” and “searched and sleuthed.” When the article got to the part where they found Oppenheimer at the faculty club, it reported that the professor stated, “Whazzat? Girl? Miss Phillips? Oh, Lord–my word! By George! I forgot all about her.”[19] The implication is that Dr. Phillips, an accomplished physicist and colleague, was solely an object of sexual interest and once the great man’s mind had moved on to other things, she was forgotten, disposable. By emphasizing the “early morning hours” and the automobile parked in a remote location, the newspapers were more than alluding to some sort of sexual relationship. Primary sources refute this allegation.

Phillips’s life experiences and attitude to this point show her as a brave and self-confident young woman. The idea that she would have been tearful because she was left waiting in a car seems unlikely. Also, she was comfortable in nature. She grew up on a farm surrounded by woods where she knew all the wildflowers and where the morels grew. [20] It’s unlikely she was terrified by the “yodel” of crickets. She had successfully navigated much more trying challenges than spending some unexpected time alone by this by this point in her life.

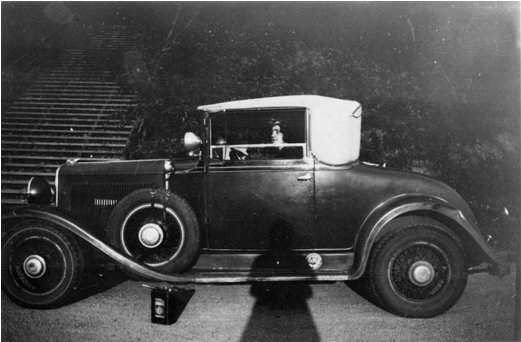

Another reason to doubt the wire services’ version of this story is that Phillips was an experienced driver. Several photographs of Phillips taken at Berkeley show her driving Oppenheimer’s car or posing confidently next to it. Another time, she and another colleague went out driving when they ran over a milk bottle and flattened a tire. Her colleague went to find a mechanic and when they returned Phillips had changed the tire and was relaxing in the car. As her colleague remembered, “Melba could be handy with a wrench.” [21] If Phillips had wanted to go home or go searching for the missing Oppenheimer, she would have felt perfectly comfortable driving the car.

Its perhaps not shocking that newspapers crafted such a salacious story in 1934. What is surprising is that biographers of Oppenheimer continued to cite these articles as evidence of a romantic relationship. For example, the authors of the Pulitzer Prize winning biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer wrote: “For a short time, Robert dated his doctoral student Melba Phillips, and one evening he drove her out to Grizzly Peak, in the Berkeley hills.” The authors then go on to rely on the wire services’ version of events described previously. They cite no other sources as evidence that the colleagues had a romantic relationship. [22]

Further evidence of a strictly collegial relationship comes from Oppenheimer’s letters. Oppenheimer describes Phillips, or “Melber,” as he sometimes called her, as only a professional colleague or simply a friend. In January 1932, Oppenheimer wrote Ernst Lawrence stating that Phillips was doing well and had written him “of some new evidence on the degree of disassociation of potassium . . . Her paper is nearly written up.”[23] In the Fall of 1932, he wrote his brother Frank that “Melber and Lawrence,” among others, “send you greetings.”[24] In January 1935, he wrote his brother concerning theoretical physics problems and noted that “as soon as I get back to Berkeley Melber & I will have a careful look at the calculations.”[25] In Spring 1935, he wrote Lawrence concerning the paper that would define the Oppenheimer-Phillips Process: “I am sending Melba today an outline of the calculations & plots I have made for the deuteron transmutations functions.”[26] In this letter, he noted that Phillips was working out the math calculations for the problem. There is no evidence in these published letters of anything but Oppenheimer’s respect for Phillips as a colleague.

In short, the portrait of Phillips painted by these articles looked nothing like the accomplished physicist and confident young woman she had become. In February of 1934, when these articles ran, Dr. Phillips had completed and defended her Ph.D. dissertation and published a series of papers in academic journals on multi-electron atoms. She was also working for the university as a part-time instructor, while she and Oppenheimer developed their famous process on the “transmutation function for deuterons” and preparing it for publication. But in her first appearance on the national stage, predating the publication of the Oppenheimer-Phillips process by only a few months, she was pretty, helpless, tearful Miss Melba Phillips, the forgotten assistant. Newspapers across the country were still running the article as late as March.

Despite this wound to her pride, Phillips continued to achieve within her field and went on to become an influential physics educator. But many challenges still lay ahead of her, including advocating for the peaceful application of nuclear energy in the wake of the atomic bomb and facing a Senate subcommittee charging her with communist affiliation during the McCarthy Era. There is much more to learn about Melba Phillips. Check out the state historical marker, additional blog posts, and this podcast episode to learn more. Or maybe we will see you at the movies this week to see Phillips’s friend Oppenheimer on the big screen.

Notes:

[1] Randy Mills, “A Source of Strength and Inspiration: Melba Phillips at Oakland City College,” Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History 30, No. 3 (2018): 38-45.

[2] Dwight E. Neuenschwander and Sallie A. Watkins, “In Appreciation: Professional and Personal Coherence: The Life and Work of Melba Newell Phillips,” Physics in Perspective 10 (2008): 295-364, accessed INSPIRE, Indiana State Library.

[3] “Our History,” Berkeley Physics, University of California, Berkeley, accessed physics.berkeley.edu/about-us/history.

[4] “Oppenheimer: A Life,” J. Robert Oppenheimer Centennial Exhibition, Office for History of Science and Technology, University of California, Berkeley, accessed cstms.berkeley.edu/.

[5] Neuenschwander and Watkins, 305-8.

[6] Ibid., 305.

[7] J. Robert Oppenheimer to May L. Cheney, April 10, 1933 in Neuenschwander and Watkins, 308.

[8] Neuenschwander and Watkins, 302. The authors quote a private letter.

[9] “J. Robert Oppenheimer, Atom Bomb Pioneer, Dies,” New York Times, February 19, 1967, 1, accessed timesmachine.nytimes.com.

[10] Press release, “Melba Phillips, Physicist, 1907-2004,” University of Chicago News Office, November 16, 2004, accessed http://www-news.uchicago.edu/releases/04/041116.phillips.shtml.

[11] Margaret Wertheim, Pythagoras’ Trousers: God, Physics, and the Gender Wars (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1995), 9.

[12] Melba Phillips, “Studying Physics in the Thirties – A Personal Recollection,” April 24, 1978, Folder 2: Correspondence, 1948-1999, Box 1, Niels Bohr Library & Archives, American Institute of Physics.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Press release, “Melba Phillips, Physicist, 1907-2004,” University of Chicago News Office, November 16, 2004, accessed http://www-news.uchicago.edu/releases/04/041116.phillips.shtml.

[15] “Professor in Adage’s Proof,” Sun Bernardino County Sun, February 14, 1934, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; “Absent Minded Professor Leaves Girl in Car, Walks Home and Retires,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 14, 1934, 13, accessed Newspapers.com.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “Professor True to Form,” Indiana (PA) Gazette, February 14, 1934, accessed Newspapers.com; “Girl Is Left in Auto Parked in Hills By Absent Minded Prof,” (Lebanon, PA) Evening Report, February 14, 1924, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[18] “Absent-Minded Prof. Parks Girls And Then Takes Self Home and to Bed While She Hails Cops For Aid,” Santa Cruz Evening News, February 14, 1934, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Lisa L. Williams to Randy Mills, July 13, 2018, personal collection of Randy Mills, professor emeritus, Oakland City University.

[21] Neuenschwander and Watkins, 305.

[22] Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (2006), 95-96.

[23] J. Robert Oppenheimer to Ernest Lawrence, January 3, 1932 in Alice Kimball Smith and Charles Weiner, eds., Robert Oppenheimer: Letters and Recollections (Harvard University Press, 1980), 147.

[34] J. Robert Oppenheimer to Frank Oppenheimer, Fall 1932 in Kimball and Weiner, 157-8.

[25] J. Robert Oppenheimer to Frank Oppenheimer, January 11, 1935 in Kimball and Weiner, 189.

[26] J. Robert Oppenheimer to Ernest Lawrence, Spring 1935 in Kimball and Weiner, 193.