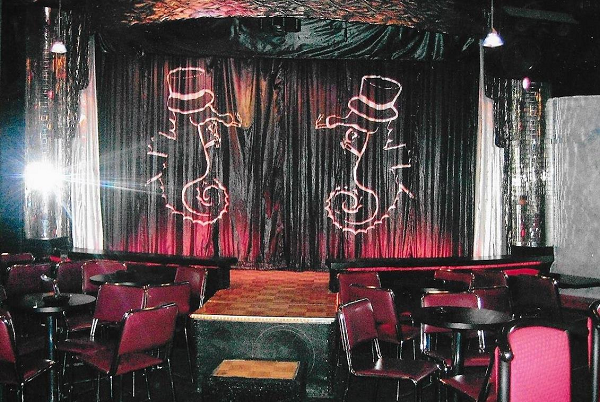

In 2015, Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend announced in a South Bend Tribune op-ed that he was gay, making him Indiana’s first openly gay mayor. Four decades before Buttigieg’s announcement, the city reportedly outlawed same-sex dancing. In 1974, Gloria Frankel and her gay club, The Seahorse Cabaret, withstood police harassment, challenged regulations against LGBT individuals, and endured a firebombing. In this post, we explore the fight for gay rights in the Michiana area and the intrepid woman who lead the charge.

According to Ben Wineland’s “Then and Now: The Origins and Development of the Gay Community in South Bend,” Frankel opened South Bend’s first gay club in the early 1970s. Its opening followed the famous Stonewall Riots of 1969, in which members of New York City’s LGBT bar community responded to a police raid with a series of violent protests. The riots immediately forwarded the gay liberation movement and the fight for LGBT rights in America. LGBT individuals in smaller cities capitalized on the momentum by opening bars that fostered gay communities and provided them with a relatively safe space for entertainment, dialogue, and activism.

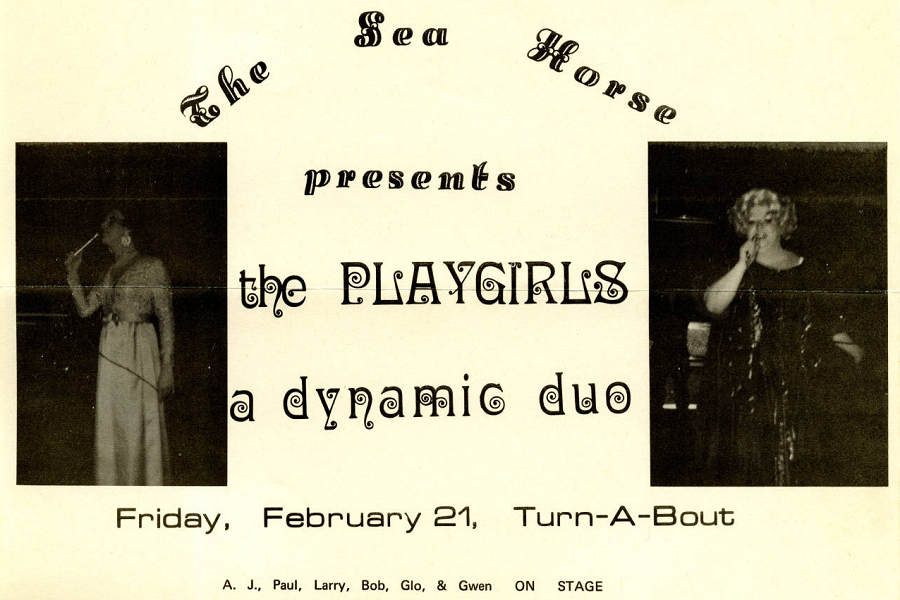

Frankel filled this role in South Bend with The Seahorse. She hosted shows and events, and distributed fliers for them, an act “which embodied the new kind of confidence and visibility that the Stonewall riots helped to create.” Also like those who frequented the raided Stonewall Inn, patrons of The Seahorse encountered an intimidating police presence, in which officers would “‘walk around and make people nervous. ‘Cause it was a gay bar'” (Wineland, 74). In 2005, Frankel recalled “I always wanted to open a bar where gay people openly socialized with each other. Back when I first opened the bar, people were ashamed of who they were and frightened of the severe consequences if they were found out. And at the time, being caught in a gay bar would land you in jail and lose you your job.” Wineland contended that The Seahorse was considered a threat by law enforcement because it “became more than just a hole in the wall, it looked to the opposition like hope; a hope for visibility, mainstream appeal, and a point of organization for the gay movement.”

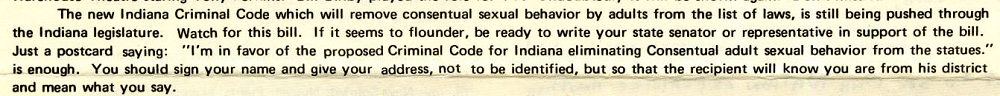

According to oral history interviews with Seahorse patrons-conducted by Katie Madonna Lee, producer of a forthcoming documentary about the club-a city ordinance prohibited same sex dancing until 1974. One interviewee recalled that if men were found dancing or being affectionate they would be arrested, escorted to the police station, and charged with a lewd act. According to these interviews and Frankel’s obituary, Gloria combated this by successfully challenging the City of South Bend to allow same sex dancing. More research should be undertaken regarding her reported legal battle. The Lambda Society* of Michiana was also concerned with laws discriminating against the gay community, urging newsletter readers in 1974 and 1975 to write their legislators.

In a May 1974 newsletter, the organization noted a desire to evolve from social objectives to those also involving advocacy. It noted that the organization was founded “because gay is more than sexual preference, and because gay can be more than just an alternative life style. Lambda has struggled through nine months offering little more than social functions as an alternative to the bars, baths, and bus station.”

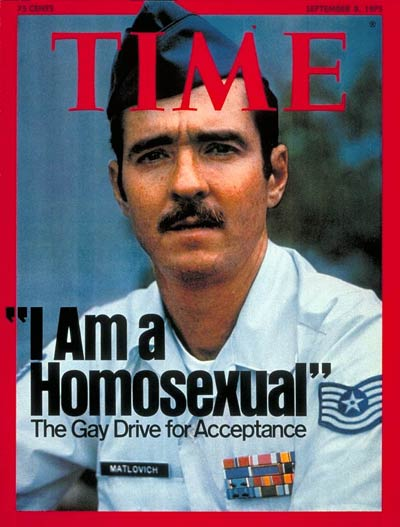

Newsletter articles about the 1974 Indiana Gay Awareness Conference in Bloomington, Indiana give a window into the origins of mobilized political action for Michiana’s LGBT community. One article noted that after discussing issues that gay individuals encountered with their families, police, landlords, and employers, the decision was made to “address the problem, which is not that we are criminals, but how to help others deal with their problems with homosexuality.” There was a panel discussion regarding “Gayness and the Law” and efforts were made to aid attorneys handling related cases. When discussing Indiana laws “hope was expressed that in the re-codification of our criminal code, consenting adult acts will be eliminated.” Notably,

mention was made that Illinois and Ohio have already removed consenting acts by adults from the criminal statues, that legislation is now pending in Michigan, and Kentucky is also considering some similar action, leaving Indiana ‘an island of persecution.’

The conference also held sessions about topics such as “Telling Your Parents,” “Professionals,” and “Racial Problems.” One newsletter author reflected candidly that “to say that this conference produced any dramatic changes or systems for dramatic changes, would be wrong.” However, it planted the seeds for unified efforts to change perspectives about homosexuals. The newsletter article noted that the conference showed “groups and individuals that there are others in our state willing to meet and try for change. As with all new associations, time and experience with each other and ourselves will cement the relationship into a working coalition for change.” The author concluded by stating “I learned more about others and my own attitutes [sic] towards homosexuals and straights. . . . we all joined hands in a circle, raised them high, singing We Shall Overcome – I was frightened – I was thrilled – I couldn’t have done that 24 hours earlier.” A 1975 newsletter illustrated some community support, printing an invitation from the Michiana Metropolitan Community Church, whose objective was to “better relationships amongst ourselves and within the community around us.”

Frankel too sought to forward the rights, identity, and well-being of the gay community. This may have been the motive behind someone stealing her car and setting it on fire in 1975. That year, a “Concerned Patron” wrote to the South Bend Tribune that the bar had to board its windows due to “rock and bottle throwing incidents” and that patrons only entered through the front door as a safety precaution. Nevertheless, Frankel’s Seahorse hosted Michiana Lambda Society events and successfully grew the local LGBT community, underscored by having to open The Seahorse II to accommodate an increase in patronage. Frankel also served as an unofficial mentor to others in South Bend who established gay bars, such as Jeannie’s Tavern and Vickie’s. She advised her “bar children” and had significant input regarding their businesses.

The Seahorse suffered a blow in 1982, when it was firebombed by an unidentified arsonist at 6:30 a.m. Residents who lived in apartments above the bar fled and one was hospitalized. Although firefighters contained the flames to the front of the building, it suffered approximately $90,000 worth of smoke damage.

Though devastating, the bombing demonstrated the solidarity of the South Bend’s LGBT community. According to code, the bar would be shut down if it could not get back to standards within ten days. Members of the community rallied to repair and clean it, shocking officials by getting the club back to code and reopening within the allotted time. They celebrated by hosting their annual anniversary party.

In the mid-1980s, the city used code enforcement to stymie Seahorse operations. This included denying the routine renewal of a liquor license and challenging the acquisition of a parking lot for customers. The Seahorse perceived these actions to be discriminatory, while the city insisted they were not.

Frankel continued to serve as a pillar of South Bend’s gay community when she led the local fight against HIV/AIDS in the early 1990s, funding AIDS ministries and making The Seahorse a cite of free HIV testing. Frankel stated “At that time gays were being terribly discriminated against, and many were afraid to go [to] the health department to get tested. So with the help of some friends, we cleaned up the back garage and turned it into a counseling center.”

The Seahorse continued to be foundational to South Bend’s LGBT community until 2007, when Frankel passed away. The club closed shortly thereafter and Jeannie’s Tavern became the home of Seahorse patrons and performers. However, Frankel’s pioneering efforts established South Bend’s enduring LGBT community.

*Lambda Legal Non-Profit Organization was founded in 1973 as “the nation’s first legal organization dedicated to achieving full equality for lesbian and gay people.”

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this blog, citing an oral history, suggested the profession of the arsonists. Also citing the same oral history, the blogger stated that Frankel erected a wall around the bar for protection. Former employees of the bar at the time of the arson have called into question the veracity of the oral history’s claims on these two points. In an effort for us to present an accurate account of the historical events, we have edited the blog accordingly.

Sources:

Conversation with Margaret Fosmoe, a South Bend Tribune reporter who graciously searched the newspaper’s archive for articles for this post.

Conversation with Katie Madonna Lee, producer of a forthcoming documentary about The Seahorse. Lee has conducted interviews and done extensive archival research about South Bend LGBTQ history.

Diane Frederick, “Homosexuality Laws Vary Widely,” Indianapolis News, August 22, 1975, 1, Indiana State Library, Clippings File-Homosexuality.

The South Bend Tribune, September 4, 1975, accessed Newspapers.com.

“The Seahorse,” The South Bend Tribune, September 11, 1975, accessed Newspapers.com.

Kathy Harsh, “Arson Suspected in Tavern Fire,” South Bend Tribune, November 26, 1982, Indiana State Library, microfilm.

St. Joseph County Public Library, Michiana Memory, LGBTQ Collection of the Civil Rights Heritage Center.

“Frankel Reaches 2 Milestones,” The South Bend Tribune, April 28, 2005, accessed Newspapers.com.

Ben Wineland, “Then and Now: The Origins and Development of the Gay Community in South Bend,” Indiana University South Bend Undergraduate Research Journal of History, vol. VI (2016): 69-79, accessed scholarworks.iu.edu.

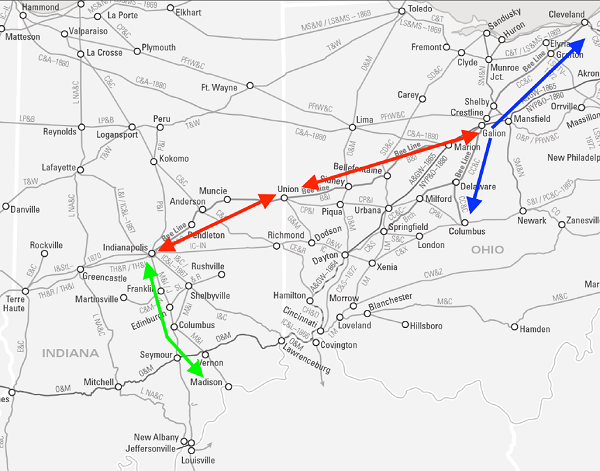

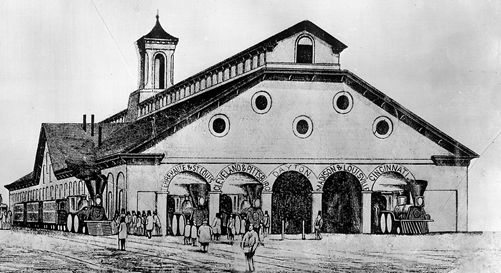

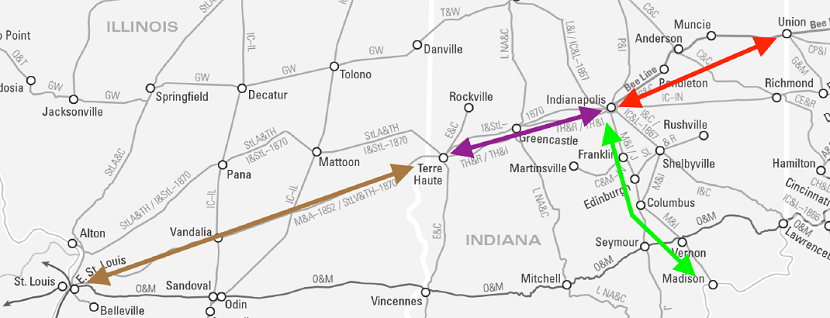

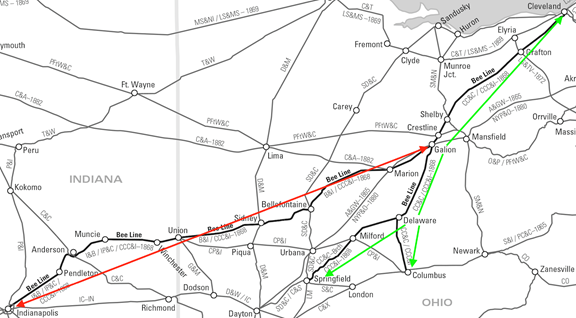

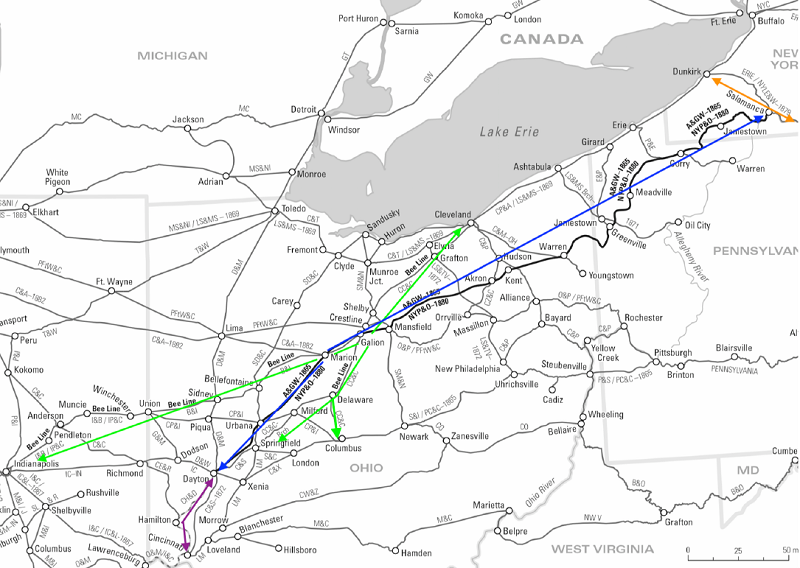

![Midwest Railroads Map, circa 1860, showing the Madison and Indianapolis [M&I], Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R], and component roads of the Bee Line: Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati [CC&C]; Bellefontaine and Indiana [B&I]; Indianapolis and Bellefontaine](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Midwest-Railroads-Map-c1860.png)

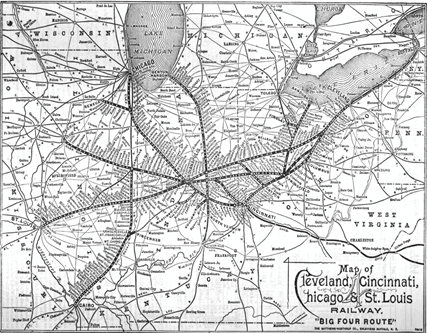

![Railroads west from Indiana, including the Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R], Ohio and Mississippi [O&M], Mississippi and Atlantic [M&A], and St. Louis, Alton and Terre Haute [StLA&TH]](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Railroads-West.png)

![image of The Madison and Indianapolis Railroad [M&I] and involved roads: the Peru and Indianapolis Railroad [P&I], extending north from Indianapolis, and the Mississippi and Atlantic Railroad [M&A], extending west to St. Louis. Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R]](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/MI.png)