Scholar and reformer Sarah Parke Morrison is best remembered as the first female student and then professor at Indiana University. But she took on the role of trailblazer reluctantly, as she feared being the target of backlash against this furthering of women’s equality. Her fears were not unfounded. Unsurprisingly perhaps, she faced discrimination as she entered this previously all-male space. What was surprising as we dove into research for a new state historical marker honoring Morrison, was the intensity of the vitriol that some male students directed toward this groundbreaking scholar. While Morrison would continue to work to advance women’s educational opportunities at IU, she was for a time, driven from from her chosen profession by these students’ misogyny. Despite this difficulty, Morrison’s willingness to serve as the first woman at IU opened the doors for the many women who followed, each one furthering the cause of equality.

This and other stories of defeats, setbacks, small advancements, and modest gains are also important to women’s history as they show us the breadth of the movement and the perseverance required of its pioneers – women who challenged injustice in their small realm of influence. These local efforts, multiplied by the work of women across the United States, eventually created a sea change in women’s rights, roles, and power.

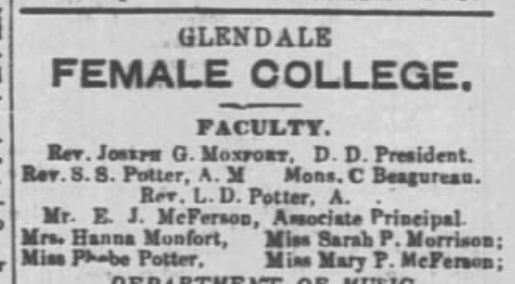

Sarah Parke Morrison was born in Salem, Indiana, in 1833, into a family that highly valued education and believed in equal opportunities for women. In 1825, her parents opened Salem Female Seminary and hired female teachers, “a rarity at this time.”[1] After extensive study at home with her professor parents, she pursued an advanced education at several colleges, including Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College) in Massachusetts. After graduating in 1857, she continued to study and began teaching at Vassar College in New York. Morrison thrived in a college atmosphere. Reflecting on her Holyoke and Vassar professors, Morrison wrote that “their wide knowledge of Latin and Greek, and in the sciences, were eye and heart openers to such as thirsted for fuller draughts of knowledge.”[2] Over the following years, she served on the faculty of several colleges, including Glendale Female College and the Western Female Seminary, both in Ohio.[3]

Morrison also wrote that as a young woman, she was aware of the work of Lucy Stone and Susan B. Anthony, “but their position was too peculiar, too audacious to be received wholy [sic] by such as had no courage and a rather sensitive imagination respecting mobs, sneers, hisses, mud-slinging and rotten eggs.” Instead, Morrison held a “secret respect” for these suffragists, as well as a desire to strengthen her nerve and awaken her conscience. Her fears of a negative response were she to enter the battle for women’s rights would be substantiated.[5]

Morrison had completed her advanced education and served as a professor at several colleges, but by the 1860s, she was again living back home because of the limited occupational opportunities available to a highly-educated woman. At this time, the Indiana University Board of Trustees had been debating the admission of women. Sarah Morrison’s father John, who was the State Treasurer as well as a former IU board president, advocated for women’s admission and persuaded his daughter to petition the board for entrance. Morrison had to be convinced. She was not an eager, young girl just out of primary school, hoping to expand her knowledge. She was a 34-year-old scholar and teacher with a lifetime of education and an advanced knowledge of ancient languages. She had little desire to be the first woman student at IU, or the subject of controversy, but she conceded for the larger good – and a five dollar bribe. Morrison wrote:

Father . . . said to me that he thought the time was about ripe for the admission of women; and that if I would prepare an appeal to that effect he would present it, and to show his interest would give me Five Dollars.[6]

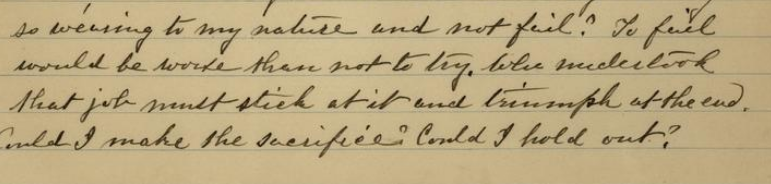

She wrote that she was tired of going to school, but she was more tired of the old arguments about why women shouldn’t attend a university. According to Morrison, these arguments included the idea that the “Female Colleges” were good enough for young women, there were too many “risks” in women and men attending the same schools, and male students and professors should be saved from the “embarrassment – yea scandal” of women’s presence. Morrison looked at the IU catalogue and determined she could complete the four-year course in two. She was worried though. “To fail would be worse than not to try,” she wrote. The first female student at IU would be representing her entire gender to the masses, not all who believed she deserved to be there.[8]

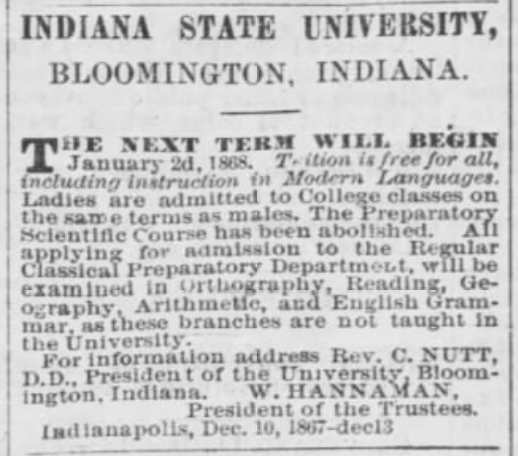

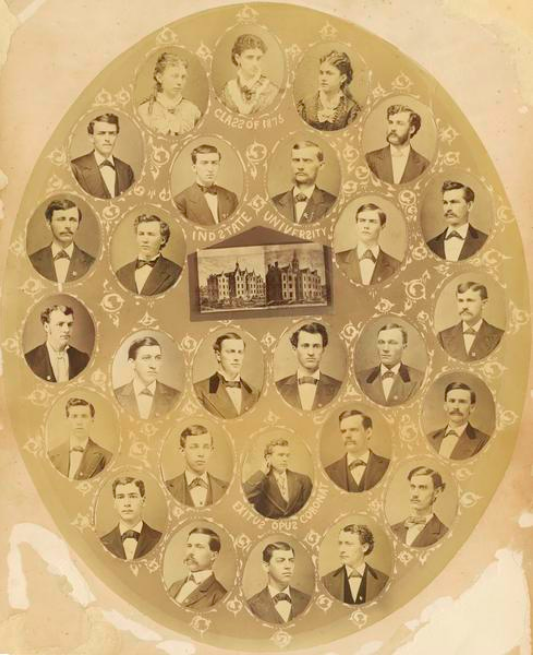

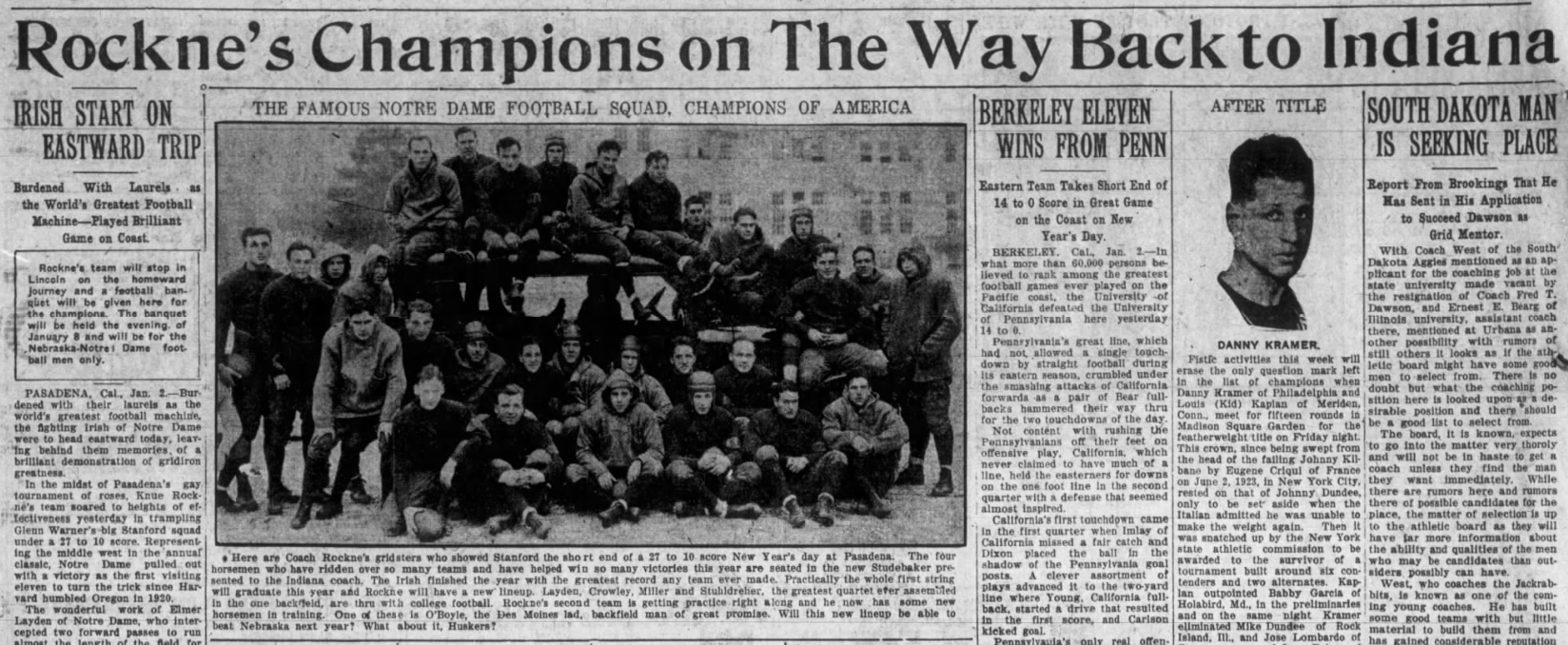

Morrison entered Indiana University along with three hundred young men in the fall of 1867.[9] She wore a large sun hat to protect herself “from six hundred eyes” trying to cast “a sly glance” at the school’s first female student. She soared through her Latin and Greek classes and by the second semester of her first year she became a sophomore.[10] More importantly, during that spring semester of 1868, a dozen women followed Morrison’s lead, entering Indiana University as freshmen students. In a powerful contemporary photograph, Morrison is seated front and center, surrounded by the women who followed in her wake.[11]

The next year, Morrison continued her accelerated course of study, beginning the fall semester as a junior and becoming a senior spring semester. She wrote that she could probably have skipped Latin “if I had chosen to make a point of it,” but instead “read more than really required” so no one could claim that she would “lower the standard.” At one point during her first semester, the students could choose to write an essay or make an oral argument for a final exam. The professor assumed Morrison would prefer an essay so as not to speak in front of an audience of male students. She responded simply, “why?” Her second semester, a professor discouraged her from making her “declamation” at examinations, which would be attended by the general public. Morrison told him that she had appealed to the Board, not him, for her position and he could not stop her from making her declamation in the same manner as her male colleagues. Yet another professor acknowledged her ability for public speaking, but discouraged her from engaging in an exercise where she would debate her male colleagues. She again responded, “why?” and entered the debate. Finally, before graduation, a professor encouraged her to submit an essay and not to speak at commencement. She again asked him simply, but pointedly, “why?” Morrison explained:

‘Why?’ became my one and only, but effective ammunition when approach to the ‘Woman question,’ was bold enough to lift its head.[12]

By this, Morrison meant that when faced with the question of whether her gender should prevent her from equal participation at the university, she simply asked the professor “why” because her continued success and proficiency left no answer that could be based on anything but gender discrimination.

Similarly, when she received a “slighting remark” from a fellow student, whom she described sarcastically as “a rather superior young gentleman,” she “lost her temper” but managed to bite her tongue. She chose not to retort, explaining: “It was probably intended as a test. If I was mad internally, I could not suffer my cause to suffer.” Instead, she chose to focus her efforts on her commencement address. She knew many had low expectations for her performance. She wrote:

To have a performance at Commencement that would pass a general critical public, was an undertaking, indeed for me. I could not come down to their notions, could I lift them up to mine?[13]

Morrison became the first woman to graduate Indiana University in the spring of 1869 with a Bachelor of Arts degree.[14] Indiana newspapers reported that Morrison “graduated in the Classical course with great credit to herself, delivering in a splendid manner a very fine oration.”[15] Newspapers across the country picked up the story, reporting on “the first female graduate of Indiana State University.”[16] She demonstrated that there was indeed no reason “why?” a woman couldn’t succeed at Indiana University.

Like the stories of other women trailblazers, the moment where the glass ceiling shattered, is often the point where Morrison’s story ends for historians. But what was it like for Morrison and other women once they became the first and only woman in their place of employment? What did it feel like to be the only woman in the lecture hall, laboratory, or operating theater? Of course experiences vary, but all faced some level of discrimination, opposition, or misogyny. Morrison faced all of these, delivered with a maliciousness some might find surprising for a genteel, academic setting.

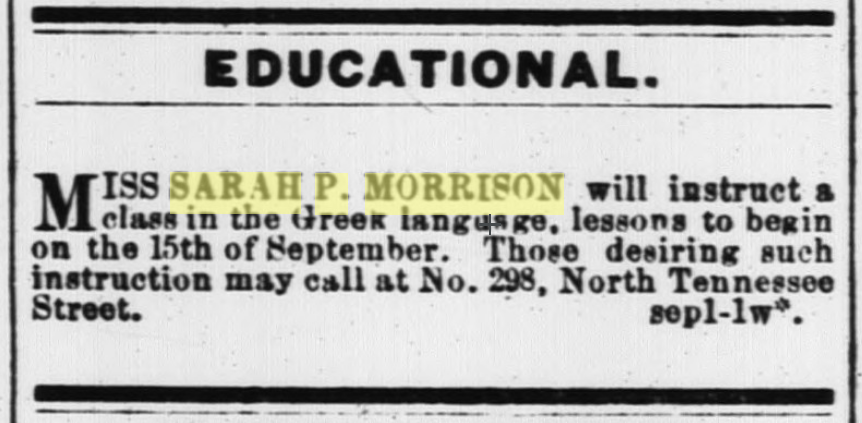

Several of her male students refused to recite to her, recitation being the manner in which students orally showed their comprehension of the class material. By refusing to recite, they were showing that they refused to recognize her authority. They deemed that, as a woman, she was unqualified to teach them as men. Despite her years of schooling, mastery of several languages, experience teaching, advanced degrees, and praise from professors, these undergraduate students claimed that she was undeserving of their respect because of her gender. Newspapers in Indiana and then across the country, picked up the story. Taking an amused tone over her “awkward predicament,” newspapers reported on her appointment to IU faculty and the student discrimination in the same article.[23] The Chicago Tribune reported:

Miss Sarah P. Morrison, daughter of the President of the Board to Trustees and adjutant Professor of English Literature in the State University, has been struck against by a portion of the students, who refuse to recite to her. No adjustment of the difficulty has yet been made.[24]

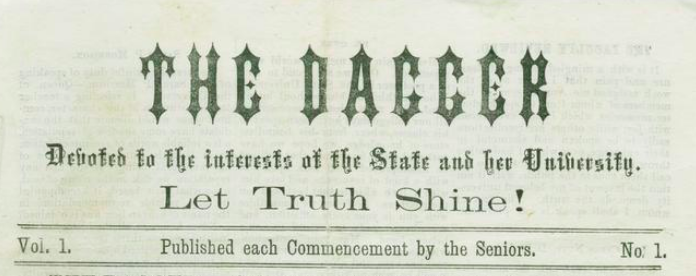

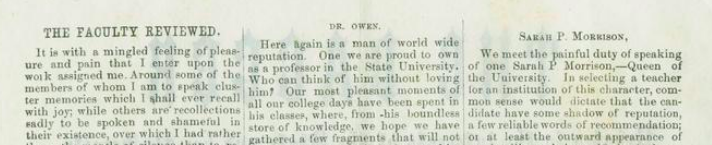

Not content to demonstrate their disrespect for their professor through silence, some of the students in the fraternity Beta Theta Pi published an article slandering her character and qualifications. At the end of the school year, the fraternity published an issue of their newspaper the Dagger, which Indiana University Archives referred to as “the 19th century version of Rate My Professor.”[25] For Morrison, who had long moderated her work for women’s advancement for fear of backlash, the 1875 issue would have been humiliating and devastating.

Sarcastically referring to Morrison as “the Queen of the University,” these male students published a horribly sexist, misogynistic criticism of Morrison’s teaching and intelligence. They claimed she had no right to her professorship because she lacked even “some shadow of reputation, a few reliable words of recommendation; or at least the outward appearance of an intelligent being.” They claimed she barely taught any classes, was “pinned to the coat tail of our faculty,” and got paid to do “nothing whatever.” They wrote, “Never before in all the history of the institution, has there been so gross and imposition practiced upon the taxpayers of Indiana.” They continued with base name calling, referring to her in turn as “impudent,” lacking “all common sense,” “idiotic,” and an “uneducated ape.” The students claimed:

Petitions for her removal have been thrust in the faces of both her and her father. But shame has lost its sting upon this impudent creature, dead to the pointing finger of withering scorn.[26]

They wrote that “their diplomas are disgraced by her contemptible name” and that the senior class would be marking her name out on their diplomas. They concluded the article:

We close with the warning to our idiotic subject. O! Sallie that you may not make a consummate ass of yourself, hast-to your mothers [sic] breast, sieze [sic] the nipple of advice and fill your old wrinkled carcass with the milk of common sense.[27]

The condescension and entitlement mixed with sexism is hard to read, especially knowing how qualified and intelligent Morrison was, but also how timidly she accepted the responsibilities that came with her groundbreaking position. Perhaps one element makes this misogynistic slander slightly bearable today: unintended humor. In short, the young men were terrible writers. Ironically, these students who claimed that Morrison did not posses the intelligence to be their teacher, populated their vicious article with spelling and grammar errors. Undoubtedly, they should have listened to what she could have taught them.

It would be much more satisfying to report that Morrison persevered in the face of this misogyny and went on to teach for many more years, but not all stories of women who furthered the fight for equality end with professional success and empowerment. Morrison left the university and the profession that she loved after the 1874-75 school year. She instead became an active advocate for the temperance movement, traveling throughout the country, including into Indian territory, and spoke at the national level.[28] She became a leader within the Society of Friends, speaking at state meetings.[29] And she penned poems and family histories.[30]

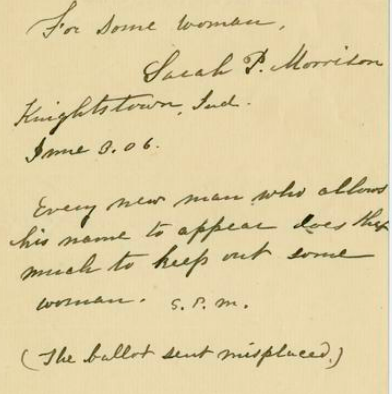

Though she never returned to teach at IU, she stayed involved with the university. She spoke at alumni events and commencements and wrote regular letters to the administration. Through these letters, she advocated for placing women on the Board of Trustees and the Board of Visitors, as well as hiring women professors. These letters show her finding strength in herself in demanding greater opportunities for women. For example, in 1906, she submitted her vote to the Board of Trustees “For Some Woman” and wrote on her ballot: “Every new man who allows his name to appear does that much to keep out some woman.”[31]

Though Miss Morrison is 75 years of age, she is as sprightly of body and mind, apparently, as she was when a student at the university nearly fifty years ago. She has never lost her interest in the classics nor in poetry.[32]

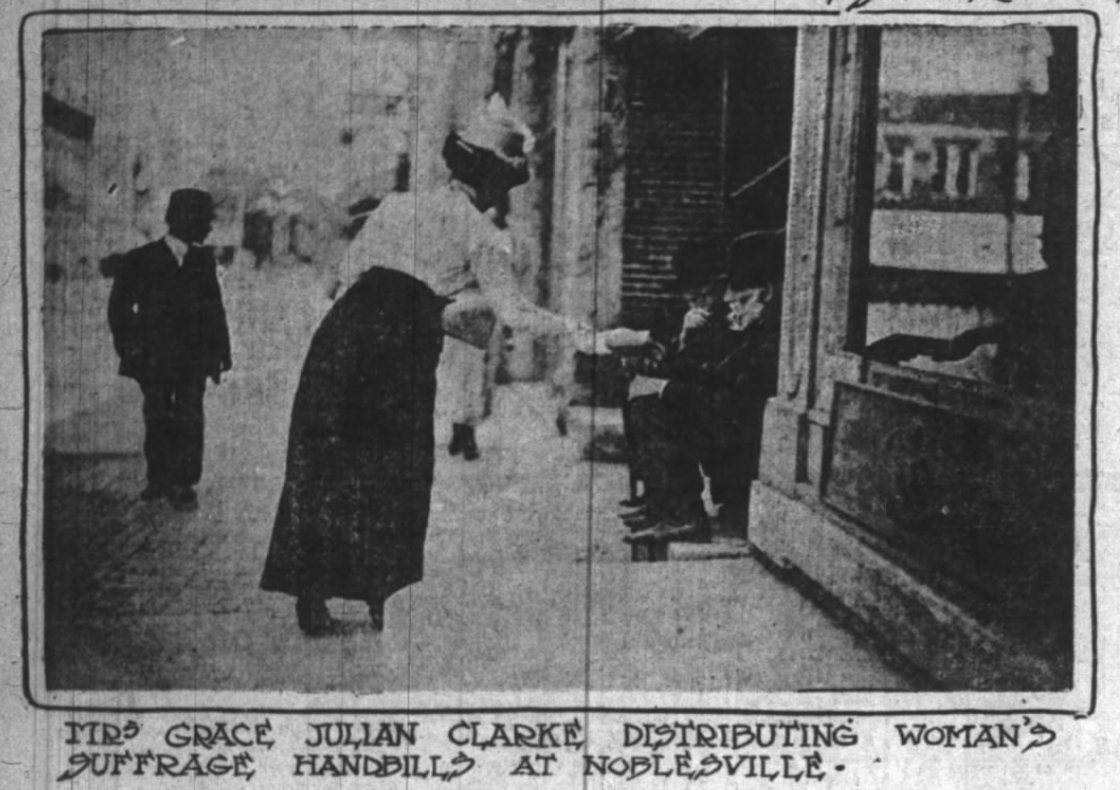

She must have continued to impress IU staff and administration because she delivered the alumni address at the 1909 commencement.[33] Morrison also continued to write to the IU administration in her later years. In 1911, she advised the university’s president and the Board of Trustees on filling a teaching position upon the death of a female professor. It’s likely that this advice was unsolicited, but she chose strong and clear words. She stated that the woman the Board chose to fill the vacant position should possess “very decided views respecting the equal [underline] privilege granted the young women of our University, and accepting suffrage for women as a matter of course.”[34] Before her death in 1916, Morrison found the courage to outwardly support women’s suffrage, something she had feared as a younger women.

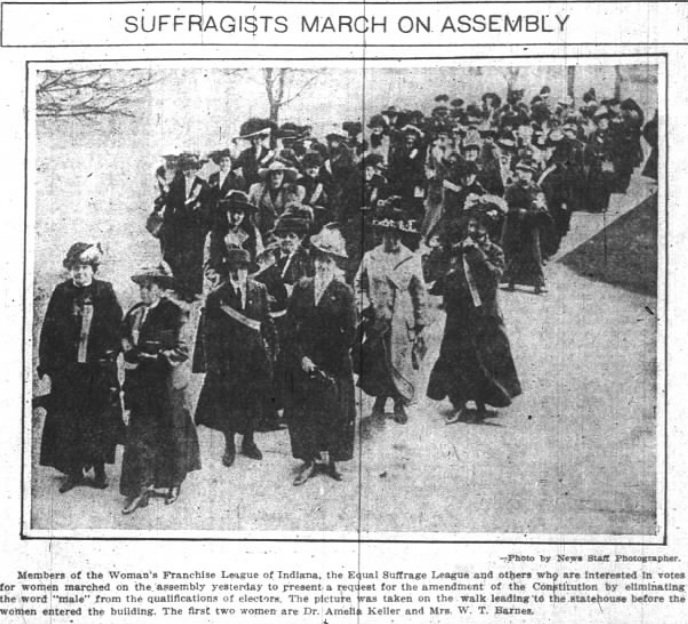

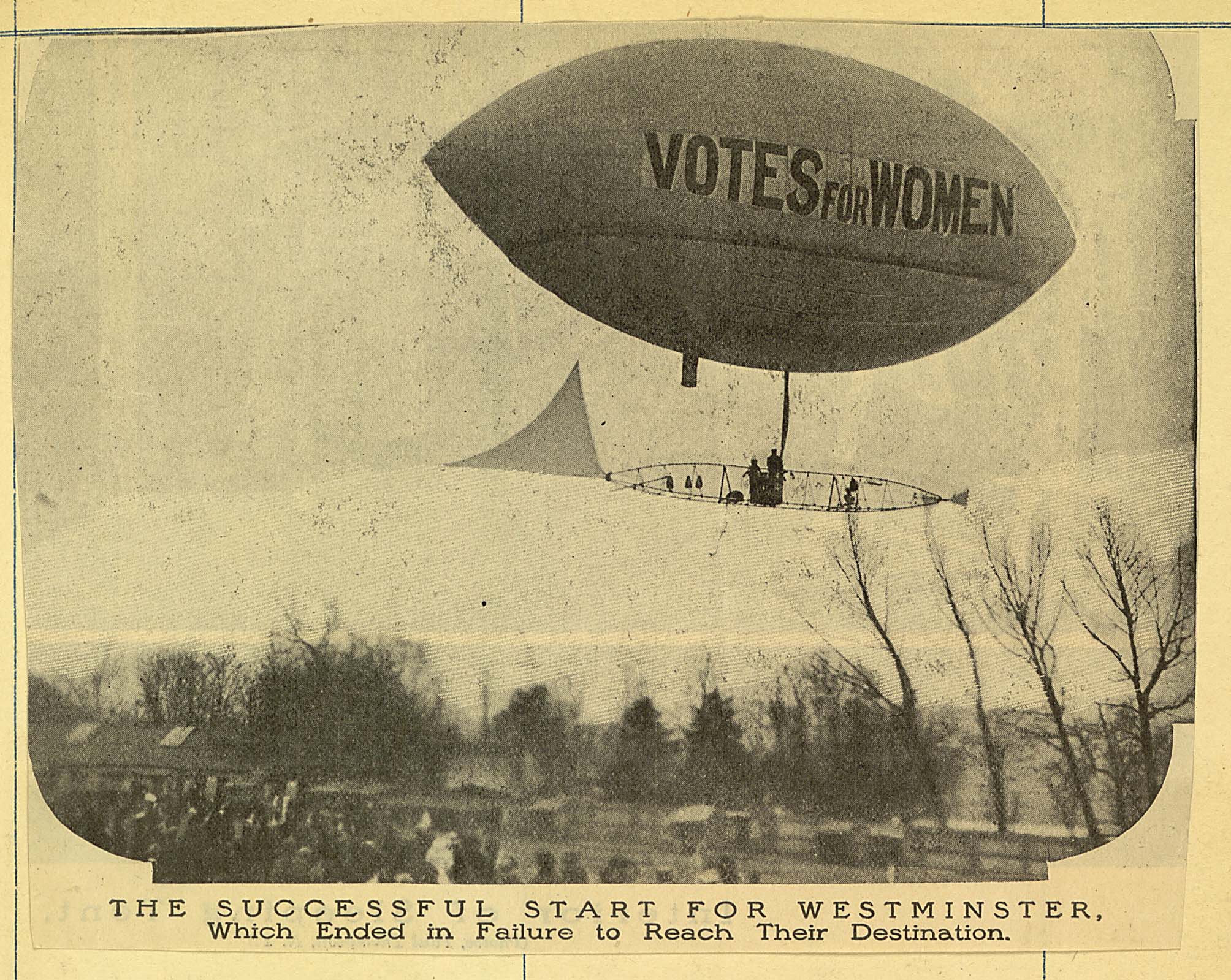

This year, while commemorating the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, historians have enthusiastically shared stories of bold suffragists who marched in the streets and spoke passionately to large crowds – those women who stood unafraid before the Indiana Supreme Court or the Indiana General Assembly to demand their rights. But not all of the women who blazed the path toward equality loudly beat the drums of reform. Morrison shied from controversy and rightfully feared backlash from entering previously all-male spaces, but she ventured forward anyway. This is the very definition of courage – to persevere in the face of fear. While sometimes reluctant, she made important gains for women at Indiana University. Hers was the foot in the door, wedging it open for other women to follow her. And they did. Sarah Parke Morrison should be remembered not only for her “firsts,” but for her selflessness, determination, and quiet audacity.

Notes:

[1] 1850 U.S. Federal Census, Washington Township, Washington County, Indiana, September 20, 1850, roll 179, page 37 (338A), line 35, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; “Raysville Monthly Meeting, Henry County,” 1876, Earlham College, Richmond, Indiana Minutes, Indiana Yearly Meeting Minutes, accessed AncestryLibrary; “Indiana University,” [Alumni Form], 1887, Sarah Parke Morrison Papers, Indiana University Archives, submitted by marker applicant.; Indiana State Board of Health, “Certificate of Death,” (Sarah Parke Morrison), July 9, 1919, Roll 13, page 532, Indiana Archives and Records Administration, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; “Biographical Note,” Sarah Parke Morrison Papers, Archives at Indiana University. The quoted text comes from the “Biographical Note” written by the Archives at Indiana University.

[2] Annual Catalogues of the Teachers and Pupils of the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary from 1847-1857 (Northampton: Hopkins, Bridgman & Co., n.d.), 44, accessed HathiTrust.; “Indiana University,” [Alumni Form], 1887, Sarah Parke Morrison Papers, Indiana University Archives, copy available in IHB marker file.; Indiana University, Arbutus [yearbook], 1896 (Chicago: A.L. Swift & Co. College Publications, 1896), accessed HathiTrust.

[3] Advertisement, “Glendale Female College,” Washington Democrat (Salem, Indiana), February 24, 1859, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.; Memorial: Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of the Western Female Seminary, Oxford, Ohio, 1880 (Indianapolis: Carlon & Hollenbeck, Printers and Binders, 1881), 208, accessed GoogleBooks.

[4] Fannie (Morrison), “Lines to Robert Dale Owen,” Indiana State Sentinel, March 27, 1851, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[5] Sarah Parke Morrison, “My Experience at State University,” 1911, Box 1, Series: Writings, Sarah Parke Morrison Papers, Archives at Indiana University.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Advertisement, “Indiana State University,” Evansville Daily Journal, December 19, 1867, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[8] Morrison, “My Experience at State University.”

[9] Annual Report of Indiana University, Including the Catalogue for the Academical Year, 1867 (Indianapolis: Samuel M. Douglass, State Printer, 1868), Indiana State Library.

[10] Morrison, “My Experience at State University.”

[11] Annual Report of Indiana University, Including the Catalogue for the Academical Year, 1867 (Indianapolis: Samuel M. Douglass, State Printer, 1868), Indiana State Library.; “Women Students,” accessed Indiana University Archives Exhibits.

[12] Morrison, “My Experience at State University.”

[13] Ibid.

[14] Annual Report of Indiana University, Including the Catalogue for the Academical Year, 1868-69 (Indianapolis: Samuel M. Douglass, State Printer, 1869), Indiana State Library.

[15] “Commencement at the State University,” (Greencastle) Putnam Republican Banner, July 8, 1869, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[16] “Digest of Latest News,” Galveston Daily News, July 24, 1869, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.; Fair Haven (Vermont), July 31, 1869, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[17] Advertisement, “Educational,” Indianapolis Daily Sentinel, September 3, 1869, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[18] “Normal School,” Terre Haute Daily Gazette, July 20, 1870, 4, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[19] “All Sorts and Sizes,” Bangor Daily Whig and Courier (Bangor, Maine) July 30, 1872, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.; Freeman’s Journal (Dublin, Ireland), September 11, 1872, 8, accessed Newspapers.com.

[20] Annual Report of Indiana University, Including the Catalogue for the Academical Year, 1872-73 (Indianapolis: Samuel M. Douglass, State Printer, 1873), Indiana State Library.

[21] Annual Report of Indiana University, Including the Catalogue for the Academical Year, 1873-74 (Indianapolis: Samuel M. Douglass, State Printer, 1874), Indiana State Library.

[22] Annual Report of Indiana University, Including the Catalogue for the Academical Year, 1874-75 (Indianapolis: Samuel M. Douglass, State Printer, 1875), Indiana State Library.

[23] Chicago Weekly Post and Mail, November 26, 1874, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[24] “Indiana,” Chicago Tribune, November 19, 1874, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Former Trustees,” Indiana University Board of Trustees, https://trustees.iu.edu/the-trustees/former-trustees.html.

While Sarah Morrison’s Father John I. Morrison was an IU Board member 1874-75, he was not the president.

[25] “The Dagger: The 19th Century Version of Rate My Professor,” January 26, 2016, accessed Indiana University Archives.

[26] “Faculty Reviewed: Sarah P. Morrison,” The Dagger, 1875, 2, Box OS3, accessed Archives Online at Indiana University.

[27] Ibid.

[28] “Woman’s Temperance Union,” Vermont Chronicle (Bellows Falls) November 15, 1879, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Noble Women,” Washington Evening Critic (Washington, D.C.), October 29, 1881, 1, Newspapers.com.; “Work for Women,” Indianapolis Journal, January 30, 1886, 8, accessed Chronicling America, Library of Congress.; Izumi Ishi, Bad Fruits of the Civilized Tree: Alcohol & the Sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 136, accessed Google Books.

[29] “The Quakers,” Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1877, 8, accessed Newspapers.com.; “The Yearly Meeting,” Richmond Item, October 1, 1892, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.; “At Plainfield,” (Chicago) Inter Ocean, September 17, 1894, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

[30] “Current Literature,” (Chicago) Inter Ocean, June 18, 1892, 12, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Literary Notes,” Friends Intelligencer and Journal 60 (Philadelphia: Friends Intelligencer Association, 1903), 187, accessed Google Books.

[31] Sarah Parke Morrison to “Alma Mater,” January 16, 1905, Sarah Parke Morrison Papers, Box 1, Correspondence, Archives at Indiana University.; Sarah Parke Morrison to William L. Bryan, February 22, 1905, Sarah Parke Morrison Papers, Box 1, Correspondence, Archives at Indiana University.; Sarah Parke Morrison to William L. Bryan, December 4, 1905, Sarah Parke Morrison Papers, Box 1, Correspondence, Archives at Indiana University.; Sarah Parke Morrison to Isaac Jenkinson, January 19, 1906, Sarah Parke Morrison Papers, Box 1, Correspondence, Archives at Indiana University.

[32] “Still A Student at 75,” New York Times, June 28, 1908, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[33] “Alumni Day at the State University,” Indianapolis News, June 22, 1909, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Indiana College News,” Indianapolis Star, June 17, 1909, 9, accessed Newspapers.com.

[34] Sarah Parke Morrison to Indiana University President and Board, March 7, 1911, Sarah Parke Morrison Papers, Box 1, Correspondence, Archives at Indiana University.

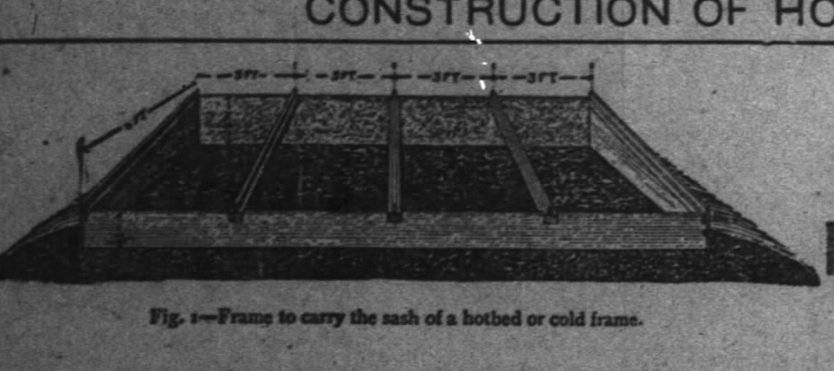

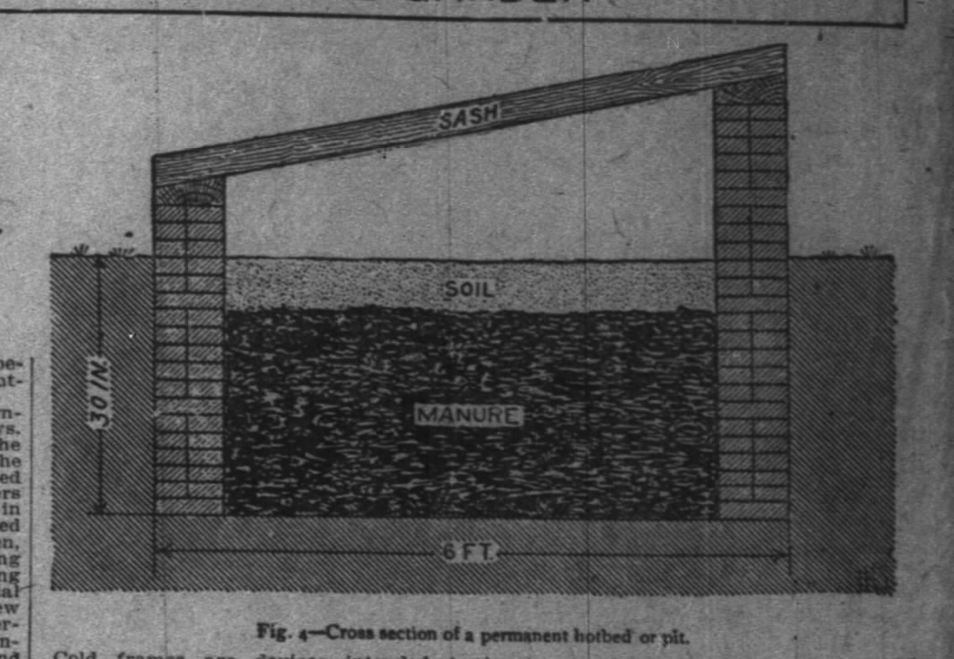

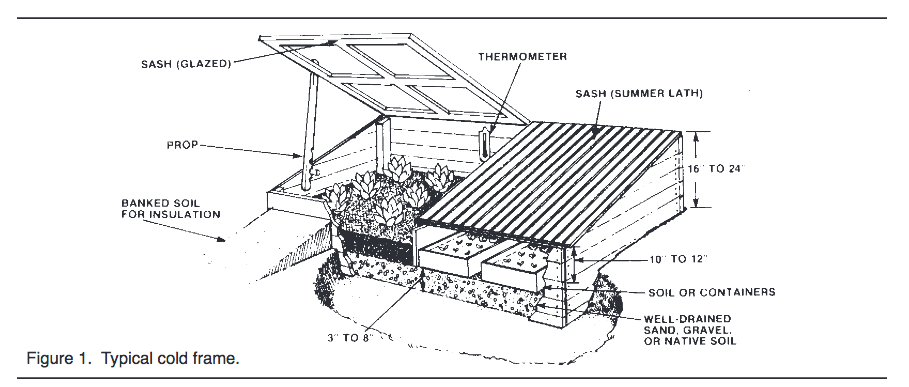

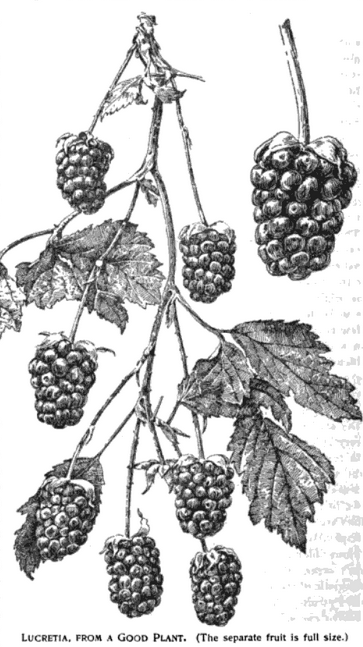

Many people are looking for ways to channel the anxiety of our current crisis into something healthy and productive. For those of us with green thumbs, this has meant more time in the garden. And there is no better place for us to get some sage advice than from those Hoosier gardeners who came before us. Luckily, some of them shared their wisdom in an early-twentieth century column in the Indianapolis News titled “Of Interest to Farmer and Gardner.”

Many people are looking for ways to channel the anxiety of our current crisis into something healthy and productive. For those of us with green thumbs, this has meant more time in the garden. And there is no better place for us to get some sage advice than from those Hoosier gardeners who came before us. Luckily, some of them shared their wisdom in an early-twentieth century column in the Indianapolis News titled “Of Interest to Farmer and Gardner.”

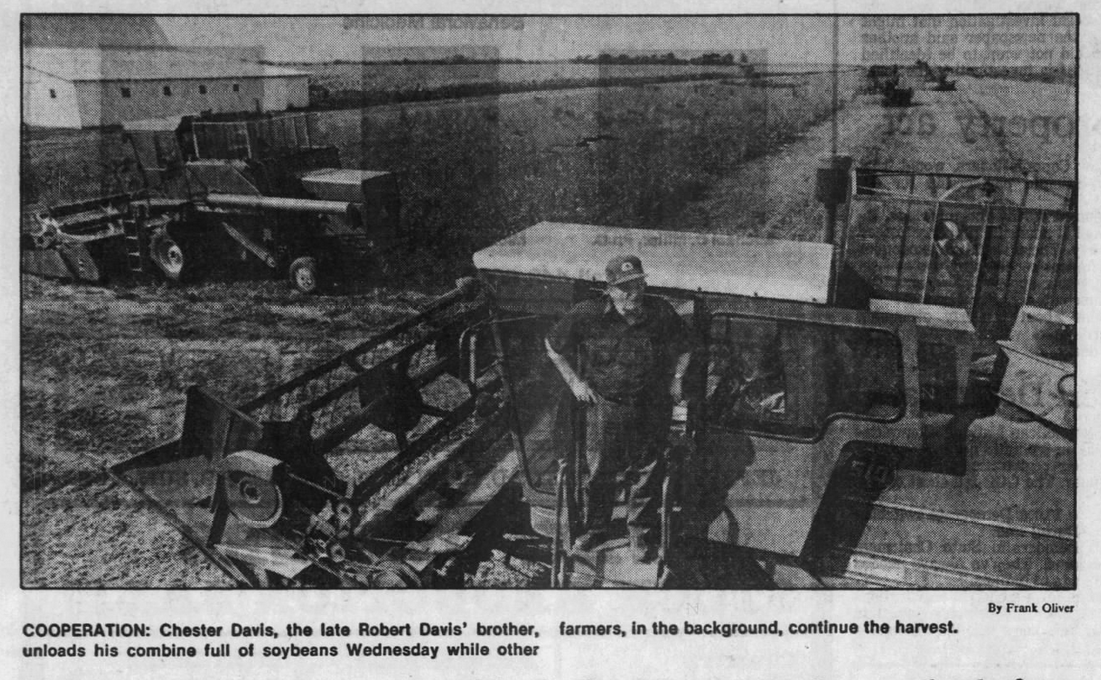

One of the farmers, Robert Akers, told the local newspaper simply, “This is just the way the community works.” The neighbor who organized the harvest, Ralph Reed, echoed the sentiment, stating: “It’s just a job that has to be done.” Reed explained that this community effort was their “own kind of insurance.” Robert’s brother Clive teared up when he told the local reporter:

One of the farmers, Robert Akers, told the local newspaper simply, “This is just the way the community works.” The neighbor who organized the harvest, Ralph Reed, echoed the sentiment, stating: “It’s just a job that has to be done.” Reed explained that this community effort was their “own kind of insurance.” Robert’s brother Clive teared up when he told the local reporter:

Like a lot of people, the historians at IHB are working from home. We’re feeling very lucky to be healthy and employed, as we know not everyone is so fortunate. As usual, we’re trying to find historical stories that will be of interest, and hopefully useful, to our fellow Hoosiers in these strange times in which we find ourselves.

Like a lot of people, the historians at IHB are working from home. We’re feeling very lucky to be healthy and employed, as we know not everyone is so fortunate. As usual, we’re trying to find historical stories that will be of interest, and hopefully useful, to our fellow Hoosiers in these strange times in which we find ourselves.