This blog post has been adapted from a paper submission for the 2019 Bennett-Tinsley Undergraduate History Research and Writing Competition. For further analysis of Camp Morton and Civil War politics, see Dr. James Fuller’s Oliver P. Morton and Civil War Politics in Indiana.

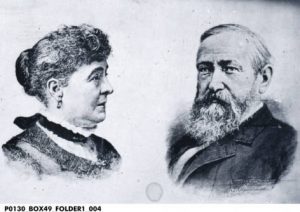

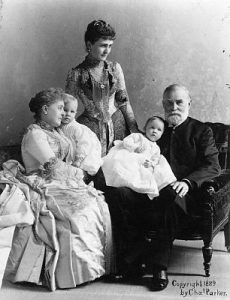

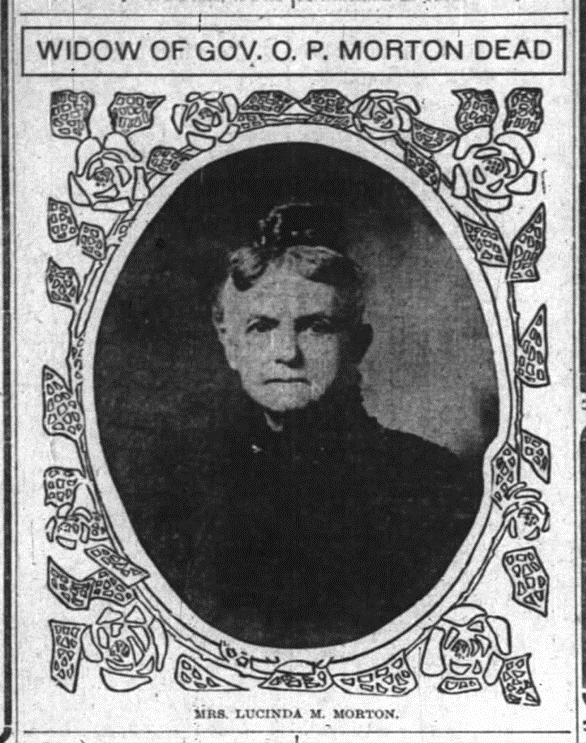

History has a tendency to exclude women who were just as imperative—if not more so—than their male counterparts, like Edna Stillwell, the wife of Red Skelton, and Susan Wallace, the wife of Lew Wallace. This is the case with Lucinda Burbank Morton, a woman of “rare intelligence and refinement,” known most commonly as the wife of Oliver P. Morton, the 14th Governor of Indiana. Yet she served an influential role in the Midwest abolition movement and relief efforts for the American Civil War, especially in her work with the Ladies Patriotic Association and the Indiana division of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. She worked diligently to help develop the young City of Indianapolis and push Indiana through its early years of statehood. Despite her tremendous contributions, Lucinda’s place in history is mostly marked by her marriage to Governor Morton. Although the role of First Lady is significant, what she gave to her state and, consequently, country, goes beyond this title.

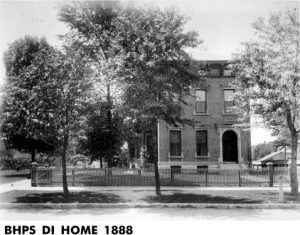

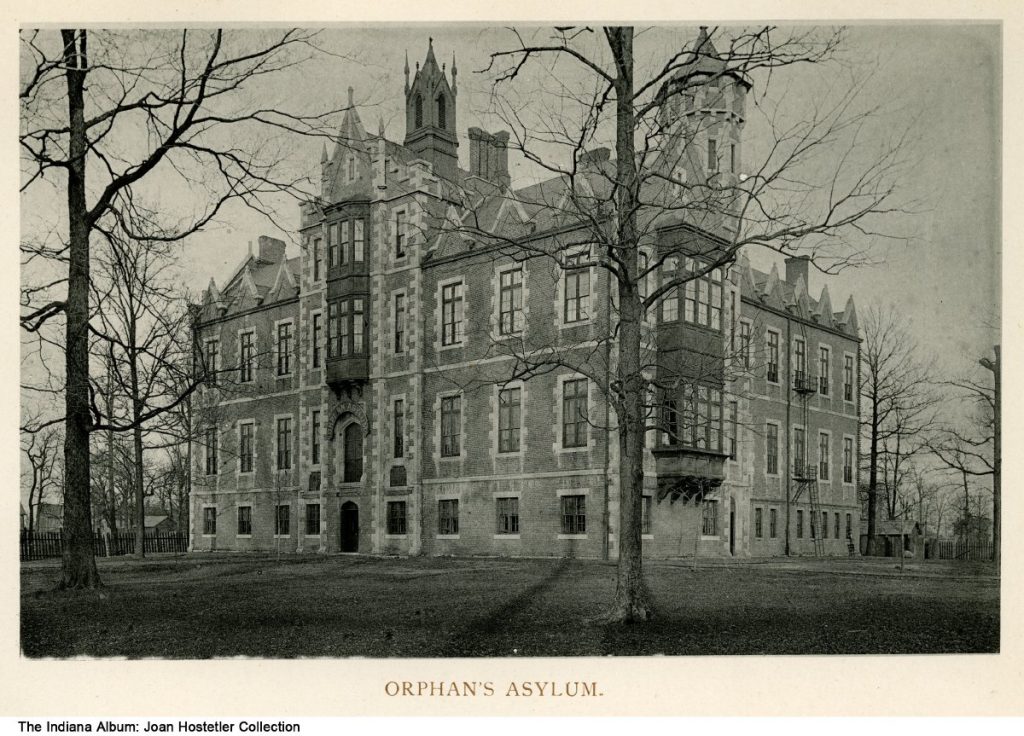

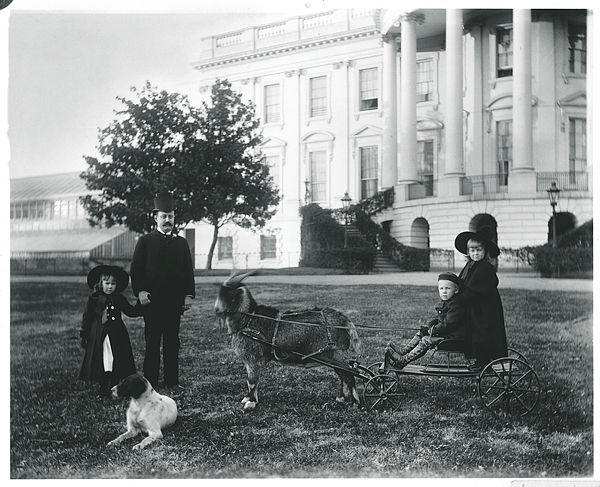

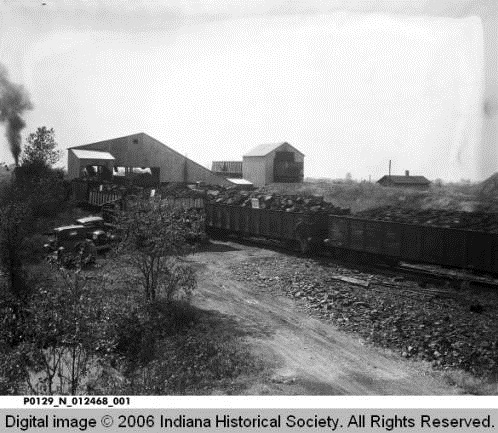

The moment the news of Fort Sumter reached Indianapolis, Governor Morton delegated Adjutant General, Lew Wallace, to oversee the creation of a camp for mustering and training Union volunteers. Wallace turned the fairgrounds in Indianapolis into “Camp Morton,” named after the wartime governor himself. In 1862, it was converted into a POW camp. The North and South were warring after decades of unrelenting tension over slavery, and, as a central location, Indianapolis would need to be ready for enemies captured by Union forces. Even though Confederate troops were going to be imprisoned here, Lucinda saw soldiers as people first, no matter their affiliation. She realized that it would take an army to, quite literally, feed an army, and quickly took over the role of organizing and managing necessities for Camp Morton. Headed by Lucinda, the Ladies Patriotic Association (LPA), thus, began providing for those imprisoned in the camp in the latter half of 1862.

The LPA consisted of Hoosier women of political and/or social prominence. The organization served as one of the first major philanthropic endeavors of Lucinda Burbank Morton, perhaps the most ambitious effort yet. The women of the association often met in the Governor’s Mansion to strategize and, depending on what the Camp Morton prisoners needed at that time, collect and craft donations for the camp. For example, at one particular meeting, the Ladies sewed and knitted over $200 worth of flannel hats, scarves, and mittens for Confederate prisoners in preparation for the upcoming harsh, Indiana winter. The Ladies hand-stitched so many pieces of clothing that Governor Morton had to step in and politely decline any more donations of the sort for the time being.

As Spring transitioned into Summer the following year, an outbreak of measles plagued the camp. Lucinda Burbank Morton and her fellow Ladies banded together to help replace blankets, pillows, and towels. Their polite prodding of Hoosiers across the state invoked donations of salt, pork, beer, candles, soap, and dried fruits. In the early days of Camp Morton, jokes circulated that the prisoners had to be reminded that they were, indeed, still prisoners because of how comfortably they lived as a result of the generous donations from the Ladies Patriotic Association.

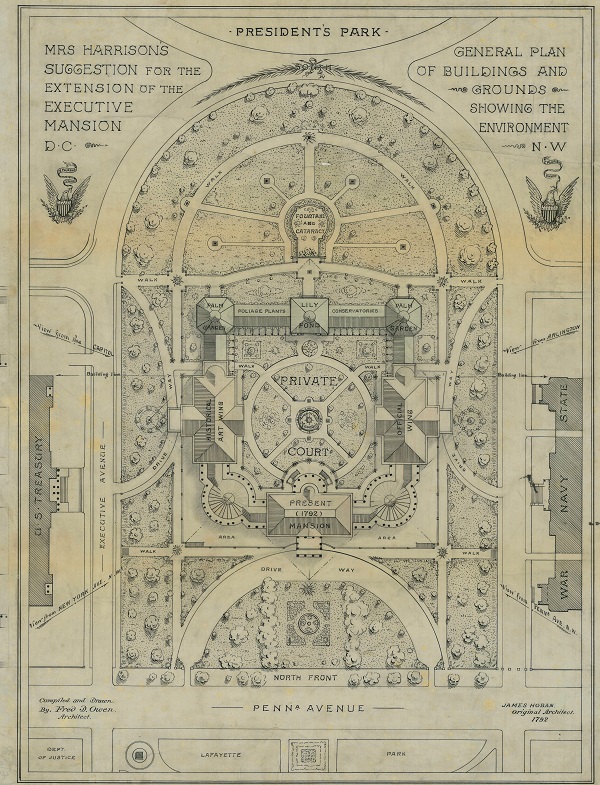

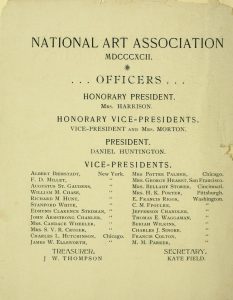

Meanwhile, President Abraham Lincoln continued to seek relief for Army camps from across the Union. A wave of patriotism swept over the daughters, wives, and mothers of Union soldiers as more and more troops were sent off to war against the Confederacy. On April 25, 1861, these women met in New York to better organize the relief efforts of the Union. The roots of the Women’s Central Association of Relief (WCAR) were established at this meeting. Members learned about the WCAR through friends and family members, and others belonged to the same sewing circle or taught alongside each other at primary schools. They all had the same goal in mind—to contribute as much, if not more, to the war effort as their male counterparts.

U.S. legislators responded to the needs identified by the Women’s Central Association of Relief with the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC). As a private relief agency, the USSC supported Union soldiers during the American Civil War. It operated across the North, raising nearly $25 million in supplies and monetary funds to help support Union forces during the war. The government could only do so much in providing for its troops; the USSC allowed concerned civilians to make up for any administrative shortcomings.

With the establishment of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, individual states began to create their own divisions to meet the need for infantry relief. Governor Morton ordered the Indiana division of the Sanitary Commission to be constructed in 1862. The commission helped to balance out the hardships of war for many Hoosier troops. The Indiana division spoke to the idea of Hoosier Hospitality, providing rather comfortable amenities and ample resources for POWs.

The Indiana Sanitary Commission officially began implementing aid and relief after the Battle of Fort Donaldson in February of 1862. From that year to December of 1864, the Indiana homefront put forth approximately $97,000 in cash contributions. Over $300,000 worth of goods and supplies were donated, totaling nearly $469,000 in overall aid. The Office of the Indiana Sanitary Commission wrote of these contributions in a report to the governor:

The people of Indiana read in this report not of what we [the government], but they have done. We point to the commission as work of their hands, assured that the increasing demands steadily made upon it will be abundantly supplied by the same generous hearts to which it owes its origins and growth, all of which is respectfully submitted.

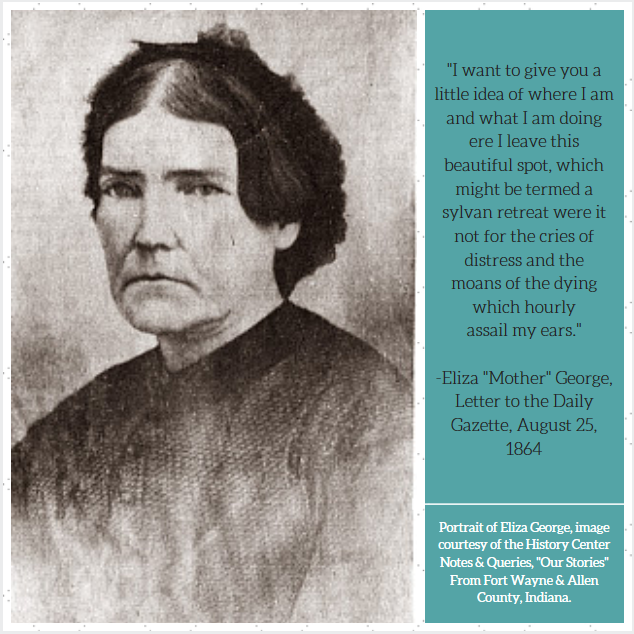

The citizens of Indiana and their government, alike, were keenly aware of the contributions they were making to the war effort. The report to Governor Morton also included lists of influential members of the Commission, including special sanitary agents, collection agents, special surgeons, and female nurses. Of these notable entries, nurses accounted for the majority of names compiled. Twenty-five of them operated from Indiana to Nashville, Tennessee and beyond for the Union Army. One such woman, Mrs. E. E. George worked alongside General William Tecumseh Sherman and his troops during the March to the Sea. She worked chiefly with the 15th Army Corps Hospital from Indiana to Atlanta; her fellow male soldiers later described Mrs. George as being “always on duty, a mother to all, and universally beloved, as an earnest, useful Christian Lady.”

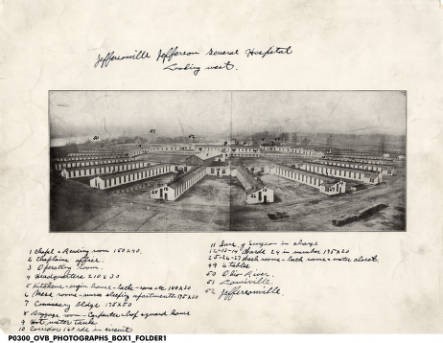

Indiana’s Superintendent of Female Nurses, Miss C. Annette Buckel, brought over thirty-five nurses to work in Jeffersonville, Indiana, and Louisville, Kentucky hospitals. Her demeanor, dedication, and administrative qualities were spoken of in the Commission Report to the Governor, citing that Buckel deserves “the utmost praise.” Additionally, Hoosier nurses Hannah Powell and Arsinoe Martin of Goshen, Indiana gave their lives serving in the Union Hospital of Memphis, Tennessee in 1863. The women known for their humanitarian contributions and patriotic sacrifices were pronounced as:

Highly valued in the family and in society, they were not less loved and appreciated in their patient unobtrusive usefulness among the brave men, for whose service, in sickness and wounds, they had sacrificed so much. Lives so occupied, accord the highest assurance of peaceful and happy death; and they died triumphing in the faith of their Redeemer, exulting and grateful that they had devoted themselves to their suffering countrymen. Their memories, precious to every generous soul, will be long cherished by many a brave man and their example of self-denial and patriotic love and kindness, will be echoed in the lives of others who shall tread the same path.

Lovina McCarthy Streight was another prominent woman from Indiana who served the Union during the Civil War. Her husband, Abel, was the commander of the 51st Indiana Volunteer Infantry, and when he and his troops were sent off to war, Streight and the couple’s 5-year-old son went along with the regiment. Streight nursed wounded men with dedication and compassion, earning her the title of “The Mother of the 51st.” Confederate troops captured Streight three times; wherever her husband and his men went, she went, too, right into battles deep within Southern territory. She was exchanged for Confederate Prisoners of War the first two times she was captured, but, on the third time, Streight pulled a gun out of her petticoat. She consequently escaped her captor and made her way back to her husband and son as well as the rest of the 51st Indiana Volunteer Infantry. In 1910, Streight passed away and received full military honors at her funeral in Crown Hill Cemetery which was attended by approximately 5,000 people, including 64 survivors of the 51st Volunteer Infantry.

As the Civil War progressed, Lucinda Burbank Morton stood at the center of the Hoosier state’s philanthropic relief efforts. But Governor Morton and his controversial administration placed unspoken pressure upon Lucinda to be all the more pleasant and amicable yet just as determined with her outreach endeavors. Indiana historian Kenneth Stampp described Governor Morton as:

. . . an extremely capable executive, but he [Morton] was blunt, pugnacious, ruthless, and completely lacking in a sense of humor. He refused to tolerate opposition, and he often harassed his critics to complete distraction. The men associated with him ranked only as subordinates in his entourage.

Nevertheless, Lucinda acted as a cogent leader for women not just in Indiana, but across the Union, and even opened her own home to ensure the success of such efforts. Lucinda’s work spiraled into something much bigger in terms of the health and wellness of the men fighting the war that divided her beloved country.

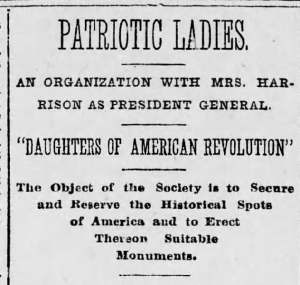

The efforts of Morton and her fellow Union women marked one of the first times in the history of the United States where women were collectively seen as more than just mothers and wives, however important such roles might be; they were strong, they were competent, and they contributed in ways that matched the efforts of Union men. However forgotten the women who helped preserve the Union might be, their dedication and tenacity shed new light on women’s organizational capabilities during the Civil War.

Sources Used:

W.R. Holloway, “Report of the Indiana Sanitary Commission Made to the Governor, January 2, 1865” (Indiana Sanitary Commission: Indianapolis, 1865).

“Proceedings of the Indiana Sanitary Convention: Held in Indianapolis, Indiana, March 2, 1864” (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Journal Co. Printers, 1864).

Jane McGrath, “How Ladies Aid Associations Worked,” How Stuff Works, June 04, 2009.

Mary Jane Meeker, “Lovina Streight Research Files,” 1988, William H. Smith Memorial Library, Indiana Historical Society.

Dawn Mitchell, “Hoosier Women Aided Civil War Soldiers,” The Indianapolis Star, March 23, 2015.

Sheila Reed, “Oliver P. Morton, Indiana’s Civil War Governor,” 2016, University of Southern Indiana, USI Publication Archives, 2016.

Kenneth M. Stampp, “Indiana Politics in the Civil War” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1978).

H. Thompson, “U.S. Sanitary Commission: 1861,” Social Welfare History Project, April 09, 2015.

Hattie L. Winslow, “Camp Morton,” Butler University Digital Commons, April 12, 2011.