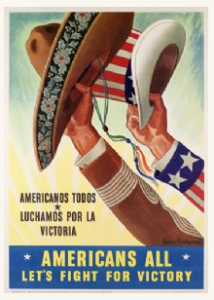

Every election elicits charges of voter fraud. During the 2016 general election, Republicans charged Democrats with importing out-of-state voters to swing New Hampshire. During the 2018 midterms, Democrats charged Republicans with disenfranchising African American senior citizens who needed rides to the polls. The courts can decide the individual cases, but the accusations show us that people have always been concerned about who is a legitimate voter, and therefore, citizen.

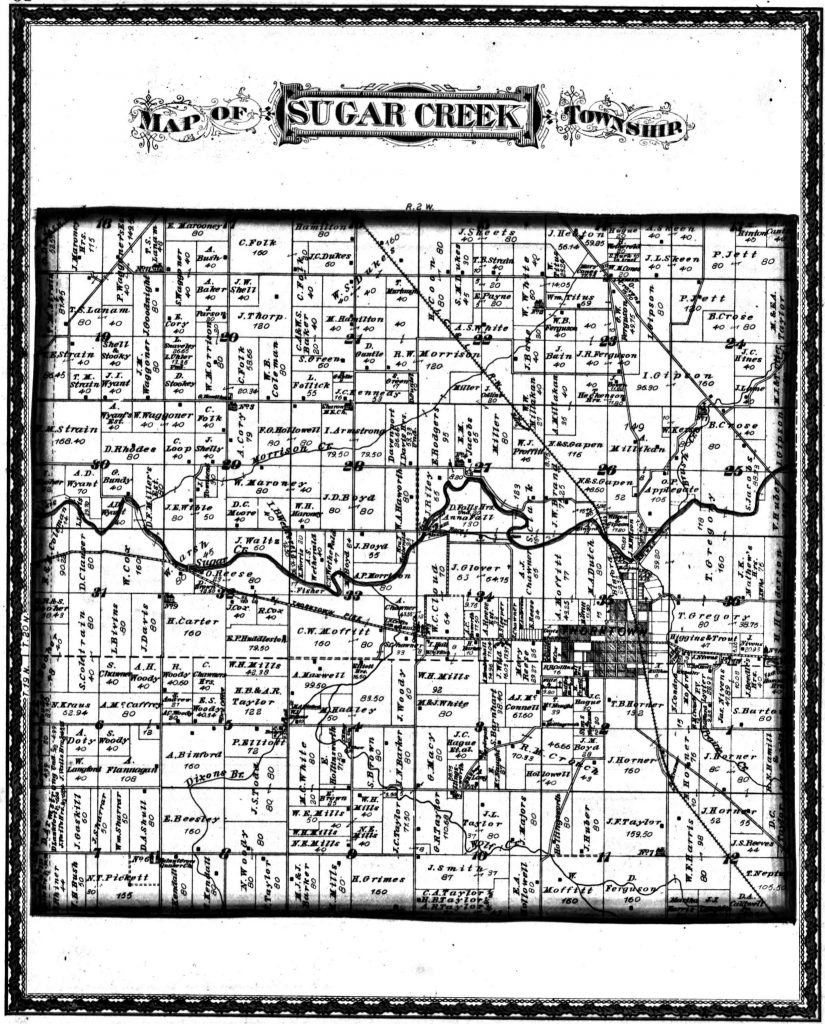

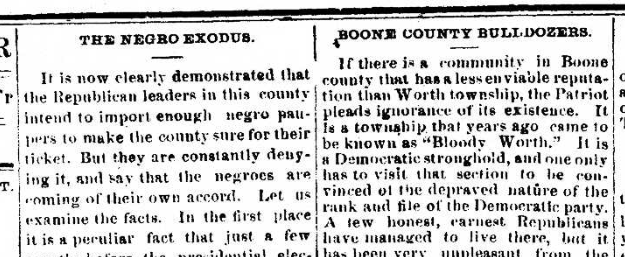

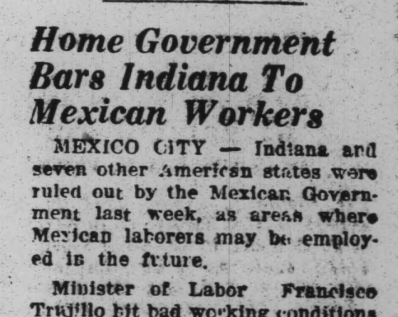

In 1880, the democratic newspaper of Lebanon, Boone County, published a ranting article accusing Republicans of voter fraud. The Lebanon Weekly Pioneer claimed that Republicans at the state level imported Black men from North Carolina to Boone County to win a legislative seat for the region. The charge was ludicrous. Black families had established a thriving farming community around Thorntown in the Sugar Creek Township of Boone County as early as the 1840s. But the article showed more than the prejudice of the local editor, who saw this community as “imported,” as “other,” and as not “real” or “true” Boone County voters. The article reflected the fear of the white, democratic newspaper’s audience. These white citizens were afraid of losing their sovereignty. Because whether or not the Pioneer considered Black Hoosiers to be “real” voters, the Black men of Boone County held real political power. [1]

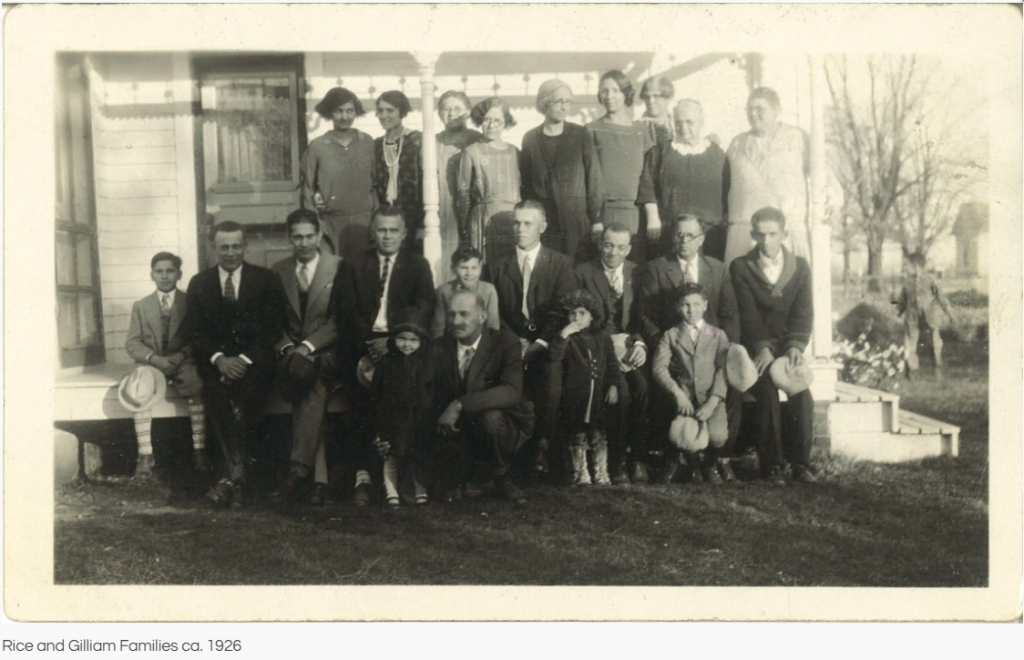

By the 1840s, patriarch Moody Gilliam moved his large family, described as “mulatto” by white census takers, from North Carolina to Boone County, Indiana. Other members of the Gilliam family had been prominent in the establishment of nearby Roberts Settlement in Hamilton County. This proximity to family and another black community certainly played an important part in the decision to settle and farm in Boone. The Gilliams owned at least $1000.00 worth of property by 1850 which they farmed and improved successfully. By 1860, Moody Gilliam’s property was estimated at $4000.00. This would be approximately $120,000 today, a solid foundation for a family facing unimaginable prejudice and legal discrimination. [2]

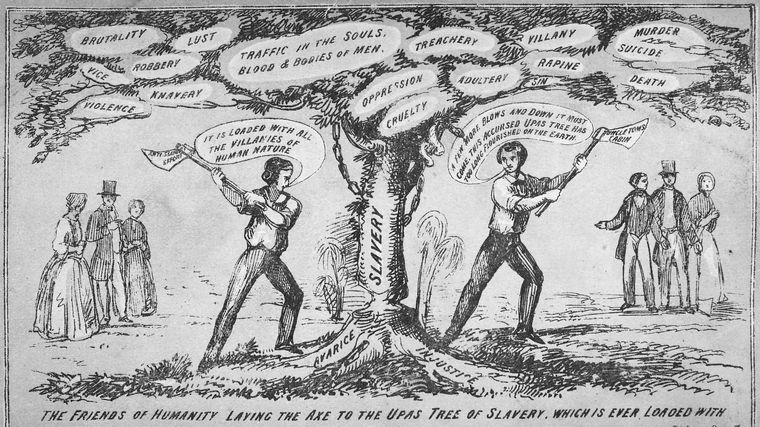

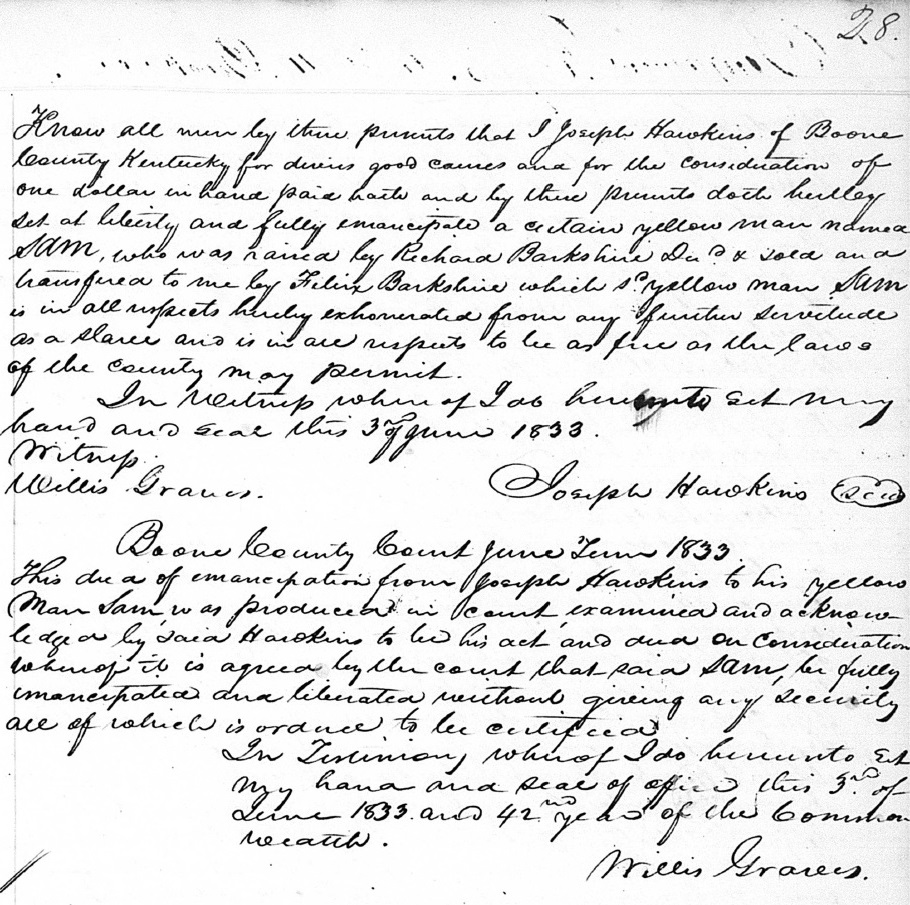

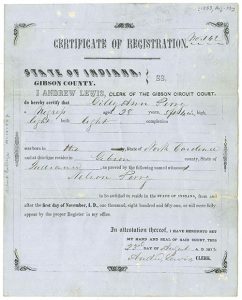

Though he was a well-to-do land owner by 1860, Moody Gilliam would not have been allowed to vote. Additionally, he may have been forced to register with county authorities and to post a $500 bond with the assumption that the county would someday be supporting him. In fact, Indiana residents made it clear that they did not even want him there at all. In 1851, Hoosiers voted for Article XIII of the Indiana Constitution that stated, “No negro or mulatto shall come into, or settle in the State, after the adoption of this Constitution.” Despite racist legislation and prejudice, Black settlers established a successful farming community in Boone County concentrated in Sugar Creek Township near Thorntown.

By 1860, seventy-two Black Hoosiers lived in Sugar Creek Township with eleven based in Thorntown proper. The census from that year, shows us that they arrived mainly from North Carolina and Kentucky, that they were predominately farmers, and that most could not read and write. Many Black Southerners had been prohibited from obtaining an education as it was seen by white slave owners as a threat to the slavery system. The mainly illiterate founders of the Sugar Creek settlement, however, broke this systematic oppression by making sure their children could read and write.

By the late 1860s, Sugar Creek residents of color purchased land from local Quakers for the purpose of building a school, likely at the corner of Vine and Franklin Streets in Thorntown. Around the same time, they also purchased a lot to build an A.M.E. church at the west end of Bow Street. The church established a Sabbath school around 1869. Thus, the children Sugar Creek’s founders received a primary education as well as a spiritual one. By 1869, residents purchased more Quaker land to establish a “burying ground for the Colored people of Thorntown and vicinity.” It was clear that they planned on staying. [3]

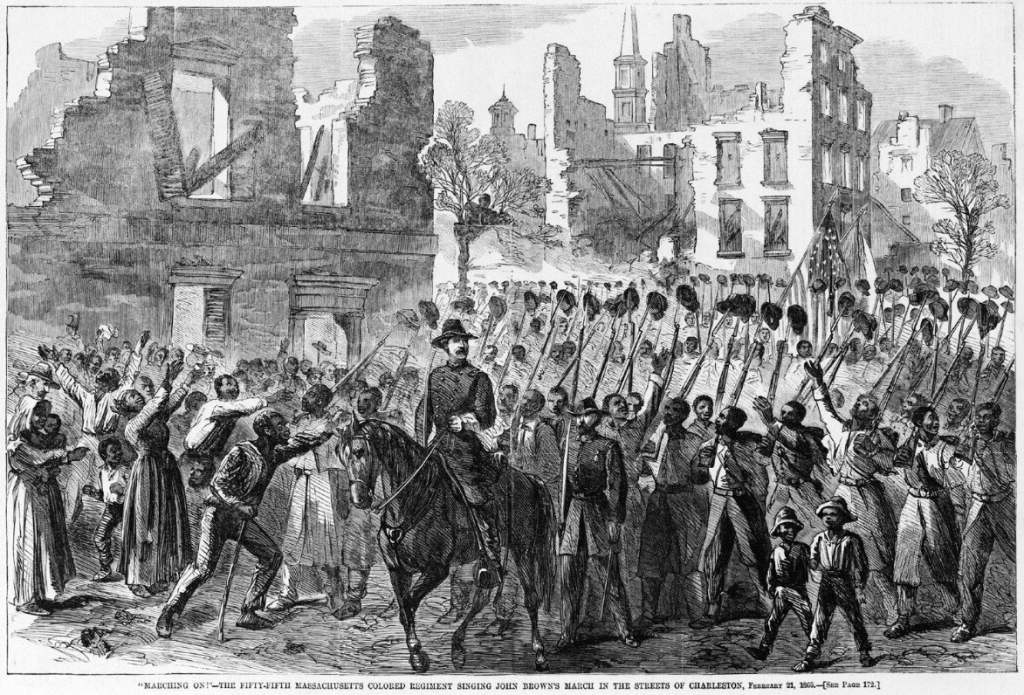

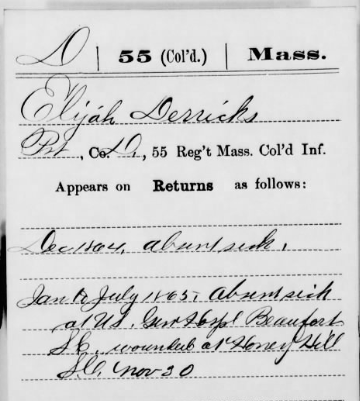

During the Civil War, at least one Sugar Creek son fought for the Union cause in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment of the United States Colored Troops. It’s not clear when Elijah Derricks came to Sugar Creek, before or after the war, but he is buried in the “colored cemetery.” Derricks volunteered for service in 1863 when he was 38-years-old. His regiment saw a great deal of action in Florida and South Carolina.

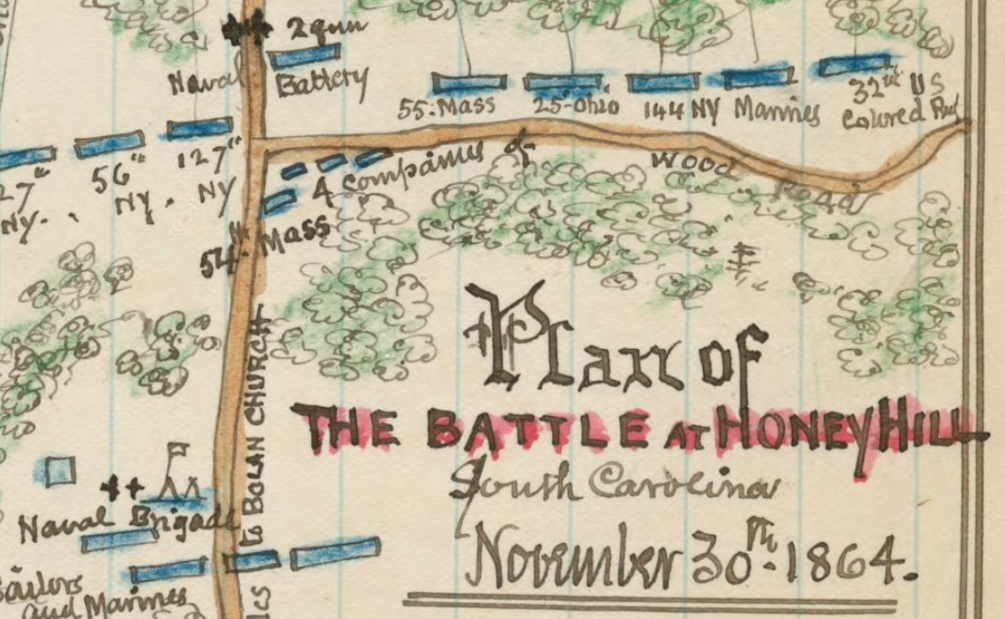

All Civil War units struggled with causalities from disease and Derricks suffered several bouts of illness, but returned to his regiment each time. In November 1864, he was injured at the Battle of Honey Hill, a Union initiative designed to help Sherman’s March to the Sea. It’s not clear if Derricks’ injury took him out of action or if he remained with the regiment until it mustered out. If he did remain, he would have been present in 1865 when the 55th marched into a conquered Charleston, arriving “to the shouts and cheers of newly freed women, men, and children.”[4] Either way, Derricks carried his injury for life, as he collected a pension for his injured arm back at Sugar Creek. [5]

By the late 1860s, the Sugar Creek community also boasted a Masonic lodge. By 1874, they had seventy-four members and the Boone County Directory listed the group as: Washington Lodge F&AM (Colored). While not much is known about “the colored Masons of Thorntown,” their establishment of such a society shows us that they sought power through organization. However, the men of Sugar Creek also took more direct political action. [6]

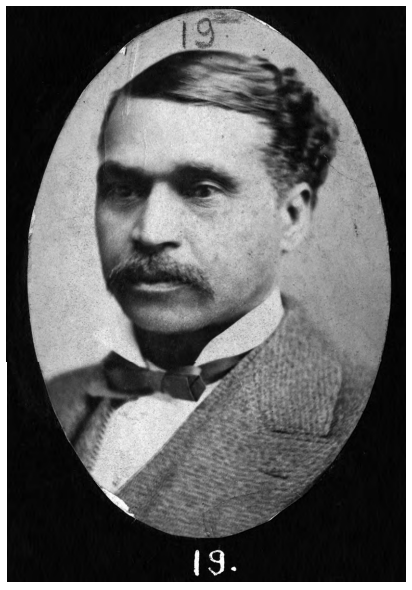

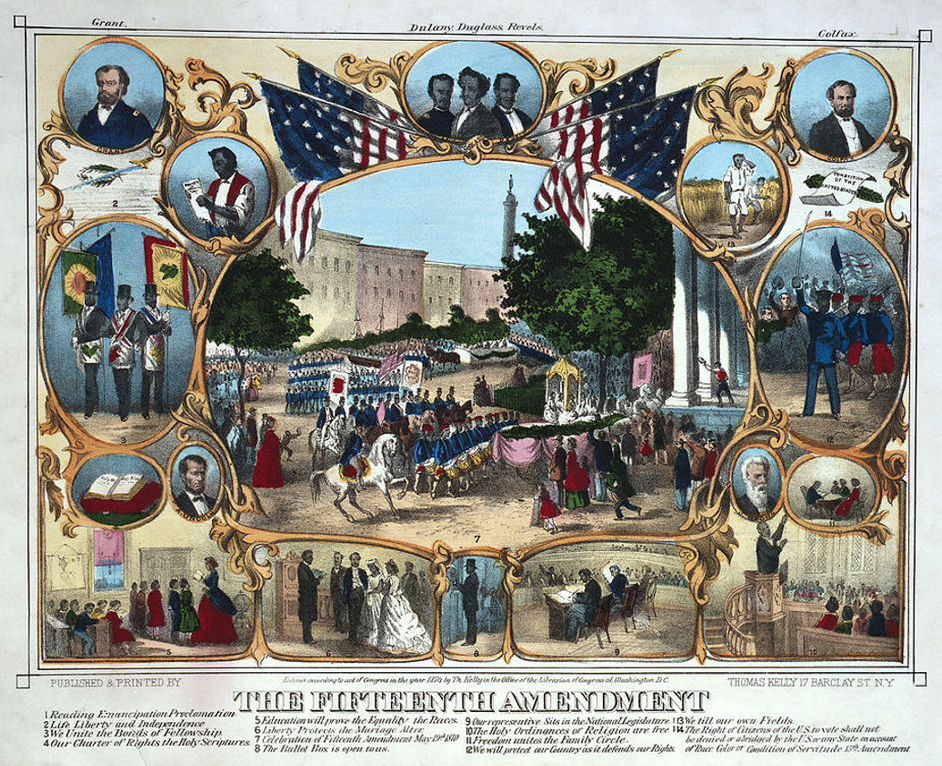

While the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gave Black men in the North the right to vote in 1870, one newspaper article implied that some residents of color in Sugar Creek participated in local elections prior to this legislation. The Thorntown Argus reported in 1897 that after the well-liked and respected barber John Mitchell settled in Thorntown around 1864, “he was a delegate to the first Republican county convention held after his arrival and there were 47 colored voters in this township then”[7] The newspaper’s language is ambiguous, but seems to imply that they were voting in the 1860s before the amendment passed. [8]

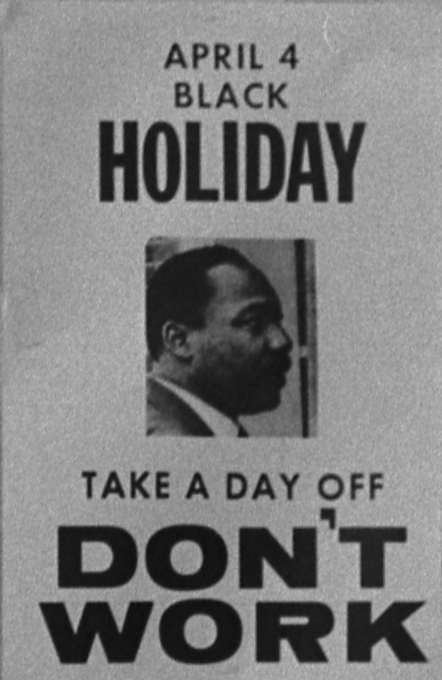

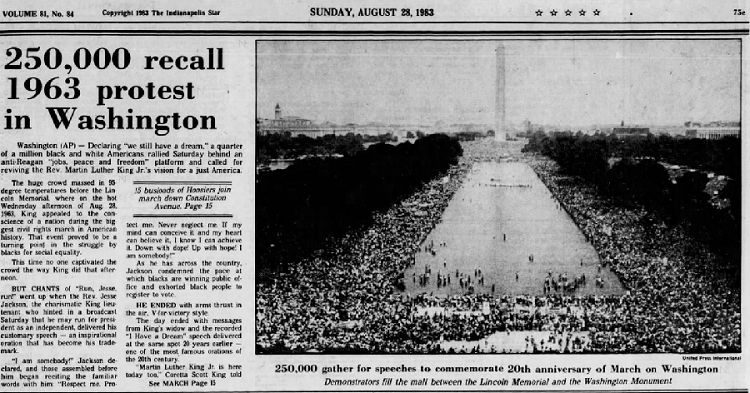

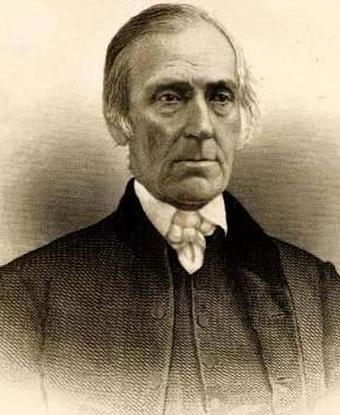

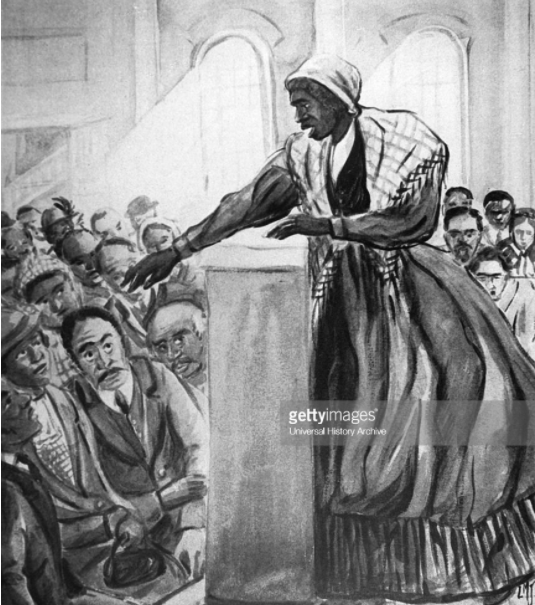

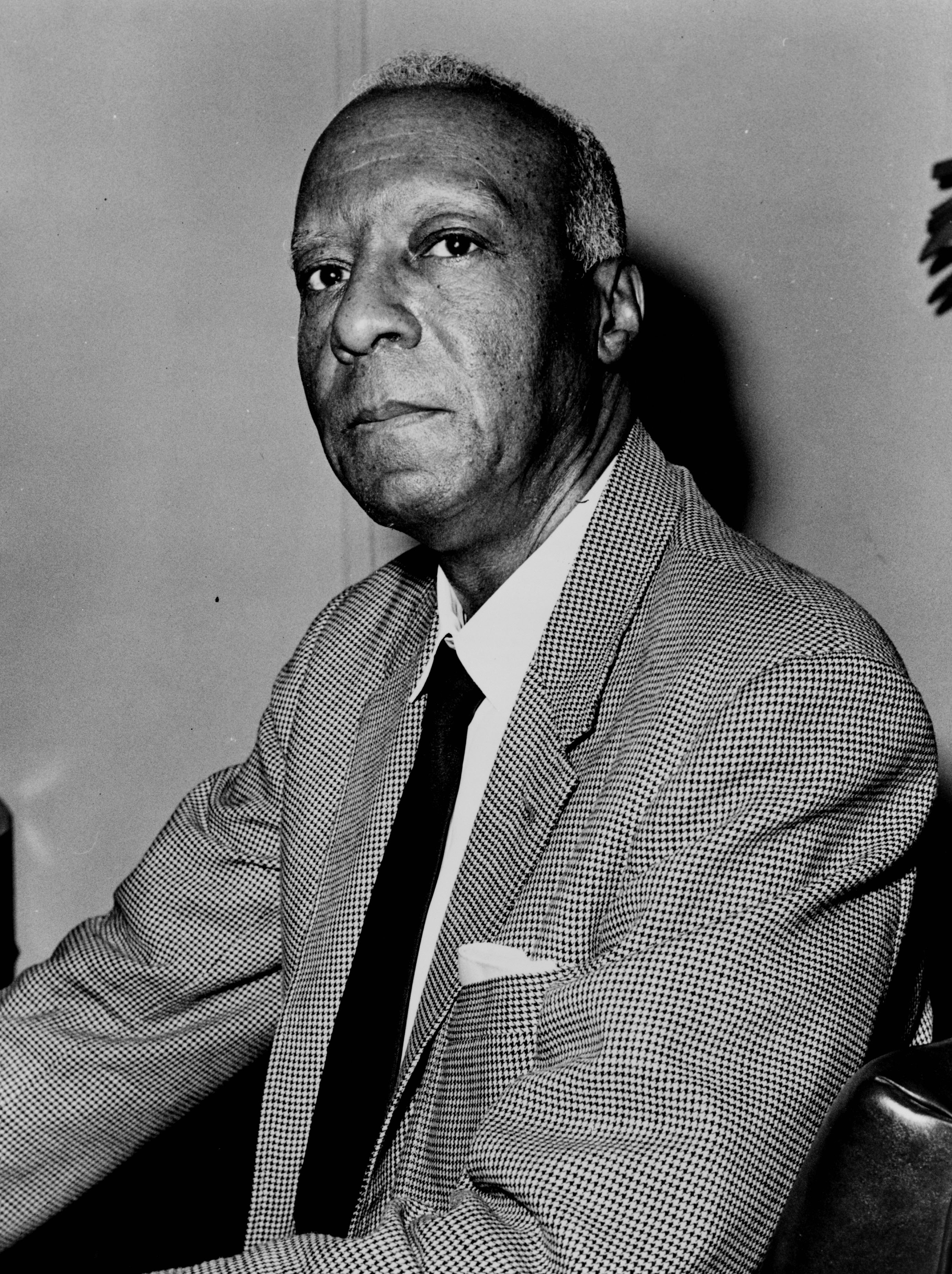

After officially gaining suffrage rights, however, the men of color in the community immediately joined the political efforts and causes of the time. On Saturday, August 10, 1870, they held a large “XVth Amendment celebration” at Thorntown. [9] One of the speakers that day was the James Sidney Hinton, a powerful orator and civil rights advocate who would become the first African American to serve in the Indiana General Assembly. There is no record of what the Republican leader said to the people of Thorntown the day they celebrated their enfranchisement. However, gleaning from a speech he made some years later on Independence Day, we can imagine he made similar remarks. Hinton stated on that occasion: “The forces of truth and the principles of liberty, born in the days of the revolution, and proclaimed in the Declaration of 1776 have placed the negro for the first time in his history on this continent in a position to realize that he is a man and an American citizen.” [10]

In 1872, several prominent men of the Sugar Creek community founded a political organization. The Lebanon Patriot reported that “the colored men of Thorntown were organized into a Grant club at Thorntown” which hosted political speakers. [11] The Crawfordsville newspaper referred to it as the “Gran Wilson Club,” making clear that they were advocating for the Republican presidential ticket during the election season. [12] Despite the more blatantly racist policies of the Democratic Party at the time, not all Black residents of Sugar Creek were Republicans. In 1896, “Rev. Charley Derrickson of Thorntown, colored, 90 years of age, took part in several Bryan parades during the campaign.” [13] While this three time presidential candidate was never an advocate for Black citizens, perhaps the reverend found something he liked in William Jennings Bryan’s Protestant values.

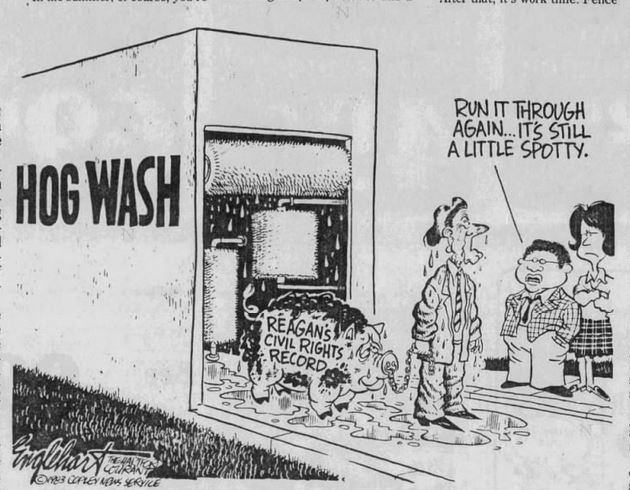

By the late 1870s, local newspapers provided evidence of the power of the Black vote in the area. The Lebanon Pioneer described (and poked fun at) the candidates for local offices of Sherriff, County Recorder, and County Auditor. The newspaper implied that the candidates were Quakers and noted that only one of the candidates by the last name of Thistlethwait could “hold a solid negro vote.” The support of the Black vote, the newspaper concluded, was needed for Thistlethwait to win the election and was only possible for him if local resident of color, Harvey White, “sticks to him.” [14] The Pioneer was staunchly Democrat and often blatantly racist, so it is quite possible that these statements were meant to discredit the candidate. However, it does show the weight of Black leadership and suffrage in the district.

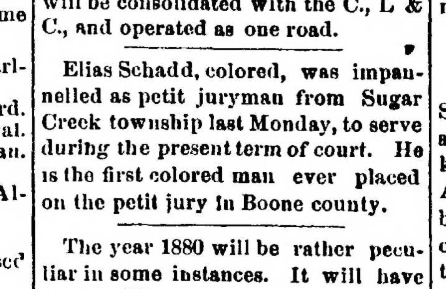

This increased influence of the Black vote was due in part to an increase in population. By 1870, 172 Black Hoosiers lived in Sugar Creek Township, seventy-seven of whom lived in Thorntown. The A.M.E. church had twenty-five adult congregants by 1874 and forty-five children in Sunday school. In 1879, the local newspaper reported that “Elias Schadd, colored, was impaneled as a petit juryman from Sugar Creek Township last Monday, to serve on the present term of court. He is the first colored man ever placed on the petit jury in Boone County.” [15] Thorntown was growing and changing, and for some white residents, this felt threatening.

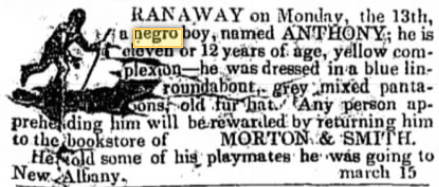

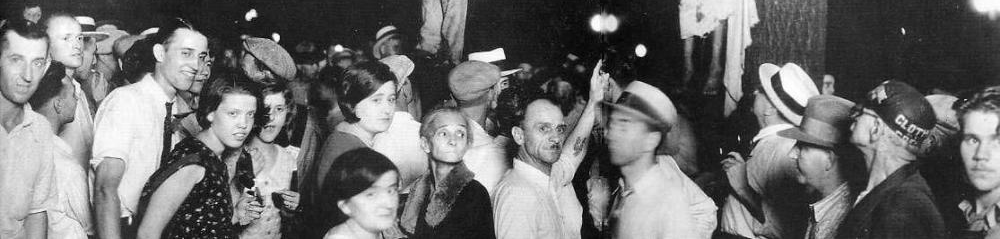

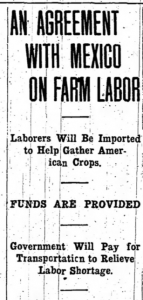

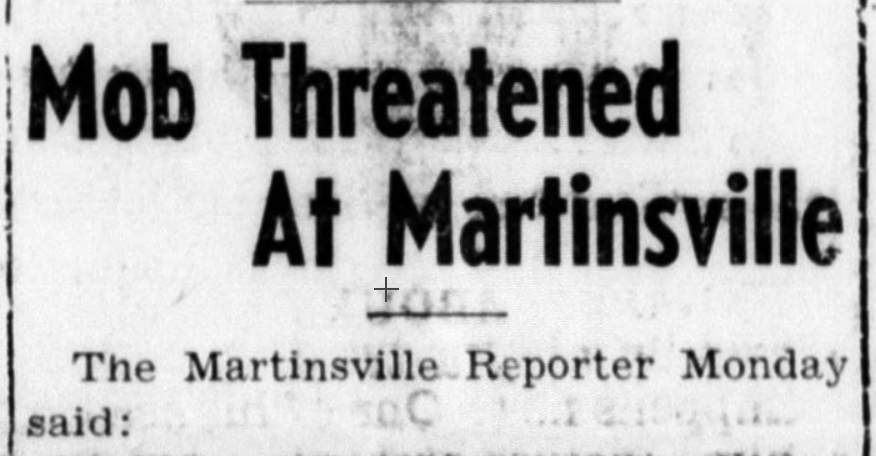

In nearby Whitestown, Boone County, white residents carried out “an unprovoked attack on a colored family.” According to the Lebanon Patriot, the family arrived on Thursday January 29, 1880, and “took refuge in an old dwelling house.” A mob surrounded the house the following evening and “showered the building with stones and brick-bats.” When the family was forced out of the structure, one of the children was “seriously injured” by a brick. The mob successfully “forced the family to leave town.” The Patriot reported that the attack was instigated by reports that Republicans were importing voters to Boone County. The paper dismissed the charges against republicans, stating that the patriarch of the unnamed family “had gone there of his own notion” and “the attack was wholly unwarranted.” [16]

The Democratic paper, the Lebanon Pioneer, attacked the Lebanon Patriot’s report of the incident with racist vitriol and slurs. The Pioneer reported that the Black man’s name was “Thusa” and that a white resident named “Mr. Scovill” lent him a stove and asked him several questions. The Pioneer reported on their supposed exchange. Thusa “said he had come from North Carolina, and that he had come to vote with the ‘publican party.’” Scovill asked him if he had any money or clothes to which he reportedly replied “no, sah.” The paper concluded, “He was a pauper, and imported as such, and the only reason he could give, was to vote the ‘publican’ ticket.” The newspaper claimed Whitestown was fed up with supporting such paupers and played down the physical attack, claiming the mob threw stones only at the house, and never mentioned the man’s wife or children. The Pioneer claimed the attack continued “until the colored occupant became so frightened as he agreed to leave the town . . . no one was hit or hurt.” [17]

In the same issue, the Lebanon Pioneer, printed a more extensive article charging Indiana Republicans with importing Black voters from North Carolina. Their entire argument hinged on the claim that if these Black settlers were coming of their own volition, they would never come to Boone County, Indiana. The paper asked:

If it is not for political purposes why do they come so far? Why don’t they stop in Pennsylvania or Ohio? And if the colored people are so anxious to come to Indiana, why don’t they come from Kentucky or Missouri. At least a few.

The Pioneer‘s argument was baseless. Of course, many people came from North Carolina, because they were joining family who came from North Carolina – a migration pattern that has existed for as long as migration has been recorded. And they did come from other states, especially Kentucky. In fact, about half of the residents of Sugar Creek were originally from the neighboring Blue Grass State. And some did come from Virginia and even New York.

Nonetheless the Pioneer stated:

It is a fact: they have brought them to Boone county. Republican leaders are doing it for the purpose of making sure of the county ticket and send a Republican to the legislature.

The paper concluded that these “stupid paupers” would “override the majority of real and true Indianians.” First of all, any true “Indianian” would have used the word “Hoosiers.” [18] Second, and all joking aside, there were few paupers or criminals among the Sugar Creek community. There were instead farmers, washer women, school teachers, reverends, barbers, ditch diggers, students, and veterans. [19] And despite all of the institutionalized prejudice, and against the odds, for many generations they created a healthy community in Sugar Creek, Boone County.

By the late 1890s, many of the Sugar Creek community had moved to Lebanon or surrounding towns for more employment opportunities. However, the Thorntown church stayed active for several more decades. In 1894, the Thorntown Argus reported that “the colored church” would serve as the polling place for the second precinct of Sugar Creek Township. [20] In 1898, the congregation raised money and built a brick parsonage building to house their reverend in comfort. In 1902, they held a successful New Year’s concert and fundraiser. That year, the Indianapolis Recorder reported on the “good work” of the Literary Society and Sunday school and noted that the women of the AME congregation organized a Missionary Society. [21] Unfortunately, there are few records of the lives of the women of Sugar Creek. Census records show that many had large families and thus were mainly engaged in child care, as well as helping with the farm. Thus, the work of the missionary society is perhaps our best insight into the lives of the women of Sugar Creek. These women organized programs and social gatherings at the church and engaged in community service. They raised money for a new carpet for the church. The ladies held “a successful social” after the organized theological debate held at the church and their programs were known for being “excellent” even forty miles away in Indianapolis. They led the memorial services for one congregate in which they were “assisted” by the revered, as opposed to the other way around. [22]

Today, the only known physical remnant of the Sugar Creek Community is the small cemetery where the Civil War veteran Elijah Derricks is buried under a worn headstone. This is all the more reason to continue looking into this story. There is more here – to add, correct, and uncover. Thorntown librarians, genealogists and Eagle Scouts have been working to learn more, and the descendants of Roberts Settlement have shown that genealogical research can open up a whole new world of stories. [See related local projects] But even with what little we do know about Thorntown and Sugar Creek, the community stands as a powerful reminder to check prejudice against newcomers. Before they could vote, or testify in court, or expect a fair shot, Black settlers built a thriving community in Sugar Creek. They worked, raised families, built a school, celebrated their accomplishments, worshiped together, and perhaps most importantly, they cast their ballots.

*Note on Terminology: The term “Black” is used here as opposed to “African American” because it provides the necessary ambiguity to describe the Sugar Creek settlers. Some family names at Sugar Creek are the same as residents of Roberts Settlement and thus likely relatives. Many Roberts residents either had no African heritage or very distant and thus did not identity as “African American.” Describing the Sugar Creek settlers as “Black” is more inclusive of the possibility that Sugar Creek residents had the same heritage as Roberts residents.

Notes

[1] Lebanon Weekly Pioneer, February 5, 1880.

[2] 1850 and 1860 United States Census accessed AncestryLibrary.

[3] Deed Record Book 15, Records of Boone County Recorder’s Office.

[4] Ephrem Yared, “55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment,” Black Past, March 15, 2016, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/55th-massachusetts-infantry-regiment-1863-1865/

[5] Lebanon Weekly Pioneer, October 11, 1883.

[6] Crawfordsville Weekly Journal, July 9, 1868.

[7] Thorntown Argus, March 6, 1897

[8] More on the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment and Hoosier response: Indiana Historical Bureau

[9] Lebanon Patriot, September 15, 1870.

[10] “James Sidney Hinton,” accessed Indiana Historical Bureau.

[11] Lebanon Patriot, August 8, 1872.

[12] Crawfordsville Weekly Journal, August 15, 1872, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[13] Indianapolis Sun, November 3, 1896.

[14] Lebanon Pioneer, July 19, 1877.

[15] Lebanon Pioneer, November 27, 1879.

[16] Lebanon Weekly Pioneer, February 5, 1880.

[17] Lebanon Weekly Pioneer, February 5, 1880.

[18] Lindsey Beckley, “The Word ‘Hoosier:’ An Origin Story,” Transcript for Talking Hoosier History, Indiana Historical Bureau.

[19] 1850 and 1860 United States Census accessed AncestryLibrary.

[20] Thorntown Argus, November 3, 1894.

[21] Indianapolis Recorder, April 19, 1902, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[22] Indianapolis Recorder, April 19, 22, May 3, 17, 1902, Hoosier State Chronicles.

Further Reading

Anna-Lisa Cox, The Bone and Sinew of the Land (New York: PublicAffairs, 2018).

Warren Eugene Mitleer Jr., The Complications of Liberty: Free People of Color in North Carolina from the Colonial Period through Reconstruction, Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Carolina Digital Repository, accessed cdr.lib.unc.edu.

Emma Lou Thornbrough, The Negro in Indiana before 1900 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1985).

Stephen A. Vincent, Southern Seed, Northern Soil: African-American Farm Communities in the Midwest, 1765-1900 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999).

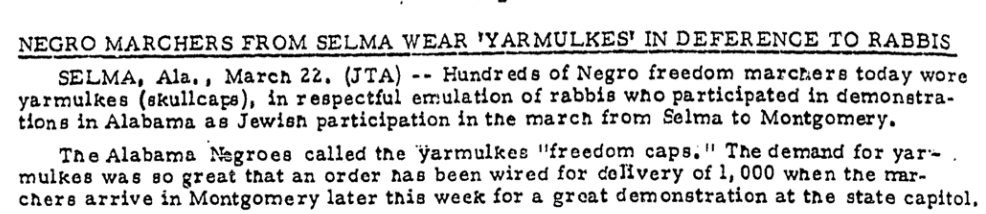

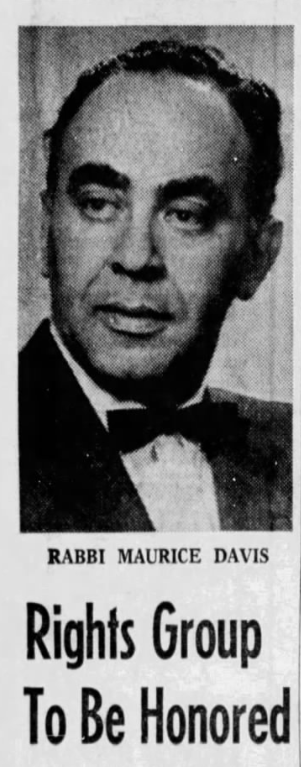

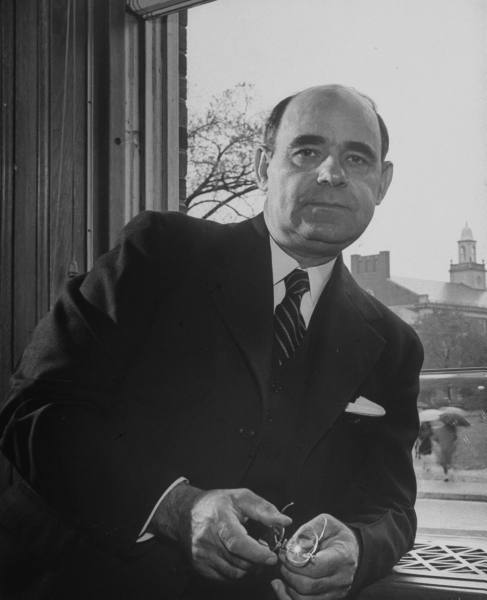

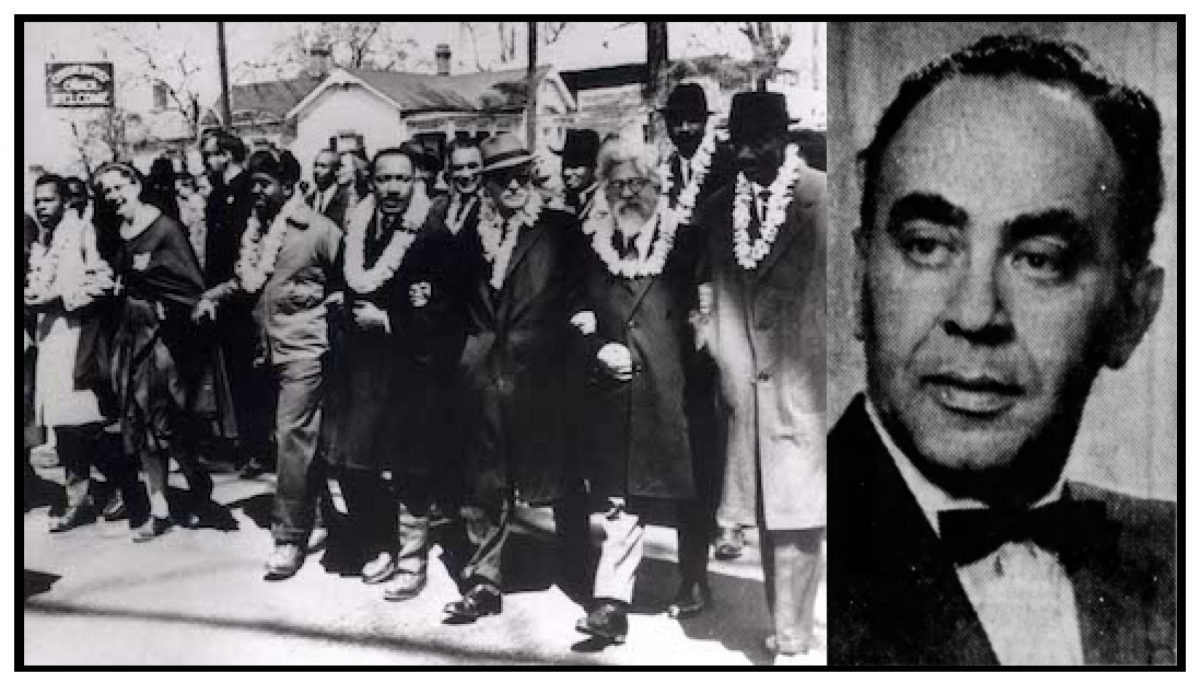

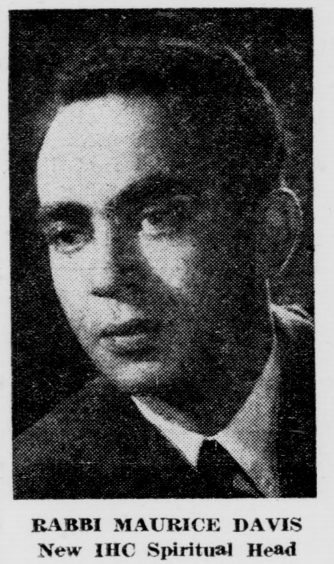

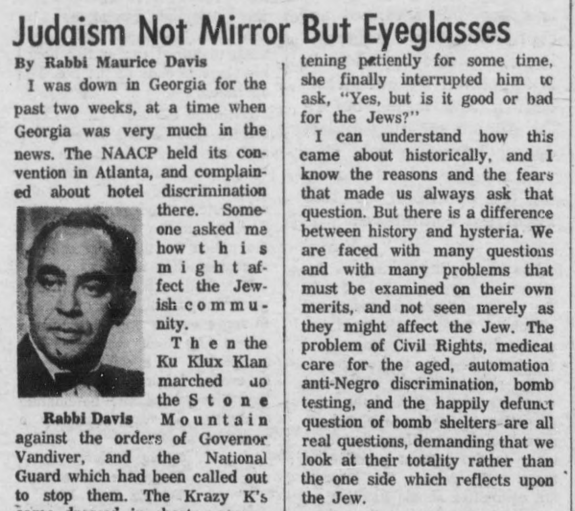

Maurice Davis was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1921. Census records show that his Russian-born father Jacob managed a garage while his mother Sadie cared for five children. They did well for themselves and were able to send Maurice first to Brown University in 1939 and then to the University of Cincinnati where he received his B.A. in 1945. He then received his Master of Hebrew Letters from the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. After serving several different congregations as a student rabbi, he became rabbi of Adath Israel in Lexington, Kentucky in 1951. By this point he was already active in the local civil rights movement and joined the Kentucky Commission Against Segregation.

Maurice Davis was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1921. Census records show that his Russian-born father Jacob managed a garage while his mother Sadie cared for five children. They did well for themselves and were able to send Maurice first to Brown University in 1939 and then to the University of Cincinnati where he received his B.A. in 1945. He then received his Master of Hebrew Letters from the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. After serving several different congregations as a student rabbi, he became rabbi of Adath Israel in Lexington, Kentucky in 1951. By this point he was already active in the local civil rights movement and joined the Kentucky Commission Against Segregation.

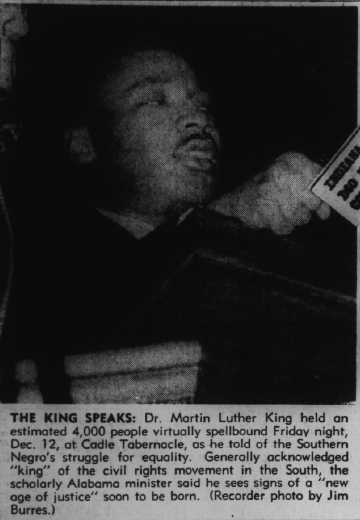

Rabbi Maurice Davis became the spiritual leader of the

Rabbi Maurice Davis became the spiritual leader of the

Rabbi Davis not only advocated for equality for Jews, but all people facing oppression. He encouraged Jews to look beyond their own community and work to end discrimination everywhere. He stated, “A decent and sensitive America is good for all Americans and we must help her be so” (

Rabbi Davis not only advocated for equality for Jews, but all people facing oppression. He encouraged Jews to look beyond their own community and work to end discrimination everywhere. He stated, “A decent and sensitive America is good for all Americans and we must help her be so” (

His columns were often fiery calls to action. For example, in September 1963, he

His columns were often fiery calls to action. For example, in September 1963, he