On February 5, 1970, the Franklin Daily Journal in Franklin, Indiana proclaimed air pollution the “Disease of the Seventies.” It predicted that “gas masks, domed cities, special contact lenses to prevent burned eyes” would become “standard equipment if life is to exist” by 2000, unless action against widespread air pollution was taken soon.

The Daily Journal’s predictions were not off mark. Dense smog filled with toxic pollutants had already killed and sickened thousands of people in Donora, Pennsylvania in 1948, in London in 1952, and New York City in 1966. By the late 1960s, this type of deadly smog had begun to appear in nearly every metropolitan area in the US.

However, it’s now 2017, no gas masks, domed cities, or protective eye wear needed. Why? You can thank Hoosier women, who fought for air pollution control measures since the 1910s.

Women first entered the fight against coal to combat air pollution. When burned, coal releases a significant amount of smoke and soot. Londoners began burning coal for fuel as early as the 1200s. Virtually every Londoner relied on coal for fuel and heat by the 1600s as England’s forests became depleted. As industries and factories powered by coal emerged across England during the Industrial Revolution in the 17th and 18th centuries, many British cities developed air pollution problems. By 1800, a chronic cloud of smoke enveloped London. Soot and smoke dusted the streets, ruined clothing, and corroded buildings.

Major American cities did not escape the smoky air that plagued the Brits. European settlers cleared much of America’s forests for firewood, construction materials, and to make room for crops and cities. As the Industrial Revolution began on the East Coast at the end of the 18th century, industries, homes, and businesses began to rely on coal for heat and power. Dirty air followed throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Dark smoke palls drifted through many urban areas at noon that reduced visibility to less than a block. The dirty, dark atmosphere caused traffic accidents, injuries, and even death. Doctors increasingly linked the drab, polluted air to depression and tuberculosis.

Indianapolis was no exception. The Indianapolis News reported on February 11, 1904 that “for a year or more, the smoke cloud has constantly been increasing until during the last two or three months, the city has taken a place among the smoke cities of the country and by some visitors is credited with being as dirty as Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, or St. Louis.” That summer, the News described “dense volumes of black soot and smoke” blowing through business and residential districts across the city. A journalist wrote “Eyes and lungs are filled and as for wearing clean linen any length of time, that is one of the impossibilities.” The journalist noted that the smoke damaged goods in downtown shops and observed “every article in them to be thickly dotted with soot.”

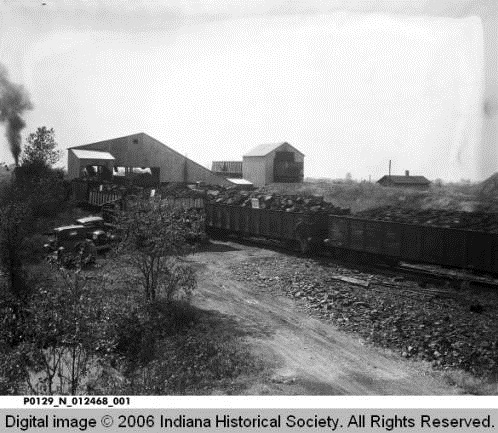

Despite these issues, fighting smoke pollution in Indiana would be hard. Coal is one of Indiana’s natural resources and became a mainstay of the Hoosier economy during the early 20th century. It was discovered along the Wabash River in 1736. Organized coal production began in the 1830s and after World War I, production exceeded 30 million tons. Furthermore, coal and the smoke it produced became a symbol for economic prosperity nationwide. Often, postcards and promotional imagery for cities featured pictures of smokestacks emitting billowing, black clouds of smoke across the urban landscape. A writer for the Indianapolis News in defense of coal wrote in 1906, “But if the coal smokes, let it smoke . . . Wherever there is smoke there is fire, and the flames that make coal smoke brighten the world of industry and bring comfort to the untold hundreds of thousands of toilers. Let it smoke. The clouds of smoke that ascend to heaven are the pennants of prosperity.”

Indiana produces bituminous coal, a soft coal that often creates a lot of smoke when burned. Many cities had begun to abate smoke pollution simply by requiring residents and industry to burn anthracite coal, a harder coal that burned cleaner. Since bituminous coal was a major source of wealth for Indiana, many Indianapolis residents and businessmen did not want to take this course of action, even though they did support cleaner air for the city.

One method to abate smoke, but still burn Indiana bituminous coal was to install automatic stoking devices in factories and homes. These devices distributed the coal in furnaces more evenly so it produced less smoke. In 1904, the American Brewing Company on Ohio Street downtown installed one of these devices. According to the Indianapolis News, this device allowed the company to burn just as much bituminous Indiana coal as it had last year, but produce far less smoke: the journalist described the company’s smokestacks as “practically smokeless.”

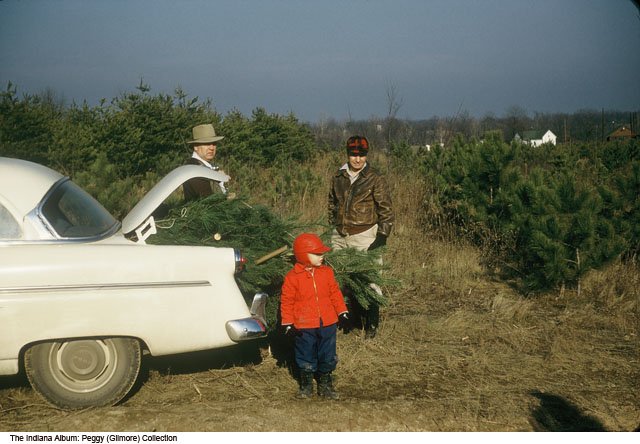

However, few businesses followed in the American Brewing Company’s footsteps. In 1910, Indianapolis women formed the Smoke Abatement Association operating under the slogan “Better and Cleaner Indianapolis” to try to get housewives and manufacturers to stop burning bituminous coal. These women became part of a nationwide movement of middle and upper class housewives practicing “Civic Motherhood” or “Municipal Housekeeping” that drew on women’s traditional roles as protectors of the home. These women reformers argued they could use their skills as household managers to improve the health of the communities their families lived in and thus began to participate in political discussions surrounding health, pollution, and sanitation, like air pollution.

The group first asked women to reduce smoke produced in their homes by installing smoke control devices. The group offered demonstrations for proper coal firing and issued reports on local residences and factories that issued a lot of smoke. In 1913, the group succeeded in getting a city ordinance passed which banned burning bituminous coal in a downtown district bordered by Maryland Street, East Street, New York Street, and Capitol Avenue. To honor Indiana’s coal production industry, bituminous coal could be burned if a smoke prevention device was installed. It was hoped this ordinance would create a clean, smoke free section of the city to improve health and help merchants preserve goods otherwise ruined by the sooty air.

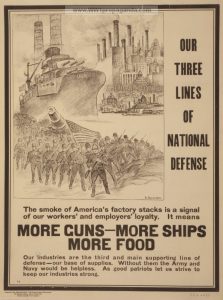

Though the Smoke Abatement Association remained active throughout the 1910s, US entry into World War I reverted smoke pollution’s image. Black and gray smoke churning out of smokestacks once again became symbolic of progress, this time in support of the war effort. Throughout the 1920s until the 1950s, air pollution remained regulated at the local level; state and federal governments largely remained aloof of the issue.

However, a more complex air pollution emerged in the 1940s that became a struggle for locals to solve on their own. In the summer of 1940, a thick eye-stinging, tear-producing, throat-irritating haze never before experienced enveloped Los Angeles. Though it eventually cleared, episodes continued as America entered World War II: the effects on health were so irritating, some Los Angelinos speculated it was a chemical attack from the Japanese. The problem persisted into 1943: various industries were suspected of causing the issue, but when they were shut down, the harmful air remained. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, this phenomenon, known increasingly as “smog,” afflicted almost every major urban area in the United States.

This was a complex type of pollution: growth in industry during World War II and the postwar era increased the amounts of emissions released into the air from factories as they burned oil and coal to create goods for the war effort, and later refrigerators, household appliances, and other consumer goods. During this time, the development of new chemicals, drugs, pesticides, food additives, and plastics also proliferated the consumer market. When manufactured, these products released a number of synthetic chemicals into the atmosphere that decomposed much more slowly than those emitted by older industries and remained hazardous longer. Lastly, the rise in population and expansion of the suburbs increased the use of automobiles. Cars blew out gasoline vapor that became a major ingredient in smog formation. All these combined emissions created a much more complex air pollution that was much harder to get rid of that would require cooperation from consumers, industry, and government regulation at all levels.

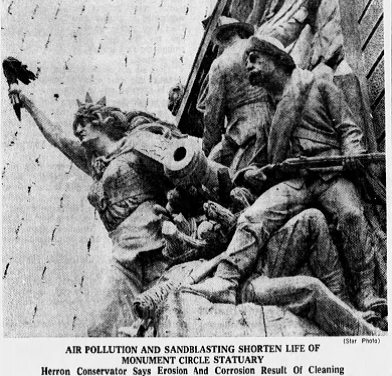

This type of pollution first appeared in Indianapolis in the mid-1940s, but did not become much of a chronic problem until the late 1960s. The pollution became so bad that it stained and eroded the limestone on the Soldiers and Sailors Monument downtown, as well as the façade of the Statehouse. It also became tied to increased rates of emphysema, lung cancer, and other serious diseases. Again, Hoosier women stepped up to try to improve the air in their neighborhoods, communities, and the state at large. They became part of a larger movement of women concerned with air pollution across the country and helped make it a national issue during the 1970s.

Many women fought air pollution through the League of Women Voters. League members traditionally conducted extensive research on political issues, conducted educational campaigns, and lobbied local, state and federal governments to make sure appropriate regulation was enacted. League of Women Voters members in Indianapolis, Richmond, and Seymour branches attended and testified at local air quality hearings, wrote to representatives urging more stringent air quality regulations, and sponsored programs and produced literature to teach the public about air pollution, current regulations, and what they could do to improve the solution. For example, these methods encouraged people to stop open burning of waste and carpool, bike, or walk to reduce automobile emissions.

Other women’s groups in the state took similar action. Housewives Effort for Local Progress, or HELP, a women’s group in Terre Haute dedicated to improving the city, took on air pollution as one of its major agendas. They lobbied local commissioners and educated the public on air pollution. The Richmond Women’s Club organized funds to purchase educational materials on air pollution to distribute to local students. Other women joined ecology groups, such as the Environmental Coalition of Metropolitan Indianapolis and fought for the passage of many regulations to control harmful gasses emitted by industry, such as Sulphur oxides. Chairwoman Elaine Fisher summarized the important role of the public in abating pollution: “Industry is pressuring . . . on one side. The only hope is for the public to give equal pressure on the other side.”

These women’s groups, and others across the nation, raised awareness of air pollution and made it a national issue. Most groups encouraged the federal government to get involved with air pollution. Since air pollution spreads across local and state boundaries, it made sense for increased federal oversight to control the issue. It is not a surprise that women’s fight against air pollution coincided with the passage of key federal environmental legislation, such as the Clean Air Act amendments of 1970, which gave federal officials authority over reducing air pollution throughout the nation and the power to set federal emissions states have to comply with. The Clean Air Act has produced purer air for all Americans: since 1970 its regulations reduced the levels of common pollutants, and thus prevented deaths from disease and cancer and decreased damage to plants, crops, and forests previously caused by air pollution. Thank you, Hoosier women.